Information On Parliamentary Debate

advertisement

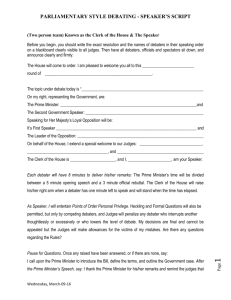

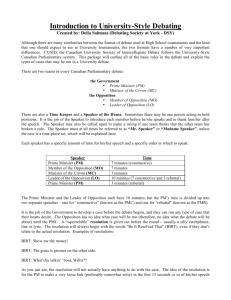

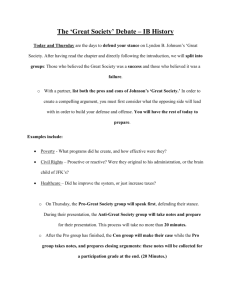

Information On Parliamentary Debate Adapted from information prepared by Diane Greenfield, Mount Holyoke College Parliamentary Debate Team, 1991 General Parliamentary debate is a formal contest of wit and rhetorical skill which theoretically occurs in a House of Parliament. Participants are the Government and Opposition teams, and the moderator is Madam or Mister Speaker of the House. A resolution is a sentence or phrase which provides the subject a debate. The Government team has ten minutes to prepare a case centered around this topic. Two types of speeches exist in a round, constructives and rebuttals. The order of speakers is as follows: A. Prime Minister B. Leader of the Opposition C. Member of the Government D. Member of the Opposition E. Leader of the Opposition F. Prime Minister OR A. Prime Minister B. Member of the Opposition C. Member of the Government D. Leader of the Opposition E. Prime Minister 8 min 8 min 8 min 8 min 4 min (rebuttal) 4 min (rebuttal) 8 min 8 min 8 min 12 min 4 min The latter form is rarely used, and it will be communicated by the position writing “no split” on the board, indicating that they will not split the second speech and rebuttal. The purpose of the constructive speeches is to introduce the case arguments for and against it. The rebuttal will summarize the major points and responses, and no new arguments will be submitted. The remaining four minutes of the Leader’s speech in the alternate form comprises the Opposition rebuttal. Judges should time the speeches, providing hand signals for the speakers or allow debaters to time themselves. It is the Speaker’s responsibility to see that speech lengths are observed strictly, though a 15 second grace period is allowed at the end of every speech. Responsibilities of Debaters Government It is the responsibility of the government to define and defend the resolution in a manner which makes it debatable. The Government has the option to run the resolution “straight” (meaning they argue the theoretical basis of the actual resolution), or they may ”link” it to a case in terms of the exact wording of the resolution. Types of Cases A. Need/Plan/Benefit: This is the most common approach. The government asserts that a given group must do something to improve the status quo. Cases are usually in the form of political/social problems, but they may also be hypothetical syllogisms (if X, then Y) Examples are: 1. 2. 3. “Seat belts should be installed on school busses.” “ Puerto Rico should become a state” “If the lost city of Atlantis is found, it should be raised” B. Value/Comparison: Two related objects or ideas are compared and contrasted, or a moral/practice advantage is placed upon one item. Examples are: 1. 2. “Silk flowers are better than real flowers’ “Capitalism has failed” C. Time/Space: Both judges and teams assume the role of a figure in an alternate spatiotemporal setting. Consequently, all facts and judgements must be of this time period. Any information which would be unknown to people of this setting is unacceptable. Run these cases at your own risk. Please avoid mere silliness and stupidity. Position It is the responsibility of the opposition to clash with the governments case. This must be done by both establishing an opposing philosophy and a point by point analysis of the government’s major arguments. The opposition generally, but not exclusively, accomplishes this task by following one of four formats: Defense of the status quo: the governments plan is ludicrous, the present system is not in need of repair, and any change will harm it. Minor repairs: The governments plan is a reasonable one, but will be, in the end, ineffective. In other words, the present an is such that changes suggested by the affirmative side will have no significant impact on the status quo. Counter Case: The present system is in need of repair, but the position’s suggestion will accomplish this task more effectively than the Governments plan. All counter cases must deal directly with the subject outlined by the Prime Minister. Reverse Comparison: The Government proposes a case in which the Opposition side is inherent in its definition. Therefore, the position seeks to prove the exact negative of the propose. This approach is common in value/comparison cases, but the government should avoid forcing the opposition to argue a morally repugnant position(such as “Child abuse is good”) Brief Description of each Speech Prime Minister constructive: Defines the resolution and establishes a link to the case. S/he also outlines major points supporting the Government philosophy. Opposition constructive: Outlines the Opposition’s major philosophy. If irregularities existed in the proposal, they must be mentioned within the first three minutes of the speech, or the government’s case shall carry through the entire round, regardless of further complaints. Government: Supports the Prime Minister and introduces new points. Opposition: Supports the Leader Opposition and introduces new points. Opposition rebuttal: Summarizes major Opposition points and philosophy. May not introduce new arguments. Prime Minister rebuttal: Challenges points introduced by the Member Opposition, but may not introduce new ones. Summarizes and reinforces the original case. Responsibilities of the Speaker The Speaker of the House (the primary judge) moderates the debate, and is therefore in charge of running the debate itself. The speaker should do the following in this order: 1. When each team enters the room, ask them to write their names and team number on the board if they have not already done so. Make sure they write the resolution on the board. 2. Allow the government 10 minutes to prepare the case. Rounds should begin 15 minutes after the announcement of the resolution, and teams should be in the room at that time and ready to debate. 3. Call the House to order: “I now call this House to order and recognize the Prime Minister to deliver a speech not to exceed eight minutes on the resolution ____________” 4. After the Prime Minister finishes: “I thank the Prime Minister and recognize the Leader of the Opposition to deliver an eight minute constructive against the proposition.” 5. Continue until all constructives are complete, then: “I would now like to recognize the Leader of the Opposition to deliver a four minute rebuttal , and I would like to remind the Leader that no new arguments are permissible, but new examples are welcome.” 6. Following the Opposition rebuttal: “I thank the Leader of the opposition and recognize the Prime Minister to deliver the final four minute rebuttal, and would like to remind the Prime minister that no new arguments are permissible, but new examples may” These phrases are just examples, and you don’t have to read them verbatim. When the debate is over, thank both teams and ask them to leave the room so you can fill out your comments or points while debaters are in the room, and, under NO circumstances, reveal your decision or provide constructive comments after the round. 7. Fill in the overall speaker/team points winner and make constructive, educational comments. Sign the white form. 8. Return the completed ballot to the ballot table as soon as possible, especially important during rounds I through IV, when we’ll need results to power match. During round I-IV you will most likely be doing back-to-back judging, so be sure to look for a ballot for the next round. Example of Case Derivation From a NPDA Resolution If the general topic of debate was the phrase “I think, therefore I am”, then the debaters have several options as to how they wish to pursue this resolution. A. Running the resolution “straight”. 1. Construct a case demonstrating how, on a philosophical level, the only thing that we absolutely know to be true is that we think. 2. This case would undoubtedly require some familiarity with the background of the philosopher who made the statement, Rene Descartes. B. Linking a case to the resolution. 1. Need/plan/benefit case: Argue that “I think, therefore I am” is actually asking us about the value of education. An appropriate subject area for debate, given the wording of the resolution, might be for the government to argue that it should be mandatory for citizens of the United States to complete a high school degree, given our current exceedingly high drop out rates. They could demonstrate how economic productivity would increase, and how an educated citizen is a happy citizen. 2. Value/comparison case: Construct a case demonstrating that “Making decisions from thought is better than making decisions from instinct.” 3. Time/space case: Ask the judge to act as the first superintendent of a regional school system in the 1930’s. The government team could be two angry parents who wish the school system would make middle school education compulsory, and the opposition team would play the opposite role of two parents who want to allow their children to drop out of school in order to work. C. In either case, negative ground is fairly clear. 1. Running the resolution “straight”: Argue that we do know more than just the fact that we think, providing the appropriate philosophic support. 2. Need/plan/benefit scenario: Argue that forcing students to go to high school would result in a poor learning atmosphere, and that valuable manual labor and vocational technology potential would be lost. Argue that educated citizens aren’t happy. 3. Value/comparison round: Argue that instinct and intuition are often better than reason for making decisions. 4. Time/space round: Demonstrate that it is more valuable to have teenagers as members of the work force during the Great Depression than as members of a high school. No matter how the government chooses to define the round, both teams should strive to ensure that they choose topics of argumentation that are interesting, debatable and fair to both teams. Points of Information: Common in British style parliamentary debate, points of information are questions aimed at the opposing team/speaker during their constructive speeches. Functioning much like crossexamination (but without the structured time period), their object is to test the wit, nerve, and rhetorical skill of an opponent. 1. Points of information may be offered only after the first minute and before the last minute of the four constructive speeches. Points of information should be phrased as questions and may not exceed 15 seconds. 2. At his or her absolute discretion, the member holding the floor (the one delivering the constructive speech) may yield to an opponent for a point of information. 3. The member wishing to make the point of information rises, places his or her hand atop his or her head, and asks the member holding the floor to recognize him or her (usually by saying “Point of information, sir/madam”). The member holding the floor may yield the floor to the question (“I’ll take your point, sir/madam”) or may disallow the point (“Not at this time, sir/madam”). 4. After being recognized, the member making the point of information has a maximum of 15 seconds to ask a question of his or her opponent. The member making the point then yields the floor to the original debater who must answer the question and continue on with his or her speech. 5. Judges will evaluate debaters on their ability to propose points of information and to handle answering the questions. Debaters should be careful not to take so many points that the flow and organization of their speech is impaired. Refusing all points of information is also negatively evaluated. Debaters who are able to skillfully integrate the answers to a point of information within the context of their speech should be rewarded. NPDA POINT SCALE GUIDELINES Rate the speech as a whole or fill in the individual categories e.g. Content, refutation); remember that the average speech should receive 23 points. This means that someone who receives a ‘4’ in each category will be slightly above average, someone who receives a ‘3’ in each category is significantly below average. A speaker who receives a ‘26’ in each round, (‘4’ in most categories, “5’ in a couple will probably get a speaker prize. Below 15 Very poor or offensive speech 15-18 Poor speech, noticeable weak in most areas, fails to deal with arguments, ill-delivered 19 Fair in a couple of areas, several glaring deficiencies. 20 Passable, but with one or two major problems 21 Still not a good speech, but not abysmal 22 Below average, but barely 23 No glaring flaws or delivery problems, but no extraordinary characteristics 24 Slightly above average; solid in all areas 25 Very good speech. Solid in all areas, excellent in at least one 26 Very, very good speech. Articulately delivered, solidly argued, with strong analysis 27 Excellent speech. Outstanding in either style or argument, and at least very good in the other 28 Phenomenal speech; leaves an impression; dominates round 29 Absolutely tremendous, essentially flawless 30 Best Speech you have ever heard WHAT TO LOOK FOR AS A JUDGE 1. The two main categories you shall consider are argumentation and style. In general, arguments weigh approximately 65% of the weight in a decision with style as 35%. Thus, in a close round, the winner should be the team presenting the more logical points. 2. The arguments should be presented in an organized manner. Ideally, you should be able to follow your flow straight down and have all speakers hit major points in the same order. 3. Debaters should be talking to YOU and not the other team. Eye contact is important. 4. Debaters should not carry anything (pens, pencils, etc.) except for their flow pad to the lectern, and they should not place their hands in pockets. These two rules are minor and due to the traditions of parliamentary debate. However, it is important to understand that delivery is very important in parliamentary debate. Use of jargon and speed, and sloppiness in stance, etc. should not be overlooked as they are for CEDA debate. 5. Variety in cadence, gestures, wit and humor, etc. will positively affect stylistic considerations. 6. Heckles are allowed and even encouraged, but they should be short, witty, and to the point. 7. Keep a flow of your own to monitor the round, but enjoy it as well—judging is not hard! IRREGULARITIES Occasionally, a breach in parliamentary procedure occurs, and it is the responsibility of the judge to determine the outcome. This difficulty must be resolved by a quick, but decisive, decision by the Speaker. Irregularities are either complaints made by the Opposition in the first three minutes of the Leader’s speech, or they are Points of Order and Points of Personal Privilege which can be raised at any time, but are generally associated with the rebuttals. OPPOSITION COMPLAINTS 1. Link: If the Government presents a case which is either vaguely related to or counters the resolution, the Leader of the Opposition can object. It is then left to the discretion of the judge to decide if the link is valid. Link arguments may count against the Government, but they should not be the basis of your final decision. 2. Specific Knowledge: The case must be comprised of reasonable general knowledge that most highly educated college students should be aware of. Therefore, use of evidence cards is not allowed. A specific case may be run if the knowledge is summarized or if it is related to a more general, philosophical value which may be argued outside of the example. However, no extraneous facts may be introduced by the government, such as wildly unfamiliar dates, very obscure court cases, etc. which leave the Opposition at a disadvantage. The Opposition may use as many specifics as they choose, within the same guidelines. 3. Tautology: Circular reasoning or defining the resolution in such a way that the case proves itself. For example, “Coke is it: coke is a type of soda. It is a soft drink. Therefore Coke is it.” 4. Truism: An argument which either states the status quo or is such that no one can reasonable oppose. Example: “Racism is bad” The Opposition generally deals with the latter two examples by providing a counter case. POINTS IN A DEBATE Points of Order: Breaches in parliamentary proceedings are termed points of order. They may be raised when: A. A new argument is introduced in a rebuttal. Although new examples are permissible, a new point is not. A member of the other team must rise AT THE TIME THE POINT IS BEING MADE for the objection to be valid. If you as the judge feel that a new argument has been introduced, you respond “Point well taken,” and the time it took to make the point is deducted from the speech. If a new argument has not been introduced, respond “Point not well taken, no time deducted.” Points of order may count against the speaker who breached parliamentary procedure. B. The debater carries a pen to the lectern or places their hand in pockets, No one really rises on these, but they should be well taken. C. The speaker talks for much longer than the allotted time. You should be aware of the time as well as the debaters so that you may make a fair judgement. Points of Personal Privilege: A personal assault against a participant in the debate or an offensive and tasteless assertion. It is up to you to decide whether the speaker’s comments were acceptable. What to do when a speaker rises to make a point: 1. Recognize the speaker, and ask the debater speaking to yield the floor. 2. Allow the person to make the point. 3. Decide QUICKLY, and don’t allow others to argue about the point. 4. Resume the debate.