Management Research and Practice - E

advertisement

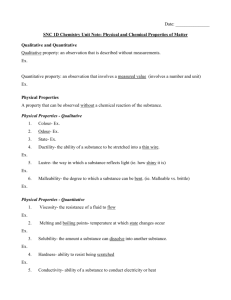

European Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 1450-2267 Vol.28 No.1 (2012), pp. 128-137 © EuroJournals Publishing, Inc. 2012 http://www.europeanjournalofsocialsciences.com Linking Philosophy, Methodology, and Methods: Toward Mixed Model Design in the Hospitality Industry Mousa A. Masadeh Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, College of Archaeology Tourism & Hotel Management, Petra, Jordan E-mail: jordantourism@hotmail.com Tel: +962 7775620356 Abstract This paper discusses some of the unique philosophical and methodological problems facing research in the hospitality industry, and argues that a mixed methodological approach, based on a foundation of pragmatism, can offer distinctive advantages for researchers in this field. Mixed methods approaches, combining the strengths and minimizing the weaknesses of positivist and phenomenological paradigms, are discussed. Though traditionally qualitative and quantitative approaches were seen as being in opposition, increasingly they are being used in combination in various fields. However, this mixed methodological approach remains relatively rare in literature investigating the hospitality industry. In order to understand the potential benefits for this field, the philosophical and institutional context of mixed methods approaches are described, along with a review of recent literature supporting mixed methods research design in general, and in hospitality research in particular. Keywords: Methodology, mixed model design, qualitative approach, quantitative approach, hospitality industry 1. Introduction Choosing the right methodology for a given research project can be an enormous challenge. The selection of appropriate research tools requires careful consideration at each stage of the process, and must be tailored to various factors, including the objects of investigation and the type of research problems involved (Creswell, 1994; Newman and Benz, 1998). In some cases, the questions at hand may call for a combination of different methodologies (Yin, 1993; Newman and Benz, 1998; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 1998)—all of which will be dictated to some extent by the larger research paradigm, which in turn may be influenced by the research process itself. Ultimately, as Burrell and Morgan (1979) have observed, subscribing to a given research paradigm can be seen, to some extent, as an act of faith. While the positivist paradigm has tended to dominate in tourism and hospitality research, there is an increasing recognition of the value of phenomenological or more subjectively-based investigation. This is perhaps especially so in an industry where success depends upon the ‘human factor’: employees’ emotional labour and customers’ affective investment in the services offered. This paper summarizes some of the issues at stake in positivist and phenomenological research paradigms, and argues that a mixed-methods approach, combining the strengths of both paradigms, is especially appropriate to research in the hospitality and tourism industry. 128 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) 2. Research and Philosophical Paradigms A researcher’s paradigm or worldview necessarily exerts a certain force on the choice of research methods (Ben Letaifa, 2006).As Pansiri (2005) notes, while hospitality research depends on such a philosophical orientation and the assumptions that flow from it, this aspect of research often remains under-articulated in the existing literature. In this light, it is worth reviewing some of the philosophical questions entailed by the research process. At the heart of the discourse surrounding social science research methods lie the most profound ontological and epistemological questions, with implications for our attitudes and beliefs about human nature itself (Ben Letaifa, 2006). First and foremost, a research philosophy reflects certain guiding assumptions about the nature of the world, along with our own access to, or knowledge of, that world (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Lowe, 1991; Blaikie, 1993; Hussey and Hussey, 1997). The philosophy of science can be divided into two major areas. Ontology, or the science of being, poses questions about ‘what is’—that is, questions involving the nature and content of existence, including social and political reality, and the kinds of interactions that shape that reality (Blaikie, 1993). Also known as ‘first philosophy’, ontology encompasses essential questions about reality and existence and their functioning. Epistemology, the science of knowledge, is concerned with ‘how we know’, and probes the nature and limits of human knowledge. As Guisepi (2007) observes, the answers to such questions are vital for determining the credibility of scientific inquiry, because the answers provide the foundations for all possible knowledge. Ben Letaifa (2006) points out that such epistemological questions correspond, necessarily, to our ontological assumptions about the reality under investigation. In other words, questions of how we know intersect with questions concerning what sorts of things there are to know about. Epistemological approaches vary widely, and have split in different directions over the past half-century in the work of philosophical schools like post-positivism (critical realism) (see Manicas and Secord, 1982; Denzin, 1989; Denzin and Lincoln, 1994), pragmatism (see Howe, 1988; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 1998, Creswell, 2003) and postmodernism (see Lyotard, 1984; Rosenau, 1992; Denzin, 1993). The two major paradigms adopted in research, positivist and phenomenological approaches, both encompass a range of ontological and epistemological assumptions. In order to better understand the philosophical stakes for researchers, it is worth looking at these two approaches in greater depth. 3. Positivist and Phenomenological Research Paradigms ‘The key idea of the positivist paradigm is that the social world exists externally, and that its properties should be measured through objective methods, rather than being inferred through sensations, reflections or intuition’ (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Lowe, 1991: 22). Positivism, which emerged from the work of 19th century French philosopher Auguste Comte, defines knowledge in terms of empirically verifiable observation. This paradigm, at the heart of the scientific method, has traditionally dominated in research in social, behavioural (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2003) and organisational sciences (Ben Letaifa, 2006). In this view, ontologically speaking, the world is considered an external object of investigation, separate from the subjective experiences of the researcher—that is, it entails a realist position, in which the researcher’s goal is to gain knowledge of an external reality. Hence positivism favours methodologies such as statistical investigation that eschew a strong subjective inflection (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Lowe, 1991). The epistemological corollary to this world view that knowledge, for positivism, is limited to only those phenomena that can be observed, measured, recorded, etc (Blaikie, 1993; Hussey and Hussey, 1997). Phenomenology takes more or less the opposite approach, positing a view of reality as wholly constructed, subjective and social in nature. With an ontology based in the notion of social construction—that is, that the nature of reality and existence is determined by one’s subjective actions 129 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) and viewpoint, and not (or not only) the other way around—this approach entails an epistemology that seeks knowledge through the social ‘meaning’ of phenomena, rather than their measurement (EasterbySmith, Thorpe and Lowe, 1991; Blaikie, 1993; Hussey and Hussey, 1997). In 20th century philosophy, the split between ‘analytic’ and ‘continental’ scholarly traditions— which hew to more positivist and phenomenological priorities, respectively—reflects these same anxieties about the nature of the world and of human knowledge. As we shall see below, an attempt to bridge the gap can be found in the philosophical school of pragmatism. Table 1: The Key Features of the Positivist and Phenomenological Paradigms (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Lowe, 1991). Basic Beliefs: Researcher should: Preferred methods Positivist paradigm The world is external and objective Observer is independent Science is valuefree Focus on facts Look for causality and fundamental laws Reduce phenomena to simplest elements Formulate hypotheses and test them Operationalising concepts so that they can be measured Taking large samples include: Phenomenological paradigm The world is socially constructed and subjective Observer is part of what is observed Science is driven by human interests Focus on meanings Try to understand what is happening Look at the totality of the situation Develop ideas from induction from data Using multiple methods to establish different views of phenomena Small samples investigated in depth or over time Although the two approaches appear to be mutually exclusive in principle, in practice even the most staunchly positivist research is bound, to some extent, by subjectivity and ‘intersubjectivity’ or the ethics of dealing with others (Ben Letaifa, 2006). There has long been disagreement among researchers over the most appropriate paradigm, and even within one or the other paradigm, philosophers’ opinions can vary widely and continue to change and evolve (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Lowe, 1991). Increasingly, however, the opposition between the two can be seen as a false dichotomy, representing two sides of the same coin rather than an intractable conflict. In this spirit, many researchers today adopt a hybrid approach that seeks to benefit from the strengths and minimize the weaknesses of each methodological approach. 4. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches Qualitative research methods normally entail reasoning from induction (Neuman, 1997), gathering data and drawing conclusions from a multiplicity of interpretations and perceptions, beginning with observation, rather than a single, objective truth or rationality. It is normally associated with qualitative methods of research (Neuman, 1997). Quantitative approaches are generally based on the logic of deduction, beginning from accepted theories or premises and testing them rationally. Science in quantitative approaches is associated with objective truth, while qualitative research tends to focus on subjective experience (Neuman, 1997; Newman and Benz, 1998). As the term ‘qualitative’ suggests, such research is thus bound up with the quality of various people’s (subjective) experiences—and hence it often incorporates anecdotes and comparisons to shed light on people and scenarios under investigation. It is normally seen as seeking deeper understanding of a given phenomenon, whereas quantitative methods are more concerned with relationships of causation between phenomena (Ben Aissa, 2001). Quantitative methods are thus distinguished by numbers, statistics, and abstracting from data on sample populations to understand vastly larger groups (Denzin and Lincoln, 1994). The distinction has been neatly summarized as follows: 130 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) ‘Qualitative researchers use ethnographic prose, historical narratives, first-person accounts, still photographs, life histories, fictionalized facts, and biographical and autobiographical materials, among others. Quantitative researchers use mathematical models, statistical tables, and graphs’ (Denzin and Lincoln, 1994: 6) The difference between qualitative and quantitative can also be understood in terms of internal and external validity, respectively. It has been argued that development and validation are generally easier in the case of quantitative research, while their more generalisable nature and strict limits of inquiry afford greater external validity to these types of studies (Ben Letaifa, 2006; Newman and Benz, 1998). Qualitative approaches, on the other hand, grant far more flexibility to the researcher, while the in-depth focus of research implies a greater internal validity (Newman and Benz, 1998; Ben Letaifa, 2006). For a comparison of the approaches associated with each style of research, see Table 2 (Neuman, 1997: 329). Table 1: Distinctions between qualitative and quantitative approaches (Neuman, 1997: 329) Quantitative style Measure objective facts Focus on variables Reliability is key Value free Independent of context Many cases, subjects Statistical analysis Researcher is detached Qualitative style Construct social reality, cultural meaning Focus on interactive processes, events Authenticity is key Values are present and explicit Situationally constrained Few cases, subjects Thematic analysis Researcher is involved 5. The Paradigm Wars and Social Sciences Research For most of the past century, quantitative methods have widely been considered dominant (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2003). In tourism and hospitality research, quantitative approaches remain at the forefront, in part because a management research perspective is normally adopted, favouring a ‘natural scientific approach to organizational life’ and normally entailing large sample statistical studies (Pansiri 2005: 192). Fields like business and management studies (Werner, 2002) and psychology (Smith and Brain, 2000), in which tourism research has roots, also tend to retain an emphasis on quantitative methods. Nevertheless, as Ben Aissa (2001) has noted, qualitative approaches have been gaining ground in recent years, as an alternative to research based on solely on statistical and causal correlations, and addressing some of the limits of such tools for understanding increasingly complex organisational structures. The social and behavioural sciences are still, in some sense, emerging from what Tashakkori & Teddlie (1998: 4) have dubbed the ‘paradigm wars’—a perennial and often heated dispute among researchers over qualitative and quantitative methods and their relative assets and drawbacks in different applications. The growing consensus among researchers seems to acknowledge the complementary, rather than oppositional, nature of these two types of research, with the ultimate decision on methods to be dictated by the tools available for, and most appropriate to, a given study (Trochim, 2006). ‘Each data-gathering method has its own distinct advantages as well as disadvantages; however, when used in conjunction with another, the disadvantages of one method can generally be offset by the advantages of the other(s).’ (McClelland, 1994: 7) In the social and behavioural sciences, including tourism and hospitality research, field studies are invaluable for probing the human needs and motivations behind the numbers. There has been much recent work emphasizing the pointlessness of the qualitative-quantitative controversy for field researchers, emphasizing instead the diversity of tools available to collect and analyze data (for 131 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) example, Creswell, 2003; Creswell et al, 2003; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2003; Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Creswell, Trout and Barbuto ,2007; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2008; Bergman, 2008; Plano Clark et al, 2008; Hesse-Biber, 2009). Today, in the aftermath of the paradigm wars, there has arisen what Tashakkori & Teddlie term a ‘third methodological movement’, a ‘pragmatic way of using the strengths of two approaches’ (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003: ix). Such an approach has gone by different names, including ‘mixed methods’, ‘combined’, ‘integrated’, and ‘multimethod’ research (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003: ix). In all cases, this highly pragmatic approach to research favours drawing upon all the tools suited the job at hand. As we have seen, the philosophical paradigms underpinning qualitative and quantitative research—the positivist and phenomenological worldviews described above—at first appear incompatible. In this light, a growing number of scholars (e.g., Pansiri, 2005; Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004) have argued that an orientation based in philosophical pragmatism offers a solid ontological and epistemological basis for mixed methods research, combining the benefits of each approach in a single study. Before looking at this philosophical orientation in greater depth, it bears outlining some of the strengths and weaknesses of mixed model research design. 6. Toward Mixed Model Design as an Approach Mixed methods research encompasses a range of approaches in which qualitative and quantitative tools are combined, either sequentially or in tandem (Creswell et al, 2003, Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998), and indeed, the two are often integrated throughout the process of research (Creswell et al, 2003, Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998). In the past ten years, there has been an increasing push to formalise the combination under the rubric of ‘mixed methods’ research design. Such research points to the complementary roles each style of research can play. An understanding of this approach may be considered indispensible to contemporary investigators: ‘Regardless of the field of study, researchers should begin by securing for themselves a good introduction to the issues of mixed methods research’ (Creswell, Trout, and Barbuto, 2007: 20). Consider the following definition of mixed-methods research: ‘A mixed methods study involves the collection or analysis of both quantitative and/or qualitative data in a single study in which the data are collected concurrently or sequentially, are given a priority, and involve the integration of the data at one or more stages in the process of research.’ (Creswell et al, 2003: 212) Simply put, combining qualitative and quantitative methods can yield more useful and valid results, offering different perspectives on the same phenomenon and offering a greater overall understanding of the topic. Two practical reasons can be put forward to support the use of combined methods: ‘The first is to achieve cross-validation or triangulation – combining two or more theories or sources of data to study the same phenomenon in order to gain a more complete understanding of it. The second is to achieve complementary results by using the strengths of one method to enhance the other.’ (Sale et al, 2002: 47) Along the same lines, mixed methods have been embraced because: • ‘can answer research questions that the other methodologies cannot. • provides better (stronger) inferences. • provides the opportunity for presenting a greater diversity of divergent views’ (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2003: 14-15). 132 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) In other words, the effect of combining research methods can be not only additive, but transformative, such that the results yielded by both methods can be ‘greater than the sum of their parts.’ This is especially so when the two are used in a complementary way, and in combinations that minimize the weaknesses or limitations of a given method (Creswell, 1994, Morgan, 1998; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998; Creswell, 2003; Creswell et al, 2003; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2003). Such an approach can guarantee greater validity of the research results (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998; Threlfall, 1999; Sale et al, 2002; Nakkash et al, 2003; Ben Letaifa, 2006). Table 2: Mixed Methods Design types (Creswell et al, 2003: 224). Design Type Sequential explanatory Sequential exploratory Sequential transformative Concurrent triangulation Concurrent nested Concurrent transformative Implementation Quantitative followed by qualitative Qualitative followed by quantitative Either qualitative followed by quantitative or qualitative followed by quantitative Concurrent collection of quantitative and qualitative data Concurrent collection of quantitative and qualitative data Concurrent collection of quantitative and qualitative data Priority Usually quantitative; can be qualitative or equal Usually qualitative; can be quantitative or equal Quantitative, qualitative, or equal Preferably equal; can be quantitative or qualitative Quantitative or qualitative Quantitative, qualitative, or equal Stage of Integration Interpretation phase Interpretation phase Interpretation phase Interpretation phase or analysis phase Analysis phase Usually analysis phase; can be during interpretation phase Though mixed methods research is admittedly an approach ‘still in its adolescence’ (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003; x), it offers intriguing possibilities that make it: ‘a rich frontier that will allow science to explain a significant percentage of a given phenomenon, while also remaining open to discovering critical issues embedded in or surrounding that phenomenon’ (Creswell, Trout, and Barbuto, 2007: 19) As noted, the umbrella term ‘mixed methods’ encompasses a range of approaches. Perhaps most common in the social sciences is research encompassing multiple stages, also known as ‘sequential’ or ‘two-phase’ studies. Because phenomenological or qualitative research is most effective as a mode of ‘theory building’ (Newman and Benz, 1998: 20) or ‘theory generation’ (Punch, 1998: 16), such an approach is commonly used in an initial or exploratory phase, to explore the problem at hand and formulate questions to be addressed in the next stage (see Table 1). Other approaches include ‘dominant/less dominant’ research design, later termed ‘priority’ (Morgan, 1998) or ‘nested’ (Creswell et al 2003) research, in which overall research is conducted using one method primarily, with the alternative methodology employed for a smaller element of the study. Finally, ‘mixed methodology’ denotes research design that integrates qualitative and quantitative approaches during the entire process of research. Creswell et al (2003) further elaborate a typology of mixed methods research, based on factors like data collection sequence, the weight accorded to each methodological approach, and the stage(s) of research at which the two are integrated. For an overview of various types of mixed methods research design, see Table 3. 133 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) Table 3: Strengths and Weaknesses of Mixed Research (Adapted from Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004: 21). Strengths • Words, pictures, and narrative can be used to add meaning to numbers. • Numbers can be used to add precision to words, pictures, and narrative. • Can provide quantitative and qualitative research strengths. • • Researcher can generate and test a grounded theory. Can answer a broader and more complete range of research questions because the researcher is not confined to a single method or approach. • A researcher can use the strengths of an additional method to overcome the weaknesses in another method by using both in a research study. • Can provide stronger evidence for a conclusion through convergence and corroboration of findings. Can add insights and understanding that might be missed when only a single method is used. Can be used to increase the generalizability of the results. Qualitative and quantitative research used together produce more complete knowledge necessary to inform theory and practice. • • • Weaknesses • Can be difficult for a single researcher to carry out both qualitative and quantitative research, especially if two or more approaches are expected to be used concurrently; it may require a research team. • Researcher has to learn about multiple methods and approaches and understand how to mix them appropriately. • Methodological purists contend that one should always work within either a qualitative or a quantitative paradigm. • More expensive. • More time consuming. • Some of the details of mixed research remain to be worked out fully by research methodologists (e.g., problems of paradigm mixing, how to qualitatively analyze quantitative data, how to interpret conflicting results). Unfortunately, the popularity of mixed methods research ‘has been retarded to date by the vestige of the paradigm war's (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998; x).Such studies can also be very labourintensive, placing a high demand on the researcher—who requires expertise in both types of method— and their lengthy nature generally makes them unsuitable for publication in journals (Creswell, 1994). Nevertheless, there is evidence that mixed methods will eventually become the standard methodological approach in the social and behavioural sciences (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003), with leading researchers calling for greater use of mixed methodologies in organisational and management studies in particular (Creswell, Trout and Barbuto, 2007). A quarterly SAGE publication entitled ‘Journal of Mixed Methods Research,’ in which mixed methods research studies are take centre stage, testifies to the growing relevance of this approach. 7. Implications for the Hospitality Industry As noted, quantitative research has tended to dominate in the literature on the hospitality industry. This is due in part to the management research perspective that dominates the field. A study by Mendenhall et al (1993) found that, from 1984 to 1990, only 14 percent of articles in the International Journal of Management used qualitative approaches, and just 4 percent used combined methodologies. Sandiford and Seymour (2007: 725) also bemoan the relative dearth of qualitative approach in hospitality research; they note that ‘most hospitality sector-specific journals carry few examples of this approach,’ despite the fact that ‘other academic publications have reported ethnographic investigations of various aspects of hospitality’ —that is, researchers from other fields have emphasized such an approach in 134 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) investigating hospitality-specific problems, with examples ranging from pub workers’ emotional labour to older restaurant patrons’ usage patterns. In this light, the authors warn that a continued emphasis on quantitative investigation within hospitality literature risks isolating the field from the wider discourse community of social sciences researchers. ‘If such work is not equally valued by hospitality journals,’ they note, ‘there is a danger that researchers could be discouraged from sharing their work with the hospitality community, and that hospitality research could be marginalized’ (725). In this light, according to Pansiri, ‘discussion of research philosophies as they apply to tourism research can no longer be neglected’ (2005: 192). Fortunately, today there is increasing diversity of methodologies in tourism research as investigators recognize the benefits of ‘soft’ or qualitative approaches in understanding the human relations at the heart of this industry. The author’s own recent research study (Masadeh, 2009) used a two-stage mixed methods research approach—a sequential exploratory strategy—to complete a unique investigation of middle management training in international hotel chains in Jordan. In this case, because the research topic was largely unexplored, an initial qualitative (focus group) phase proved extremely productive for gathering initial data and formulating items for the second, quantitative, phase (a questionnaire). This experience supported the notion of mixed methods as a means for producing a comprehensive perspective of an unexplored topic (Tashakkori & Teddlie 1998). Because a field like tourism studies is so interdisciplinary in scope—with its origins cobbled together from psychology, geography, political science, law, and so on—it tends to lack philosophical cohesion or even, often, a well-articulated philosophical perspective. ‘While the issue of mixing methods is emerging in tourism,’ Pansiri (2005: 198) notes, ‘very few authors have attempted to link the debate to philosophical issues’. Intriguingly, the author develops the argument that a pragmatist philosophical orientation offers the ideal perspective from which to approach the problems of tourism research, providing a strong ontological and epistemological foundation for a mixed-methods approach in this field, just as it has begun to be recognized as such in other areas of research. Similarly, , Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) make the case that pragmatism, despite some of its philosophical limitations, offers a bridge between ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’, or quantitative and qualitative, philosophical orientations, precisely because it does not allow for any notion of their incompatibility. That is, pragmatism rejects ontological or epistemological abstractions in favour of ‘what works.’ Pragmatism has been hailed as the best paradigm for justifying the use of mixed-methods research (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 1998; Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2003; Rallis and Rossman, 2003) since it considers the research question to be more important than either the method used or the paradigm that underlies the method (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 1998; Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2003). At the core of pragmatism is a rejection of the dichotomy between positivist scientism and antipositivist subjectivism (or ‘positivist/functional’ and ‘interpretive’ positions), positing instead a version of ‘truth’ that is measured by its effectiveness, on the ground, in solving actual human problems—that is, the ‘truth’ is that which works. Truth is thus seen as socially constructed to a large extent, yet it may still be investigated empirically to the extent that these results prove of practical use. In hospitality industry research, mixed methods approaches are gaining ground, and may prove especially appropriate because of the way they allow the researcher to probe the ‘soft’ aspects of organisational development without sacrificing scientific rigour. 8. Conclusion Mixed methods research, drawing on the benefits of qualitative and quantitative approaches, is becoming increasingly popular among researchers in a wide variety of fields. Although the approach is relatively new, mixed method research design—in its many current forms, and those yet to be explored—holds enormous promise as an antidote to the paradigm wars. Although positivism remains dominant in some areas, this approach stands to benefit from the insights of a more phenomenological perspective. This is especially pertinent in a field like the hospitality industry, where positivist 135 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) approaches have dominated, often at the expense of understanding the crucial human factors at play in an organisation’s success. Ultimately, mixed methods research provides intriguing possibilities for tailoring research design to the problem under investigation. In this light, mixed-methods research can also offer researchers an often-overlooked opportunity to examine the ontological and epistemological premises underpinning their work. References [I] Ben Aissa, H (June 2001) "Quelle méthodologie de recherche appropriée pour une construction de la recherché en gestion ?" XIème Conférence Internationale de Management Stratégique. Held June 13-15 2001 at Laval Univeristy. Laval: Laval University Press: 27 p [2] Ben Letaifa, S. (2006) Compatibilité et incompatibilité des paradigmes et méthodes [online] available from < http://www.strategie-aims.com/actesateliers/Quali06/BenLetaifa.pdf > [14 April 2011] [3] Bergman, M.M. (2008) Advances in Mixed Methods Research: Theories and Applications. Sage publications: London [4] Blaikie, N. (1993) Approaches to Social Enquiry. Cambridge: Polity Press [5] Brannen, J. (1992) "Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: an overview." In Mixing Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Brannen, J (ed.) Aldershot: Avebury: 3-37 [6] Burrell, G., Morgan, G. (1979) Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis. Heinemann Educational Books: London [7] Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., Gutmann, M. L., and Hanson, W. E. (2003) "Advanced mixed methods research designs." In Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Tashakkori, A., and Teddlie, C (ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage: 209-240 [8] Creswell, J.W. (2003) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [9] Creswell, J. W. (1994) Research design: qualitative & quantitative approaches. California: Sage [10] Creswell, J.W., Trout, s., and Barbuto, J. (2007) A Decade of Mixed Methods Writings: a Retrospective [online] available from the Academy of Management Online website <http://division.aomonline.org/rm/2002forum/retrospect.pdf> [14 May 2007] [II] Denzin, N. (1989) The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 3rd edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall [12] Denzin, N. (1993) "Where has postmodernism gone?" Cultural Studies 7, (3) 507-14 [13] Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln,Y.S. (1994) Handbook of Qualitative Research (ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage [14] Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R. and Lowe A. (1991) Management Research: an Introduction. London: Sage [15] Fortier, D. (2002) entre l’humain et la réalité: Comment distinguer le vrai du faux? [online] available from <http://aladin.clg.qc.ca/~fortid/index.html> [11 March 2011] [16] Guisepi, R (2007) Philosophy: An analysis of the grounds of and concepts expressing fundamental beliefs[online] available from <http://history-world.org/philosophy.htm> [12 March 2011] [17] Hesse-Biber, S.N. (2009) Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice. Guilford Publications: New York [18] Howe, K.R. (1988) "Against the quantitative-qualitative incompatibility thesis or dogmas die hard" Educational Researcher 17, 10-16 [19] Hussy, J. and Hussy, R. (1997) Business Research: a Practical Guide for Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students. Basingstock: Macmillan Business 136 European Journal of Social Sciences – Volume 28, Number 1 (2012) [20] Johnson, R. B., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004) "Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come." Educational Researcher 33, (7) 14–26 [21] Lyotard, J.F. (1984) The Postmodern Condition. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press [22] Manicas, P. and Secord, P. (1982) "Implications for psychology of the new philosophy of Science." American Psychologist 38, 390-413 [23] Masadeh, M. (2009) Human Resources in international hotel chains in Jordan: “Out-of-country” training determinants. Unpublished PhD thesis. Coventry University [24] McClelland, S. B. (1994) "Training Needs Assessment Data-gathering Methods: Part 4, On-site Observations." Journal of European Industrial Training 18, (5) 4-7 [25] Mendenhall, M., Beaty, D. and Oddou, G. (1993) "Where have all the theorists gone? An archival review of the international management literature." International Journal of Management, 10, (2) 146–53 [26] Morgan, D. (1998) "Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: Applications to health research." Qualitative Health Research 8, (3) 362-376 [27] Neuman, W. L. (1997) Social Research Methods - Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights. [28] Newman, I., and Benz, C. R. (1998) Qualitativequantitative research methodology: Exploring the interactive continuum. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press [29] Pansiri, J. (2005) "Pragmatism: A methodological approach to researching strategic alliances in tourism." Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 2, (3) 191-206 [30] Punch, K.F. (1998) Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [31] Plano Clark, V.L., Creswell, J.W., O’Neil Green, D., and Shope, R.J. (2008) "Mixing Quantitive and Qualitative Approaches: An Introduction to Emergent Mixed Methods Research" in Handbook of emergent methods. Hesse-Biber, S.N, and Leavy, P. (ed.) Guilford Press: New York [32] Rosenau, P. (1992) Postmodernism and the Social Sciences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [33] Sale, J. E. M., Lohfeld, L. H., and Brazil, K (2002) "Revisiting the Quantitative-Qualitative Debate: Implications for Mixed-Methods Research." Quality & Quantity 36, 43-53 [34] Sandiford, P.J. & Seymour, D. (2007) "A Discussion of Qualitative Data Analysis Hospitality Research with Examples from an Ethnography of English Public Houses." International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26, (3) 724 -742 [35] Smith, P.K., and Brain, P. (2000) "Bullying in Schools: Lessons from two decades of research." Aggressive Behavoiur 26, (1) 1-9 [36] Tashakkori, A., and Teddlie, C. (2003) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [37] Tashakkori, A., and Teddlie, C. (1998) Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [38] Tashakkori, A., and Teddlie, C (2008) Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage publications: London [39] Threlfall, K. D. (1999) "Using focus groups as a consumer research tool." Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science 5, (4) 102-105 [40] Trochim, M.K. (2006) The Qualitative-Quantitative Debate [online] available from <http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/contents.php> [13 May 2010] [41] Werner, S. (2002) "Recent developments in international management research: A review of 20 top management journals." Journal of Management 28, (3) 277-305 [42] Yin, R. K. (1993) Applications of case study research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage 137