Bob Gregory

advertisement

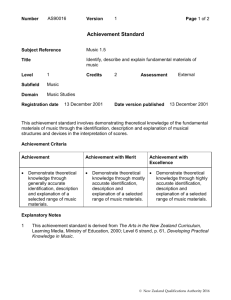

Theoretical Faith and Practical Works: DeAutonomizing and Joining-Up in the New Zealand State Sector Paper prepared for the SCANCOR Workshop, in conjunction with the Structure and Organization of Government Research Committee of IPSA, on ‘Autonomization of the State: From Integrated Models to Single Purpose Organizations’, Stanford University, 1-2 April 2005 Bob Gregory School of Government Victoria University of Wellington Wellington New Zealand Email: Bob.Gregory@vuw.ac.nz (Draft only, please contact the author before use) 2 Abstract New Zealand has now entered the stage of ‘second generation’ state sector reform. Legislation passed by Parliament in December 2004, signals a major attempt to overcome problems resulting from the structural fragmentation that resulted from the ‘first generation’ reforms of the 1980s and 90s. After five years in office, the current government is seeking to strengthen the centre’s ability to enhance the accountability of so-called ‘arm’s length’ agencies (crown entities) and safeguard standards of ethical probity across the state sector as a whole (as distinct from the Public Service as such). The government has also introduced reforms to enhance a ‘whole of government’ capability based on greater inter-organizational cooperation in the quest to achieve officially sanctioned policy outcomes rather than simply producing departmental outputs. However, despite these statutory initiatives, the central institutional features of the first generation reforms remain largely unaltered. Consequently, the new moves will require high levels of political skill on the part of senior state sector executives. Further, while the first generation reforms were shaped by a coherent (if inadequate) theoretical framework, in the form of public choice and agency theories, the latest changes are essentially pragmatically reactive, driven by political experience and administrative practice, and only implicitly acknowledge the shortcomings of the original theoretical design. The New Zealand experience carries implications for the relationship between theory and practice in public policymaking for state sector development. 3 Introduction New Zealand has now entered the stage of so-called ‘second generation’ state sector reform. ‘First generation’ reform comprised the radical changes introduced from the mid-1980s to the early 90s, and which established New Zealand’s place as a world leader in the movement that later became known as New Public Management. These reforms involved a massive programme of privatization of publicly-owned utilities (including the telecommunications services, railways, the national airline and the Bank of New Zealand); the corporatization of government trading organizations in the form of state-owned enterprises (SOEs); the creation of a plethora of stand alone single-purpose crown entities (as they are called) not in the Public Service as such and thus not subject to direct ministerial control; the separation of departmental policy advice from departmental operations (service delivery); the monitoring and review of senior executive performance; the ‘outsourcing’ of many public goods and services; the formalizing of contractual relationships within the executive arm of government; and the abolition of a central state sector personnel function and the delegation to agency chief executives of responsibility for staff employment in their own organizations (see, for example, Boston et al, 1996; Gregory, 2001; Norman, 2003; Scott, 2001). The architects of the first generation reorganization drew upon bodies of theoretical knowledge to inform their new designs, probably more so than similar reforms undertaken in other countries, and certainly much more than had been the case during earlier governmental reforms in New Zealand. In particular, they believed that public choice theory, agency theory and transactions costs analysis provided them with the theoretical tools that would enable them to transform New Zealand’s governmental landscape in ways that would render an increasingly ‘bureaucratic’ system at once more efficient, accountable, responsive and effective. As one commentator has observed of this period, ‘If ever a country has been run by economists, it was New Zealand’ (Kay, 2003: 61). Not surprisingly, however, experience during the 1990s showed that New Zealand had not in fact created a governmental utopia. The centre-left coalition 4 government, elected late in 1999, probably took a cue from the New Labour government in Britain, which had begun to pull ‘Next Steps’ agencies back closer to the centre (Office of Public Services Reform, 2002). The New Zealand government established a Standards Board to advise it on problems that had been emerging in the state sector during the late 1990s. The original reforms had focused on issues of accountability and efficiency at the operational level of government, but in creating an ‘arm’s length’ relationship between the political executive and government agencies, and in their concern for structural disaggregation, they attenuated strategic capability. So while the government was left with the role of ‘steering’ the ship of state, those who did the actual ‘rowing’ often pulled on their oars in ways that impeded the political executive’s steering ability. A year or so after the creation of the Standards Board the government released a key review of the state sector – the Review of the Centre (2001) 1 – which in turn led to the enactment by Parliament late in 2004 of both new and amending legislation aimed at strengthening ‘whole of government’ strategic capacity, by overcoming problems of excessive structural ‘fragmentation’ and ‘siloization’, the weakening of longer-term executive and managerial capability, and the attenuation of a coherent state sector ethos. This paper suggests that it will be difficult to adequately fulfil the aspirations that lie behind the new legislation so long as some of the main architectural components of the first generation New Zealand reforms remain in place. It discusses why the government is reluctant to make more radical changes, and argues that the theoretical foundations of the original reforms were based on ideologically-driven and largely self-fulfilling assumptions about bureaucratic behaviour, which have become strongly institutionalized. The New Zealand experience highlights enduring questions about the relationship between theory and practice, and science (or scientism?) and politics, in state sector reform. 1 See ‘Review of the Centre’ at http://ssc.govt.nz 5 The latest legislative changes The State Owned Enterprises Act 1986, the State Sector Act 1988, and the Public Finance Act 1989 continue to stand as the three statutory pillars of New Zealand central government. The new legislative package comprises four separate enactments, three of which amend the foundational legislation while the other is a new statutory entity now constituting the fourth central component of the state sector legislative framework.2 The State Sector Amendment Act (No 2) 2004 Before the first generation reforms the State Services Commission (SSC) was the government’s central personnel agency, administering a unified career service, with standard pay rates and working conditions right across the state sector. This major, long-standing, function was abolished by the reforms, and responsibility for personnel policy (within common standards) was delegated to the chief executives of each state sector agency. They could ‘hire and fire’ as they individually saw fit. An early attempt to create a Senior Executive Service as a cadre of top executive talent within the Public Service as a whole soon fell by the wayside as chief executives became understandably preoccupied with the personnel requirements of their own separate agencies. The new amending Act empowers the State Services Commissioner to review the machinery of government across all areas of government, and gives that officer a wider mandate to build integrated capability and provide stronger leadership in the maintenance of standards across the state sector as a whole. Previously, the Commissioner’s writ extended only across the departments and ministries comprising the Public Service. The Act entrusts the Commissioner with the responsibility for promoting a strategy to develop senior leadership and management capability in the Public Service, and gives him or her discretionary power to do so across the whole of the state sector. In doing so the Commissioner 2 The Crown Entities Act 2004; The Public Finance Amendment Act 2004; The State Sector Amendment (No 2) Act 2004; and the State-Owned Enterprises Amendment Act 2004. The last of these contains essentially technical provisions only and is not discussed in this paper. 6 will now exercise shared responsibility with departmental chief executives, and may at his or her discretion issue ‘guidance’ to chief executives of the Public Service in developing senior leaders and managers in their respective departments. The new legislation requires chief executives to ‘cooperate’ with the Commissioner but to ‘comply with any reasonable request’ made by that officer. This development reinforces what has been occurring over the past three years, as the government has actively discouraged the use of outside consultants in favour of growing in-house employment.3 (One large department had found that it did not have sufficient competent staff to write its own annual report to Parliament.) The government has expressed concern over the apparent attenuation of the socalled ‘public service ethos’, and there is also some evidence – albeit still indeterminate – of increasing corruption in the New Zealand state sector (Gregory, 2002). Against this background the Commissioner has now been given a mandate to set minimum standards of integrity and conduct across the Public Service and crown entities (but not SOEs), and in the main agencies are required to comply with such standards. Serious breaches of minimum standards may be reported by the Commissioner to the responsible minister. The Public Finance Amendment Act 2004 This Act, which the Treasury describes as a ‘major rewrite’ of the Public Finance Act but ‘not a major reform’ (New Zealand Institute of Public Administration, 2005), is intended to provide an antidote to the effects of ‘siloization’. This is the term commonly used in New Zealand to describe the propensity of departments and agencies to focus on the production of their own outputs rather than to work cooperatively in pursuit of policy outcomes which by their very nature demand an integrated, ‘co-productive’, approach. The new Act is meant to better facilitate ‘joined-up’ government. 3 Just prior to the 1980s reforms there were about 90,000 public servants. By the late 1990s there were around 30,000. Today, the numbers have risen to nearly 40,000. 7 The most important change in this regard is that no longer will Parliamentary appropriations necessarily be confined to one output class only. Resourceswitching authority will be devolved to public managers, enabling them to respond to changing circumstances without first having to get Parliamentary approval. But this is not seen to threaten the ability of Parliament to control the ways in which public money is spent. To prevent that happening the Minister of Finance is required to approve multi-[output] class appropriations, with the justifications for them being provided in the Estimates (given to the House before the appropriations are approved). In addition, the new legislation enables a department effectively to transfer its appropriation for outputs to another department. The department formally with the appropriation and doing the ‘purchasing’ from another department, retains the responsibility for the original appropriation. Although the outputs-based structure of the governmental budgetary process remains intact, since it facilitates firm financial control, the Act reinforces the ‘managing for outcome’ moves that have taken place over the past two or three years. These are intended to see that outputs are more systematically related to desired policy outcomes, to better ensure that agency activities are better ‘aligned’ with the government’s objectives.4 The Crown Entities Act 2004 Described by its authors as a ‘world first’ and ‘path-breaking’ (New Zealand Institute of Public Administration, 2005), this new Act is to enhance central control over the large number of ‘crown entities’ established in the 1980s and 90s as single-purpose, stand-alone, agencies, existing in an ‘arm’s length’ relationship with the political executive, after being separated off from their original departmental conglomerates. Today, together with the 35 government departments, there are 17 SOEs, and about 180 crown entities. Crown entities and SOEs almost invariably have their own individual empowering Acts of 4 Outputs comprise the work done by government employees; outcomes are the societal effects that result from this work. 8 Parliament. These empowering statutes have usually said little or nothing about the roles that the Ministers of State Services and Finance might have in implementing ‘whole of government’ requirements, nor have they specified the respective roles of ministers, crown entity boards, and departments relevant to their functions and activities. The Crown Entities Act 2004 changes this. In so doing it defines five types of crown entities: Crown Agents – non-company entities with a close working relationship with the government of the day (for example, the Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand, and district health boards). Autonomous Crown Entities – non-company agencies that do not require a high degree of ministerial control but are still formally required to have regard to the policy of the government of the day (for example, New Zealand Lotteries Commission, and the Mental Health Commission). Independent Crown Entities – non-company organizations that operate at arm’s length from the government, either because they are quasi-judicial or because they must operate and be seen to operate independently (for example, the Commerce Commission, and the Electoral Commission). Crown Entity Companies – which are established under the Companies Act (for example, Television New Zealand Ltd, and crown research institutes). School Boards of Trustees.5 The Act standardizes the governance requirements for each class of agency, and gives the government the power to direct the agencies collectively to comply with 5 There are about 2,600 school boards of trustees. The main components of the new Act are not directed at this group of crown entities. 9 ‘whole of government’ requirements or those aimed at improving public services. In addition, the minister responsible for a particular Crown Agent may direct the agency to ‘give effect to’ government policy that relates to the agency’s functions and objectives, while a minister responsible for an Autonomous Crown Entity can direct that agency to ‘have regard to’ government policy. But, as before, ministers will have no power to direct an Independent Crown Entity on its statutorily independent functions. Crown entity governing bodies are now subject to generic provisions (such as ‘good employer’ and equal employment opportunity requirements), and except in particular circumstances must comply with minimum standards of integrity and conduct as set by the State Services Commissioner. In a change reflecting public controversies in the late 1990s over remuneration packages paid to some crown entity executives, the new Act requires statutory entities to consult with the Commissioner when setting the terms and conditions of employment for its chief executive, and enjoins the entity to ‘have regard to’ any recommendations made by the Commissioner.6 Previously, the Commissioner’s writ was confined to the Public Service in such matters. Further, the Act prohibits the payment of compensation to executives for loss of office, and their remuneration is now to be disclosed in the agency’s Annual Reports to Parliament. The new legislation also clarifies the reporting and accountability requirements of crown entities, with a strong emphasis on the production of annual ‘statements of intent’, which specify, inter alia, the entity’s functions and operations, and the impacts, outcomes and objectives that it seeks to achieve. The Act makes clear provision for the responsible minister in each case to be fully involved in the shaping of these statements. The power to ‘hire and fire’ will continue to be in the hands of the chief executives of these agencies, with direct accountability to the respective governing boards. 6 See Gregory (2003) regarding remuneration issues and controversies in the New Zealand public sector. 10 Managerial Alices in New Zealand’s political wonderland: the quest for collaboration Current state sector changes indicate that the pendulum of New Zealand state sector reform is currently swinging back in the direction of enhanced central power, away from ‘autonomization’. However, to use Pollitt’s (2004: 336) words, it is like a ‘pendulum swinging on a moving vehicle, as the political, technological and social landscape constantly shifts beneath the wheels’. A new resolution of the traditional bureaucratic paradox is now being sought, one which will supposedly find a new way forward between the imperatives of political and organizational control on the one hand, and cooperative purposeful achievement, on the other.7 The main strategic approaches used during three periods of New Zealand public administration and management are summarised (at the risk of oversimplification) in Table 1. Period Form of organization Means of securing compliance Rhetoric 1912 to mid1980s ‘Traditional’ bureaucracy Integrated hierarchies Prescribed authority; rules Bureaucratic; inefficient Mid1980s to late 1990s Private sector practices; quasimarkets; competition Separate and more autonomous agencies The above, plus financial incentives; contracts; performance management Results-oriented; freedom to manage; efficient; customer-driven; business-like Networked bureaucracy Increased central control over mainly decentralized services The above, plus managed collaborative interdependencies; strengthening public service ethos Service-users; partnerships; managing for outcomes; wholeof-government Late 1990s to present day Table 1: Three periods of New Zealand government administration and management 7 See C Talbot (2004) for a wider discussion of the paradoxical nature of human beings, but with particular reference to the paradoxes of governmental reorganization. He cites Norman’s (2003) examination of the paradoxes at the heart of the New Zealand state sector reforms. 11 The latest developments do not reflect a rejection of the principal components of either the State Sector Act or the Public Finance Act. The changes must be taken then as a form of ‘fine tuning’, which is to suggest that the problems they are intended to address are not major ones, and do not have their roots in any shortcomings in the foundational legislation. It is now simply a matter of enhancing the ability of the centre to steer, even though the ‘arm’s length’ principle, particularly in regard to crown entities, remains intact, and of striking a better pragmatic balance between the two conflicting imperatives. The new moves suggest that while ‘fragmentation’ and ‘siloization’ are problems, they are not overwhelming problems, and that the chosen remedy is proportionate to the size of the problem. In any case, what is termed ‘siloization’ is – like fragmentation – an age-old bureaucratic tendency, since it is impossible to have formal organizations without defined boundaries and in-bred cultures and collective mind-sets. In earlier times, in New Zealand as elsewhere, governments sought to enhance ‘coordination’ among its inherently self-absorbed agencies, by means of inter-departmental committees and such like, despite the strong tendencies of individual committee members to place the interests of their own organizations ahead of the collective good. The latest changes sit well with the contemporary fascination with ‘collaborative’ government, working ‘co-productively’ in partnership, and by way of both formal and informal networks, as much as directive coordination, in pursuit of governmental purposes. Indeed, the Review of the Centre itself promised ‘super networks’ to facilitate such cooperation, and ‘circuit-breakers’ to grapple more spontaneously, creatively and effectively with intractable problems of service delivery, particularly in areas of social policy. Alas, however, the trumpeted heralding of ‘super networks’ has not been followed by their actual appearance, and after two or three promising ‘circuit-breaker’ exercises that initiative has been put into abeyance. Why? The reasons are as yet to be fully disclosed, but it would hardly be surprising to learn that they have a lot to do with the fact that when conflicts arise between the need for organizational turf- 12 protection, on the one hand, and for inter-agency collaboration, on the other, chief executives may be relied upon to resolve them in favour of the former rather than the latter.8 And why would they not do so? Their own performances will be assessed primarily against their ability to deliver on the ‘output classes’ for which their particular organizations are responsible under the Public Finance Act. It is relatively easy to lead an organizational horse to the waters of collaboration but much harder to make it drink. Will the latest changes work? Such willingly collaborative enterprise depends on high levels of mutual trust, shared risk-taking, and good will among the top executives and managers of governmental agencies. If the economists are correct, it will also be encouraged by the use of effective incentives. But because of the Public Finance Act will continue to underpin a performance regime based on the need to produce outputs it is hard to see how exhortations to collaborate will override incentives which discourage, not encourage, such action. Moreover, if departmental chief executives are now to be held at least partially responsible for the co-production of policy outcomes, under the new ‘managing for outcomes’ philosophy, this will inevitably run counter to what has always been heralded as a central principle of New Zealand’s quest for clear accountability, namely, that individuals cannot be held accountable for outcomes over which they have little or no control.9 As Schick (2001: 16) has observed, ‘…New Zealand takes accountability seriously. It is not an afterthought or a byproduct, but the central thread of the New Zealand model’. To this end, the first generation reforms were intended to clarify roles and responsibilities, the better and more The State Services Commission (2004) reports that, ‘Originally a second round of Circuit Breakers was intended, however this has not proceeded…Selected Chief Executives were invited to nominate problems for a Circuit Breaking approach. Three possible problems were put up, but proved unsuitable.’ 8 9 According to Scott (2003: 163), one of the main designers of the first generation reforms, ‘Chief executives should be held liable for the job they are actually employed to do in a particular department facing particular challenges at a particular point in time, and not in terms of some generic statement of their responsibilities.’ 13 fairly to hold responsible parties to account for their performance. The desire for clear accountability is to be traded off against the need for the collaborative pursuit of policy outcomes. This pragmatic response is no bad thing, and at the very least it indicates a long overdue awareness that no amount of governmental reform anywhere, at any time, is capable of the simultaneous maximization of multiple and conflicting values. But it sits uneasily, to say the least, with the official claim that the Public Finance Act, which continues to be the solid foundation stone of an artificial outputs/outcomes bifurcation, is ‘fundamentally sound’ (State Services Commission, 2004a: 1). Such rhetoric is an example of what Brunsson (2002) calls ‘organizational hypocrisy’ – which includes the willingness of (and often the political need for) organization members to say one thing while doing another. The negative consequences of his bifurcation also play out in the ‘arm’s length’ relationship originally considered desirable (on the basis of public choice assumptions) between ministers and their departmental heads. While this in and of itself may indeed have allowed the political executive to focus more on its ‘steering’ role, in conceiving of ministers as (mere) ‘purchasers’ of outputs the Public Finance Act has overemphasized the operational side of government at the expense of the political. In so doing it has had the effect of impeding rather than enabling the political executive’s ability to steer. One consequence of this has been the increasingly important role played by political advisers in ministers’ offices. While there are certainly some advantages in this development, which was probably inevitable in any case, especially in an age of political ‘spin doctoring’, it reflects ministers’ desire to strengthen their grip on effective levers of political power. And it is also consistent with the fact that since the first generation reforms departmental chief executives have been appointed more for their managerial capacities than for their political and policy advisory skills.10 10 The norm now is for Public Service chief executives to complete a five-year initial term, followed by a three-year term. Hardly any have not had their contracts renewed, or been dismissed before the expiry of their first contract. New Zealand’s employment law renders any such termination very difficult. Thus, although ‘permanent tenure’ has been abolished, an eight-year term of office for a chief executive is tantamount to permanency. 14 The replacement of departmental heads’ permanent tenure by the introduction of fixed-term renewable contracts was intended to make top public servants more responsive to the political executive, yet without ‘politicizing’ the Public Service in ways that would threaten its professionalism, ‘neutrality’, and willingness to provide ministers with ‘free and frank’ advice. Whether or not such a balance has actually been achieved remains an open question (James, 2002). The results of surveys conducted by this author among Public Service chief executives, in 1995 and 2004, suggest that the politico-bureaucratic nexus has become increasingly reminiscent of the ‘Image I’ model depicted by Aberbach et al (1981).11 In other words, the policy-administration (management) split may well have become more institutionalized, consistent with a more ‘arm’s length’ relationship characterized by formal, contractualist, imperatives rather than high levels of mutually cooperative trust.12 Today, departmental heads see themselves not as one component of a symbiotic political partnership but as members of an executive class charged with the efficient operational management of the ‘machinery of government’. Over the past several years political blame-shifting games have become more publicly apparent. When things go wrong ministers are now more inclined to answer to Parliament by giving assurances that matters will be put right, while at the same time seeking to ensure that blame is sheeted as far from ministerial offices as is reasonably possible. This type of response is hardly new, and as always the working relationships among ministers and their departmental chief executives are strongly influenced by the individual personalities involved. However, the effects of blame-shifting games are exacerbated under a contractual/arm’s length situation, the more so when – as is the case in New Zealand – a much more fluid and The ‘Image I’ model is based on the classical politics-administration dichotomy, whereby politicians determine the shape of public policy and their officials occupy themselves with its ‘implementation’. The results of the author’s survey will form the basis of a forthcoming article, in preparation. See too Wilson and Barker (2003) regarding a similar situation in Britain. 11 12 Some departmental chief executives also hold, by virtue of their appointment to that role, statutory positions which require them to exercise independent professional judgment – for example, the Commissioner of Inland Revenue (who is also chief executive of the Inland Revenue Department). 15 uncertain political environment has emerged under the new Mixed Member Proportional electoral system, which reflected widespread popular concern over the dominance of the New Zealand political executive under the former First-Pastthe Post system (Gregory and Painter, 2003). Public servants today probably feel less confident of political support when their actions are exposed to critical public scrutiny, and staff morale suffers accordingly. And departmental heads now vie for their minister’s attention, partly in competition with ministerial political advisers, while ministers – concerned more with their political and policy agendas rather than with purchasing outputs and assessing executive performance – have sought to re-establish both strategic and tactical control over the ‘machinery of government’, and to ensure greater ‘alignment’ between agency and government objectives. This introduction of proportional representation electoral system has brought Parliament squarely back into the policymaking arena (Boston et al, 1999). It has also rendered much more uncertain and complex the political environment in which the heads of state sector organizations have to work. It has, in short, created a situation in which these executives require high levels of political nous and skill, to complement their managerial abilities. For these reasons the current quest for collaborative ‘joined-up’, or ‘whole-of-government’ strategies will be successful to the extent not only that the right structural incentives are in place (which they are not), but also to the degree that those who will be required to carry it through have the requisite skills, temperaments, and capacities (which they probably do not have). Departmental collaboration: the case of biosecurity Public administration scholarship has for many years understood the essentially political nature of the task of building organizational mission, among constituents both within and beyond the organization’s formal ‘boundaries’ (Long, 1949; Selznick, 1957; Lewis, 1980; Wilson, 1989; Carpenter, 2001). In this context, Wilson has defined autonomy as ‘relatively undisputed jurisdiction’ (1989: 183), no doubt mindful of the fact that if any public organization has full autonomy then its functions are probably trivial and innocuous. The quest for autonomy is a quest 16 for legitimacy, and it is usually unceasing, often fraught, and always essential. It does not depend solely or primarily on statutory empowerment but on the political capacities of those charged with shaping, promoting, and sustaining over time a sense of collective organizational purpose. It is not about management, it is about leadership. The concerns over turf protection displayed by many of the agencies involved in the recent establishment in the United States of the Department for Homeland Security illustrates in the grand manner the intensely political character of this endeavour. But despite these battles, which will continue to be played out intra-agency rather than inter-agency, it is scarcely conceivable that after 9/11 such a vitally important function could have been left to the separate agencies making up the Federal bureaucratic landscape in Washington, DC. New Zealand’s security problems are much less pressing than those of the United States. But they are nonetheless real and vitally important to the country’s economic and social well-being as a vulnerable trader in international markets. It may not be stretching a point too far to suggest that the New Zealand government’s biosecurity responsibilities are the rough equivalent of those faced by the American government in homeland protection. But in the two jurisdictions different organizational means have been adopted to undertake these two crucially important functions. Whereas in America the government has established a superbureaucracy in its attempt to secure effective collective action, in New Zealand positive biosecurity outcomes are expected to result from the collaborative willingness and capability of executives and managers located in largely autonomous departments with distinctly different primary missions. For many years biosecurity (the name itself has been adopted only very recently) was in the hands of a number of government departments and agencies, all responsible for different but related dimensions. This approach worked tolerably well, but provided inconsistent risk assessments and prioritization, inadequate analysis and dissemination of information, weak strategic capability, and ability to learn from past mistakes. Nor was there any single agency in control of the system. Structural ‘fragmentation’ in the system has been identified as a major problem, reflected in the inevitable games of bureaucratic turf-protection. 17 Now, in light of the growing complexity of biosecurity issues, more threats to New Zealand’s economic and environmental interests, and the need to ensure that the country fully meets its international biosecurity obligations the government has given the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) the lead role in implementing a new ‘whole-of-biosecurity’ approach, and responsibility for achieving a broad-based set of outcomes. However, these outcomes will be achieved (better to say, that these standards will be maintained?) only if MAF is able to secure effective collaboration among, in the first instance, four central government departments, all of which have very powerful, and largely independent, missions and responsibilities – MAF itself, the Ministry of Health, the Department of Conservation, and the Ministry of Fisheries. And all of which, under the Public Finance Act, have clear duties to produce a range of different outputs, with finance appropriated under four different Votes. It has been made clear that MAF will not directly control these activities, so the extent to which these disparate outputs can be transformed into consistently effective biosecurity outcomes will depend on its ability, for which the chief executive is to be held primarily accountable, to ‘actively seek opportunities for collaboration’ and ensure that any such collaboration is effective (Stocks, 2004: 4). The principal tool being used to this end consists of a set of memoranda of understanding between MAF and the other three organizations. One might venture to suggest that this new biosecurity strategy will continue to work tolerably well. But if and when something goes badly wrong, not only will there be the spectacle of dramatic blame-shifting games played out in the political arena, with public servants more unfairly exposed than ever before, but a new structural reorganisation will inevitably result. This will probably involve the creation of a new single-mission biosecurity agency.13 13 A former Labour cabinet minister, no longer in Parliament, recently observed publicly that, ‘Accepting ministerial responsibility is never popular, but it’s a dead duck with this government’ (The Dominion Post, 1 March 2005, p. B4.) His comments were made during a controversy over the activities of an educational crown entity. 18 More generally, it is unlikely that the current moves towards ‘whole-ofgovernment’ strategies for the achievement of policy outcomes can be optimised so long as the outputs/outcomes bifurcation in the Public Finance Act remains in place. This invention is the major flaw in the original architecture of state sector reform in New Zealand, an explicit statutory reinforcement of the goal-displacing tendencies inherent in all bureaucracies. It is little wonder that in their attempts to constructively resolve the fundamental paradox of bureaucracy no other countries have followed New Zealand’s lead down the outputs/outcomes path. This road to a rationalistic heaven of financial accountability is also beset by too many associated pitfalls. These include the separation of policy from operations; the dangerous divorce between the government as owner and as purchaser, as funder and provider; and at the political-bureaucratic nexus, the supplanting by a stilted legalistic contractualism of symbiotic relational contracts based on mutual trust.14 More palliative than cure? The main risk with the latest moves towards strengthening the centre in pursuit of ‘whole-of-government’ objectives is that they will turn out to be more palliative than curative. Instead of addressing head-on the distortions that arise out of the outputs/outcomes split the government has given the State Services Commissioner a wider mandate to enhance the influence of the centre across the state sector as a whole. However, this central sheriff has been ‘armed’ with statutory six-guns that may fire the odd real bullet but could well fire mostly blanks. The Commissioner’s new powers are as much persuasive as mandatory, and so their effectiveness will depend to a large extent on that official’s political abilities to engender the sort of cooperation from departmental and crown entity chief executives that will be needed to achieve a really meaningful impact. Certainly the Commissioner’s efforts will be reinforced by the force majeure that flows from the political executive’s commitment to reasserting the centre, but that will not be a constant in the re-centring equation. 14 The practical weaknesses of some of these conceptual inventions, especially the application of a quasi-market model, have been demonstrated most strongly in the provision of New Zealand public health services, where such reforms have now been largely rolled back (Gauld, 2001). 19 The current changes too reflect a shift in power balances between the central agencies. There is no doubt that the Treasury was the principal architect of the reforms of the 1980s and 90s, whose shape and character was dictated by that organization’s missionary focus on economic and financial management. Now, the SSC (whose functions were eviscerated by the first generation restructuring) is to be, potentially at least, a key player in the reassertion of the centre. This development will almost certainly enhance power struggles between these two central agencies, based primarily on the conflicting requirements for fiscal stringency, and the acknowledged need to develop and sustain state sector capability.15 Be that as it may, and looking at the overall picture, it is almost as if the government believes it can successfully repair what are major structural fissures by papering them over. The main reason why the outputs/outcomes split is central to the New Zealand state sector architecture is that, as Schick (2001: 16) has observed, ‘…more than any other country, New Zealand takes accountability seriously’. Too seriously, we might say. If an outputs-based accountability regime is considered to be indispensable because it ensures that the performance of ‘agents’ can be assessed against clearly specified and easily measured output targets then, as the New Zealand experience has confirmed, accountability is literally purchased at the cost of magnified goal displacement. On the other hand, if the current move towards ‘managing for outcomes’ is able to enhance interagency effectiveness, and ‘whole-of-government’ alignment, it will do so only by reducing ‘clear’ accountability, or – particularly when things go wrong – by unjustly imposing specific accountabilities where none are realistically available. Similarly too, the task allocated now to the State Services Commissioner to revivify a coherent and unifying ‘state sector ethos, or ‘Public Service ethos’, Newberry (2002: 326-7) argues that the Review of the Centre’s belief that the current public management system in New Zealand is ‘a reasonable platform to work from’ is ‘demonstrably wrong if the current government’s objective really is to “maintain and strengthen the State Sector.”’ She concludes that departmental ‘resource eroding processes’ were deliberately built into the government’s financial management system and ‘function in a manner highly consistent with a privatisation strategy.’ 15 20 involves strengthening organic dimensions that have been whittled away by the strongly mechanistic approach of the original reforms (Gregory, 1999; 2001). But again the question is: are the latest changes commensurate with the size and nature of the problem they are meant to overcome? Reorganizing the New Zealand state sector using means derived strongly from rational choice models of political and bureaucratic behaviour may to a very significant extent have created the difficulties they were intended to remove. And until there is more structural change that by its design implicitly challenges if not rejects these ‘rationalistic’ foundations then present-day reformers may find themselves whistling into the wind. When set against the background of questions like these it may seem that of equal if not more significance in the move back to more ‘joined-up’ governance has been some direct restructuring over the past three years, whereby the government has put back together that which was once rent asunder.16 It has amalgamated three Public Service organizations to form the current Ministry of Social Development, the country’s biggest government department, and has acted similarly, though not as extensively, in the areas of education, housing, justice, and transport. These restructurings united policy ministries with some of their relevant operational departments. In making these moves the government has implicitly deemed that any problems stemming from ‘provider capture’, as posited by the public choice theoretical tenets that underpinned the original reforms, have been less important than the need to reconnect, for their mutual benefit, policy ivory towers with street-level experience. Now, in the move to so-called ‘evidence-informed’ policymaking, it is being recognised that those working at the ‘coal-face’ have important experiential knowledge to offer. All this notwithstanding, the current shift back towards the centre is marked by an air of unreality similar to that which surrounded the original reforms. It is as if it were driven by people who still have a vested interest in the original statutory 16 Despite the comprehensive nature of the original reforms the total number of departments and ministries has remained relatively constant, around 36 to 40, during the past 15 years. There are about 70 Votes in the Parliamentary appropriations for the output classes that generated by Public Service departments. 21 architecture, and who are unwilling to acknowledge that the problems they are now trying to address result not from shortcomings in implementation but from fundamental flaws in the original design. The outputs/outcomes distinction is mirrored in the equally contrived purchaser/provider split, and is connected strongly to the use of quasi-markets for competitive service delivery, and to the purchasing agreements (between ministers and their chief executives), but which are not real contracts at all. Some major difficulties have emerged in this outsourcing regime, including allegations of fraudulent spending of public money, and a breakdown in relationships between departmental funders and nongovernment providers of social services (Report of the Community and Voluntary Sector Working Party, 2001; Controller and Auditor-General, 2003). There is a reluctance to acknowledge that experience virtually everywhere – including in New Zealand – shows that effective working relationships between ministers and their top bureaucrats depend not so much on formal contracts but on mutual trust, that good government depends more on political judgement and wisdom than on managerial measurement, and that any political executive will tend to see itself more as a mover and shaker of society than as a sterile purchaser of bureaucratic products. Why the large gap between political rhetoric and restorative action? The original reforms were theoretically informed, radical in their conception, comprehensive in scope, and authorized quickly by the opportunistic dominance of the political executive (Goldfinch, 2000; Aberbach and Christensen, 2001; Gregory 1998). For these reasons the New Zealand reforms, although widely studied and in some places even admired, have nowhere been emulated. By comparison, the latest changes are pragmatic, incremental, much more slowly put together, and – in keeping with the proportional Parliamentary system introduced in the mid-1990s – given a much more deliberative passage through the legislature.17 In fact, on the face of it, it is surprising that they have been so long in coming. 17 The two main parties of the right in Parliament, National and ACT (The Association of Consumers and Taxpayers), opposed parts of the new legislation, including the incorporation of the Fiscal Responsibility Act 1994 in the new Public Finance Act, the 22 When in opposition the Parliamentary Labour Party in the late 1990s was vociferously critical of aspects of the reformed public sector, especially when some highly controversial ‘golden handshakes’ were paid to some top governmental executives. It gave a clear message that on becoming the main party in a new coalition government it would take serious remedial action. It was even implied that several departmental heads would find their contracts terminated. So why has the action fallen quite a way short of the rhetoric? There are several, interconnected, reasons. There is the obvious reason that there are too many sunk costs in the system that emerged from the original reforms. Certainly there is an official view that the New Zealand state sector has experienced too much restructuring (Mallard, 2003). This argument is not inconsistent with a rational choice interpretation of how legislators in one era may seek to limit the options of their successors in another (Horn, 1995). Yet to understand why the foundations of the original structure are being left in place once has to dig a bit deeper. First, New Zealand’s state sector edifice, like New York’s Guggenheim Museum, may be subject to essentially cosmetic change, but like architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral design, it cannot be radically altered without destroying the original concept. The design is the building, as surely as the reforms are the system. Schick (2001: 3) rightly observes: ‘Unlike most countries which assemble reforms as if they were putting together lego blocks, in New Zealand, taking away a critical element, such as the output orientation, would strip the system of its magnificent conceptual architecture’. Secondly, the ideas that underpinned the original reforms have become strongly entrenched in the thinking of New Zealand policy elites. While state sector shortcomings may in fact be greater than the government seems willing to admit, because they result from fundamental design flaws, the original concepts and shift to multiple output classes, and the possible weakening of executive accountability to Parliament inherent in the move to managing for outcomes. 23 ideas have – in ideological and rhetorical terms – taken on a life of their own. The reality of the New Zealand governmental system has been increasingly socially constructed, and is that much stronger for it. If, for example, the words ‘outputs’ and ‘outcomes’ were once absent from the lexicon of institutional design, and meaningless in the discourse of the designers, today their meaning is not only taken for granted but is solidly concrete in its effects. Thirdly, the political impact of the neo-liberal reforms of the 1980s and 90s has endured in New Zealand, where the centre has shifted to the right, largely because of the susceptibility of the deregulated New Zealand economy to the impact of globalization and the portability of international capital.18 A Labour or Labour-led government in New Zealand has only once before achieved three or more consecutive terms in office, and the current government is now eyeing this possibility – indeed probability – leading up to the 2005 general election. The original reforms were based on a neo-liberal belief in the need to reduce the ability of the state to ‘intervene’ in the social and economic marketplace. The state sector legislation passed at the end of 2004 indicates no resolve on the part of a centreleft government to radically reverse that intention. Instead, fully consistent with its wider quest for the ‘third way’, it has settled in state sector management for what it feels is a more comfortable balance between its powers of control, on the one hand, and its exposure to political risk, on the other. The quest for this new balance is well illustrated in the case of the Building Industry Authority (BIA), a crown entity whose main function of regulating building construction standards was hived off from departmental embrace in the early 1990s. Three years ago political blame-shifting games ensued after it had become clear that standards of housing construction had declined badly, leaving thousands of New Zealanders living in homes inadequately insulated against the effects of the weather. In 2004 the functions of the BIA were absorbed back into a newly created Department of Building and Housing, under full ministerial control. 18 For example, in the 1970s, after two decades of full employment, an unemployment rate of 4.5% in New Zealand would have been politically disastrous. Today, it is a source of great political comfort. 24 Finally, Pollitt (2004: 330) rightly notes that, ‘…the grass on the other side is always greener. We choose one particular way of organizing…and then, as we experience its character, we begin to see the advantages of its opposite’. His invocation of Hood’s (1998: 11) anthropological view of ‘mutual antagonism among opposites’, is well supported by current evidence of New Zealand state sector reform, especially regarding the move by the centre to create and grasp more effective levers of control over crown entities. Yet such shifts do not occur in a political vacuum, as if guided by a proverbial ‘invisible hand’. The wider political context in which this shift from autonomization is occurring in New Zealand also says something about the relationship between theory and practice in policymaking on state sector change. Faith and works: learning from the New Zealand experience The New Zealand experience of state sector reform in the years since the mid1980s is interesting, not just in its own terms but also as a study of the relationship between theory and practice in public policymaking. The extent to which the architects of the original reforms eschewed practical experience in favour of abstract and largely untested theoretical ideas should not be overstated, but it is generally accepted that as economists they were persuaded by the elegance and parsimony of rational choice approaches rather than by the seemingly more messy and ambiguous old institutionalism characteristic of mainstream public administration scholarship. There was a direct correlation, in fact, between the extent to which the original reforms were shaped by a largely coherent body of theory drawn from the rational choice stable, on the one hand, and their radical and comprehensive scope, on the other. In a discussion of C E Lindblom’s enduring contribution to public policy theory the author has elsewhere argued that there is no necessary relationship between these two variables, and that the crucial element in determining the scope of policy change is not so much the degree of formal theoretical knowledge which informs the changes as it is the availability of political opportunity to adopt them (Gregory, 1989). 25 In the case of the state sector reforms in New Zealand in the mid to late 1980s both factors coalesced. By contrast, today the opposite situation prevails. The latest changes are important if not radical, are pragmatically rather than theoretically inspired, and their lengthy gestation (over the best part of three years) stands in sharp relief to the ‘blitzkrieg’ approach which impelled the earlier ones, and reflects – as discussed above – the political aversion to following through on what might once have promised to be a new round of major structural change. New Zealand state sector reform over the past fifteen years comes reasonably close to exemplifying Etzioni’s (1967) ‘mixed-scanning’ model of public policymaking, whereby a radically comprehensive policy change or initiative is followed by more incremental changes to it, over time. However, Etzioni’s framework proposes little if anything about the relationship between the use of theoretical knowledge in shaping policy and the scope of policy change. The New Zealand experience, on the other hand, suggests that a priori theoretical interpretations tend to take on a life of their own, as it were, by actually fostering – in ways reminiscent of the ‘Hawthorne effect’ – the behaviour that they were purportedly describing scientifically. The original reformers believed that public choice and agency theories were theoretical tools that enabled them to solve perceived problems such as ‘provider capture’ of the political executive by egoistically self-interested bureaucrats who were unresponsive to the will of the elected government of the day. Yet fifteen years on an assiduous researcher could find as much if not more evidence to support a thesis that these theoretical dimensions of the reforms addressed a ‘problem’ that – like the Sir Humphrey Appleby of television’s Yes, [Prime] Minister – was a caricature of reality rather than an accurate description of it. Any such researcher could also garner more than enough empirical evidence to support an argument that these theoretical nostrums drawn from the reformers’ tool-bag became instrumental in actually shaping rather than countering the sort of behaviour by government officials that they aimed to prevent. Arguably, the first generation reforms produced a type of official that they were intended to get rid of, but who did not really exist in the first place. It is not just that the radical 26 structural changes authored by the original legislation produced the unintended, but easily foreseeable, consequence of too much fragmentation, diminishing the centre’s capacity to steer, and thus resulting in the latest round of reforms. Even more interesting from the perspective of those who seek to understand better the relationship between theory and practice in state sector reform, there is apparent a remarkable unwillingness for the current reformers to reflect on the validity of the original theoretical instruments (Gregory, 2003a). Instead, the original designs continue to be publicly regarded as sound, even if the problems they gave rise to and the latest responses to those shortcomings, suggest otherwise. In the Orwellian language of the technocratic successors to the original architects, a ‘major rewrite’ of the Public Finance Act does not constitute a ‘major reform’. Most if not all of the original architects have long since moved on to bigger and better career paths, leaving their successors to deal with the impact of their misplaced belief in the appropriateness and efficacy of rational choice theoretical tools. The fact that their successors remain solidly committed to similar ideas, in the face of evidence that might induce in many others a healthy scepticism of the assumptions which underpin them, testifies to the extent to which ideas can become so strongly institutionalised, and normalized, that they become impervious to critical reflection. This can sometimes be readily explained by the understandable desire of influential people to protect their careers and reputations, and their capacity to do so when they themselves remain as significant gatekeepers of what constitutes ‘informed’ opinion. But even when they themselves have departed the scene and their direct personal influence has greatly diminished, the boundaries within which ‘informed opinion’ is defined remain intact, largely immune from the challenges not only of alternative theoretical paradigms but also of practical experience. To reiterate, the negative impact of ‘fragmentation’ and siloization’, the diminished capacity of the centre to steer according to ‘whole of government’ imperatives, the threat to longer-term public service capability, the endemic goaldisplacement fostered by the outputs/outcomes bifurcation and its associated performance and accountability apparatus, to mention just some consequences of the first generation reforms, are all interpreted as relatively minor shortcomings of 27 designs which are believed to be ‘fundamentally sound’. It is bad enough that at the practical level such a Panglossian mindset diminishes the significance of these difficulties, it is even worse that the theoretical frameworks from which they were derived are not believed to be worthy of reconsideration at the same time as they – albeit now tacitly rather than explicitly – dominate the thinking of contemporary technocrats. It is not that the mutually constitutive double-loop of theory and practice has become disconnected at its nexus point. If that were so then theoretical reflection would be totally insulated from practical experience, while the latter would be driven by purely pragmatic action. Instead, what is occurring is reminiscent of J M Keynes’ much-quoted observation that today’s practical men act as if driven by the theories of long-dead academic scribblers. As Hay (2004: 60) argues, ‘In so far, then, as the predictions of rational choice theory or neo-classical economics conform to political and economic practice, it may well be because political and economic actors have internalized precisely such theories, incorporating them within their modes of calculation and practice’. It is telling that New Zealand’s first generation state sector reforms included a widely acclaimed move to institutionalize the political independence of its central bank, through the instrument of the Reserve Bank Act 1989. This legislation makes the organization amongst the most politically independent central banks in any western country. Its independence is founded firmly on the monetarist tenet that a high degree of certain, manifest, credible, and continuing political independence is essential if the bank is to be able to keep inflation at prescribed low levels. Certainly, the theory seems to have worked in New Zealand’s case: from high levels in the 1980s inflation in New Zealand since then has been of the order of three percent per annum. But what causes what? Does central bank independence ‘cause’ low inflation, or are both low inflation and central bank independence both a function of some other factor – for example, the political power of so-called ‘financial markets’, which is an economic euphemism, in effect, for rich people and institutions (Gregory, 1996)? As Watson (2002: 188) argues, ‘…there can be no simple one-to-one link between central bank policy and 28 inflation performance. Yet the whole rationale for increasing [central bank independence] is based on the assumption of such a link’.19 Among most monetarist theorists, in New Zealand as elsewhere, beliefs about the need for high levels of central bank independence as a means of maintaining financial stability have become ‘institutionalized “common sense”’ (Watson, 2002: 192, citing Mayer, 1999). There is little inclination to accept alternative views, not so much because their falsity can be convincingly demonstrated but because the theory to which the monetarists resolutely subscribe has become sacrosanct – an article of faith rather than of science. It is, nevertheless, an orthodoxy that has real political effect (governments are warned against adopting policy options that would make financial markets nervous, but seldom against those which may make poor people nervous). What is true in regard to reflection on the theoretical underpinnings of New Zealand’s Reserve Bank is also true of the country’s wider state sector reforms. There is none. This fact may only be of largely academic concern were it not the case that such unreflective commitment to theoretical tenets, to the extent that they become strongly institutionalized, actually shape the behaviour that they purport to describe. In other words, the New Zealand experience of state sector reform, driven by rational choice theoretical constructions, raises important questions about the ongoing relationship between science and politics (Gregory, 1998). There is no space to pursue these here, except to say that what has been occurring in New Zealand provides ample evidence in support of Hay’s argument: Used judiciously and cautiously for a series of carefully specified purposes it [rational choice theory] is a potentially powerful weapon in the armoury of the critical policy analyst. Yet offered – as it so often is – as a universal theory of (political) conduct, it prejudges the question of rationality, commits itself to assumptions whose implausibility many of its exponents freely admit, and renders redundant the critical question of the conditions under which the rationality assumption is most likely to hold…there is a clear danger of the self-fulfilling prophecy in such a totalizing meta19 See, for example, Posen (1993, 1995) for a cross-national analysis of central bank independence which challenges this link. 29 narrative. For, arguably, rational choice models correspond most closely to the reality they purportedly represent where they ‘describe’ the behaviour of actors who have internalized rational choice assumptions (2004: 40). As Hay suggests, the main reason why the architects of both first and second generation state sector reforms seem impervious to alternative explanations and interpretations of political and bureaucratic behaviour is to be found in their educational backgrounds. In his words, ‘That models predicated upon rational choice assumptions seem to have explanatory potential within economic systems, may reflect nothing other than the prevalence of rational choice assumptions in the mindsets of public policy-makers thoroughly immersed in neo-classical economics since their undergraduate days’ (2004: 42). It is hardly surprising that 15 years after rational choice instrumentalism enjoyed its heyday in New Zealand public policymaking there has now emerged the practical need to re-establish the status of the core public service, indeed the wider state services, as a collective ‘whole-of-government’ entity, with a reinvigorated ethos of public service and institutional capability. The drive to ‘autonomize’ state agencies has now to be supplanted by the urgent need to integrate them in a way that will foster collaborative rather than competitive endeavour. The current response is surely pragmatically rather than theoretically driven, but it is a pragmatism that as yet remains too securely locked within the theoretical framework that shaped the changes of the 1980s. Conclusion: travelling forward while looking back The autonomization of state agencies in New Zealand was a central feature of the radical state sector reforms of the 1980s and early 90s, which were driven essentially by a rational choice theoretical paradigm. This approach was fully consistent with the neo-liberal political agenda that held sway in New Zealand at that time, and which was concerned to reduce the scope of state involvement in the economy and to ‘depoliticize’, in the pursuit of more efficient management, a whole variety of governmental functions (Kelsey, 1995; Larner, 2000). The architects of the reforms were strongly persuaded by the central tenets of public choice and agency theory in reshaping the state. The latest, second generation 30 reforms, are intended to redress structural problems that were unintended consequences of those changes, in order to enhance governmental capacity for collaborative endeavour among its agencies. These current developments are pragmatic responses intended to enhance the centre’s steering capacity, to render state agencies more responsive to the political will of the government of the day, and to increase its control of real and potential political risk. The original reforms attracted world-wide attention, not only because of their scope but also because of the apparent coherence and elegance of their theoretical foundations. Never before in New Zealand, and probably nowhere else among the western democracies, had so many radical structural changes been generated on the back of so much elegant theory, in turn derived from so few unexamined assumptions. If New Zealand was seen as a showcase heralding a new age of ‘scientific’ state sector reform then, perhaps unsurprisingly, it has proved to be a largely false dawn. Experience confirms what commonsense says: that in all areas of public policymaking, but especially in policymaking which addresses the structure and role governmental organizations, there can be no apolitical fix. The real challenge is not to be able to find certainty in theoretical prescriptions of any kind, but to be able to ensure that all theoretical propositions remain subject to the test of political experience, the better to reflect on them, revise them, and intelligently transform them. A positivist scientific approach was adopted by the original architects, at that time located in bureaucratic ivory towers insulated from the hurly-burly of adversarial politics, and buoyed by their belief that their theoretical certainties were essentially scientific rather than ideological. Today, policymaking for New Zealand state sector reform is less technocratic in character, more politically contestable, yet still strongly constrained by the legacy of once dominant neo-liberal beliefs. When those ideas were in their ascendancy in New Zealand, in the late 1980s, the corporatization of government trading functions was to be a half-way house on the road to full privatization (a road that indeed became well travelled). It remains to be seen whether, analogously, the latest developments in New Zealand state sector reform – attempting pragmatically to rejoin what was once rent asunder – will turn out to be a midway 31 point on the way to achieving the enduring collaborative capacity that is now sought. _________________________________________________________ REFERENCES Aberbach, J and Christensen, T (2001) Radical Reform in New Zealand: Crisis, Windows of Opportunity, and Rational Actors, Public Administration, 79, 2, pp. 403-422. Aberbach, J, Putnam, R, and Rockman, B (1981) Bureaucrats and Politicians in Western Democracies, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. Boston J, Martin J, Pallot J, and Walsh, P (1996) Public Management: The New Zealand Model Auckland: Oxford University Press. Boston, J, Levine, S, McLeay, E, and Roberts, N (1999) (eds) Electoral and Constitutional Change in New Zealand: An MMP Source Book, Palmerston North, NZ: The Dunmore Press. Brunsson, N (2002) The Organization of Hypocrisy: Talk, Decisions, Actions in Organizations, 2nd edn, Norway: Abstrackt/Liber. Carpenter, D P (2001) The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862-1928, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Controller and Auditor-General (2003) Inquiry Into Public Funding of Organisations Associated With Donna Awatere Huata MP, November. See http://www.oag.govt.nz Etzioni, A (1967) Mixed-Scanning: A ‘Third’ Approach to Decision Making, Public Administration Review, 27, 5, pp. 385-392. Gauld, R (2001) Revolving Doors: New Zealand’s Health Reforms, Wellington NZ: Institute of Policy Studies and Health Services Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington. Goldfinch, S (2000) Remaking Australian and New Zealand Economic Policy, Wellington: Victoria University Press. Gregory, R (1989) Political Rationality or ‘Incrementalism’? Charles E. Lindblom’s Enduring Contribution to Public Policymaking Theory, Policy and Politics, 17, 2, April, pp. 139-153. 32 Gregory, R (1996) Reserve Bank Independence, Political Responsibility, and the Goals of Anti-Democratic Policy: A Political ‘Cri de Coeur’ in Response to an Economist’s Perspective, Working Paper 11/96, Graduate School of Business and Public Management, Victoria University of Wellington. Gregory R (1998) New Zealand as the ‘New Atlantis’: A Case Study in Technocracy, Canberra Bulletin of Public Administration, 90, December, pp. 107112. Gregory, R (1999) Social Capital Theory and Administrative Reform: Maintaining Ethical Probity in Public Service, Public Administration Review, 59, 1, pp. 63-75. Gregory, R (2001) Transforming Governmental Culture: A Sceptical View of New Public Management in New Zealand, in T Christensen and P Laegreid (eds) New Public Management: The Transformation of Ideas and Practice, Aldershot UK, Ashgate Publishing. Gregory, R (2002) Governmental Corruption in New Zealand: A View Through Nelson’s Telescope? Asian Journal of Political Science, 10, 1, June, pp. 17-36. Gregory, R (2003) New Zealand: The End of Egalitarianism? in C Hood and B G Peters (eds) Reward for High Public Office: Asian and Pacific Rim States, London: Routledge. Gregory, R (2003a) All the King’s Horses and All the King’s Men: Putting New Zealand’s Public Sector Together Again, International Public Management Review (e-journal), 4, 2, pp. 41-58. Gregory, R and Painter, M (2003) Parliamentary Select Committees and Public Management Reform in Australasia: New Games or Variations on an Old Theme? Canberra Bulletin of Public Administration, 106, February, pp. 63-71. Hay, C (2004) Theory, Stylized Heuristic or Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? The Status of Rational Choice Theory in Public Administration, Public Administration, 82, 1, pp. 39-62. Hood, C (1998) The Art of the State: Culture, Rhetoric and Public Management, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Horn, M (1995) The Political Economy of Public Administration: Institutional Choice in the Public Sector, New York: Cambridge University Press. James, C (2002) The Tie That Binds: The Relationship Between Ministers and Chief Executives, Wellington: Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington. Kay, J (2003) Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets – Why Some Nations Are Rich But Most Remain Poor, London: HarperBusiness. 33 Kelsey, J (1995) The New Zealand Experiment: A World Model for Structural Adjustment? Auckland: Auckland University Press/Bridget Williams Books. Lewis, E (1980) Public Entrepreneurship: Toward a Theory of Bureaucratic Political Power, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Larner, W (2000) Neo-Liberalism: Policy, Ideology and Governmentality, Studies in Political Economy, 63, pp. 5-25. Long, N (1949) Power and Administration, Public Administration Review, 9, 4, pp. 257-264. Mallard, T (2003) Ministerial Address to the Annual General Meeting of the New Zealand Institute of Public Administration, ‘Progress on Public Management Initiatives’, Public Sector, 26, 2, pp. 23-26. Mayer, T (1999) Monetary Policy and the Great Inflation in the United States, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. New Zealand Institute of Public Administration (2005) The New State Sector Legislation, seminar presentation, 16 February 2005. Available on http://www.ipanz.org.nz Newberry, S (2002) Intended or Unintended Consequences? Resource Erosion in New Zealand’s Government Departments, Financial Accountability and Management, 18, 4, pp. 309-330. Norman, R (2003) Obedient Servants: Management Freedoms and Accountabilities in the New Zealand Public Sector, Wellington: Victoria University Press. Office of Public Services Reform (2002) Better Government Services: Executive Agencies in the 21st Century, London: Office of Public Service Reform. Pollitt, C (2004) Theoretical Overview, in C Pollitt and C Talbot (eds) Unbundled Government: A Critical Analysis of the Global Trend to Agencies, Quangos and Contractualisation, New York: Routledge. Posen, A (1993) Why Central Bank Independence Does Not Cause Low Inflation: There is No Institutional Fix for Politics, in R O’Brien (ed) Finance and the International Economy, 7 Oxford: Oxford University Press. Posen, A (1995) Declarations Are Not Enough: Financial Sector Sources of Central Bank Independence, in B Bernanke and J Rotemberg (eds) NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1995, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, pp. 253-274. Report of the Community and Voluntary Sector Working Party (2001) Communities and Government: Potential for Partnership, Wellington: Ministry of Social Policy. 34 Schick, A (2001) Reflections on the New Zealand Model, Notes Based on a Lecture at the New Zealand Treasury, August. Scott, G (2001) Public Management in New Zealand: Lessons and Challenges, Wellington: New Zealand Business Roundtable. Selznick, P (1957) Leadership in Administration, New York: Harper and Row. State Services Commission (2004) Update: Integrated Service Delivery Programme, at http://www.ssc.govt.nz State Services Commission (2004a) Public Finance (State Sector Management) Bill Now Enacted, at http://www.ssc.govt.nz Stocks, P (2004) Which Agencies Will Do What? Biosecurity Issue, 55, 1 November. Talbot, C (2004) The Paradoxical Primate, Exeter: Imprint Academic. Watson, M (2002) The Institutional Paradoxes of Monetary Orthodoxy: Reflections on the Political Economy of Central Bank Independence, Review of International Political Economy, 9, 1, pp. 183-196. Wilson, G and Barker, A (2003) Bureaucrats and Politicians in Britain, Governance, 16, 3, pp. 349-372. Wilson, J (1989) Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do and Why They Do It, New York: Basic Books. ___________________________________________________________