Naaman and His Leprosy

advertisement

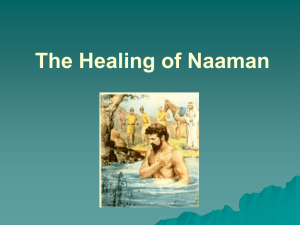

Bar-Ilan University Parshat Tazria-Metzora 5773/April 13, 2013 Parashat Hashavua Study Center Lectures on the weekly Torah reading by the faculty of Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel. A project of the Faculty of Jewish Studies, Paul and Helene Shulman Basic Jewish Studies Center, and the Office of the Campus Rabbi. Published on the Internet under the sponsorship of Bar-Ilan University's International Center for Jewish Identity. Prepared for Internet Publication by the Computer Center Staff at Bar-Ilan University. 910 Alexander Klein Naaman and His Leprosy – Faith and Good vs. Show of Power and Aggressiveness Most of the interpersonal relations in the story of Naaman and his affliction with leprosy are characterized by show of power and suspicion; communications are for the most part full of hatred, aggressiveness and overblown egos, with two exceptions: the kindly, concerned servants (the young girl in Naaman's house and his servants who accompanied him to the land of Israel) and the prophet Elisha. Let us follow how the story unfolds so that we can understand what it signifies. The young girl, servant to Naaman's wife, sets the plot in motion when she tells her about the prophet who is capable of curing Naaman from his leprosy. From that point on, the story progresses until Naaman is completely cured, although the road to this end is not entirely smooth or pleasant. Naaman reports to his master, the king of Aram, the rumor that has reached his ears, and the latter, instead of consulting the king of Israel and asking him if there is any substance to the rumor, sends him an aggressive letter by way of Dr. Klein teaches in the Math Department and at Ashkelon College. 1 Naaman: "Now, when this letter reaches you, know that I have sent my courtier Naaman to you, that you may cure him of his leprosy" (II Kings 5:6).1 The king of Aram takes the trouble to inform the king of Israel that Naaman is his courtier in order to establish the precise domestic and foreign hierarchy. The letter is harshly phrased as an order, not a request, and notes that Naaman has already set out on his way and will arrive without further advance warning. Nevertheless, the king of Israel is expected to carry out the order forthwith. Little wonder that the king of Israel was convinced this was nothing but a pretext for attacking him and his land: "He rent his clothes and cried, 'Am I G-d, to deal death or give life, that this fellow writes to me to cure a man of leprosy? Just see for yourselves that he is seeking a pretext against me!'" (II Kings 5:7). This is an extreme reaction of a frightened and suspicious person. He rends his clothes as a mark of mourning and refers to the king of Aram in hostile, hateful terms as "this fellow." It could well be that the king of Israel understood correctly the action taken by the king of Aram, for the young girl had told of "the prophet in Samaria" (II Kings 5:3) and had not mentioned the king of Israel. Perhaps the king of Aram was taking advantage of the situation in order to precipitate a diplomatic incident in which the people of Israel would pay the price for their "failings." At this point Elisha enters the picture. He turns directly not to Naaman but to the king of Israel: "Why have you rent your clothes? Let him come to me, and he will learn that there is a prophet in Israel" (II Kings 5:8). Elisha's objective is clear: to show the commander of Aram's army that in Israel the spiritual reality is different from what he has previously encountered. Naaman rides up to the prophet's house "with his horses and chariots"—symbols of his might and status,2 but to his astonishment and disappointment, Elisha does not come out to greet him. Instead, Elisha sends a messenger who relays to Naaman an instruction accompanied by a promise from the prophet: "Go and bathe seven times in the Jordan, and your flesh shall be restored and you shall be clean" (II Kings 4:10). Naaman apparently took offense in his own person and in the name of his country. He mentions the great rivers of Damascus and scoffs at the prophet's instructions, sending him to bath in Israel's miserable little river. 1 It follows from the scriptural text that Israel at the time was dominated by Aram. See Boustenai Oded, Encyclopedia Olam ha-Tanakh, II Kings, Tel Aviv 1994, p. 43. 2 The biblical collocation, "horse and chariot," expresses military might and domination. Deuteronomy 20:1, Joshua 11:4, I Kings 20:1, Isaiah 43:17, Ezekiel 39:20, and many others. 2 Cf. Later Naaman gives in to the imploring of his goodly servants, and to his great surprise he is completely cured in the water of the Jordan River. Henceforth he becomes a confirmed admirer of the prophet. His entire tone of voice changes: "Returning with his entire retinue to the man of G-d, he stood before him3 and exclaimed, 'Now I know that there is no G-d in the whole world except in Israel! So please accept a gift from your servant'" (II Kings 5:15). This was the opportune moment that Elisha had anticipated for publicly sanctifying the name of his G-d: "As the Lord lives, whom I serve, I will not accept anything" (II Kings 5:16). The prophet's opposition to deriving personal benefit from the outcome of his advice is like a fresh, pure breeze in the face of all the agitated egotistical maneuvering seen thus far. Naaman, who wisely understood who was the true G-d, apologized to Elisha for not being able to change his way of life from end to end. To continue being the commander of Aram's army he would have to behave hypocritically and worship pagan gods in the temple of Rimmon along with his king. In this regard, too, Elisha does not attempt to sway him or to reap tangible fruits, but very graciously departs, saying to him, "Go in peace" (II Kings 5:19). Elisha knows that whatever he says further will merely detract. The story ought to have concluded here, with this high point of all's well that ends well. Indeed, Naaman heads back home and going "some distance from him" (II Kings 5:19).4 But to the reader's great surprise, Elisha's attendant Gehazi appears on the scene. Lust for money seems to have gotten the better of Gehazi, and taking advantage of Naaman's excitement, he guilefully manages to get silver and clothes out of him. Of all people, it is the prophet's close attendant who knows him and his wonders well who cannot control his urge! At this point the prophet's words become scathingly bitter. He realizes that Gehazi is not only acquisitive but also a liar who denies his actions. Therefore he assaults Gehazi with rhetorical questions: "Did not my spirit go along when a man got down from his chariot to meet you? Is this a time to take money in order to buy clothing and olive groves and 3 In several scriptural sources the expression "to stand before" signifies submission and acceptance of authority. Cf. Deut. 4:10, 10:8; Judges 20:28; I Kings 17:1, 18:15; II Kings 3:14, and many others. Here, too, Elisha describes himself as standing before the Lord (verse 16, although the New JPS Translation renders the Hebrew as "whom I serve"). 4 There is an illusory ending here, for the experienced reader, who knows that one way of concluding a biblical story is to have the hero return to his home, assumes that the story is done, although this is not the case. 3 vineyards, sheep and oxen, and male and female slaves?" (II Kings 5:26). The story ends with Elisha cursing Gehazi and his progeny: "'Surely, the leprosy of Naaman shall cling to you and to your descendants forever.' And as [Gehazi] left his presence, he was snow-white with leprosy" (II Kings 5:27). One has the impression that the very leprosy that had been in Naaman's body took wing and landed on Gehazi's body. The reversal of fate that takes place in the story, from Naaman having leprosy to "the leprosy of Naaman" afflicting Gehazi, proves that good character, faith, and truth are a person's best guarantee for a proper, healthy life. Translated by Rachel Rowen 4