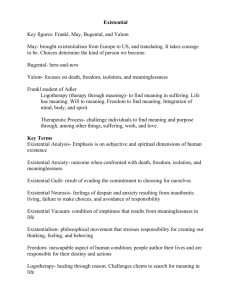

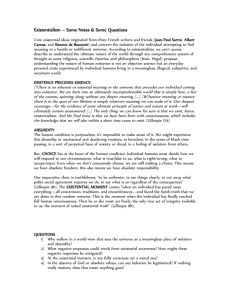

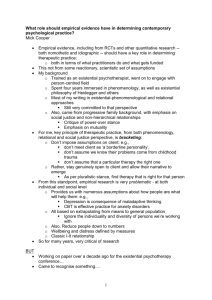

existential psychotherapy

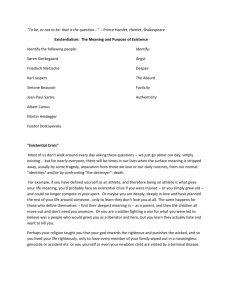

advertisement