November 27-28, 1966: Ferocious Gale and Snowstorm

advertisement

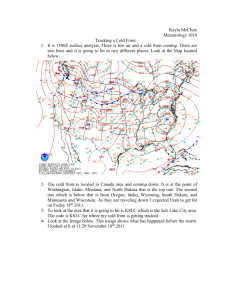

November 27-28, 1966: Ferocious Gale and Snowstorm This storm hit at the peak of Thanksgiving weekend return-trip travel. The week leading up to the storm had been mild and the thawing weather and rain put a damper on the second week of deer hunting season. During Thanksgiving weekend, an upper-air trough began to form and deepen over the central United States. At the surface, low pressure in south-central Canada, which had been pumping mild, southerly winds into the Upper Great Lakes, began to fill, while new low pressure formed in northern Missouri ahead of the deepening trough in the Plains. The Missouri low became the main system and strengthened rapidly, drawing in cold air from the north. Rain quickly changed to freezing precipitation and then snow from northwest to southeast across Upper Michigan. As the storm intensified and lifted northeastward, gale force winds began to buffet the region. Richard Wright, an instructor at Northern Michigan University in Marquette at the time, was visiting family in the Menominee County community of Daggett that Sunday. “It was raining and blowing,” he recalls, “and we were concerned about the weather farther north. We left right after lunch and things were fine until we got to the snow belt around Trenary. It started to deteriorate fast and by the time we got around Skandia, traffic was down to one lane.” He and his wife made it to their home in Harvey. Later that evening they lost power, and with it, their source of heat. They were not alone. Thousands of homes throughout an eight-county region of central and eastern Upper Michigan lost heat and cooking facilities as wind gusts to 60 miles-anhour caused massive power failures. Curtis, in Mackinac County, went without power from 4 p.m. Sunday until well into Monday. The Chippewa County community of Rudyard was blacked out too, as five miles of ice-laden utility poles around the town were brought down by the wind. Farther west, Munising also experienced a blackout that caused the city’s hospital to use emergency backup power. Vicious winds snapped trees and flung them onto power lines around Marquette. The wind was so strong it blew spray from Lake Superior across U.S.-41 near the prison. It was the first time residents had witnessed that spectacle in many years. Half the city was without power at the height of the storm. Baraga and Delta counties also suffered extensive outages. Only a few inches of snow fell in the Copper Country during the storm, while on the east end four to five inches accumulated at the Sault with no real problems. The central and much of the rest of eastern Upper Michigan bore the brunt of the storm. Over a foot of snow accumulated in Marquette. The full gale accompanying the blizzard piled up drifts eight to nine feet deep between Marquette and Negaunee with even deeper drifts around Skandia. Larry Wanic grew up near La Branche in northern Menominee County and enjoyed an extra day of Thanksgiving holiday vacation because of the storm. “I remember the fields,” he recalls. “There was hardly any snow. It didn’t snow more than six or seven inches in this area, but the fields were like you see in North Dakota. They were bare and then you’d have places where the drifts would be five feet.” The blinding, blowing snow brought traffic to a complete standstill during one of the busiest travel days of the year. Hundreds of vehicles became stranded along main thoroughfares throughout the region, from the straits westward to Baraga County. In the Green Garden-Skandia area alone, about 200 vehicles became mired in drifts on U.S.-41 south of Marquette. Most of the stranded travelers camped out on the floor of the Idletime Bar near Yalmer Road and stayed there through much of the next morning. Stalled vehicles still lined the highway on Tuesday morning the 29th, a day after the storm ended. Joe Freeman of Engadine, a small town in western Mackinac County just north of U.S.-2 on M-117, remembers a Greyhound bus stranded in the main intersection of the town at the height of the storm. “Its windshield was busted,” he says. “It was the wind that must have blew an evergreen branch or something…through the window.” The bus was full of students heading back to Northern Michigan University and Michigan Technological University from downstate. The students were herded over to the Town Hall where they were forced to spend the night. “The manager of our store opened up and made sandwiches for the kids,” recalls Freeman. The store manager made lots of sandwiches that evening. After a 75-mile stretch of U.S.2 from the straits to Blaney Park became impassable, 500 students and motorists took shelter in the Engadine Town Hall. Freeman says the students had no goulashes or boots, so some of them put on the town’s firemen’s boots housed at the hall. “The powers-to-be didn’t like that too well,” remembers Freeman with a chuckle. Farther north in the woods of northern Luce County, tragedy struck as the blizzard peaked. The proprietors of Pike Lake Resort had just closed the place down for the winter, as the last of the deer hunters headed south. Faye Leighton had operated the resort since 1941. A widow for over 20 years, she married a longtime family friend, Leslie “Doc” Purman in 1964. As darkness fell that Sunday evening, the couple left isolated Pike Lake and headed toward Newberry on one of the backwoods roads. They became stuck along the way and apparently decided to walk to the Pine Stump Junction Bar for help. The pair struggled through the biting wind and blinding snow for nearly four miles. Exhausted, they probably decided to rest for a while. Their frozen bodies were found cuddled up in a snowdrift beneath a cedar tree on December 1, three days after the storm ended. Ironically, they were less than a half-mile from their destination. A ferocious gale and snowstorm rendered a short hike an insurmountable obstacle that evening in late November 1966.