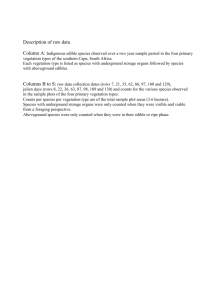

CHAPTER 9: ROADSIDE VEGETATION MANAGEMENT

advertisement