Research Stream on Business and Politics

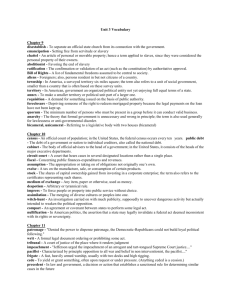

advertisement