Market Lambs - Animal Sciences - University of Wisconsin

advertisement

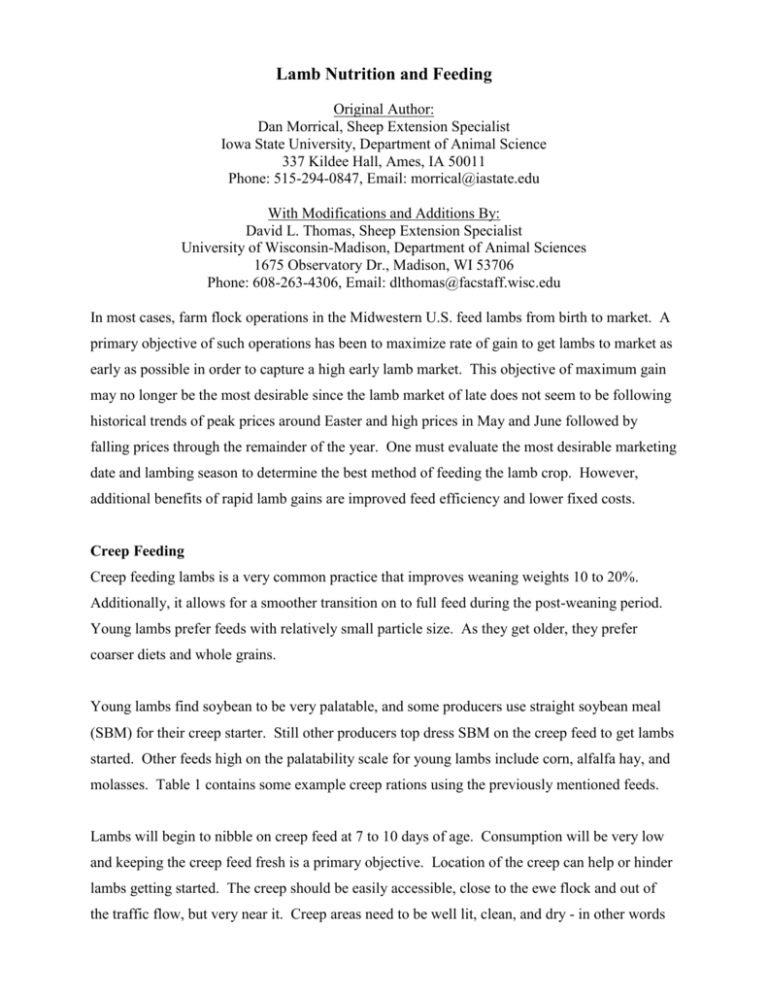

Lamb Nutrition and Feeding Original Author: Dan Morrical, Sheep Extension Specialist Iowa State University, Department of Animal Science 337 Kildee Hall, Ames, IA 50011 Phone: 515-294-0847, Email: morrical@iastate.edu With Modifications and Additions By: David L. Thomas, Sheep Extension Specialist University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Animal Sciences 1675 Observatory Dr., Madison, WI 53706 Phone: 608-263-4306, Email: dlthomas@facstaff.wisc.edu In most cases, farm flock operations in the Midwestern U.S. feed lambs from birth to market. A primary objective of such operations has been to maximize rate of gain to get lambs to market as early as possible in order to capture a high early lamb market. This objective of maximum gain may no longer be the most desirable since the lamb market of late does not seem to be following historical trends of peak prices around Easter and high prices in May and June followed by falling prices through the remainder of the year. One must evaluate the most desirable marketing date and lambing season to determine the best method of feeding the lamb crop. However, additional benefits of rapid lamb gains are improved feed efficiency and lower fixed costs. Creep Feeding Creep feeding lambs is a very common practice that improves weaning weights 10 to 20%. Additionally, it allows for a smoother transition on to full feed during the post-weaning period. Young lambs prefer feeds with relatively small particle size. As they get older, they prefer coarser diets and whole grains. Young lambs find soybean to be very palatable, and some producers use straight soybean meal (SBM) for their creep starter. Still other producers top dress SBM on the creep feed to get lambs started. Other feeds high on the palatability scale for young lambs include corn, alfalfa hay, and molasses. Table 1 contains some example creep rations using the previously mentioned feeds. Lambs will begin to nibble on creep feed at 7 to 10 days of age. Consumption will be very low and keeping the creep feed fresh is a primary objective. Location of the creep can help or hinder lambs getting started. The creep should be easily accessible, close to the ewe flock and out of the traffic flow, but very near it. Creep areas need to be well lit, clean, and dry - in other words one of the most comfortable locations in the barn. Creep areas serve another important function in that they provide a sanctuary for lambs to get away from the ewe flock. As lambs grow, creep gates need to be adjusted to allow lamb access yet continue to prevent ewe access. This is no easy task. Feeders used in the creep area need to be designed such that lambs cannot stand in the feeders to reduce exposure to coccidia. As lambs approach weaning age, a management decision must be made on whether to switch lambs to the post-weaning ration before or after weaning. Weaning age directly influences this decision. With lambs weaned at greater than 60 days of age, the switch can be made preweaning. However, with lambs weaned at younger ages, the change needs to occur after weaning. An additional factor to consider is the cost of the creep ration compared to the grower/finisher ration. Growing and Finishing Diets Many producers feed lambs the same diet from weaning to market. This is generally done for convenience, and lambs will grow well if fed the growing diet throughout. However, grower diets should have 16 to 18% protein (as a % of dry matter) (Table 1), and lambs over 70 to 85 pounds do not need this much protein (Table 2). Therefore, switching to a finishing diet (Table 1) that is lower in protein when lambs are approximately 85 pounds can reduce feed costs. Complete mixed diets can be formulated from several ingredients (Table 1) or purchased from commercial feed companies. Feeding whole shelled corn in combination with a high protein pellet that also contains minerals and vitamins is generally more cost effective than feeding a complete mixed diet. Many commercial feed companies sell a protein pellet of approximately 34% protein, and rations utilizing such pellets are presented in Table 1. Iowa State University has developed a 42% protein pellet (Table 3), and its use in rations is presented in Table 1. It is important that the corn in these corn/high protein pellet diets is not processed. Hay is generally not fed with these diets, and the whole shelled corn provides the “scratch” factor necessary for proper rumen function. Feed management is very important on these high concentrate growing and finishing rations. Animals must never be without feed if on self-feeders or never be without feed for a long period of time (several hours) if hand fed. Lambs fed a high concentrate diet after being without feed 2 for a several hour period will overeat and consume a very large quantity of grain in a short period of time. This can result in a rapid drop in rumen pH (acidosis), founder, and death. Self Feeding Versus Hand Feeding There are advantages and disadvantages to both systems. The biggest disadvantage of selffeeding is that monitoring lamb health is more difficult. This is because all lambs are not actively eating at the same time and requires the shepherd to move through the pen(s) observing lambs for signs of illness. However, hand feeding requires more bunk space. Unless the ewe flock is dry-lotted, feeders previously used to feed ewes during pregnancy and lactation can be used by hand-fed lambs. Hand-fed lambs require 9 to 15 inches of bunk space per head. The higher space requirements are for heavy lambs (>120 pounds) or lambs in full fleece. Hand feeding does require more labor and should be done in two equal feedings each day. Ideally, feeding times should be similar from day to day as lambs become accustomed to a specific feeding schedule. An additional advantage of hand feeding is the incorporation of hay into the ration. At times hay can be a very economical ingredient to include in the ration at 10 to 20 percent of the total ration. Cost Control Measures Generally when discussing feed cost of gain, one first considers the cost of the ration as the biggest factor. Ration costs are currently very low and furthermore should stay low in future due to incredibly high inventories of grains. Even today with our cheap grain prices, there may be some byproduct feeds that can cheapen the ration even further. An example might be dry corn gluten feed. It is important to shop around for under-utilized (cheap) feed resources in the area. Protein requirements (Table 2) of native farm flock lambs are high because they are generally sired by Suffolk or Hampshire rams and have greater average daily gains than white-faced lambs common in the West. Higher protein levels will increase the cost of the diets. As lambs reach heavier weights, their protein requirements decrease (Table 2) so frequently adjusting protein content downward throughout the feeding period can reduce feed costs. An additional means of reducing protein costs is to investigate cooperative purchasing of commercially available protein supplements or ordering a custom protein supplement. In most cases, a minimum of three tons is required for custom orders. 3 The custom protein supplement formulation used at the Iowa State University McNay Research Farm along with feeding directions is presented in Table 3. Incorporating alfalfa hay into the finishing ration may also provide a cheaper protein source. Feeding rations with more than 10% hay will result in slower growth rates and poorer feed conversions. This may result in a higher feed cost of gain even though the ration cost per ton is lower. Other means of reducing lamb feeding costs is timely marketing of finished lambs. It takes more feed to produce a pound of fat than it does to produce a pound of lean. As lambs reach market weight they become much less efficient and feed cost of gain increases dramatically. Ewe and wether lambs should be marketed at 65 to 75% of their potential mature weight in order to produce a market lamb with desirable feed efficiency and fat cover (Yield Grade 2 or 3 carcass). Another way to improve growth efficiency is to use large-framed, heavy-weight terminal sires because their offspring have better feed efficiency to the same weight than small- or mediumframed lambs. Table 4 presents market weights at which ewe and wether lambs produced from parents of different sizes are expected to produce Yield Grade 2 carcasses (.16 to .25 inches of fat over the loin at the 12th-13th rib). The target weights in Table 4 should be increased by 10 to 20 pounds if the goal is Yield Grade 3 carcasses (.26 to .35 inches of fat over the loin at the 12th13th rib). Lamb death loss during the feeding period also impacts feed cost of gain. Preventative health programs addressing health problems that have occurred in the past is money well spent. The last area that is not often discussed relative to controlling feed cost of gain is to minimize waste. With appropriately constructed feeders, this should not be a problem. Feed spoilage due to poor storage or sloppy transport from storage to feeders can increase cost of gain 2, 5 or even 10 percent. Common Nutritional Disorders and Diseases White Muscle Disease Selenium and vitamin E are two nutrients that must be incorporated into creep rations. White muscle or stiff lamb disease is the common name referring to deficiencies of either/or both selenium and vitamin E. Soils throughout much of the Midwest and, therefore, feedstuffs grown in the Midwest tend to be deficient in selenium. All lamb rations should be fortified with at least 4 .18 grams of selenium and 15,000 international units (IU) of vitamin E per ton of complete feed. One quickly realizes that .18 grams is a very small (.000397 lb.) amount to incorporate into a ton of feed. Therefore, accurate scales and thorough mixing are critical since 2 parts per million (ppm) can be toxic (.0044 pounds). Commercial mineral mixes specifically formulated for sheep almost always contain added selenium, and mineral/vitamin premixes used in the formulation of lamb diets and commercial complete mixed lamb feeds almost always have added selenium and vitamin E. However, feed labels should always be checked to make sure that selenium and vitamin E, and the minerals and vitamins discussed later, are present in the desired quantity. Creep consumption by young lambs may not provide adequate selenium or vitamin E intake relative to their requirements. Many sheep operations routinely administer injectable selenium and vitamin E to lambs as additional insurance in combating a deficiency. Two important points are critical to remember, one being that vitamin E stores in the body are very low and secondly, serum vitamin E levels drop very rapidly to pre-injection levels (5 to 8 days). Lastly, very little vitamin E crosses the placenta so colostrum or an injection are the lamb’s only means of getting vitamin E. Copper Toxicity Sheep are very efficient at storing ingested copper. Excess copper is stored in the liver. When a copper-loaded liver dumps its copper into the blood stream, the copper causes destruction of the red blood cells and death quickly follows. Copper is an essential mineral and all feeds contain some copper. Cooper also is a contaminate in sources of other minerals, so mineral mixes with no major copper supplement will still have trace amounts of copper. It is important, however, that copper not be added to mineral mixes or feeds for sheep. Copper is a common additive to swine and poultry feeds and mineral so diets formulated for these species should not be fed to sheep, and contamination of sheep diets with poultry and swine diets in commercial mills must be avoided. Common feedstuffs for sheep (e.g., corn, soybean meal, hay) do not contain toxic levels of copper. However, even “normal” levels of copper can cause copper toxicity if the level of molybdenum in the diet is very low. If lambs have died from copper toxicity and copper levels 5 in the feed and mineral are normal, feedstuffs should be analyzed for molybdenum level. Some byproduct feeds also may contain high levels of copper (> 30 ppm) and if used, should not constitute a high proportion of the diet. Urinary Calculi (UC) As previously stated, maximum gain is generally the objective when feeding lambs. This requires the feeding of high concentrate diets that result in a poor calcium to phosphorous ratio (less calcium than phosphorous). This is due to grain being very low (< .05%) in calcium. All high grain rations should be fortified with calcium by adding 1 to 3% limestone to the ration. Additional methods of preventing UC include adding 10 pounds of salt and 6 to10 pounds of ammonium chloride or sulfate per ton of ration. Clean, fresh water sources reduce UC through increased water intake and urine output that serves to flush the urinary tract. An additional benefit with increased water intake is a corresponding increase in intake and performance. During cold weather it is critical to provide a warmed water source to encourage consumption. Polioencephalomacia (PEM) Polioencephalomacia is a thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency that usually occurs following a digestive disorder. Symptoms of PEM are neurological with staggers, blindness, and convulsions being the most common. Lambs will eventually go down flat on their side, paddle, and arch their head over their back. Examples of situations that might create PEM include poor communications that results in a double feeding, lambs being without feed for several hours and then gorging on feed when fed, or lambs escaping from their feeding pen and having free access to stored feed. The best indicator of PEM is the response to thiamine injections. One should see rapid responses. However, if digestive upsets created the problem, supplemental thiamine injections may need to be continued for several days until the digestive health of the animal has returned to normal, and it is eating aggressively. Coccidiosis Most commercially available lamb feeds contain Bovatec (Roche), an ionophore that improves feed efficiency (3 to 5%) and controls coccidiosis. The Roche technical manual indicates that lambs should consume 15 to 80 mg of Bovatec per day. Consumption of approximately one 6 pound of creep ration is necessary in order to get this amount of Bovatec. In very young lambs, this level of intake is impossible due to their low bodyweight. In most situations, prevention of coccidiosis in very young lambs requires strict sanitation and management along with a much more aggressive strategy to increase Bovatec intake. One must note that FDA allows the maximum level of Bovatec incorporation into the feed at 30 grams per ton. Enterotoxemia (Overeating) Overeating (OE) is one of the most common causes of death in feedlot lambs. Management inputs to minimize OE include gradual ration changes, vaccination programs, and feeding 20 grams per ton of oxytetracyline (OTC) or chloratetracycline (CTC). Neither antibiotic is cleared to be fed with Bovatec. Lambs being fed on self-feeders must always have feed available once they are adapted to self-feeders. Flocks using hand feeding should monitor daily consumption and adjust feed offered so that lambs are just slightly hungry. In farm flock operations, annual boosters to ewes during late gestation along with lamb vaccinations at 3 and 6 weeks of age provides the best possible protection through weaning. Careful administration of the vaccine (clostridium perfringens type C & D toxoid) along with appropriate handling and storage of the vaccine increases the efficacy of the vaccine products. Conclusion The objective of lamb feeding programs is to provide low cost diets that are balanced and result in rapid and efficient gains and healthy animals. Frequently adjusting the protein concentration in the ration will reduce cost. Many other factors impact the feed cost of gain and lamb health, and all areas must be addressed in today’s market to insure profitable lamb feeding. 7 Table 1. Creep, growing, and finishing rations. Ingredient Corn, lb. Oats, lb. SBM (49%), lb. ISU Lampro 42, lb. Comm. Protein 34, lb. Corn Gluten Feed, lb. Alfalfa Hay EB, lb. Molasses, lb. Limestone, lb. Ammonium chloride, lb. Trace mineral, lb. Selenium (grams) Vit. A, 1,000,000 IU Vit. D, 100,000 IU Vit. E IU Antibiotic or Bovatec, respectively (grams) Calculated Nutrient Content (Dry Matter Basis) Crude Protein, % Total Dig. Nutrients, % Calcium, % Phosphorous, % Creep Feeds 1470 1015 Grower Rations 1240 1500 1375 1435 400 370 425 1170 Finisher 1235 1000 360 270 1750 1675 1535 1170 300 600 450 415 500 160 250 625 325 600 700 300 200 100 100 100 60 60 60 60 60 60 40 40 40 35 35 25 50 25 50 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 .2 .2 .2 .2 .2 .2 .2 .2 .2 yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes 35,000 35,000 35,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 50 or 30 50 or 30 50 or 30 50 or 30 50 or 30 50 or 30 50 or 30 50 or 30 50 or 30 16.7 18.4 21.0 18.1 17.9 18.0 18.0 18.0 18.1 13.4 13.4 13.4 13.3 83.4 81.0 82.7 83.7 80.6 83.4 81.9 79.9 80.8 85.3 83.6 81.5 80.9 .84 .84 .86 1.11 1.14 .74 .74 .75 1.02 .57 .61 .66 .99 .38 .40 .43 .39 .43 .41 .41 .39 .57 .37 .39 .35 .56 8 Table 2. Suggested protein levels for lamb rations as affected by lamb daily gain and weight. Dry matter Daily gain, lb./day Lamb wt., lb. intake, lb./day .5 .6 .7 .8 40 55 70 85 100 > 115 2.4 2.9 3.1 3.4 3.6 3.8 15.9 13.4 12.8 12.0 11.4 10.8 17.0 14.7 13.9 12.7 11.9 11.4 18.6 15.8 14.7 13.4 12.6 11.9 20.4 16.9 15.5 14.3 13.3 12.5 Table 3. Protein supplement (ISU LamPro 42)a formulation fed at Iowa State University McNay Research Farm. Ingredients Amount per ton Soybean meal, 49% Blood meal Limestone Molasses Ammonium sulfate Trace mineral saltb Selenium premixc Zincc Chloratetracycline or Bovatec Vitamin A, IU Vitamin D Vitamin E 1340 lb. 200 lb. 220 lb. 100 lb. 70 lb. 70 lb. 1.3 grams 300 grams 200 grams 7 million 800,000 150,000 Nutrient density, as fed Crude protein NEm (mcal/lb.) NEg (mcal/lb.) Calcium Phosphorous Selenium (ppm) a Supplement is to be fed with whole shelled corn. Should not contain added copper. c Reduce this amount equal to that supplied by trace mineral salt. b The supplement shown above, when fed with corn in the following ratios, provides the nutrient levels listed (dry matter basis) Corna:supplement ratio Crude protein, % Calcium: phosphorous ratio 4 :1 6 :1 8 :1 10 :1 16.2 14.0 12.8 12.0 2.35 :1 1.74 :1 1.38 :1 1.15 :1 a Corn is assumed to have 8.5% crude protein on a dry matter basis. Please be advised that these are very high energy rations. 9 42.4% .69 .46 3.88% .54% 1.27 Table 4. Target slaughter weightsa to produce YG2 carcasses from ewe and wether lambs produced from sire and dam breeds of varying mature weights. Ewe breed mature wt., lb. 250 240 230 Sire breed mature wt., lb. (Wt. of ewes of the breed) 220 210 200 190 180 170 160 150 140 130 120 250 240 230 220 210 200 190 180 170 160 150 140 130 120 163 159 156 153 150 146 143 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 159 156 153 150 146 143 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 156 153 150 146 143 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 153 150 146 143 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 98 94 91 88 85 81 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 98 94 91 88 85 81 78 150 146 143 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 146 143 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 143 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 140 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 98 137 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 98 94 133 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 98 94 91 130 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 98 94 91 88 127 124 120 117 114 111 107 104 101 98 94 91 88 85 a Target slaughter weight =((sire breed mature wt. + ewe breed mature wt.)/2) x .65. Shaded areas indicate desired live weights for market lambs in most commercial markets. Estimates of average mature ewe weights for some U.S. breeds: 230 - Suffolk; 210 - Hampshire; 200 - Columbia; 180 - Dorset, Lincoln, Oxford, Shropshire; 170 - Border Leicester, Corriedale, Dorper, East Friesian, Montadale, Romney, Targhee; 160 - North Country Cheviot, Polypay, Rambouillet, Texel; 150 - Coopworth, Romanov, Southdown, Tunis; 140 - Cheviot, Clun Forest, Finnsheep, Katahdin, Merino, Perendale, St. Croix; 130 - Cheviot, Scottish Blackface; 120 - Barbados, Karakul; 110 - Jacob; 90 - Shetland. 10