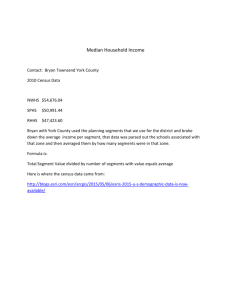

Market Segmentation

advertisement