The end of the Cold War, then, was undoubtedly a hugely

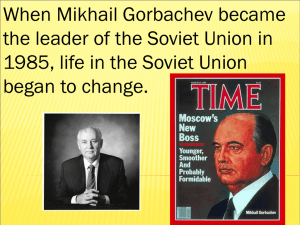

advertisement

Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 Florian Wastl f.wastl@lse.ac.uk IR502 13 February 2008 Draft – please do not quote or pass on. Process, not Factors: an Alternative Account of the End of the Cold War 1. Introduction There can be no doubt that the end of the Cold War was a highly complex event involving the interplay of many factors over the years. And yet, the five common approaches to explain the end of the Cold War which exist in the discipline largely fail to take account of this complexity. Instead, they (a) each posit just one discrete factor which they deem to have been, more than any other, responsible for the end of the Cold War; and for each approach, this is a different factor, depending on their assumptions about the nature of international politics. They also (b) rely on largely essentialist conceptions of social reality in which preformed entities are thought to determine the nature of social relations. As a result, each approach is able to account only for those factors which are consistent with ‘its’ preformed entities. Together (a) and (b) lead to a situation in which the dominant approaches in the discipline are unable to provide a unified account of the events which led to the end of the Cold War. A fuller account of the process is possible only through a ‘disaggregation’1 of events and explanations. In this paper, I will seek to apply an approach which focuses not on factors but on the particular interactions between them. It thereby enables us to analyse the process as a whole, not merely snapshots of its parts. The Cold War, then, ended not because of Wohlforth, William C., ‘Scholars, Policy Makers, and the End of the Cold War’, in ibid. (ed.), Witnesses to the End of the Cold War (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), p.283; see below for a full explication of this term. 1 1 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 any particular factor or factors per se but because of their timely and largely nonlinear interaction and confluence. 2. A Plethora of Factors The end of the Cold War was the biggest shift in international relations for at least a generation. It saw the end of a global, bipolar conflict between two socio-economic systems which had been pitted against each other for some 40 years, with enough fire power on each side to destroy the world many times over. Many were taken by surprise by the speed and the peaceful nature of this rapidly unfolding event—but most of all they were surprised that it happened at all. Asked in 1984, not many people— scholars of International Relations or statesmen—would have suspected the Cold War was about to end, much less that it would be over by 1990. In fact, the early 1980s had brought a significant rise in tensions between the two superpowers after a brief period of thaw in the 1970s. Yet, between March 1985 when Mikhail Gorbachev took office and October 1990 when Germany was reunified, the Cold War went from being the defining feature of the international system—permanent in the minds of many—to becoming no feature at all, irrelevant to the realities of a ‘new world order’2. In the space of only five and a half years, the world had witnessed the enactment of wideranging domestic reforms in the Soviet Union; the signing of numerous arms control treaties between the Soviet Union and the United States; the gradual dismantling of the Soviet socialist economy and of communist ideology among the Soviet leadership; the revocation of the Brezhnev Doctrine, shortly followed by the end of communism in Eastern Europe after an avalanche of largely peaceful revolutions; and Soviet ac- 2 Bush Sr., George, on the eve of Operation Desert Storm to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait, 16 January 1991. 2 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 ceptance of German reunification within NATO. The demise of the Soviet Union itself followed little over a year later. The question is why this rapid and unexpected change. Unfortunately, we are unlikely to be given any straight-forward answer. The end of the Cold War did not just consist of one single major event but it was made up of a sequence of many ‘smaller’ events and changes, and their interplay. It involved many actors and, despite the speed of change, it took years to unfold. This, but also the fact that no one had seen it coming right until the end, suggests that there must have been a whole plethora of possible reasons, factors, and causes—and combinations between them—that may have contributed to the ending of the Cold War. There are currently five dominant approaches in the discipline which seek to explain the end of the Cold War. If one is to believe their judgement, there are a maximum of five chief factors which caused the Cold War to end, a different one according to each approach. Taken together, these were (i) ‘new thinking’, (ii) Soviet terminal decline, (iii) Soviet domestic politics, i.e. the attempt to renew socialism from within, and the crucial influences on events by (iv) Mikhail Gorbachev and (v) Ronald Reagan. Yet, consider how many other possible factors may also have played a role in bringing the Cold War to an end. Consider, for example, the suggestion put forward by Vladislav Zubok (2005) that the Soviet Union was in fact materially much stronger vis-à-vis the United States in the 1980s than in the late 1940s, yet had lost much of the moral sense of purpose it had had shortly after World War II. 3 Zubok argues that, by the early 1980s, many in the Soviet elites and leadership began to question the rationale for opposing the United States, as it was becoming clear that the Soviet Union Zubok, Vladislav M., ‘Unwrapping an enigma: Soviet elites, Gorbachev and the end of the Cold War’, in Pons, Silvio and Federico Romero (eds.), Reinterpreting the End of the Cold War: Issues, interpretations, periodizations (London/New York: Frank Cass, 2005), pp.158-160 3 3 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 did not meet many of the expectations that had been vested in it, economic, social, or moral. “A growing number,” he writes, “looked towards the Western countries, not as enemies, but as objects of emulation and envy.”4 Zubok argues that Soviet elites, having lost their belief in the world-bettering mission of their state, were also losing their imperial will. And there is more. The 1975 Helsinki Final Act, according to Nick Bisley (2004), may have had a similar effect. It not only “provided a means with which people could measure Soviet action and find it wanting”,5 but more importantly, Bisley writes, by signing up to some key liberal principles of international relations, “Helsinki planted the first seed of normalisation among elites, dissidents and eventually the population as a whole.”6 It was the first acceptance by the Soviets of their normality as a state in the international system. Bisley argues that the Soviet drive towards normality, and its eventual completion, ultimately brought the Cold War to a close.7 Or consider the impact of ‘Eurocommunism’ on the increasing social-democratisation of the Soviet leadership and their reform agenda. Communists in Spain and France, but particularly those from the strong communist party in Italy, had been critical of Soviet-style communism for some time. Odd Arne Westad (2005) suggests that, later on, they may have come to serve as an inspiration for reformers within the CPSU, as Italian communists were strongly of the view that democratic politics in fact suited socialism best.8 Zubok, ‘Unwrapping an enigma’, pp.158-159; this is not the same as the decline argument which is focused on a disparity in material capabilities and not on disillusioned elites. 5 Bisley, Nick, The End of the Cold War and the Causes of Soviet Collapse (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), p.102 6 Bisley, End of the Cold War, p.102 7 Bisley, End of the Cold War, pp.76, 87, 93 8 Italian Communists regularly won about 30% of the Italian vote; Westad, Odd Arne, ‘Beginnings of the end: how the Cold War crumbled’, in Pons, Silvio and Federico Romero (eds.), Reinterpreting the End of the Cold War: Issues, interpretations, periodizations (London/New York: Frank Cass, 2005), pp.71-73; see also Lebow, Richard Ned and Janice Gross Stein, ‘Understanding the End of the Cold 4 4 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 Furthermore, there was Willy Brandt’s ‘Ostpolitik’ of the early 1970s which had opened more doors in the Soviets’ protective fence than many Eastern regimes had anticipated, and ultimately, more than they could bear. Westad writes that not only did West German engagement lower fears of a revanchist Germany in Eastern Europe, thereby lowering the Soviet grip on these countries as a communist bulwark against the German threat, but it also made Eastern European regimes more accountable in the eyes of their own people, and regimes were keen, but ultimately not very successful, to limit the contacts Ostpolitik had created.9 Not to mention the election of Polish Pope John Paul II in 1978. Agostino Giovagnoli (2005) argues that John Paul II’s election was a major cause for concern for the regimes of the Eastern bloc. It was not so much his anti-communism and emphasis on human rights, which had been shared by his three predecessors, that posed a problem for the USSR and other communist countries in eastern Europe. Rather, it was that Karol Wojtyla was of Slavish origin, came from Poland, spoke people’s language, and had lived under communism himself.10 Thus he was able, as Giovagnoli writes, to offer “an alternative to communism’s explanation of the needs of [eastern European] populations, an alternative that the communist regimes were ‘ideologically’ unable to defeat.”11 He spoke for many in the region when he emphasised long-standing continuities and conceived of Europe as a unitary whole. All this undermined the ideological hold of communism and made John Paul II dangerous to the regimes of the Soviet bloc—and it may ultimately have contributed to the end of the Cold War. War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, in Herrmann, Richard K. and Richard Ned Lebow (eds.), Ending the Cold War: Interpretations, Causation, and the Study of International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2004), pp.200, 205; and Lévesque, Jacques, ‘The Emancipation of Eastern Europe’, in Herrmann, Richard K. and Richard Ned Lebow (eds.), Ending the Cold War: Interpretations, Causation, and the Study of International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2004), pp.125-126 9 Westad, ‘Beginnings of the end’, pp.69-71 10 Giovagnoli, Agostino, ‘Karol Wojtyla and the end of the Cold War’, in Pons, Silvio and Federico Romero (eds.), Reinterpreting the End of the Cold War: Issues, interpretations, periodizations (London/New York: Frank Cass, 2005), pp.84, 87 11 Giovagnoli, ‘Karol Wojtyla’, p.88 5 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 And what of Soviet Third World engagements? The fostering of socialist regimes around the world, and the installation of new ones wherever possible, was long perceived to be an important part of the global contest between socialism and capitalism. Yet, as Westad argues, Soviet disenchantments in regard to their Third World commitments may have played a much greater part in effecting the foreign policy reorientation of the 1980s than previously believed.12 In the two years between the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in 1979 and non-intervention in Poland in 1981, an important shift may have taken place, as Soviet elites were becoming increasingly disillusioned with the state of affairs in socialist regimes around the world, and were beginning to count the cost of their involvements. This shift could have already set the path for years to come. “It is not surprising,” Westad finds, “that many who had first engineered, and then rejected, Soviet interventionism later re-emerged as reformers during the Gorbachev era.”13 Consider also the potentially important impact of the change in mutual threat perceptions on the easing of tensions during the latter years of the Cold War. Robert Jervis (1996) argues that the Cold War was in large part driven by the existence of conflicting social systems and the threat they posed to each other. As the Soviet leadership’s increasing social-democratisation and its disillusionment with socialism’s record was changing Soviet perceptions of the threat posed by capitalism and the West, so Gorbachev’s public repudiation of ideology radically changed the United States’ perception of the USSR—despite the continued existence of large arsenals of nuclear weapons on both sides.14 Indeed, Jervis writes “from what Secretary of State Shultz says, it appears that the United States was more impressed by the renunciation of ideology in Westad, ‘Beginnings of the end’, pp.76-77 Westad, ‘Beginnings of the end’, p.77 14 Jervis, Robert, ‘Perception, Misperception, and the End of the Cold War’, in Wohlforth, William C. (ed.), Witnesses to the End of the Cold War (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp.225-231 12 13 6 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 Gorbachev’s UN speech than by the concrete promise to reduce troop levels in Eastern Europe.”15 This reduction in mutual threat perceptions led to a change in the terms of engagement between the two sides. As did personal relations between the two groups of leaders. Fred I. Greenstein (1996) argues that the frequency of negotiations between the two sides in the period from 1985 to 1989 provided them with an important ‘safety net’ to deal with events or misunderstandings that might previously have led to a chilling in relations. Often leaders simply knew each other well enough to give one another the benefit of the doubt. “The great bulk of the change in superpower relations during the second term of the Reagan presidency,” writes Greenstein, therefore “took less tangible forms than arms control agreements and efforts to reduce force levels. In large part it consisted of transformations in mind-sets, perceptions, and expectations. Where suspicion and animosity had been, guarded trust and goodwill came to be.”16 And the list continues. Much is often made of Reagan’s hard-line policies which are said to have driven the Soviet Union beyond breaking point and out of business. Yet, his hard-line approach, according to Greenstein, may also have had a much more subtle, if not necessarily less effective, impact on the course of events which led to the end of the Cold War. Through his tough anti-communist stance, Greenstein argues, Reagan was uniquely placed to negotiate an end to the Cold War. His outspoken opposition to communism gave many the feeling that he was an extraordinarily safe pair of hands in his dealings with the Soviets. This made him all but invulnerable to rightwing attack for seeking an accommodation with the Soviet Union.17 And it was of Jervis, ‘Perception, Misperception, and the End of the Cold War’, pp.225-226 Greenstein, Fred I., ‘Ronald Reagan, Mikhail Gorbachev, and the End of the Cold War: What Difference Did They Make?’, in Wohlforth, William C. (ed.), Witnesses to the End of the Cold War (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp.200, 207 17 Greenstein, ‘Reagan, Gorbachev, and the End of the Cold War’, pp.215-216 15 16 7 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 some importance that he could engage with Gorbachev as freely as he did. According to Bisley, American “willingness to talk in reasonable and open terms was of crucial importance to Gorbachev and the changes he was trying to impose. […] The Americans helped give Gorbachev a very important platform by embracing him as a person to talk to, to take seriously and, belatedly to believe in.”18 Nor should one forget the more ‘accidental’ developments which took place during this period, and which may have contributed to ending the Cold War. Robert English (2005) argues that Chernobyl provided a push for domestic reform by exposing the corruption and inhumanity of the Stalinist command-administrative system, as it emerged that the Soviet leadership and, by extension their international counterparts, had been misled by hardliners from within the regime. Meanwhile, the outpouring of Western aid and goodwill strengthened internal support for Gorbachev’s foreign policy stance and sparked a renewed urgency on his part to try to break the deadlock in US-Soviet relations.19 In short, as Richard Ned Lebow and Janice Gross Stein (2004) write, “the cover-up of Chernobyl […] drove home the lessons of openness and international cooperation to Gorbachev and made it easier for him to implement restructuring.”20 A similar ‘accident’ was provided by young West German interloper Matthias Rust in May 1987 when he landed a small plane on Red Square. Archie Brown (2004) argues that Gorbachev used this as an opportunity to purge the military and replace defence minister Sergey Sokolov with Dmitriy Yazov who was more inclined towards Gorba- 18 Bisley, End of the Cold War, p.100 English, Robert, ‘Ideas and the end of the Cold War: rethinking intellectual political change’, in Pons, Silvio and Federico Romero (eds.), Reinterpreting the End of the Cold War: Issues, interpretations, periodizations (London/New York: Frank Cass, 2005), pp.128-129 20 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.207 19 8 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 chev and his policies than Sokolov.21 This ‘quiet coup’, in the words of Anatoly Dobrynin, 22 chairman of the CPSU’s International Department at the time, enabled Gorbachev to deflect powerful opposition to his plans for disarmament and other proposed changes. Rust’s flight to Red Square may, therefore, have been an important factor in facilitating those processes which eventually led to the end of the Cold War.23 Finally, we must not forget time and process as a potential factor. The end of the Cold War was a long, drawn-out process, not a set event, and conditions at the outset were very different from those further along in this process. Neither of the main protagonists had a clear idea of where they were headed, or where this interaction would take them, at the beginning of this process. It was only through the passage of time that particular windows of opportunity opened up and more specific—and far-reaching— goals became possible, and were formulated.24 As Lebow and Gross Stein write, “process is often given impetus by deliberate initiatives of various parties and stimulated and given momentum by outside events.”25 Over time, behaviour and outside events may have led to unintended consequences which ultimately led to the transformation of the system as a whole—an outcome which was thus ‘doubly’ unintended.26 In the end, therefore, we may need to see the end of the Cold War as a largely unintended consequence in which time and process had a major part to play. Brown, Archie, ‘Gorbachev and the End of the Cold War’, in Herrmann, Richard K. and Richard Ned Lebow (eds.), Ending the Cold War: Interpretations, Causation, and the Study of International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2004), p.44; Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a NonLinear Confluence’, pp.198, 207 22 Dobrynin, Anatoly, In Confidence: Moscow’s Ambassador to America’s Six Cold War Presidents (1962-1986) (New York: Random House, 1995), p626; quoted in Brown, ‘Gorbachev and the End of the Cold War’, p.44 23 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.207 24 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, pp.207, 212-214 25 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p. 207 26 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p. 214 21 9 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 A good example of this is provided by the case of German reunification within NATO. Clearly inconceivable even as things were beginning to spiral out of control in the autumn of 1989, it was not until events took a different turn following the fall of the Berlin Wall that things began to move in the direction of eventual reunification under NATO. It was only when East Germans began to demand economic and political unification, first in Leipzig in late November 1989 (‘Wir sind ein Volk’), then as they were leaving for West Germany in their tens of thousands each month demanding that the deutschmark come to them or they would go to it, and as the GDR was rapidly imploding, that quick reunification became almost inevitable.27 The Soviets were now faced with a dilemma: By the spring of 1990, the momentum for reunification was building fast, while the United States and West Germany were simultaneously pressing for a united Germany to remain inside NATO. Finally, as events had all but overtaken them, a deal was struck between the US, West Germany, and Gorbachev in the summer of 1990 in which it was agreed that the reunified Germany would remain a full member of NATO in exchange for Germany’s financing of the withdrawal of Soviet troops from East Germany. German reunification within NATO did almost certainly not feature on Gorbachev’s wish list, not in 1985, not when he announced the end of the Brezhnev Doctrine in March 1988,28 not even as the Berlin Wall was coming down in November 1989. Instead, it was brought about by a sequence of outside events, to which he may have given the initial impetus, but which had rapidly spiralled outside his control. 27 Rapid reunification was also made possible by some skilful politicking from Helmut Kohl, the West German chancellor, aided by the strong support given to him by George Bush. See Davis, James W. and William C. Wohlforth, ‘German Reunification’, in Herrmann, Richard K. and Richard Ned Lebow (eds.), Ending the Cold War: Interpretations, Causation, and the Study of International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2004), pp.132, 138; for a full account of events surrounding Germany reunification, see Davis and Wohlforth, ‘German Reunification’, pp.131-157 28 Before the Yugoslav Federal Assembly. 10 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 3. The Need for an Alternative Framework Surely, neither of these factors—and possibly many others—can be wholly discounted in any study which seeks to establish why the Cold War came to an end. All of them did in some way influence the course of events. Some may have been more, some less important than others; some may have provided crucial turning points;29 others may have gone almost unnoticed but provided decisive catalysts for other factors to come into play and crucially shape events; yet others may have been obvious underlying causes but in reality they required the existence of other factors to become causally ‘active’; and somehow all these factors interacted with each other, simultaneously and over time. To make matters worse, this plethora of factors existed across several levels. These are most crudely speaking, the international, domestic, and individual levels, but as we have seen from the discussion of the many possible factors above, in reality these were interspersed with, and dissected by, many more intermediate levels such as party, social, economic, transnational, intellectual, and ideological. The end of the Cold War was a hugely complex event. It should be clear that an event of such complexity cannot be captured by a simple, uni-directional correlation of cause and effect, and therefore, ultimately, by defining dependent and independent variables.30 Alas, however, that is largely the methodology pursued by the five dominant approaches to explain the end of the Cold War. They do, for the most part, stipulate that one variable, above all others, fundamentally accounts for the variation that was the end of the Cold War. Other factors are allowed merely to have influenced the 29 For a study of turning points during the end of the Cold War, see Herrmann, Richard K. and Richard Ned Lebow (eds.), Ending the Cold War: Interpretations, Causation, and the Study of International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2004) 30 Jervis, Robert, ‘Systems and Interactions Effects’, in Snyder, Jack and ibid. (eds.), Coping with Complexity (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1993), pp.26, 41; quoted in Wohlforth, ‘Scholars, Policy Makers, and the End of the Cold War’, p.275 11 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 timing, nature, and implications of the event but are not deemed to have been responsible for the fact that the variation itself took place, i.e. that the Cold War came to an end. This has led to five largely incompatible stories of the end of the Cold War, each based on a different set of ontological assumptions, and each analysing the available evidence differently as a result. However, the fact that such a complex event as the end of the Cold War cannot be adequately accounted for by simple correlative approaches is not wholly lost on the literature. Take, for example, William C. Wohlforth (1996), normally a supporter of the ‘Soviet terminal decline’ thesis. “We can and should,” he writes, “show the causal importance of individuals, perceptions, ideas, domestic constraints, and many other factors. […] Any explanation of this event will feature many causes operating at many levels. […] One could draw lines connecting all these factors, but in all cases the causal arrows point in both directions.”31 This is mirrored by Richard K. Herrmann (2004) who seeks “to promote a broader search for new evidence and more thoughtful and complex causal explanations.”32 Finally, Lebow and Gross Stein make a similar point when they call for “conceptual tools that bridge levels of analysis and permit a more rigorous framing of the problem of multiple causation.”33 Yet, despite these calls to move away from simple correlations of cause and effect with their propensity to produce conflicting accounts, and towards a ‘more comprehensive explanation’34 of the ‘process as a whole’35, no such unified analysis of the Wohlforth, William C., ‘The Search for Causes to the End of the Cold War’, in ibid. (ed.), Witnesses to the End of the Cold War (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp.198, 195; Wohlforth, ‘Scholars, Policy Makers, and the End of the Cold War’, p.275 32 Herrmann, Richard K., ‘Learning from the End of the Cold War’, in ibid. and Richard Ned Lebow (eds.), Ending the Cold War: Interpretations, Causation, and the Study of International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2004), p.225 33 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.196 34 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.191 35 Wohlforth, ‘Scholars, Policy Makers, and the End of the Cold War’, p.283; see also Checkel, Jeffrey T., ‘Tracing Causal Mechanisms’, International Studies Review 8(2) (2006), pp. 362-370 31 12 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 end of the Cold War has so far been provided. Even Herrmann and Lebow (2004), from whose edited volume some of the previous quotations are taken, divide the process of the end of the Cold War up into five distinct turning points.36 Herrmann claims that “by unpacking the interpretative task into smaller endeavours for which we could acquire new empirical information, we can determine whether particular explanations hold in one turning point as an exception or as a general rule.”37 In the same wake, Wohlforth speaks of the need for the event to be ‘disaggregated’, and that “different generalisations […] must be applied to its different parts.”38 Laudable therefore as their calls for a more complex and comprehensive explanation undoubtedly are, this sort of approach is unlikely to provide it. Rather, it leads to a focus on a series of separate events or, as in Herrmann and Lebow’s edited volume, on different turning points, with a different cocktail of factors identified as being responsible for each of them.39 What remains absent is an analysis of the process as a whole. I have argued previously (not included in this paper) that one reason why conventional approaches find it so hard to provide more comprehensive accounts of complex events like the end of the Cold War is because of an essentialist ontology at the heart of their analyses. By stipulating the existence of a number of preformed entities between which all social relations are supposed to take place, I have argued, they cannot account for factors that are inconsistent with these preformed entities or the social relations as they have been defined by them—at least not without making previously 36 Herrmann and Lebow define turning points as (1) changes of significant magnitude and (2) changes that are difficult to undo. The main turning points during the end of the Cold War were in their view: the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev, Soviet withdrawal from regional conflicts, arms control, the liberation of Eastern Europe, and the reunification of Germany. For more see: Herrmann, Richard K. and Richard Ned Lebow, ‘What Was the Cold War? When Did it End?’, in ibid. (eds.), Ending the Cold War: Interpretations, Causation, and the Study of International Relations (New York: Palgrave, 2004), pp.1-27, particularly pp.7-14 37 Herrmann, ‘Learning from the End of the Cold War’, p.226 38 Wohlforth, ‘Scholars, Policy Makers, and the End of the Cold War’, p.283 39 For a summary of the factors put forward by the different authors for each turning point in the edited volume by Herrmann and Lebow, see Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, pp.197-201 13 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 consistent factors newly inconsistent.40 To many, therefore, ‘disaggregation’ may seem the only feasible way of overcoming the constraints of the need for ontological consistency, and thereby, of providing a fuller explanation of complex events. The best we can hope for, writes Wohlforth, is that “many of the theories that seem to be competing may in fact be complementary, explaining different pieces of the puzzle.”41 Similarly—and despite their expressed aim to go “beyond an ad hoc historical narrative that draws together different explanations,”42—Lebow and Gross Stein argue that “scholars who work on questions with complex causes need to establish levels of indeterminacy and use them to assess the relative merit of competing explanations.”43 Neither is the comprehensive account of the process as a whole that both of them call for elsewhere. Instead, it is an approach punctured by numerous causal ruptures, or gaps, where one analysis ends—complete with its own logic and main factors—and another one begins. Ultimately, Wohlforth admits that complex events like the end of the Cold War may simply ‘defy causal analysis’.44 4. An Alternative Conception of the End of the Cold War In what follows, I will seek to dispel the notion that accounting for complex events like the end of the Cold War requires a ‘disaggregation’ of events (and explanations), This is why the discipline’s five dominant approaches to explain the end of the Cold War fail to deliver a more unified picture of the end of the Cold War. Essentialist ontologies prevent them from moving much beyond a certain set of relations (and factors) as ‘regulated’ by the nature of the entities which they regard as preformed. 41 Wohlforth, ‘Scholars, Policy Makers, and the End of the Cold War’, p.283; for a similar attempt to make competing approaches complementary through ‘disaggregation’, compare also Wendt, Alexander, ‘On Constitution and Causation in International Relations’, in Tim Dunne, Michael Cox and Ken Booth (eds.), The Eighty Years’ Crisis: International Relations 1919-1999 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp.103-112; Wendt, ‘Bridging the theory/meta-theory gap in international relations’, Review of International Studies, 17(4) (1991), pp.383-392; and Carlsnaes, Walter, ‘In Lieu of a Conclusion: Compatibility and the Agency-Structure Issue in Foreign Policy Analysis’, in ibid. and Steve Smith (eds.), European Foreign Policy: EC and Changing Perspectives in Europe (London: Sage Publications, 1994), pp.283-284 42 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.196 43 Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.191 (orig. emphasis) 44 Wohlforth, ‘Scholars, Policy Makers, and the End of the Cold War’, p.275 40 14 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 or that it may even defy the possibility of causal analysis altogether. I will show that it is neither necessary nor desirable to divide the end of the Cold War up into more digestible pieces, be it to enable us to paint a picture of the overall event by accounting for each individual event separately (Wohlforth), or to find out which explanation is the best overall by creating levels of indeterminacy across different individual events (Herrmann, Lebow and Gross Stein). Let us begin with the five dominant approaches which seek to explain the end of the Cold War. Each of them stipulates that one factor, above all others, was responsible for bringing the Cold War to an end. Yet, this is a different factor in each case so that there can be no final agreement among the different approaches why the Cold War ended. It was either ‘new thinking’ which lay at the heart of the end of the Cold War, or Soviet terminal decline, or domestic politics within the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc, or the actions and personality of Mikhail Gorbachev, or the tough policies of Ronald Reagan. Which of these one is most likely to subscribe to is determined by where one stands in one’s view of the nature of international politics. This is unlikely to give us an accurate picture of the highly complex and intricate nature of the end of the Cold War, made up as it was of a sequence of many ‘smaller’ events and changes, and their interplay, drawn out over several years, and involving many actors on both sides. It is just not very probable that the Cold War came to an end because of the presence, at the outset, of only one main factor, and it is nonsensical to any outsider that there should be five competing explanations for the same event. Wohlforth argues, of course, that they may not be in competition with each other but that different theories may just be best placed to explain different pieces of the process as a whole. This ‘disaggregation’ of events and explanations is undoubtedly a step forward. It enables us to take account of more than just one main factor, and thus, 15 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 to look at events beyond only those explained by that factor. Realists may now not just look at the Soviet Union’s material decline as a factor for why the Cold War came to an end, but also at the importance of ‘new thinking‘ and Gorbachev’s personality at other stages of the process. However, what this does not do is to overcome the essentialist propositions of the different approaches at the start. As consistency is, therefore, to be maintained with the nature of the entities at the bottom of each approach (i.e. logics of consequence vs. appropriateness; the international is more important than the domestic, etc.), there is only so far that any one explanation can reach before another has to take over, without any real linkage between them. Consider the following example: In accordance with this approach, we could argue that its material decline vis-à-vis the United States made it impossible for the Soviet Union to continue the standoff but it took the ideas of a new generation within the Soviet leadership, and the bold leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev, to face up to this reality and act upon it. However, does this really tell us how and why these three factors interacted with each other, or even if they did? All we can say for certain is that it seems logical, ex post facto, that they might have done. What we do in this approach, then, is just a papering-together of different factors, a patchwork, without any real thought to, or explanation of, how they may be connected to each other, or what other dynamics their connection, and that of others, may have facilitated. Such an approach fails to take account of nonlinearity, dynamic confluences, causal mechanisms, and the importance of process—and, thus, the causal linkage between different factors. Therefore, and most damaging of all, it cannot account for ‘real’ causation because it merely points to the existence of a number of different factors. Yet, as Lebow and Gross Stein rightly point out, the existence of “underlying causes do[es] nothing more than to create 16 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 the possibility of change.”45 What is missing is an account of how that change actually took place. The real question, then, is: how is that possibility of change actualised, or made effectual? What did really cause the Cold War to end? To answer this question, as indicated in the previous section, we must give a comprehensive account, not of the factors, but of the process as a whole that led to the end of the Cold War. It is important to recognise that it was neither ‘new thinking’, Soviet terminal decline, domestic politics, Gorbachev, or Reagan—nor any of the many other possible factors listed above—that were responsible for ending the Cold War, either individually or collectively, but it was the way in which the interactions between them created the conditions for the Cold War to end. As we will see, only such an approach can truly supersede the divisions between the different factors themselves, as well as give an account, however incomplete, of what really caused the Cold War to end. 4.1. Relations before Factors Factors which may have led to the end of the Cold War are usually presented as possessing fixed ‘factoral cores’ which determine their ‘factor-ness’ by giving them a particular causal essence. ‘New thinking’, for instance, is thought to have been a set of ideas which had developed among parts of the Soviet intelligentsia in the 1960s and 1970s, partly independently and partly through transnational exchanges with Western liberal internationalists. It entailed a strong commitment to the humanising and opening of the Soviet Union, and was rooted in beliefs of the one-ness of humanity, universal human rights, and common security. ‘New thinking’ reached the echelons of power with the election of a Secretary General who was open to its appeal, Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.214 (orig. emphasis); the full quotation reads: “Our study of the Cold War suggests the broader conclusion that underlying causes, no matter how numerous or powerful, rarely make an outcome inevitable, or even highly probable. Their effects may depend on fortuitous coincidences in timing of multiple causal chains, the independent actions of people, even on accidents unrelated to any underlying cause. The Cold War case suggests that system transformations—and many other kinds of international events—are unpredictable because their “underlying causes do nothing more than to create the possibility of change.” 45 17 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 and its policy impact was aided by the extraordinary authority invested in the Secretary General and the highly authoritarian, top-down structure of the Soviet political system.46 A similarly fixed definition exists of the ‘Soviet terminal decline’ factor. A stagnant economy, increasingly less able to support the mighty military apparatus, is said to have thrown the Soviet Union into material decline in the early 1980s. Following this, it was the subsequent change in the balance of power between the two superpowers, and the realisation amongst Soviet elites that reduced capabilities would make it impossible to continue competing with the United States on a par, which compelled Gorbachev towards an accommodating strategy vis-à-vis the United States.47 More factors could be mentioned to show that they have been conceived in a similar way. Yet, none of these factors, neither those just mentioned nor any others which may have contributed to ending the Cold War, can be seen in this ideal-type way. We cannot stipulate a factor and ascribe to it, by virtue of its internal ‘factoral core’, a particular causal essence for the process which led to the end of the Cold War, be this, in the case of ‘new thinking’, the emphasis on openness and the one-ness of humanity in Soviet policy, or ‘tipping the balance of power’ in the case of Soviet decline. Instead, their causal essence was derived only from the constant interaction in which they were embedded. In other words, they became what they were, not through any inner attribute of themselves, but only through their relations with other elements in the on- See English, Robert D., ‘Sources, Methods, and Competing Perspectives on the End of the Cold War’, Diplomatic History, 21(2) (Spring 1997), pp.283-294, esp. p.284; and Risse-Kappen, Thomas, ‘Ideas Do Not Float Freely: Transnational Coalitions, Domestic Structures, and the End of the Cold War’, in Lebow, Richard Ned and ibid. (eds.), International Relations Theory and the End of the Cold War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), pp.187-222, esp. p.188; and Checkel, Jeffrey T., Ideas and International Political Change: Soviet/Russian Behavior and the End of the Cold War (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1997); see also Chapter Three, pp.??-?? 47 See Wohlforth, William C., ‘Realism and the End of the Cold War’, International Security, 19(3), (Winter 1994-1995), pp.91-129; see also Chapter Three, pp.??-?? 46 18 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 going flow of events.48 Instead of having its causal essence in ‘tipping the balance of power’, then, Soviet decline may possibly have influenced the course of events through its impact on Gorbachev’s, and others’, vision for socialism. Believing socialism was there for the betterment of the human condition, it may have troubled Gorbachev that the Soviet economy could produce the most sophisticated weapons systems but was increasingly less able to provide an ample supply of some of life’s most basic necessities. Dissatisfied and disillusioned as Gorbachev may have been with the system as it was, his disgruntlement would have made little impact on policy, had it not been for the high measure of flexibility in his thinking and personality which allowed him to contemplate a break with one of the most central, and oldest, doctrines of Soviet existence: that of having to oppose the capitalist West whatever the cost. But even his own readiness to break with this important doctrine would not have been sufficient to affect policy if Gorbachev had not had the power to persuade the politburo that, to put socialism in a position in which it would be better able to fulfil its promise, the Soviet Union would benefit from a partial normalisation of its relations with the United States. In this possible scenario, which only retraces the first steps on the long road which eventually led to the Cold War’s end, we see the seamless interaction of at least four of the five ‘standard’ factors, as well as some of the additional ones listed at the beginning of this paper. We see the interaction of material decline, disappointment of the expectations vested in socialism, ‘new thinking’, Gorbachev’s personality, loss of the imperial will, domestic politics, the authoritarian nature of the Soviet political system, and the drive towards a normalisation of the Soviet Union. However, neither of For an account of ‘relationalism’, see Jackson, Patrick T. and Daniel H. Nexon, ‘Relations before States: Substance, Process and the Study of World Politics’, European Journal of International Relations, 5(3) (1999), pp.291-332; and Emirbayer, Mustafa, ‘Manifesto for a Relational Sociology’, The American Journal of Sociology, 103(2) (September 1997), pp.281-317; also see Chapter Four, pp.??-?? 48 19 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 these factors was given a causal essence in and of themselves. Instead, this essence derived only from the factors’ contextuality, that is, their relations with other factors. This does not yet, however, tell us anything about ‘real’ causation. Nor does it present a significant departure from the patchwork approach which I criticised above for merely papering together a number of different, plausible factors into any sort of explanation, without a view to how those factors were actually connected. Yet, recognising that factors do not possess fixed causal essences in and of themselves, but that they are fluid constellations which are given their causal essences only by virtue of their place in the relations with other factors, is nonetheless an important cognitive step. As Patrick T. Jackson and Daniel H. Nexon (1999) note: “If the world is understood to be composed of processes and relations, then we cannot divide the world into discrete variables.”49 It is, therefore, the precondition for any account which seeks to focus on process rather than on individual events and factors. If we did not understand the world as essentially relational and, conversely, we were to insist on the continued conception of factors as self-propelling entities with fixed causal essences, we would remain locked in the old need for consistency between different factors on the one hand, and the sort of events we would be able to account for on the other. The only way to provide a fuller explanation of complex events would be through a ‘disaggregation’ of events and explanations, as suggested by Wohlforth above, along with the ensuing patchwork approach and its inability to account for ‘real’ causation. While not a significant departure from this patchwork approach at this stage, the recognition that factors are entirely embedded in process and relation without any internal ‘core’ thus forms the precondition for more. 4.2 Explaining Change 49 Jackson and Nexon, ‘Relations before States’, p.306 20 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 As a first thing, such an approach allows us to account for complex change. An approach which puts relations and process before static factors can explain how a change in conditions may lead to emerging properties that may lead to further changes along the same process, and thus to outcomes which were unthinkable at the outset. In other words, so long as we do not contend that any particular factors are responsible, individually or collectively, for a change in conditions, but instead the relations between them, we can account for emerging properties and are thus able to provide a dynamic and endogenous account of change—in which change leads to more change—rather than merely taking ‘snapshots of dynamic statics’.50 It allows us, writes Mustafa Emirbayer (1997), “to avoid […] ad hoc reasoning and to develop causal explanations more self-consciously within a unitary frame of reference.”51 In this way, then, we can account for the emergence of new properties which were crucial in creating the conditions that brought the Cold War to an end. Consider the following example: When Gorbachev renounced the Brezhnev Doctrine and encouraged other communist countries in Eastern Europe to adopt similar reforms as those he had begun in the Soviet Union, he may have done so fully expecting that this would lead to a strengthening of socialism in the region. It would put socialism in those countries, so the possible reasoning, in a position to fully live up to its promise, and it would thus gain added legitimacy and economic prowess. Of course, this may well have happened, only had it not been for the particular interaction between Gorbachev’s joint message to reform, and to do so independently from Moscow, and a number of other factors present in the region, such as Western ‘benign power’, numerous lines of contacts with the West, the end of the perceived German threat, and a strong residue nationalism. These had been largely dormant and invisible as underly50 51 Jackson and Nexon, ‘Relations before States’, pp.303, 308 Emirbayer, ‘Manifesto for a Relational Sociology’, pp.311-12 21 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 ing factors until Gorbachev renounced the use of force to prop up the communist regimes of Eastern Europe. Their interaction with the implication of Gorbachev’s announcement created an important emerging property: the more or less complete loss of Soviet control over processes in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev had not intended it this way. He had surely expected to retain some influence over developments, if mostly of an ideological nature. Expected or not, however, conditions had changed dramatically and in such a way which led to further dramatic changes—unthinkable at the outset. As Eastern European countries were quickly looking West, what began as an encouragement to reform turned into a domino effect that was truly worthy of the name.52 Another example of this is provided by the change in mutual threat perceptions between the two superpowers. Here, again, a change in the underlying conditions created emerging properties which helped to move things beyond the realm of what had previously been conceivable. The change in the Soviet leadership’s mindset regarding the threat posed by capitalism and the West and, as that process continued, Gorbachev’s subsequent renouncement of ideology fundamentally changed Reagan’s perception of the Soviet Union.53 It led him to make his famous statement in which he, in turn, renounced his earlier pronouncement that the Soviet Union was an ‘evil empire’. Reagan’s suggestion that his earlier remark had been from ‘another era’ was indicative of the changed relationship between the two countries which made an end to the decades-long conflict between them possible. In some ways, it was only the emerging properties of a certain amount of normalisation in the relations between the two which eventually produced the possibility of almost complete normalisation. Compare Koslowski, Rey and Friedrich V. Kratochwil, ‘Understanding Change in International Politics: The Soviet Empire’s Demise and the International System’, in Richard Ned Lebow and Thomas Risse-Kappen (eds.), International Relations Theory and the End of the Cold War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), pp.127-165 53 Compare Jervis, ‘Perception, Misperception, and the End of the Cold War’, pp.225-231 52 22 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 Similarly, the much improved relations between the two groups of leaders may have done much to create possibilities previously unheard of. Through the frequency of negotiations between the two sides, leaders began to emerge from being mere representatives of their respective systems to being ‘real’ people. As Greenstein puts it so aptly: “It is possible to envisage mutually assured destruction as a means of deterring an impersonal representative of an alien political system; it is repugnant to rely upon such a mechanism when that individual is a genuine friend.”54 Again, a change in conditions, in this case in the personal relations between the teams of negotiators at the top, may have enabled them to do things previously unimaginable as the emerging properties of trust and goodwill came to replace hostility and suspicion. 4.3. ‘Real’ Causation Finally, an approach which puts process before factors also allows us to supersede the patchwork approach which merely slips factors together without accounting for how they were actually connected. A focus on process means that we cannot meaningfully speak of any single factors’ necessary versus sufficient conditions for the achievement of a particular outcome. This is because it is not particular factors which are either necessary or sufficient, or both, but only the process as a whole which is either sufficient (the Cold War ends) or not (it continues).55 To reflect this, one way of conceptualising causation is through the so-called ‘INUS-condition’ put forward by J.L. Mackie (1976).56 According to this condition, writes Heikki Patomäki (2002), “cause is an Insufficient but Non-redundant element of a complex that is itself Unnecessary but Greenstein, ‘Reagan, Gorbachev, and the End of the Cold War’, p.210; see pp.199-219 for more detail. 55 Jackson and Nexon, ‘Relations before States’, p.307 56 Mackie, J.L., ‘Causes and Conditions’, in M. Brand (ed.), The Nature of Causation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976) 54 23 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 Sufficient for the production of a result.”57 Let us consider the following illustration to see what this might mean. In this example, Mackie pictures a group of experts who are investigating the outcome of a house fire and conclude that it was caused by an electrical short circuit. He writes: Clearly the experts are not saying that the short circuit was a necessary condition for this house’s catching fire at this time; they know perfectly well that a short-circuit somewhere else, or the overturning of a lighted oil stove, or any number of others things might, if it had occurred, have set the house on fire. Equally, they are not saying that the short-circuit was a sufficient condition for this house’s catching fire; for if the short-circuit had occurred, but there had been no inflammable material nearby, the fire would not have broken out, and even given both the shortcircuit and the inflammable material, the fire would not have occurred if, say, there had been an efficient automatic sprinkler at just the right spot.58 What facilitated this particular outcome, therefore, was not any one particular factor, or factors. Each factor was in and of itself insufficient, albeit non-redundant. Instead, the particular constellation of the different factors altogether, that is, the complex (or process) as a whole—although unnecessary—became sufficient to produce the fire. This means that only the process as a whole was causally effective for the fire to occur. However, if it is only the particular constellation of all factors together that is capable of producing a result, not any one of them individually, or together collectively, 57 Patomäki, Heikki, After international relations: Critical realism and the (re)construction of world politics (London: Routledge, 2002), p.76 (orig. emphasis) 58 Mackie, ‘Causes and Conditions’, p.308 24 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 then the process is necessarily nonlinear. Actual change, then, depends on any number of the following: the particular timing and location of factors (i.e. their spatiotemporal context), outside catalysts or ‘accidents’, and the inadvertent confluence of unrelated causal chains.59 Consider the example of the fire: Had the short-circuit occurred elsewhere, without any inflammable material nearly, the sparks flying from it would have simply died away; equally, if someone had been home to spot the fire, it could have been put out before reaching any sort of destructive force; had there been no shortcircuit, the inflammable material nearby the electrical appliance which produced the short-circuit would not have caught fire; and had the electrical appliance which caused the short-circuit not malfunctioned and the inflammable material not been inflammable, nothing would have happened at all. As the case was, however, the shortcircuit happened, there was inflammable material nearby at the time of the shortcircuit, no one was home to detect the fire, and no effective sprinkler system had been installed. Everything, therefore, was in place, at the right time, for the complex to become causally effective. Now consider some of the events which led to the end of the Cold War. Clearly, the unexpected events of Chernobyl and Matthias Rust’s flight to Red Square each provided important catalysts for the advancement of Gorbachev’s reform agenda. He used both to consolidate his own position as well as that of his reforms by moving some potentially powerful opposition to his policies out of the way. Gorbachev may have encountered both stronger and earlier opposition, had it not been for the opportunities provided by these catalysts. While their importance for the end of the Cold Lebow, Richard Ned, ‘Contingency, Catalysts, and International System Change’, Political Science Quarterly, 115(4) (Winter 2000-1), pp.591-616; see also Chapter Four, pp.??-?? 59 25 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 War may be disputed, these ‘accidents’ nonetheless formed part of the overall process that led to its resolution.60 Of more interest, however, are those instances in which different causal chains met to significantly affect the course of events. The following provides a good example of this. Whatever the importance of economic stagnation in terms of the Soviet Union’s international posture, it crucially coincided with the deaths, in short succession, of some important members of the Brezhnev generation and the simultaneous comingof-age of ‘new thinking’. This confluence of factors from these three separate causal chains, made possible by their fortuitous timing, provided an important catalyst as it led to a reaction to the economic crisis quite unlike that which one would have come to expect from the dogmatic Brezhnev generation.61 Instead of the entrenchment we would have been likely to see from previous generations, it led to a fundamental rethink of socialism internally, and retrenchment internationally. A similar confluence was provided by the combination of Gorbachev as a representative of ‘new thinking’, his particular personality, and his strong leadership.62 Gorbachev’s election as General Secretary provided an important window of opportunity for ‘new thinking’ to find some role in future Soviet policy. His personality and leadership ensured that it would be right at the centre of policy throughout his term in office. If it had not been for the interaction of all three—new thinker, personality, leadership—‘new thinking’ would have been unlikely to be given the same prominence or momentum, both in terms of its political implementation and intellectual develop- See English, Robert, ‘Ideas and the end of the Cold War’, pp.128-129; Lebow and Gross Stein, ‘End of the Cold War as a Non-Linear Confluence’, p.207; and Brown, ‘Gorbachev and the End of the Cold War’, p.44 61 See Brown, ‘Gorbachev and the End of the Cold War’, pp.38, 54 62 See Brown, ‘Gorbachev and the End of the Cold War’, pp.38, 42; and Greenstein, ‘Reagan, Gorbachev, and the End of the Cold War’, p.211 60 26 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 ment. Both were crucial in driving Soviet policy to ever new horizons in its efforts to normalise relations with the United States. Or consider the important confluence between Soviet efforts to reduce tensions between the two superpowers and the presence of a US president who, by way of his tough anti-communist stance and rhetoric, was all but invulnerable to right-wing attack for doing deals with the Soviet Union. It is difficult to imagine the same amount of change taking place if the two had not occurred simultaneously. As Greenstein writes, Reagan “provided a permissive climate in which Gorbachev could continue his domestic and international initiatives.”63 A more muted American response, from a president less able or willing to engage seriously with the Soviets, may quickly have led to a significant slowing in Gorbachev’s policies and the reform process may have lost most of its momentum.64 Again, therefore, two separate chains of causation came together, at the right time, to produce the conditions for the rapid change which ensued. Yet, this was not the only important confluence produced by the simultaneous incumbency of Reagan and Gorbachev. Both leaders also shared a profound, and instinctive, dislike for nuclear weapons. As early as March 1983, Reagan was quoted as saying that it was ‘unthinkable’ to have these missiles forever pointed at one another.65 Both leaders were intent, therefore, on reducing the number of these weapons and their prominence in superpower relations.66 The subsequent reduction in nuclear arma- Greenstein, ‘Reagan, Gorbachev, and the End of the Cold War’, p.214 As Greenstein writes: “A less forthcoming president might well have created a siege mentality on the part of the Soviet leadership and in so doing discouraged Gorbachev and his associates from bringing about change.” Greenstein, ‘Reagan, Gorbachev, and the End of the Cold War’, p.214; see also pp.214216; and Bisley, End of the Cold War, p.100 65 See ‘Transcript of Press Interview of President at White House’, New York Times, March 30, 1983; quoted in Jervis, ‘Perception, Misperception, and the End of the Cold War’, p.227 66 Jervis writes that the development of SDI should also be seen in this light. Reagan hoped that it would make nuclear weapons superfluous.; Jervis, ‘Perception, Misperception, and the End of the Cold War’, p.227 63 64 27 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 ments may have been essential in reducing overall tensions between the two sides; yet their shared view on such a fundamental issue most definitely gave both leaders the confidence that they would be able to do business with the other. Similarly, as already mentioned, Gorbachev’s joint message of reform and political independence for eastern Europe coincided with a number of regional factors he had not reckoned with, such as the increasing force of Western ‘benign power’ and a strong residue nationalism. As a result, the former satellites quickly looked West and Gorbachev’s hope that they might adopt similar reforms towards social democracy fell flat on their face.67 4.4 How the Cold War Ended The underlying causes for the end of the Cold War, present at the outset, were (1) ‘new thinking’, (2) Soviet economic decline, (3) the appointment of Mikhail Gorbachev as General Secretary of the CPSU, and (4) Ronald Reagan’s incumbency of the White House. Without these it is impossible to imagine the end of the Cold War, at least remotely in the way that it happened. They were thus non-redundant elements within the greater causal complex which eventually brought the Cold War to an end. However, they were all in and of themselves insufficient as causes. What finally made the greater causal complex in which they were embedded causally sufficient to ‘produce’ the end of the Cold War, then, was a number of catalysts, nonlinear confluences of separate causal chains, and the fortuitous timings of both the former and the latter. It was not, therefore, any individual cause, or even all of them together, but the particular way they related to each other. I will go through the most important of these in roughly chronological order. The first important confluence—that is, the one which started the process which led to the end 67 Compare Koslowski and Kratochwil, ‘Understanding Change in International Politics’, pp.127-165 28 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 of the Cold War—was provided by the fortuitous near-simultaneity of the dying-out of some important members of the Brezhnev generation, the coming-of-age of ‘new thinking’, and the continued stagnation of the Soviet economy in the early 1980s. All three originated from independent causal chains and did not cause, or were the result of, one or the other. This goes without saying for the first, the deaths of Andropov and Chernenko, but may be less obvious for the other two. Yet, ‘new thinking’ did not develop, or was suddenly ‘deployed’, because of a crisis in the Soviet economy. It was much older in origin, and its roots—and incidentally its convictions and beliefs—went much deeper. According to ‘new thinking’, openness and reform were the solution to the crisis faced by the Soviet Union, not to please the West or even to end the communist-capitalist standoff, but to reinvest socialism with renewed strength and vigour. That these chains of causation coincided, through their fortuitous timing, was instrumental for subsequent developments, as the confluence between them provided the catalyst for a first retrenchment of Cold War positions. Their coinciding was particularly important because the timing of their confluence, in turn, coincided with another crucial factor: Ronald Reagan’s second term in office. For Gorbachev to be able to maintain the momentum for his reforms, he needed an American counterpart who would, so to speak, ‘reward’ him for his efforts to reduce tensions, by taking him seriously and providing him with a platform for change, both at home and abroad. By creating a climate for serious and open dialogue, Reagan was in a unique position to do just that. It is far from clear whether a president Bush would have been able to act in the same confident manner if Reagan had died in the attack on him in 1981.68 Reagan, however, had a strong reputation as a hardened anticommunist and had spent most his first term in office denouncing communism in 68 Greenstein, ‘Reagan, Gorbachev, and the End of the Cold War’, p.216 29 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 general, and the Soviet Union in particular. This timely confluence between the willingness of one leader to enact reforms and another who ensured, then, that Gorbachev’s reforms lost none of their momentum. In fact, they were further accelerated by another important confluence. This was between Gorbachev’s openness to ‘new thinking’ and his strong leadership skills and highly flexible mind. The combination between all three ensured that ‘new thinking’ would not only be at the forefront of Soviet policy, both domestically and abroad, but that it would also quickly supersede itself as the initial reforms were rapidly making way for a move towards democracy and an increasing social-democratisation of socialism as a whole. This provided two important catalysts. The change in Gorbachev’s mindset regarding the threat posed by capitalism and the West led so far that he eventually renounced communist ideology altogether. This provided an important catalyst for change as it fundamentally altered Reagan’s perception of the Soviet Union69 and, therefore, changed the relationship between the two countries to such an extent that an end to the Cold War was now in sight. The second important catalyst was provided by Gorbachev’s abandonment of the Brezhnev Doctrine. Having introduced his reforms in the Soviet Union, Gorbachev urged the countries of the Eastern bloc to implement similar reform programmes. He regarded the liberalisation of these regimes as a necessary precondition to instil within them a renewed legitimacy, and thus to make them fit for the future. Yet, by giving them their freedom to choose, Gorbachev unleashed local dynamics that he was unable to contain, and which quickly led to the end of communism in the former satellites. The end of the Brezhnev Doctrine, therefore, provided an important catalyst for the rapid unravelling of communism in Eastern Europe. 69 Jervis, ‘Perception, Misperception, and the End of the Cold War’, pp.225-231 30 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 Finally, there are a number of factors which may or may not have served as important catalysts and confluences for events which led to the end of the Cold War. Among these are the disaster of Chernobyl and Matthias Rust’s flight to Red Square. Similarly, the improved relations between the two groups of leaders may have enabled them on occasion to go further than they would otherwise had. These factors also include the trust that may have developed in the dealings between Gorbachev and Reagan following their shared view on nuclear weapons. It is difficult to say what impact these had, and whether or not they facilitated anything that would otherwise not happened. On balance, they probably did in some way or another, but it would require a detailed study of them all to say this with any measure of certainty. In summary, then, the Cold War ended not because of the dying-out of the hardliners, because of the Soviets’ economic difficulties, or because of Gorbachev’s selection as General Secretary; not because of Ronald Reagan’s ability to engage with the Soviets; and not because of the input of ‘new thinking’, or because of the gradual retreat of revolutionary ideology; not either because of the abandonment of the Brezhnev Doctrine, or even because of the centrifugal tendencies within Eastern Europe. It ended because of the nonlinear catalysts provided through all these factors’ timely interaction and confluences which drew them together and made them, thereby, causally effective to lead to an outcome that we call the end of the Cold War. 5. Conclusions To give a unified account of the events which led to the end of the Cold War, it is important that we do not conceive of the end of this conflict as the result of a number of key variations in the entities which were supposedly at its centre. Instead, we must see the Cold War as made up of a number of fluid relations, and the end of the Cold War 31 Florian Wastl, 13 February 2008 as the result of catalysts which were brought about by nonlinear, well-timed, confluences between these relations. This also highlights the more general importance of seeing social configurations such as the Cold War not in their states of ‘being’, made up as it were of fixed entities that give them a set of specific features, but in their states of ‘becoming’, as fluid configurations. It is not possible to reduce such configurations to any constituent parts and to account, in a linear fashion, for a change in the former by means of a change in the latter. This also means, of course, that complex events like the end of the Cold War are impossible to predict, as their development proceeds through fortuitous timings and confluences of an essentially nonlinear nature. 32