Lecture 1

advertisement

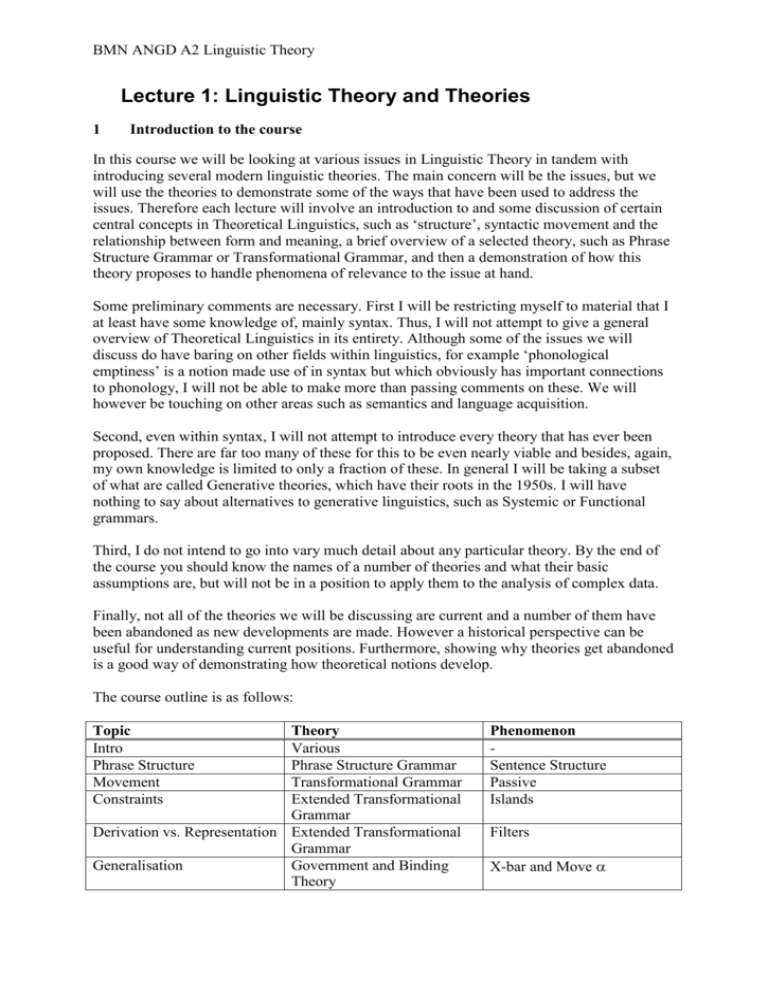

BMN ANGD A2 Linguistic Theory Lecture 1: Linguistic Theory and Theories 1 Introduction to the course In this course we will be looking at various issues in Linguistic Theory in tandem with introducing several modern linguistic theories. The main concern will be the issues, but we will use the theories to demonstrate some of the ways that have been used to address the issues. Therefore each lecture will involve an introduction to and some discussion of certain central concepts in Theoretical Linguistics, such as ‘structure’, syntactic movement and the relationship between form and meaning, a brief overview of a selected theory, such as Phrase Structure Grammar or Transformational Grammar, and then a demonstration of how this theory proposes to handle phenomena of relevance to the issue at hand. Some preliminary comments are necessary. First I will be restricting myself to material that I at least have some knowledge of, mainly syntax. Thus, I will not attempt to give a general overview of Theoretical Linguistics in its entirety. Although some of the issues we will discuss do have baring on other fields within linguistics, for example ‘phonological emptiness’ is a notion made use of in syntax but which obviously has important connections to phonology, I will not be able to make more than passing comments on these. We will however be touching on other areas such as semantics and language acquisition. Second, even within syntax, I will not attempt to introduce every theory that has ever been proposed. There are far too many of these for this to be even nearly viable and besides, again, my own knowledge is limited to only a fraction of these. In general I will be taking a subset of what are called Generative theories, which have their roots in the 1950s. I will have nothing to say about alternatives to generative linguistics, such as Systemic or Functional grammars. Third, I do not intend to go into vary much detail about any particular theory. By the end of the course you should know the names of a number of theories and what their basic assumptions are, but will not be in a position to apply them to the analysis of complex data. Finally, not all of the theories we will be discussing are current and a number of them have been abandoned as new developments are made. However a historical perspective can be useful for understanding current positions. Furthermore, showing why theories get abandoned is a good way of demonstrating how theoretical notions develop. The course outline is as follows: Topic Intro Phrase Structure Movement Constraints Theory Various Phrase Structure Grammar Transformational Grammar Extended Transformational Grammar Derivation vs. Representation Extended Transformational Grammar Generalisation Government and Binding Theory Phenomenon Sentence Structure Passive Islands Filters X-bar and Move Mark Newson About Nothing Meaning and Grammar Grammatical Functions Relative and Absolute grammaticality Explanation Words Language Acquisition 2 Government and Binding Theory Government and Binding Theory Lexical Functional Grammar Optimality Theory Raising and Control Minimalist Programme Distributed Morphology Various Feature Checking Tense and do-insertion - Θ-roles and binding Passive Auxiliary Inversion Why Do We Need Theory? In this lecture I want to set the scene by giving a brief overview of the history of theoretical linguistic thought, to put some historical perspective on the theories we will be looking at later in the course. But before we embark on this programme, I want to address an issue that some find troubling: why do we bother with theories at all! After all, isn’t it just a matter of observing linguistic phenomena, such as the words people say and the orders they put them in to mean certain things, and then putting these observation into some neat description? All theories seem to do is make things impossibly complex and are only therefore of any interest to those perverted enough to get a kick out of such things. My answer to this is quite simple. Theories are unavoidable and it is impossible to get anywhere without a theory. There are at least two reasons for this. 1. The human mind has an in-built hard-wired theory of the universe It is probable that our minds operate with a basic set of general concepts which are used to form new and more complex concepts. However, the very fact that it is a system necessarily means that it is limited – though of course, it is difficult to conceptualise of something that we cannot conceptualise of and so it is hard to determine where the limits of the system lie! Although this conceptual system is clearly very successful in coming to terms with the world which we live in and has enabled us to achieve some remarkable feats of technology and engineering, we cannot know that it is completely compatible with a full and proper understanding of the entire universe. Indeed it would be remarkable if the human conceptual system had developed in such a way as to enable this. The important point, however, is that when we come to try to understand the universe, we do not start with a totally clean slate: we use our conceptual system to impose an understanding on what we observe. In other words, from the earliest human endeavours to understand the universe, we have done so with a preconceived theory which has been imposed on us from our biology. Over the years we have been able to modify this theory and develop new concepts which help us to understand the universe to a greater extent, but clearly we cannot escape our conceptual system and any understanding we gain of the universe and anything within it will be confined by this system. 2. To universe is too large and complicated to understand 2 Linguistic Theory and Theories One clear limitation on the human mind is that it is not able to comprehend past a certain degree of complexity. Though there are some individuals that we consider to be very clever, there is no one alive today that encapsulates all current human knowledge and the idea that any one individual could possibly come to an understanding of the entire universe is clearly laughable. The typical strategy humans have adopted when trying to understand an impossibly complex universe is to chop it into smaller bits which are hoped to be more manageable. This strategy has met with a certain degree of success. However, it is not always a straightforward strategy to implement. First it assumes that it is true that the universe naturally comes in simpler bits, which is logically not necessarily a property of the universe – it would be a very convenient fact if it were true because it might enable us to make scientific progress. But this is no reason to believe that the universe is so constructed. Second, in order to split something up into parts to make an understanding of its whole possible presumes some knowledge of the thing to know how to split it up in helpful ways: breaking water up into its oxygen and hydrogen atoms can tell us a lot more about what water is than, for example, pouring it into cups. For example, we can explain why certain gasses dissolve in water by understanding its molecular properties, but the fact that it can be poured into a number of different sized cups tells us nothing about this. Thus we are faced with a catch 22 situation: in order to break up the universe so that we might understand it we need to be able to understand the way it can be usefully broken up, which implies a certain understanding of it before we even start. The way round this problem is simply to guess at the possible correct way of splitting up the universe and use this guess to see if anything useful can be discovered. If yes, the guess seems to be a good one and it can be maintained for finding out more, and if no the guess is a bad one and should be abandoned in favour of another. Such guesses are more commonly called theories and we can clearly see that theories are a necessary part of our understanding as without theories about the way the universe breaks up we cannot even make a start. It turns out that to be able to interpret any set of observations in order to gain understanding of what is observed it is necessary to make assumptions about what we are observing: how it is different from and related to other things in the universe and how it is organised within itself. Without such assumptions, any observation will be uninterpretable and therefore utterly useless in trying to understand anything. In short, observations only count as data with respect to a set of assumptions – i.e. a theory. 3 Basic assumptions in Linguistic Theories Thus it turns out that theories are unavoidable necessities in the process of coming to understand the universe and the things it contains. The study of language offers a very clear demonstration of this. To start with, any study of language is going to have to distinguish language from the rest of the universe. At first this may seem trivial as it seems quite easy to distinguish between language and a piece of granite or a hydrogen atom. However things become more tricky when we try to distinguish language from thought, speech or communication, for example. While I don’t wish to enter this particular debate, it does illustrate that the divisions we make 3 Mark Newson in studying the linguistic part of the universe are not ‘given’ and moreover whatever decision is made as to how to split these things up will clearly have an impact on the study itself. Most of the theories we will be looking at in this course take a fairly uniform perspective on this issue. The ‘generative perspective’ tends to view the object of study of linguistics to be the body of knowledge that speakers have concerning the construction of well formed linguistic expressions. In this sense language is part of the mind and is distinct from other parts of the mind, such as our ability to reason and understand, our ability to recognise objects in the visual field, etc. It differs from thought, speech and communication in that these are behaviours that may use linguistic knowledge but should not be equated with it. Hence there is a clear distinction to be made between language knowledge (sometimes referred to as ‘competence’) and language use. Of course there are some who completely disagree and claim that language cannot be studied outside the consideration of its use, but as this is not a clearly visible aspect of language the best we can do is to assume language to be one way or another and see how far we can get on these assumptions. If we take this point of view, then it follows that the study of language has to proceed in a certain way. We have no direct access to the mind and therefore no direct access to language conceived of as part of the mind. In stead we have to observe the behaviours which make use of language and try to figure out what the linguistic system is. For this reason alone, the study of language is not easy. We also have the question of how the linguistic system is itself organised. We all know that linguists tend to group themselves as phonologists, morphologist, syntacticians and semanticists, reflecting common ideas as to how the system itself breaks up. But even this is not so straightforward and there are some who argue that some of these distinctions are invalid, or at least improperly drawn. For example, there is an idea that there is no clear distinction to be made between syntax and morphology in that both of these areas make use of the same processes and that variations in languages determine that sometimes morphemes are realised as independent elements and other times as dependent ones. For example most Bantu languages have words which mark the subject, rather similar to agreement morphemes in other languages, but which are independent of the verb: (1) Neo u no bika nyama Neo sub pres cook meat “Neo cooks meat” Even if linguists agree that there is a line to be drawn between phenomena, there may well be argument about where the line should be drawn. For example some consider both derivational and inflectional morphology to be distinct from syntax whereas other consider inflectional morphology a part of syntax whereas derivational morphology is something different. The argument is that while derivational morphology is lexically idiosyncratic, inflectional morphology is much more productive and regular: (2) argu-ment discover-y tri-al degrad-ation kick- argu-ing discover-ing try-ing degrad-ing kick-ing 4 Linguistic Theory and Theories Again, I don’t want to go into these arguments, but the point is that whether these distinctions should be made and if so where is not something that is easily determined by observation and subsequently there are a number of possible positions one can take and much argument between the different positions. Given that it is clear that no one of these positions is clearly correct, in order to study any linguistic phenomena a prior assumption must be made as otherwise one cannot determine whether one is looking at phenomena that impinges on syntax or not. 4 A Brief History Of (Some) Linguistic Theories While language has been studied for several millennia, I don’t intend this brief history of this study to start at the beginning. What I want to do here is to place the generative school of thought in time, so as to facilitate some understanding of why it developed as it did. An understanding of what the Greeks thought, for example, is not essential for this. Instead we will start with the school of thought that generative linguistics was reacting to when it first emerged. 4.1 American Structuralism Just after the turn of the 20th century a set of circumstances led to the development of a linguistic school of thought in America which was to dominate all others for more than 50 years following. Firstly American science at the time was influenced by a strongly empiricist philosophy, which claims that human knowledge has its source in experience. An extreme form of this influenced a branch of psychology call behaviourism and led them to the claim that science should not entertain notions concerning things which cannot be observed. As the mind cannot be observed, it should not be posited in a theory of psychology. Instead psychological theory should be based on the observable conditions in which humans behave, known as the stimulus, and the behavioural reactions that humans has to such stimuli, known as the response. It has been said that behaviourism was therefore the only school of psychology to define away its own subject matter! The linguists of the time were very impressed with behaviourism and sought to adopt a similar philosophy. Linguistic theory, they claimed, should only be based on what is observable. Given that the only really observable aspect of language is its externalisation in terms of sounds or diagraphs, this did not look very promising as it would limit the study of language to articulatory and acoustic phonetics at most. However, the structuralists reasoned that as long as everything that was postulated at more abstract levels of description of language, such as phonology and syntax, was based on observable things (i.e. sounds) then everything would be OK. To ensure this it was proposed that phonological elements must have a phonetic base, morphological elements as phonological base and syntactic elements a morphological base, so that everything is ultimately rooted in phonetics: (3) Syntax Morphology Phonology Phonetics 5 Mark Newson To give some idea of how this was supposed to work, consider the definition of a phoneme in this system. Essentially a phoneme could be defined as a set of phones used in certain phonetic environments. So, for example, the phoneme \t\ could be defined as the phones [t], [th], etc., which are connected by a complementary pattern of distribution. One of the consequences of this theory was that semantics was seen to have no part in linguistics, meanings being essentially unobservable. Indeed, semantics was deemed to be a proper branch of physics, with the meaning of a word being only properly rendered in a complete physical description of the object it referred to. For this reason, semantics was not studied by linguists in America for the first half of the 20th century. Another consequence of this hierarchical view of language was the development of the notion of constituent structure in syntax. As we have said, syntax is built on morphology which essentially delivers the notion of the word to the syntactic system. The end point of syntax is the sentence and, of course, so as to maintain that everything is rooted in observable phonetic phenomena, sentences must be constructed from words. But other notions in syntax, such as subjects and objects, for example, seem to be made up of elements bigger than words but smaller than sentences. Thus, the standard syntactic idea that words are built into phrases and phrased into sentences. Ultimately, then, one could give an analysis of a sentence where the sentence was broken into phrases, the phrases into words, the words into morphemes, the morphemes into phonemes and the phonemes into phones: (4) S NP VP N V NP John loves N Mary love s \ The second main influence on the development of structuralist thinking was the urgent need to document existent Native American languages, many of which were rapidly becoming extinct. The task was then to train field workers to be able to go out and document as many languages as possible, as accurately as possible and in as short amount of time as possible. Early investigations into Native American languages had shown that here was an important source of information concerning phenomena which apparently differed vastly from IndoEuropean. This meant that standard traditional grammatical notions, developed from classical studies, were unlikely to be much use to the job at hand. Moreover, the structuralist belief that semantics was not an admissible source of scientific information rather hampered the task, as ideally language should be studied without reference to what words and sentences 6 Linguistic Theory and Theories mean. However their hierarchical view of language seemed to offer a way to crack the problem which was not reliant on more traditional notions. The main task was seen to provide field workers with ‘discovery procedures’, which when applied to linguistic data would yield accurate descriptions of the linguistic system. For example, complementary distribution and minimal pair tests could be used on the set of observed phones used in a language to discover its phonemes, distributional analyses would reveal the set of morphemes and word categories, etc. 4.2 The sudden rise of the Generativist School Structuralist linguistics was the leading American school until the late 1950s. Noam Chomsky was a student of one of the leading structuralists of the time, Zelig Harris. In the early 1950s Chomsky started to develop a view on linguistics which took exception to a number of the leading ideas of structuralism, though at the time he had little success in publishing his work. It was not until 1957 that Chomsky was able to publish anything based on his own developing framework, and even that was not a full exposition of the theory and neither did it come out openly against the structuralist tradition, being a course text for computing students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Nonetheless, it was enough to influence the course of development of the subject in America, and indeed most of the rest of the world, and so the Generative school of linguistics was born. In later writings, Chomsky attacked some of the fundamental assumptions of the structuralist tradition, starting with its radical empiricist stand point. In 1959 he wrote a damning criticism of a book by a leading behaviourist, Skinner, which pointed out fundamental weaknesses not only of behaviourist principles, but of its entire empiricist basis. This review virtually ended the leading role that behaviourism had in psychology and at the same time exposed similar weaknesses in the structuralist framework. From Chomsky’s point of view, only a rationalist position made any sense, from which language was to be understood as a system of the mind, which was clearly not directly observable. This perspective opened up many paths for the investigation of language as, once free from the restrictions that only directly observable data can be considered, many other observations, including ones concerning meaning, could be taken into consideration. Chomsky was also highly critical of the notion of discovery procedures, claiming that it was absurd to believe that such as set of ‘fool proof’ procedures should exist and pointing our that once a rationalist perspective was adopted one simply was not restricted to such things for collecting evidence about language. The way to study language, Chomsky argued, was, by using any data available, including intuitions, introspections, grammaticality judgements, etc., to formulate a set of rules which correctly analyses the data and then to test these rules on further data to refine them. The rules must be explicitly stated so that we can know precisely what they predict about future data in order to test their validity. Such an explicit set of rules, he called a ‘generative grammar’. It wasn’t this aspect of Chomsky’s work, however, that captured the attention of most linguists in 1957 – indeed, many structuralists who praised Chomsky’s original work were aghast to find out what he really believed! 7 Mark Newson Chomsky was not against every aspect of structuralist work. For example, he took on the notion of constituent structure as one of fundamental aspects of his own system and even formalised it in what he called a Phrase Structure Grammar, made up of rules of the following form: (5) X→YZ This kind of rule tells us about the immediate constituents of a structural unit: it says that a unit of type X has units of type Y and Z as its immediate constituents. In other words, we have the following structure: (6) X Y Z However, what really made an impact at the time was Chomsky’s argument that this kind of grammar was not enough to handle natural language phenomena, as this demonstrates noncontinuous constituent phenomena. That is, a constituent which appears spread across a structure, for example: (7) a man walked by who I knew Here the relative clause who I knew modifies the subject a man and so seems to form a constituent with it. However the two parts of the constituent are at opposite ends of the sentence with the VP walked by separating the two. Chomsky demonstrated that such phenomena could not be handled by a Phrase Structure Grammar and therefore proposed that another grammatical device was also required: a transformation. Transformations are rules which operate on structures to alter them in some way. For example, a movement transformation would take a structure containing an element X in position Y and produce a related structure in which X is in another position Z. Thus an analysis of the sentence in (7) might be: (8) S NP Det N S VP S V transformation P Det N a man who I knew walked by 4.3 NP VP V S P a man walked by who I knew Generative Grammar in the 1960s and 70s At the end of the 1950s the generative school rapidly became the dominant one in America and its influence started to spread worldwide. Its first five or so years were expansionist in that people sought further applications for transformations. However to some extent this conflicted with another concern of Chomsky’s, which also followed his rationalist stand point. 8 Linguistic Theory and Theories Once generative grammars became more fully articulate, it was apparent that such systems were highly complex: at least as complex as the range of linguistic phenomena demonstrated by known languages. Yet Chomsky pointed out that knowing a language was one of the basic properties of every normal human being and so an important issue to address was where this knowledge comes from. It is clear that we cannot simply say that children are born ‘knowing’ their language, as they all go through some process of language acquisition. Moreover, such a blunt rationalist approach would not be able to account for why there is more than one language and why the linguistic environment of the child has an effect on the language that the child develops. At the same time, in his criticism of Skinner’s behaviourist approach, Chomsky had convincingly argued that a completely empiricist approach to the problem of language acquisition was not tenable: the environment alone could not possibly account for how children acquire such complex systems in such a sort amount of time. From a linguistic point of view the problem facing early transformational grammars was that if the grammars were to account for complex linguistic phenomena, there would seem to be no limit to what we would need the grammar to be able to do. But such an unlimited grammatical system would not shed any light on the problem of language acquisition as they provided nothing to attribute to the child to help cut down the problem of learning complex systems from limited experience. From the early 60s Chomsky therefore forwarded the idea that a linguistic theory that could shed light on the problem of language acquisition was to be preferred to one that did not as it would therefore attain a level of ‘explanatory adequacy’ as opposed to ‘descriptive adequacy’. From about the mid 1960s therefore the search was on for a way to make transformational grammars more limited and thus more explanatory: if a transformational grammar had to operate within limits, we might attribute those limits to properties of the human mind and in turn this would reduce the complexity of the acquisition process as children would not be able to entertain any hypothesis about the language they were acquiring, but they would be restricted to those that lay within the limits of their own mental structure. In effect, this turned attention away from the question of what linguists can do with transformations and towards the question of what they cannot do with them. Perhaps we might gain an understanding of the limits of the human linguistic system by observing what, though logically possible, doesn’t actually happen in languages. The first step in this process was the proposal of ‘constraints’ on transformational processes. We will discuss this development in a future lecture, but to give some idea consider the following sentences: (9) a b c which tree did you see him over by over by which tree did you see him * by which tree did you see him over It would appear that the nominal phrase which tree can be extracted out of the complex PP over by which tree. Furthermore, this whole PP can also move. However (9c) indicates that the PP by which tree cannot be moved out of the complex PP. This is puzzling as clearly some things can move out of PPs and some PPs can move – so why not this one? Chomsky’s original proposal was that movements are restricted to prevent an element of a certain category moving out of a structure of the same category. Thus while nominal phrases can be extracted from PPs and PPs can be extracted from VP, a PP cannot be extracted from a PP. This was termed the A-over-A condition: an element of type A cannot be moved over (i.e. out of) another element of type A. 9 Mark Newson One of the most positive consequences of this direction of investigation was that as more was noted about what could not be done with transformations, the more general the statement of transformations became. This is because if we only consider what happens in a given phenomena and try to describe it, we end up with a very specific and complex description of the process. However, the more we consider what transformations in general are not capable of, the more we can factor out certain complications. So for example, if no movement can violated the A-over-A condition, we do not have to build in the effects of this condition to any particular transformation. The more general constraints we observe, the more general the description of transformations can become. Partly as a consequence of this process, other notions were introduced into transformational grammar during the 1970s, such as X-bar theory and the trace theory of movement. The theory that emerged came known as Extended Standard Theory, ‘standard theory’ being the one that developed at the start of the 1960s. 4.4 Generative Grammar in the 1980s Throughout the 60s and 70s most efforts in developing generative grammar were fairly homogenous. Towards the end of the 70s, however, some differences of opinion as to the direction the theory should take became visible. Some of the issues concerned the question of whether we actually need transformations or not. Thus from the beginning of the 1980s there were several attempts to build generative grammars with very different properties to those that had until that point been considered. One of these was Generalised Phrase Structure Grammar, which attempted to build in other mechanisms to the Phrase Structure Grammar originally described by Chomsky in the 1950s to account for ‘movement’ phenomena. Another was Lexical Functional Grammar, which saw sentence structure as being the result of mapping certain elements onto grammatical functions, such as subject and object, which were taken to be basic to the system. Chomsky himself saw that the developments of the 1970s led to the possibility of a highly articulated basic theory of human language, which he termed Universal Grammar. The description of linguistic processes had been able to be made so general by the development of constraints that they were now able to be applied to a wide variety of linguistic phenomena that cut across different language boundaries. Thus it appeared for the first time that we could identify grammatical principles which were not specific to individual languages, but indicative of some underlying system that all human languages shared. If it were possible to articulate such a theory, much progress could be made towards Chomsky’s goal of explanatory adequacy. The principles of Universal Grammar could be assumed to be descriptions of the structure of the human mind and hence provide a radically limited view of human language which could explain the possibility of language acquisition: children are born with Universal Grammar by the very fact that they were born with human minds. All that had to be acquired is the more peripheral features that allow one language to differ from another. The theory that developed in the 1980s along these lines was known as Government and Binding theory. We will have much to say about this in future lectures. 10 Linguistic Theory and Theories 4.5 The 1990s For one reason or another, from the beginning of the 1990s interest began to switch from viewing grammars as a set of rules or principles that have to be adhered to in order for grammaticality to be obtained, to more of a view that grammaticality was to be defined in terms of a set of possible alternatives. From this point of view, grammaticality is not absolute, but relative. To see this idea consider the following data: (10) a b he did not leave * he did not have left (10a) illustrates phenomena known as do-insertion: the auxiliary do is used to bear tense in certain negative English sentences. (10b) gives an example of a negative English sentence where do-insertion is not possible. The question to be answered is why do cannot be used in this case. After all, it is a possible process made available in English. An absolute approach to this problem would seek to find a grammatical rule which was violated by (10b) but not (10a). A relative approach might consider the following observations as relevant: (11) a b * he not left he had not left The observation is that in negative sentences tense can be born by an auxiliary but not by a main verb. Hence the insertion of do would be unnecessary when there is an auxiliary present and it might be this fact that accounts for the ungrammaticality of do-insertion in these circumstances. With main verbs, however, do-insertion is possible as there is no other choice. In other words, (10a) is grammatical because (11a) is not and (10b) is ungrammatical because (11b) is grammatical. From this perspective grammaticality is defined as relative to what the alternatives are. One theory which makes relative grammaticality a central notion is Optimality Theory and this has developed in ways which are quite different from either previous or current generative systems. We will spend some time on issues concerning this approach towards the end of this course. Although Chomsky started the 1990s with an interest in relative grammaticality and indeed was one of the main proponents of this notion at the start of the decade, he has become even more concerned with another aspect of linguistic theory development: that of achieving even greater levels of explanation. The notion of explanation in any science is a difficult one to pin down: what counts as an explanation of phenomena? Chomsky’s thoughts on this issue have led him to the conclusion that we should try to eliminate all but absolutely necessary mechanisms from consideration in trying to formalise grammars. Chomsky calls this the Minimalist Programme. A final development we will be concerned with which has its origins in the 1990s is Distributed Morphology. This questions the standard view that the syntactic system manipulates lexical items, which are seen as primary and given. Instead it is proposed that the syntax works with more abstract elements of a universal and semantic nature, combining these in different ways into structures. Only once the structure is built does the language system ‘spell out’ the structure in terms of vocabulary items, which are seen as mappings from collections of syntactic-semantic features into phonological forms. In other words, what 11 Mark Newson might be traditionally recognised as words are inserted into a structure only at the end of the linguistic processing. This idea sheds new light on our thinking about what words are and how these are used to represent syntactic and semantic constructs. 5 Conclusion In this lecture we have argued that it is impossible to study language, and indeed the whole of the universe, without making some initial assumptions about it in order to be able to interpret observations concerning it. In other words, theories come first and data can only be interpreted with respect to a theory. It follows that in order to make progress in our understanding we need to be explicit about our theories in order that we are able to hold them up for scrutiny, in case the data indicates that they are in error (something that is very likely). The generative school takes this point of view seriously and insists that a linguists grammar, i.e. a grammatical theory, be as explicit as possible so that it is itself open to scientific investigation. We have given a brief history of some of the ideas that have come out of this school since the 1950s. In the following lectures, we will add more details to show how linguistic theory has developed to the present day. 12