Are the Old Ways New Again? - Anthropology at Missouri State

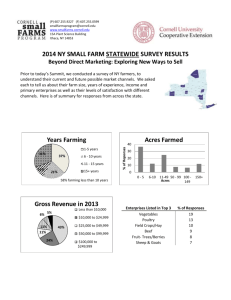

advertisement