The national competitiveness/firm competitiveness debate in Britain

advertisement

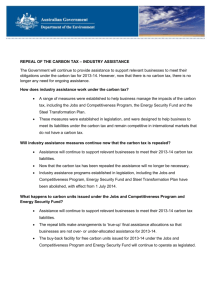

NATIONAL COMPETITIVENESS/FIRM COMPETITIVENESS DEBATE: BRITAIN IN THE 1960s NEIL ROLLINGS University of Glasgow Economic History Society 2008 Nottingham Not be cited without author’s permission Neil Rollings Department of Economic and Social History University of Glasgow Lilybank House Bute Gardens Glasgow G12 8RT N.Rollings@lbss.gla.ac.uk 1 Nearly fifteen years ago Paul Krugman famously counselled that the attention given to national competitiveness was ‘a dangerous obsession’.1 Yet, in many respects, this warning has fallen on deaf ears. More and more league tables of national competitiveness keep appearing, themselves competing to be recognised as the world leader.2 National governments continue to pay close attention to these tables. And, building on Michael Porter’s seminal The competitive advantage of nations, academics continue to address the topic.3 What Krugman failed to appreciate is that, as historians are well aware, such a notion as national competitiveness and government concerns with it, is nothing new – the measures have just become more sophisticated over time. As Jim Tomlinson has set out, in the British case these concerns were closely related to anxiety about relative economic decline and were apparent from the late nineteenth century onwards, although there was a marked change in the 1950s and 1960s as ‘declinism’ became an increasingly dominant paradigm.4 Then national competitiveness was measured in terms of national income, industrial production, productivity and share of world trade, reflecting the emergence of more reliable comparative data in each of these areas. It is the last of these which is of particular relevance to this paper. In the 1960s both Britain and the United States adopted policies to correct their balance of payments deficits. Amongst the measures taken were ones designed to restrict the flow of funds used for overseas direct investment. In the US this took the form of a voluntary control from 1965, which was turned into a mandatory control in 1968 and which lasted until 1974. In Britain the tool used was exchange control, in place since the Second World War, but tightened in 1961 and again in 1965 to ensure that funds were only released for foreign direct investments which would offer a rapid return to the balance of payments. Since exchange control only dealt with transactions outside the Sterling Area, this was supplemented in 1965 by a call for restraint on direct investment in the Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa), which were the main Commonwealth recipients of private direct investment. Although there is a consensus in the historiography that these restrictions had little impact on the levels of foreign direct investment from the US and Britain, these measures were criticised vehemently and consistently by the business communities in both the US and Britain. This paper tries to explain why, and in so doing highlights the emerging tension between competing notions of the value of FDI to a home country and to its competitiveness. This was more explicit in the British case because of related arguments about the low level of domestic investment and the growing influence of ideas about export-led growth suggested in particular by Nicholas Kaldor, a special adviser on economic issues to ministers in the Labour governments between 1964 and 1968. The paper begins with a discussion of the concept of competitiveness, before briefly setting out the controls used to restrict FDI in the US and Britain and their impact. The paper then turns to consider why business complained in such a sustained and vehement way about the restrictions. Paul Krugman, ‘Competitiveness: a dangerous obsession’, Foreign Affairs 73 (1994), 28-44. Building on earlier efforts like the OECD, Industrial competitiveness, there is now the World Economic Forum’s Growth Competitiveness Index and Business Competitiveness Index, the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook, and Robert Huggins Associates, European Competitiveness Index. 3 Michael Porter, The competitive advantage of nations (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2nd ed. 1998). A recent example is Richard HK Vietor, How countries compete: strategy, structure, and government in the global economy (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007). 4 Jim Tomlinson, The politics of decline: understanding post-war Britain (Harlow: Longman, 2000). 1 2 2 Competitiveness There is little debate that the concept of competitiveness is central to the analysis of the individual firm – it is competing against other firms to sell its products and to make profits. It is only when the term is applied to individual countries that the value of the concept becomes disputed. First, although the concept of national competitiveness is bandied about, there is no agreed definition of the term and, as already mentioned, some, like Krugman, find the concept positively unhelpful. Nevertheless, there is agreement that it relates to competitiveness in an international framework and builds on Balassa’s notion of an ability to sell in international markets.5 Thus a commonly quoted definition is that provided by the OECD: ‘the degree to which a country can, under free and fair market conditions, produce goods and services which meet the test of international markets, while simultaneously maintaining and expanding the real incomes of its people over the longer term’.6 From this definition the link to the notion of firm competitiveness is clear but this link is one of Krugman’s main complaints: each nation is not like a big corporation competing in the global marketplace.7 If not analogous to a single firm then others have suggested that national competitiveness represents the aggregation of the ability to sell of each single firm in the country.8 Michael Porter expresses it differently and has criticised the concept of national competitiveness, but unlike Krugman’s rejection of the concept, he suggests that the issue is more about poor phrasing. Rather than addressing national competitiveness, the question needs to be much narrower: ‘Why does a nation state become the home base for successful international competitors in an industry?’9 Given this idea of competing internationally it is unsurprising that trade performance, in particular share of world exports in manufactures and import penetration, have been popular indicators of national competitiveness.10 Even Porter, with his different focus, uses export share statistics extensively in his analysis. However, none of these definitions are explicit in how to deal with multinational enterprise. Similarly, focusing on home country exports fails to capture the contribution of multinational enterprise where some, or even all, production occurs outside the home base of the enterprise. Thus there is a clear distinction between ownership-based and location-based measures of international competitiveness.11 The relationship between the two is unclear. On the one hand the place of production will determine actual trade flows but it is equally clear that the resources and conditions of the home country of a firm influences its competitiveness. Since even today very few firms are truly global, most multinational firms have a clear geographic centre which means that the nature of the relationship matters and Geoffrey Jones and Maurice Kirby, ‘Competitiveness and the state in international perspective’, in G Jones and M Kirby (eds), Competitiveness and the state: government and business in twentieth century Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991), pp. 1-4; and B Balassa, ‘Competitiveness of American manufacturing in world markets’, in B Balassa (ed), Changing patterns in foreign trade and payments (New York: Norton, 1964), pp. 26-33. 6 OECD, Technology and the economy: the key relationships (Paris: OECD, 1992), p. 237. This is also the definition used by the UK government in its competitiveness White Papers in the 1990s. 7 Krugman, ‘Competitiveness’, p. 29. 8 Barbara Dluhosch, Andreas Freytag and Malte Krüger, International competitiveness and the balance of payments: do current account deficits and surpluses matter? (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 1996), p. 4. 9 Michael E Porter, Competitive advantage, p. 1. 10 Jones and Kirby, ‘Competitiveness’, pp. 4-5. 11 Lilach Nachum, Geoffrey Jones and John Dunning, ‘The international competitiveness of the UK: is it eroding or changing form?’, in John Dunning and Jean-Louis Muchielli (eds), Multinational firms: the global-local dilemma (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 35. 5 3 cannot simply be ignored.12 Yet it is equally well recognised that the nature of that relationship is extremely complex and hard to measure with any degree of accuracy or certainty. The extent to which foreign direct investment hinders or helps the performance of the home country is not a new issue. Much has been written on the impact of overseas investment on the British economy in the late nineteenth century, though this was mainly portfolio, rather than direct, investment and where the focus was on the performance of banks.13 While multinationals have a similarly long history their ‘coming of age’ in the 1960s raised very clear issues for national governments.14 On a number of occasions Geoffrey Jones has raised the issue of the relationship between the spread of UK multinationals after the Second World War and Britain’s parallel relative economic decline, particularly Britain’s decreasing share of world exports.15 He contrasts the ability of British companies to hold the second largest stock of FDI in the world after the US and to be the largest direct investors in the US over the postwar period with the decline of domestic manufacturing: British multinational investment must have involved considerable organizational and management skills, or else it could not have been sustained. This suggests that a distinction must be made between the competitiveness of British firms and the competitiveness of the British economy…. The discussion of the “deindustrialisation” of the British economy can mislead if it fails to take account of the continued international competitiveness of Britishowned business enterprise.16 Jones and others’ own brief analysis of this issue found that UK multinationals were more competitive internationally than the UK domestic economy at this time, but that, in contrast to the cases of the US and Sweden, the competitiveness of UK multinationals had fallen at the same time as national competitiveness. In other words, while UK multinationals may have been more competitive than the home economy, no evidence of an inverse correlation, rather the declining competitiveness of both appeared to be complementary.17 Perhaps unsurprisingly, Jones believes that much more research is needed in this area and, more generally, on British multinational enterprise after 1945. 12 Thomas Brewer and Stephen Young, The multinational investment system and multinational enterprises (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 20. 13 For a review see Michael Edelstein, ‘Foreign investment, accumulation and Empire, 1860-1914’, in Roderick Floud and Paul Johnson (eds), The Cambridge economic history of modern Britain vol. II: economic maturity, 1860-1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 190-226. 14 John Cantwell, ‘The changing form of multinational enterprise expansion in the twentieth century’, in Alice Teichova, Maurice Lévy-Leboyer and Helga Nussbaum (eds), Historical studies in international corporate business (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 22. 15 Geoffrey Jones, ‘British multinationals and British business since 1850’, in Maurice Kirby and Mary Rose (eds), Business enterprise in modern Britain: from the eighteenth to the twentieth century (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 196; and Geoffrey Jones, ‘Multinationals’, in Franco Amatori and Geoffrey Jones (eds), Business history around the world (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 359. 16 Geoffrey Jones, ‘Great Britain: big business, management, and competitiveness in twentieth-century Britain’, in Alfred Chandler, Franco Amatori and Takashi Hikino (eds), Big business and the wealth of nations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 136. 17 Nachum et al, ‘International competitiveness’. 4 US and UK controls over foreign direct investment The 1960s and 1970s saw an explosion of interest in multinationals. Leading this debate was Raymond Vernon’s Sovereignty at bay but this was just one of many works in the emergence of the study of multinational enterprise into a cynosure.18 As the US Tariff Commission put it: it was ‘beyond dispute that the spread of multinational business ranks with the development of the steam engine, electric power, and the automobile as one of the major events of modern economic history’.19 This might sound like hyperbole but well characterised feelings at the time. In the 1970s concerns about the impact of multinationals on home economies came to centre around the issue of job losses but prior to this the key issue revolved around the impact on the balance of payments, more specifically, whether foreign direct investment paid for itself in terms of inflows of funds coming back to the home country and exports which would not otherwise have occurred, and if so, how quickly this repayment happened. This was a very live issue given the huge and rapidly growing outflow of funds from the US and, to a lesser extent, from the UK and the anxieties about balance of payments deficits in both countries, as shown in table 1. In the US the government responded to the growing balance of payments deficit by introducing the Interest Equalisation Tax in 1963, with the aim of reducing the perceived favourable tax treatment of overseas investment. Attention turned to FDI more directly in 1965 with the introduction of the Voluntary Credit Restriction Program. As part of this program US firms were asked to cooperate in limiting the outflow of capital to their affiliates in industrial countries (with the exception of Canada) and to increase dividend inflows.20 In 1968 the program became mandatory and direct investors (those owning 10 per cent of the equity of a foreign affiliate (as against 25 per cent in the UK)) were allowed to choose among a range of ways of calculating their investment quotas and had to file annual (sometimes quarterly) returns such that direct investment would be reduced by $1 billion below the 1967 level. Countries in receipt of US direct investment were divided into three groups: schedule A – the less developed countries; Schedule B – those developed countries judged to be dependent on continuing inflows of US capital (including Britain); and Schedule C – all other countries (including Western Europe). The implications were that control was least severe on schedule A countries and most severe on investment in schedule C countries. With the change in administration the controls were gradually eased from 1969 and finally removed in 1974. UK controls were rather different and more longstanding. Controls on the export of capital went back to the First World War but post-Second World War controls centred on exchange control, which had been introduced under emergency 18 Raymond Vernon, Sovereignty at bay: the multinational spread of U.S. enterprises (New York: Basic Books, 1971). For a recent account of the rise of multinationals in this period see Geoffrey Jones, ‘Multinationals from the 1930s to the 1980s’, in Alfred Chandler and Bruce Mazlish (eds), Leviathans: multinational corporations and the new global history (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 81-103. 19 Quoted in Neil Hood and Stephen Young, The economics of multinational enterprise (London: Longman, 1979), p. 1. 20 For summaries of the US controls see Hood and Young, Economics, pp. 300-2; and AE Safarian, Multinational enterprise and public policy: a study of the industrial countries (Aldershot: Edward Elgar, 1993), pp. 366-70. For more detailed accounts see John Ellicott, ‘United States controls on foreign direct investment: the 1969 program’, Law and Contemporary Problems 34(1) (1969), pp. 4763; H David Willey, ‘Direct investment controls and the balance of payments’, in Charles Kindleberger (ed.), The international corporation: a symposium (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970), pp. 95-119; and Alec Cairncross, Control of long-term international capital movements: a staff paper (Washington: Brookings Institution, 1973), pp. 39-50. 5 powers at the outset of the war and then was made permanent by the Exchange Control Act 1947.21 Over the 1950s the restrictions imposed under the legislation were gradually eased but they were tightened from 1961 onwards. Until then foreign exchange was provided at the official exchange rate for all overseas investments (portfolio or direct) as long as they complied with the restrictions then in place. Direct investment within the sterling area was allowed freely - investment in the Commonwealth was ‘a vital economic and political interest of the UK’ and no additional controls were deemed desirable.22 In contrast, private direct investment in the non-sterling area had to show a positive gain to the economy, in particular to the balance of payments, but liberalization meant that control was not rigorous. By the late 1950s the Bank of England was delegated to deal with any applications by firms wanting to invest less than £100,000. All other cases went to a governmental committee for decision. By the late 1950s it was clear that few applications over £100,000 were being refused (5 out of 79 applications in 1958-59) and so at the end of 1959 the Bank was allowed to decide on applications up to £500,000 (64 of the 79 applications).23 Then in the summer of 1961 a series of emergency measures were introduced to alleviate Britain’s balance of payments problems. As a result, the exchange control policy adopted set out two criteria for judging applications for direct investment in the non-sterling area: ‘clear and commensurate benefits in UK export earnings’ within 18 months, or the development of a demand for British exports unrelated to the original investment.24 In addition, the earnings of overseas subsidiaries had to be remitted back to the UK parent as far as possible. In practice the eighteen-month period was operated flexibly, soon raised to two years, and within a year the policy was being applied more liberally.25 From May 1962 those companies refused foreign exchange at the official rate were often allowed to buy investment currency on the dollar switch market, although this involved the payment of a premium, the size of which varied over time (as shown below). Also, any ‘reasonable’ application for less than £25,000 of foreign exchange was also always approved. Further relaxations followed on the proceeds of the sale or liquidation of post-1939 direct investments in the non-Sterling Area. However, by 1964 the Treasury was already examining ways of imposing further exchange control restrictions, including consideration of imposing exchange control within the sterling area.26 Restrictions on overseas investment were tightened in the 1965 budget so that only direct investment which constituted no burden on the balance of payments was allowed.27 In addition, a ‘Voluntary Programme’ was introduced to control direct investment in some developed sterling area countries, namely Australia, South Africa, New Zealand and Eire. At first, this was applied to 300 individual firms but in 1966 this was broadened to all firms. A further restriction was ‘the 25 per cent rule’, whereby the proceeds of a sale by a UK resident of foreign ‘The UK exchange control: a short history’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 7 (1967), pp. ?? TNA T318/916, ‘Overseas investment policy’, undated, para 38, attached to ‘Review of external investment’, DHF Ricketts to L Rowan, 5 July 1956. 23 TNA T318/918, GH Tansley (Bank of England) to FW Glaves-Smith (Treasury), 12 November 1959. The application and refusal figures relate to ‘the last year’ which might be 1958-59 or 1958. 24 MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/4, E.252.C.61, ‘The present attitude of the Treasury towards new investment in the non-Sterling Area’. 25 MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/4, Meetings of the FBI Overseas Investment Committee, 14 December 1961 (E.263.61) and 4 June 1962 (E.96.62), and MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/9, ‘Note of a meeting at the Treasury on Wednesday October 30th 1963’, November 1963. 26 See TNA T326/289 for the discussion of these proposals. 27 TNA T295/524, OIG (66)2, ‘”Guidelines” for overseas investment’, 9 February 1966. 21 22 6 assets (direct or portfolio), had to be exchanged for sterling at the official rate, not only discouraging such sales but also reducing the amount of currency coming on to the market. These policies remained in place for the rest of the decade.28 Impact of the US and UK controls There is general agreement that both the US and UK controls impacted upon FDI. However, this was less in terms of the actual level of FDI undertaken by firms outside the US and UK than in respect of the form of funding. Looking at US controls first, there was a belief at the time that the mandatory control, in particular, had a significant downward impact on capital transfers from the US and thus from a narrow perspective was successful in alleviating the size of the balance of payments deficit.29 Table 1 shows how US direct investment funded by capital transfers from the US fell in the second half of the sixties. There was a gradual decrease in the period of voluntary restraint and a sharp reduction in 1968, well beyond the $1 bn. target. Table 1 Direct investment transactions, excluding Canada, 1965-69 ($ bn) Selected Transactions Data for 3300 Office of Foreign Direct Investment reporting firms Projections From 469 major companies 1969 Total of all schedules, excluding Canada Reinvested earnings Capital transfers, including use of foreign borrowing Direct investment, including use of foreign borrowing Use by direct investor of longterm foreign borrowings Direct investment, excluding use of foreign borrowings 1965 1966 1967 1968 1.02 3.10 1.08 3.44 0.92 3.35 1.21 2.47 1.67 3.42 4.12 4.52 4.27 3.68 5.09 (0.11) (0.65) (0.56) (2.22) (2.30) 4.01 3.87 3.71 1.46 2.79 Source: Willey, ‘Direct investment controls’, p. 99. What the table also shows is how, despite the reduction in transfers, the decline in the level of direct investment was nothing like as substantial because of the increased use of foreign borrowing. Indeed, Don Cadle, the acting director of the OFDI was confident enough to assert in 1969 that ‘after talking to many hundreds of business, we have no reason to believe that the US companies, using either foreign capital or US capital under their quotas, did not invest pretty much what they wanted to invest last year’.30 This was contested by some economists at the time, for example Peter Lindert, but the contemporary official view seems to have become the conventional wisdom.31 Much the same story has been told for the UK and the impact of exchange control. The Treasury certainly believed that exchange control was reducing the outflow of capital used for foreign direct investment.32 Equally, Cairncross thought that the investment currency premium was deterring FDI outflows in the period 1963Central Office of Information, Britain’s international investment position (London: HMSO, 1971), pp. 16-36. 29 Cairncross, Control, pp. 50-1; and Willey, ‘Direct investment controls’, pp. 99-102. 30 Don Cadle, quoted in Cairncross, Control, pp. 44-5. 31 Peter Lindert, ‘The payments impact of foreign investment controls’, Journal of Finance 26 (1971), pp. 1083-99. For a more recent restatement of the Cadle view see Thomas Brewer and Stephen Young, The multinational investment system and multinational enterprises (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 102. 32 MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/10, E.219.64, ‘Note of a meeting at the Treasury’, 26 June 1964. 28 7 65 having risen from about 3 per cent in 1962 to around 10 per cent.33 Since the premium continued to increase (38 per cent in 1969 and peaking at 63 per cent in 1975) it would be expected ceteris paribus that this was a significant disincentive in funding FDI by this means.34 Yet the impact on UK FDI was more limited. The trend in UK FDI in the non-sterling area remained clearly upward and Cairncross saw no marked divergence between sterling and non-sterling investment.35 His first impression from the figures was ‘one of astonishment at the very large increase, particularly in the non-sterling area, over a period when the controls were being steadily tightened. Direct investment cannot have been greatly restricted over the period as a whole.’36 As shown in Table 2, in 1963 less than five per cent of applications were refused, amounting to only 1.6 per cent of the applications’ total value and Table 3 again shows a relatively small level of refusals, both suggesting that exchange control was not much of a deterrent to overseas investment. Even when the criteria were at their severest most firms envisaging applying under exchange control were able to meet the criteria of a rapid return in terms of export growth.37 Table 2 Exchange control in 1963 Number of applications Total sum involved (£m.) Full approval at the official rate 959 85 of exchange Full approval for financing via 9 30 borrowing abroad Given access to the ‘switch’ 484 99 dollar market Refused 75 3.5 TOTAL 1527 217.5 Source: MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/10, ‘Note of a meeting held at the Treasury on Friday, June 26th, 1964’. Table 3 Exchange control authorisations and refusals 1964-66 (£ m.) 1964 1965 Official exchange Remittances 42.2 29.4 Guarantees 6.0 21.3 Exports f.o.p. 8.0 3.4 Investment currency Remittances 78.0 80.3 Guarantees 74.7 149.6 Short-term borrowing 1.2 3.3 Euro-dollar borrowing 5.5 4.0 Long-term borrowing* 19.6 14.5 235.2 305.8 Total Authorisations 3.2 17.0 Refusals * Borrowing without guarantees by UK parent companies 1966 6.0 46.4 98.8 2.5 12.0 31.7 197.4 1.0 Source: TNA T295/168, AK Rawlinson (Treasury) to JR Bracewell-Milnes (CBI), 22 June 1967. 33 Cairncross, Control, pp. 64-5. Hood and Young, Economics, p. 306. See also PK Wooley, ‘Britain’s investment currency premium’, Lloyds Bank Review 113 (July 1974), pp. 33-46. 35 Cairncross, Control, p. 66-7. 36 Cairncross, Control, p. 68. 37 TNA T295/163, ‘Overseas investment and exports’, by AK Rawlinson, 8 June 1965. 34 8 As in the US case, the controls encouraged a change in methods of financing FDI with increased reliance on unremitted profits, direct borrowing abroad by parent companies and Eurocurrency borrowing. There were few cases found of companies being unable to finance FDI even by bodies looking for such evidence.38 Again, like the US case, this interpretation of the impact of exchange control – reducing capital transfers but not FDI because of the use of alternative sources of funding – has become the conventional wisdom.39 Complaints from the business communities If these accounts of the impact of controls are right then one question remains unresolved. If these controls had little impact on FDI levels why did the business communities in both the US and the UK complain so vehemently and so often about them? In many respects, the reasons, I suggest, were common but perhaps more explicit in the UK case.40 Certainly business on both sides of the Atlantic was outspoken in its opposition to the maintenance of these controls.41 A crucial area of disagreement surrounded the issue of the contribution of FDI to the balance of payments. It was common, including in government, to view exports and FDI as substitutes, though some saw them as complementary. Academics were sharply divided on the issue, as well as on the period required for direct investment to induce a positive contribution to the balance of payments. Two famous studies embarked on addressing these crucial and contentious issues in the mid-1960s, one in the US and the other in the UK. In the US Hufbauer and Adler produced Overseas manufacturing investment and the balance of payments while Brian Reddaway led a team at Cambridge which produced an interim and final report on the Effects of UK direct investment overseas.42 Hufbauer and Adler considered a wider set of hypotheses but when they used the same methodology as Reddaway they found a smaller immediate balance of payments adverse impact, a quicker return and higher long-term benefits to the balance of payments.43 However, neither study resolved the underlying issue mainly because it was incapable of being resolved. Reddaway showed that while the average value of the FDI which took the form of exports of plant and machinery was 11 per cent over the period 1955-64, this varied between sectors markedly: only 1 per 38 Industrial Policy Group, The case for overseas direct investment (London, 1970). Hood and Young, Economics, p. 310; D Bailey, G Harte and R Sugden, Transnationals and governments: recent policies in Japan, France, Germany, the United States and Britain (London: Routledge, 1994), pp. 150-6. 40 Or this may be a consequence of differential knowledge. 41 On the US see Jack Behrman, National interests and the multinational enterprise: tensions among the North Atlantic countries (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970), pp. 91-2; Cairncross, Control, p. 44; Safarian, Multinational enterprise, p. 369; and Raymond Vernon, US controls on foreign direct investments – a reevaluation (New York: Financial Executives Research Foundation, 1969). On the UK see Industrial Policy Group, Case. 42 GC Hufbauer and FM Adler, Overseas manufacturing investment and the balance of payments (Washington, DC: US Treasury Department, 1968); WB Reddaway, Effects of UK direct investment overseas: an interim report (London: Cambridge University Press, 1967) and idem, Effects of UK direct investment overseas: final report (London: Cambridge University Press, 1968). 43 Hood and Young, Economics, p. 313. For a comparison of the two studies see John Dunning, Studies in international investment (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1970), pp. 107-17; and Hufbauer and Adler, Overseas, pp. 90-2. 39 9 cent for the paper industry to 21 per cent for motor vehicles.44 Also both studies showed that a key assumption was what would happen in the absence of the FDI: would the investment still be undertaken by some other party or would it be possible to maintain exports? There was no general answer to this question; it was dependent on the circumstances in each individual case given the complex and heterogeneous factors involved in each investment decision. In this respect there has been little advance on Bergsten et al.’s depiction of the relationship between foreign investment and exports as ‘haphazard’.45 That the issue was so opaque and academia was unable to provide a definitive or consensual resolution in part explains why there was business criticism of the restrictions in the US and UK. But this is an insufficient explanation by itself: both business communities were adamant that FDI contributed to the balance of payments positively, quickly and significantly. US officials expected that the 1968 firming up of restrictions would stir up the business community as business believed this would be ‘killing the goose that lays golden eggs’.46 The business community in Britain agreed if in less colourful terms. As the President of the Federation of British Industries told Jim Callaghan, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1965: If overseas investment on its recent scale could be shown to be a net burden on the balance of payments, we should support its reduction until the economy was strong enough to sustain it. If the problem were that of balancing shortterm loss against long-term gain, we would understand that in a precarious situation policy might have to be determined by short-term needs however great the long-term sacrifice might be. What we find difficult to understand is the decision to reduce overseas investment both in the long and in the shortterm on the footing that it is imperative for the short-term needs of the balance of payments - and this in the face of evidence that it may even aggravate our short-term imbalance.47 The letter went on to call for the government to authorise an independent study of the subject, something which the FBI had been considering since 1961.48 That the government did not respond marks one clear distinction between the American and British cases. Hufbauer and Adler’s study was sponsored and financed by the US Treasury Department. In contrast, Reddaway’s study was funded by the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), the FBI’s successor from 1965. The government assisted the study but refused to sponsor it. A second difference was that the US Department of Commerce clearly defended the interests of business FDI in discussions within the US administration.49 In contrast, its UK equivalent, the Board Reddaway, Final report, p. 374. For more on this aspect see David Robertson, ‘The multinational enterprise: trade flows and trade policy’, in John Dunning (ed), The multinational enterprise (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1971), pp. 191-2. 45 Fred Bergsten, Thomas Horst and Theodore Moran, American multinationals and American interests (Washington: Brookings Institution, 1978), p. 97. 46 FRUS 1964-68, Volume VIII, International monetary and trade policy, memorandum 137, Secretary of the Treasury Fowler to President Johnson, 8 August 1967. The same metaphor is referred to in dismissive terms by Willey, ‘Direct investment controls’, p. 118. 47 TNA T295/163, H.53.65, the FBI President to James Callaghan, 21 May 1965. 48 MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/4, meeting of the FBI’s Overseas Investment Committee, 14 December 1961. 49 FRUS 1964-68, Volume VIII, memorandum 106, Secretary of State for Commerce (Connor), minutes of the meeting of the Cabinet Committee on the Balance of Payments, 5 December 1966. 44 10 of Trade, stressed the importance of exports over FDI. By the late 1960s even the Foreign Office believed that the Board of Trade’s ‘excessive preoccupation with visible exports is antediluvian’.50 UK export fetish and competitiveness One reason for the Board of Trade’s preoccupation with visible exports was its belief that Britain’s share of world trade was an important indicator of competitive performance.51 Correcting the balance of payments deficit was a key goal of exchange control but there were other motives as well related to notions of national competitiveness and relative economic decline. In particular, it became increasingly common to associate Britain’s low growth rate with a low level of domestic investment, an argument made by Andrew Shonfield amongst others.52 While the Board of Trade focused on the maximisation of exports, the Treasury emphasised the differences between domestic investment and foreign investment. Keynes, amongst other economists, had criticised a preference for foreign investment (in this case portfolio investment) over domestic investment in the 1920s.53 He distinguished between the social return to investment and the private return, arguing that the social return was higher for domestic investment than for foreign investment because at a minimum the assets would be retained in the home economy.54 This was a view commonly held in Whitehall in the 1960s.55 One report written prior to the Reddaway reports summed up official thinking: Widely different views are held about the effect of overseas investment on the domestic economy. But it would probably be generally acknowledged that, although the commercial yield on investment at home and abroad may not differ much, the total social return (including the effects on productivity and so on) are likely to be greater in the case of domestic investment. This is not to say, however, that a reduction in investment abroad would necessarily lead to a corresponding increase in investment at home.56 Exchange control could help to change the balance between foreign and domestic investment but was seen as a temporary crisis measure (although it had been in place for many years). This was one reason for the introduction of corporation tax in 1965. It was strongly believed in Whitehall that there was a fiscal incentive in favour of foreign investment over domestic investment which corporation tax was meant to remove: ‘the corporation tax is the corner-stone of the government’s long-term TNA FCO70/1, ‘British industrial investment in Europe’, by KD Jamieson (Export Promotion Department, FCO), 30 June 1969. 51 Tomlinson, Politics of decline, p. 20. 52 Andrew Shonfield, British economic policy since the war (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1958). See also Jim Tomlinson, The Labour governments 1964-70 volume 3: economic policy (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), pp. 32-4 and 95-6. 53 See Hood and Young, Economics, pp. 284-8. 54 JM Keynes, ‘Foreign investment and national advantage’, The Nation and Atheneum (1924), pp. 584-7. 55 For example TNA T318/229, ‘Reddaway’, Walker to Rawlinson, 7 March 1967. See also Sir Robert Shone, Investment and economic growth (Stamp Memorial Lecture 1966) (London: Athlone Press, 1966), p. 18. 56 TNA T326/289, OI(WP)(64)24(Final), ‘Report of a working party on overseas investment’, June 1964, p. 31. 50 11 strategy to produce a shift of emphasis away from investment abroad towards that at home’.57 While this was a widely held view in the Treasury probably its strongest exponent was Nicholas Kaldor, one of the special economic adviser appointed by the Labour government.58 Kaldor argued for ever tighter controls on foreign investment but others in the Treasury believed he had over-egged his case: ‘Why does any government permit overseas investment if it is so contrary to the national interest?’59 Kaldor’s thinking was informed by the ideas he was developing and famously presented in his inaugural lecture in Cambridge, Causes of the slow rate of economic growth of the UK.60 Here he emphasised the importance of increasing returns to manufacturing activities, which were not available to services or primary production, and that, as a result, the growth of manufacturing production was likely to exert a dominating influence on the overall growth rate. He argued that in an open economy, like Britain’s, it was the trend growth rate of exports which governed the growth rate of production. With increasing returns, any initial advantage in export competitiveness would also tend to be cumulative. This idea of export-led growth, to become so influential in development economics, also offered a solution to Britain’s economic problems, Kaldor argued.61 It was this concern with the importance of manufacturing that lay behind the emphasis on the dangers of deindustrialisation in the Cambridge school of economics. But this also underpinned Kaldor’s policy advice when in Whitehall with its emphasis on the importance of domestic investment over foreign investment and what amounted to an export fetish.62 The UK business community’s response Kaldor implicitly raised a problem with his approach and which helps to explain the alternative position taken by business, which argued throughout the 1960s that the return on FDI was far higher than the government believed and even than Reddaway suggested. Kaldor emphasised the importance of economies of scale in industry as the main engine of fast growth and went on to suggest that their benefits could continue to be reaped ‘by increasing the degree of interdependence of British industry with the industries of other countries’.63 What Kaldor had in mind was some notion of national champions, which the Labour government tried to encourage with the establishment of the Industrial Reorganisation Corporation. What he failed to appreciate was that business could achieve international interdependence by means other than just by exporting by national champions; that is he failed to understand the diverse reasons why firms might indulge in foreign direct investment. This was not simply about the relative yield on capital but related to the dynamics of the growth of the individual firm in which FDI was only one aspect of the subject.64 As Charles Kindleberger TNA T295/167, ‘Chancellor’s meeting with the President of the CBI’, unsigned, 4 July 1967. Anthony Thirlwall, Nicholas Kaldor (Brighton: Wheatsheaf, 1987), pp. 228-57. 59 TNA T 295/163, DF Hubback to Rawlinson, ‘Return on overseas investment’, 21 November 1966. Other correspondence in this file makes similar points on Kaldor’s arguments. 60 Nicholas Kaldor, Causes of the slow rate of economic growth of the UK Causes of the slow rate of economic growth of the UK (London: Cambridge University Press, 1966). 61 Nicholas Kaldor, ‘Conflicts in national economic objectives’, in Nicholas Kaldor (ed), Conflicts in policy objectives (Oxford: Blackwell, 1971), p. 15. 62 On this approach see for example Michael Kitson and Jonathan Michie, The political economy of competitiveness: essays on employment, policy and corporate performance (London: Routledge, 2000). 63 Kaldor, Causes, p. 32. 64 Cairncross, Control, p. 24; David Shepherd, Aubrey Silbertson and Roger Strange, British manufacturing investment overseas (London: Methuen, 1985). 57 58 12 recognised, ‘The choice among exporting, licensing technology, forming cartels, entering contracts, joint ventures, and forming a wholly-owned foreign subsidiary is often a very close one’.65 This indeed was the argument put forward by the UK business community and which most helps to explain the vehemence of the business complaints about restrictions on FDI. British business had always seen a closer complementary link between investment and exports than the Treasury. But over the course of the 1960s the FBI increasingly emphasised the internationalisation of business as part of its critique of exchange control and corporation tax. As early as 1964 an internal report on interviews with sixteen major UK exporters noted: They [companies] regard direct exports and other ways of earning money overseas in the same light. Their approach is to look at all areas of the world and examine the methods by which they can get the best return - whether by export, licensing and know-how agreements, local assembly or manufacture, or any combination of these. In this there is a dichotomy of thinking between industry and government which is in part a result of the divergence of interests between company and country in the short and medium term and in part, as it seems to industry, of a lack of understanding by government of the realities of overseas business.66 By 1969 the CBI’s paper to the National Economic Development Council on direct investment overseas made much the same point but by relating this to the changes that had occurred: It should be pointed out how important international capital flows, and particularly flows of direct investment, have become in the international economy since the war and especially in the last ten years. It is estimated that the volume of production of overseas manufacturing subsidiaries of international companies now exceeds the volume of free world trade in manufactures. The movement of capital has become has become as important as the movement of goods as an instrument for realising the gains - in terms of increased output and income - to be had from international specialisation. The initial impetus to internationalisation of production after the war came from the dismantling of pre-war cartels and world market sharing agreements, and from the tendency of countries to promote domestic industrialisation behind protective barriers. Subsequently, the process has gained impetus from increasingly severe international competition, where even marginal benefits from the location of investment may be crucial, and from the desire to exploit the fruits of technological innovation over the widest possible market.... As Britain’s external difficulties have increased, the outflow of investment has come under scrutiny and criticism, and it has been suggested that overseas investment is a luxury that we cannot afford. Critics sometimes imply that British companies should have sought to build up their overseas Charles Kindleberger, ‘Summary: reflections on the papers and the debate on multinational enterprise: international finance, markets and governments in the twentieth century’, in Teichova et al. (eds), Historical studies, p. 229. 66 MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/10, E.382.64. 65 13 sales by means of direct exporting alone, and that investing overseas is an alternative, or addition to, exporting. Such a view is based on a complete misunderstanding of the nature of international competition. Investments abroad are undertaken by manufacturing companies for many diverse reasons. Essentially, however, industry invests overseas because, in a particular commercial situation, foreign investment is the only appropriate competitive weapon.... All [reasons for overseas investment] are related to the requirements of establishing and maintaining an effective competitive position in world markets when failure to invest will strengthen foreign competitors. Hence, the consequences for the competitive stance of a particular company, and ultimately of the whole British economy, if overseas investment is discouraged can be extremely serious.67 A group of senior industrialists wrote similarly: It is not too much to say that through overseas investment a new world economy is taking shape…. It is evident that we are passing through a new and remarkable process of international economic integration. Any country which stands aside from, or seriously blocks, these global movements is only too likely to wound itself, or damage other countries, or do both.68 By the end of the decade this was becoming recognised in some parts of Whitehall. Thus to give the full quote of the criticism of the Board of Trade by the Foreign Office: ‘This attitude and the excessive preoccupation with visible exports is antediluvian in these days of international marketing and international firms’.69 Conclusion It is only in this light that sense can be made of not only why the British business community was so vociferous in its condemnation of any restrictions on FDI in general but also the complaints about specific consequences of the policies. It was accepted that existing multinationals and other large companies were able to maintain FDI by accessing foreign borrowing or by reinvesting overseas profits. However, this was not possible, it was argued, for smaller firms embarking on FDI for the first time. The bureaucracy, cost and uncertainty associated with exchange control and the investment currency premium which might have to be paid could act as a serious disincentive. The FBI’s Overseas Investment Committee did not normally consider individual cases but one that it did was the case of Beckett, Laycock & Watkinson Ltd. which related to this very issue.70 The company planned to take a controlling interest in an Italian company as a means of gaining access to that market. The company was turned down for official exchange but given permission for the investment to take place via the switch dollar market. However, the company was TNA T295/639, Davies, ‘Overseas investment: two CBI occasional papers’, September 1969, pp. 1516. 68 Industrial Policy Group, Case, p. 3. 69 TNA FCO70/1, ‘British industrial investment in Europe’, by KD Jamieson (Export Promotion Department, FCO), 30 June 1969. 70 MRC MSS200/F/3/E3/32/6, unsigned to K. Johnson (FBI), 2 November 1962, and Johnson to Sir Henry Wilson-Smith (chair FBI Overseas Investment Committee), 5 November 1962. 67 14 unhappy at the premium it would have to pay to obtain the necessary currency to make the investment. Even if exchange control did not act as barrier to smaller firms raising funds for FDI, there was still a concern that it involved more work, which could be a disincentive just when business believed it had to be ratcheting up its international undertakings to retain its competitiveness.71 Moreover, it was argued, that while small foreign investments had the highest proportion of failures, this group also had the largest number of investments offering a return of over 20 per cent.72 Secondly, there was no consideration of the impact of exchange control on the strategy adopted by firms when embarking on FDI. Given the pressure to show a quick return to the balance of payments it would be expected that companies adjusted their strategies accordingly. Certainly, British business favoured acquisition as a method of FDI in order to build up a presence in a market quickly. No research has to date been done on why this was the case but one study has suggested that there was a link between this strategy and the higher number of failures experienced by British firms compared to companies from other countries investing in Western Europe.73 If the sources are available this is an area for further research. In the 1960s it was understandable that national governments and macroeconomic economists found it hard to think at the micro-level of the individual firm and to recognise the internationalisation of production as a trend that could not be stopped. Yet it illustrates a fundamental difference of perspective about ideas of competitiveness that existed at that time and where notions of national competitiveness and firm competitiveness were not only different but in conflict. Both sides in the debate, business and the economic departments of government, were adamant that their view was the correct one, but, as was illustrated by Hufbauer and Adler in the US and Reddaway in the UK, the situation was less clear-cut in practice. Thus these positions were ones of faith and belief rather than based on clear evidence. Equally, both reflected concerns with Britain’s perceived economic decline and how to respond to it but that response was markedly different. In trying to restrict the development of multinationals it is unclear what long-term impact this had on the performance and strategies of these firms. Nevertheless, this debate has been ongoing ever since. 71 Industrial Policy Group, Case, p. 36. Industrial Policy Group, Case, p. 33. 73 John Kitching, Acquisitions in Europe: causes of corporate successes and failures (Geneva: Business International, 1973). 72 15