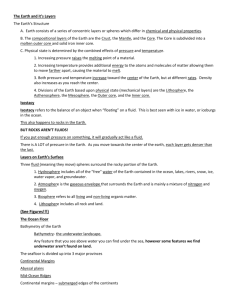

Key Concept Review (Answers to in-text “Concept Checks”) Chapter

advertisement

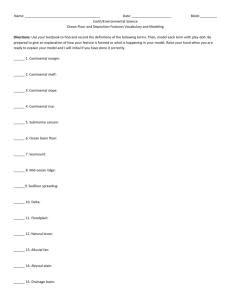

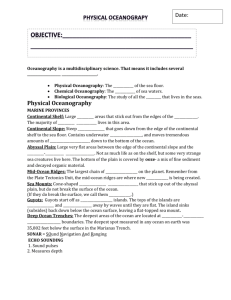

Key Concept Review (Answers to in-text “Concept Checks”) Chapter 4 1. The simplest methods involved lowering a weight on a line. The length of line is measured, and the depth determined. Sometimes the weight was tipped with wax to retrieve a sample of bottom sediment. Scientists now use beams of sound to measure depth. 2. Echo sounders sense the contour of the seafloor by beaming sound waves to the bottom and measuring the time required for the sound waves to bounce back to the ship. Unlike a simple echo sounder, a multibeam system may have as many as 121 beams radiating from a ship’s hull. 3. Satellites cannot measure ocean depths directly, but they can measure small variations in the elevation of surface water using radar beams. This is useful because the pull of gravity varies across Earth’s surface depending on the nearness (or distance away) of massive parts of Earth. An undersea mountain or ridge “pulls” water toward it from the sides, forming a mount of water over itself, and that mount is detected by the orbiting satellite. 4. Ocean basins are not bathtub-shaped. The submerged edges of continents form shelves at basin margins, and the center of a basin is often raised by a ridge. 5. The transition to basalt marks the true edge of the continent and divides ocean floors into two major provinces. The submerged outer edge of a continent is called the continental margin. The deep seafloor beyond the continental margin is properly called the ocean basin. 6. The continental margin is characterized by thick (and less dense) granitic rock of the continents. Near shore the features of the ocean floor are similar to those of the adjacent continents because they share the same granitic basement. Relatively thin (and denser) basalt forms the adjacent deep seafloor. 7. The continental slope, shelf break, continental slope, and continental rise are the main features of continental margins. 8. Continental margins facing the edges of diverging plates are called passive margins because relatively little earthquake or volcanic activity is now associated with them. Continental margins near the edges of converging plates (or near places where plates are slipping past one another) are called active margins because of their earthquake and volcanic activity. 9. The width of a shelf is usually determined by its proximity to a plate boundary. The shelf at a passive margin is usually broad, but the shelf at the active margin is often very narrow. 10. Figures 4.15 and 12.2 provide graphs of sea level through time. Sea level is high at the moment, and is rising as the ocean warms. 11. Submarine canyons cut into the continental shelf and slope, often terminating on the deep-sea floor in a fan-shaped wedge of sediment. Most geologists believe that the canyons have been formed by abrasive turbidity currents plunging down the canyons. 12. Along passive margins, the oceanic crust at the base of the continental slope is covered by an apron of accumulated sediment called the continental rise. Sediments from the shelf slowly descend to the ocean floor along the whole continental slope, 1|Page but most of the sediments that form the continental rise are transported to the area by turbidity currents. 13. Oceanic ridges are Earth’s most remarkable and obvious feature. Other deep-ocean features are abyssal plains, seamounts, fracture zones, and the deep trenches. 14. Oceanic ridges stretch 65,000 kilometers. Although these features are often called mid-ocean ridges, less than 60% of their length actually exists along the centers of ocean basins. 15. Check Figures 4.26 and 4.27 after you make your drawing. 16. Fracture zones extend outward from the ridge axis. They are seismically inactive areas that show evidence of past transform fault activity. While segments of a lithospheric plate on either side of a transform fault move in opposite directions from each other, the plate segments adjacent to the outward segments of a fracture zone move in the same direction. 17. Abyssal plains are flat, featureless expanses of sediment-covered ocean floor found on the periphery of all oceans. Abyssal plains are extraordinarily flat. 18. Abyssal plains are relatively rare in the active Pacific, where peripheral trenches trap most of the sediments flowing from the continents. 19. Guyots are flat-topped seamounts that once were tall enough to approach or penetrate the sea surface. The flat top suggests that they were eroded by wave action when they were near sea level. Movement of the lithosphere away from spreading centers has carried them outward and downward to their present positions. 20. A trench is an arc-shaped depression in the deep-ocean floor that forms where a converging oceanic plate is subducted. 21. Trenches are curved because of the geometry of plate interactions on a sphere. The convex sides of these curves generally face the open ocean. The trench walls on the island side of the depressions are steeper than those on the seaward side, indicating the direction of plate subduction. Trenches are prevalent in the western Pacific because that is an area of vigorous plate subduction. 22. Seeing the whole picture at once has its advantages. Patterns not discernable from looking at individual pieces of the puzzle can jump out. Look, for instance, at the area south and east of South America (and north and east of the Antarctic’s Palmer Peninsula) in Figure 4.33 – notice the strong suggestion that the moving sea floor has smeared those projections eastward? 2|Page