Female Fighter Pilot, 93, Takes Ride of a Lifetime

advertisement

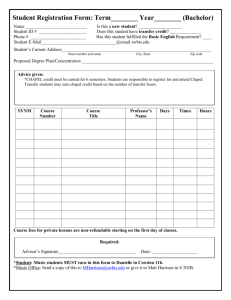

Female Fighter Pilot, 93, Takes Ride of a Lifetime HUNTINGTON BEACH, Calif. (March 10) -- It's been 66 years since Violet Cowden flew fighter airplanes during World War II, but when she took to the skies recently off the coast of Southern California, it was like she was home. "It's like I never left," said Cowden, 93, who flew a light fighter plane for an hour, completing stunts that included barrel rolls and a mock dogfight with two other airplanes. "I feel more comfortable in the air than I do in a car," she told AOL News. Cowden took the flight Feb. 26 as a prelude to an even more exciting event -- receiving a Congressional Gold Medal. As part of the dwindling group of Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs, Cowden and her sisters in flight received the highest honor bestowed upon a civilian during a ceremony today at the U.S. Capitol. Although the WASPs worked for the military, they were not enlisted and their place in history has been largely ignored until now. "I wish more of us could be here," Cowden said from her Huntington Beach home. "Every year we lose more and more." Air Combat USA Violet Cowden poses in Fullerton, Calif., with backup pilot Mike "Maverick" Blackstone on Feb. 26. She and fellow WWII female pilots are to be awarded a Congressional Gold Medal on Wednesday. Of the 1,102 certified WASPs, only about 300 are still alive. Of those, about 200 attended the Capitol ceremony. Relatives of the deceased pilots received medals in their honor. "The medal is something that we did not expect, so of course we are very pleased," said Pearl Judd, 87, a WASP from southern California. "When we were discharged in December 1944, we were told to go home and our records were sealed. We didn't get our veteran's status until 1977 and didn't have the right to have a flag on our coffin until after 2000." Judd told AOL News that she fell in love with airplanes as a child and signed up to join the WASPs when she heard of its formation. WASPs were used to test and ferry war planes across the United States, freeing their male counterparts for deployment in battle. The pay was $150 a month during training, with a $100 raise after graduation. Recruits had to pay for their own room and board and uniforms. Judd was a test pilot, making sure airplanes that needed repair were worthy to go back into battle. "They tried out everything on us -- we flew every plane that they had on the Air Force menu from [the] first jet to the B-29," Judd said. "The B-29 was a little touchy. Its engines caught on fire." Cowden had the most glamorous job of the group -- she flew the fabled P-51 Mustang fighter plane from factories to various military bases around the country. The P-51 has been credited with winning the war by guarding the larger bomb-dropping aircraft from attack. Its lightness and speed made it a match for any approaching enemy aircraft. "I've never felt afraid of flying," said Cowden, who sometimes flew the single-seat aircraft for five hours at a stretch. "I'm so comfortable in the air." The former first-grade teacher from South Dakota grew up on a farm and wanted to fly long before she knew planes existed. As a young woman, she scrimped to take flying lessons and, when the war broke out, she tried to enlist. "I thought I would be flying up and down the coast looking for the Japanese," she said. "I didn't think I'd be in combat, but I would've loved it." Asked if she had wanted to be deployed over Berlin, Cowden piped: "Absolutely. No question." Air Combat USA Then and now: Cowden posed, left, on a fighter plane during her time as a WASP in World War II and recreates the moment in Fullerton, Calif., on Feb. 26. "It's like I never left," she said. Combat or not, the petite pilot endured some prejudice in her job from men who thought she was overstepping her bounds. "Once I delivered an AT-6 [aircraft] in Kansas. It was supposed to be the commander's personal plane. He refused to accept the plane when he saw that I had delivered it," Cowden said with a smile. "When I got out of the airplane, wherever I went, it was a shock usually." Cowden said the GIs would often watch her landings and then tease her if the plane bounced -- which was infrequent. One of her most notable achievements was delivering the first P-51 to the Tuskegee Airmen, the famous group of black fighter pilots. After the war ended, Cowden packed up her navy blue polyester uniform and headed to California, where she opened a ceramics business. She married and had a child, but her days as a pilot were just a prelude to even more adventures. "My daughter and I backpacked for three months around much of the world," she said. The 1966 trip included the Great Wall of China, Taiwan, India, Germany, England and Sri Lanka. Cowden also likes to hang glide and skydive. At 93 years young, knitting and jigsaw puzzles aren't her deal, and she doesn't go to the local senior center. "I don't fit in," she said. Cowden attributes her youthfulness and vigor to her frame of mind. "No matter how bad things were, I thought there must be something good happening, so I always tried to look at the best side of life rather than the negative," she said. Mike "Maverick" Blackstone was in the cockpit as a backup pilot during Cowden's recent flight. He flew the plane during takeoff, but the rest of the flight and the landing were under Cowden's control. "She is a great pilot," said Blackstone, a retired airline pilot who works for Air Combat USA, which stages mock dogfights and invited Cowden to participate. "You would assume someone her age would jut sit there and rely on co-pilot," Blackstone told AOL News. "It was just like back in the '40s. She had a grin on her face and knew where she was going."