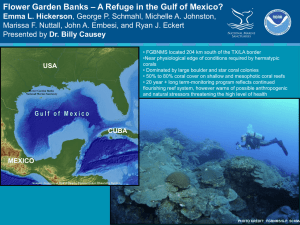

Coral Sea National Nature Reserves Ramsar Wetland: Ecological

advertisement