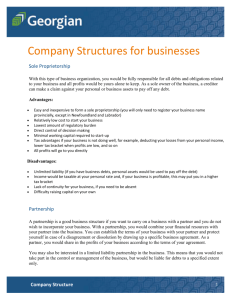

TOPIC 4 A COMPANY AS A CORPORATE ENTITY EFFECT OF

advertisement