NU-clinical-handbook - Department of Psychology

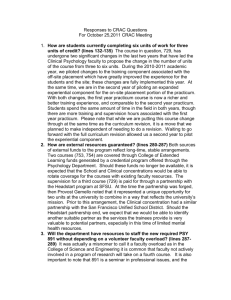

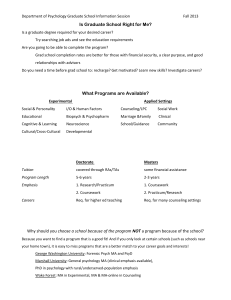

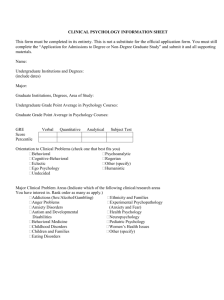

advertisement