Debate Guidelines

Debate Guidelines

A debate is a formal way of testing an idea or proposition. In debate, the idea is called the resolution. In policy debate, the resolution takes the form: Resolved: That an entity should take an action . The 2002 – 2003 policy debate topic illustrates this: Resolved:

That the United States federal government should substantially increase public health services for mental health care in the United States .

One side, called the affirmative, has the duty to affirm or support the resolution. The affirmative side presents a case that proposes a plan and reasons for adopting the plan. In the affirmative speeches, debaters typically show a need for the plan, describe the plan, and demonstrate the advantages of the plan. Debaters often craft their speeches with an eye toward judging criteria, of which there are many. One judging system uses what are called stock issues. The stock issues are:

1.

Topicality – Does the case reasonably adhere to the topic as delimited by the resolution?

2.

Significance – Is there a significant problem that justifies changing the present system?

3.

Inherency – Is there an inherent barrier in the current system that keeps it from solving the problem indicated in the affirmative case? Alternatively stated, is the current system inherently flawed or does it just need repair?

4.

Solvency – Would the proposed plan solve the problem better than the present system?

5.

Advantages – Do the advantages of the proposal outweigh the disadvantages of the proposal?

To win in this judging system, the affirmative case must receive a yes answer to every one of those questions. The negative side wins if the judge answers any question with no .

There are other judging systems, but the stock issues provide a good structure for conceptualizing the affirmative case.

The other side, called the negative, because its job is to negate the plan offered by the affirmative side, presents a case that either upholds the status quo, i.e. shows that the affirmative side’s plan should not be supported, or that another plan is superior to the one proposed by the affirmative side. Note that the negative side does not have to negate the resolution. It simply has to negate the plan offered by the affirmative side. An illustration will clarify.

Let’s say that the affirmative side proposes a plan that the federal government should improve mental health by ending compulsory education because doing so would make kids happy, and being happy is essential to good mental health. The negative side could easily show the weaknesses in that plan without rejecting the resolution itself.

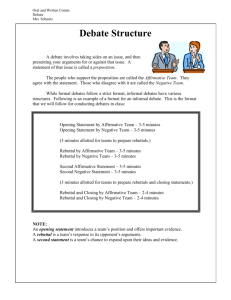

Because the affirmative side has the responsibility of supporting the resolution, the affirmative side goes first and last. Following is a list of the order of speeches for our inclass debates:

Affirmative Constructive

Cross Examination

Negative Constructive

Cross Examination

1st Affirmative Rebuttal

Negative Rebuttal

- 6 minutes – Speaker A

- 3 minutes – Speaker B questions speaker A

- 7 minutes

– Speaker B

- 3 minutes

– Speaker A questions speaker B

- 4 minutes – Speaker A

- 6 minutes – Speaker B

- 3 minutes

– Speaker A

2nd Affirmative Rebuttal

Speaker A has the following responsibilities: introduce the resolution, describe the problem, define terms in the resolution, demonstrate a need for a plan, and present the plan.

Speaker B has the responsibility of negating the plan proposed by Speaker A. There are many ways to do this. Some common techniques used by the negative speaker include: proposing another definition of the problem, offering alternative definitions of terms, denying the need for the plan, pointing out the inability of the plan to meet the need, denying the need for any plan by defending the status quo, and offering a counterplan.

Speaker B may also ask for clarification and specification of the plan.

In the second affirmative speech, Speaker A has two major tasks: review the cases presented by each side while pointing out the major areas of conflict (called clash in debate jargon), and respond to the attacks made by Speaker B. Additionally, speaker A must demonstrate that the plan proposed in the first speech will solve the problem and that the plan will do so without causing more problems than it solves.

In the second negative speech, Speaker B reviews the areas of conflict and restates the negative position. Speaker B goes on to attack the plan. There are many strategies.

Common strategies include denying that the plan solves the problem, denying that the plan is workable, or asserting that the plan would cause more problems than it would solve.

In the third affirmative speech, Speaker A responds to the negative rebuttal, summarizes the issues, and makes a final defense of the plan.

Cross examination provides an opportunity to clarify any points just raised, however the skillful debater also uses cross examination to advance his or her side of the debate. This is accomplished by asking questions for which the other side has no adequate answer, that reveal weaknesses in the affirmative case, or the answers to which can later be used by the cross examiner to bolster his or her side of the argument. The questioner should be cautious in asking questions, however, because the answers may serve to bolster the opponents’ case. Generally, a questioner should ask a question only if he anticipates that the answer will support his side of the debate.

Rebuttal speeches provide the opportunity to defend the position each side has laid out.

No new arguments may be introduced in rebuttal speeches.

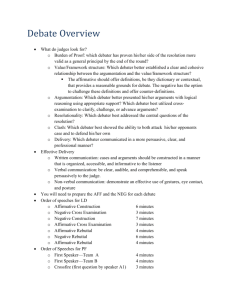

As mentioned previously, there are many criteria by which one may judge a debate. In addition to the stock issues system mentioned above, another is the policy maker system.

This system is built on the idea that judges should decide debates much as legislators would, i.e. the affirmative side wins if the plan is topical and its advantages outweigh the disadvantages presented by the negative. Another system awards the win to the side that scores the most points according to a predetermined list of criteria.

In addition to the many systems judges may use to select a winner, there are theories that influence judging. One theory holds that the judge should be a blank slate (tabula rasa) and should judge only according to what each side says in the debate. Another theory holds that the judge is a critic, that he or she critically evaluates the quality of the arguments each side makes, and makes a decision based on the quality of those arguments. It becomes apparent that judging the winner of a debate can be a challenge.

For the purposes of this class, we will not be selecting a winner, however students are well advised to consider the quality of their arguments.

Sources:

Eisenberg, A.M, & Ilardo, J.A. (1980). Argument: A guide to formal and informal debate (2 nd

ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Freeley, A.J. (1966). Argumentation and debate: Rational decision making (2 nd

ed.).

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Kruger, A.N. (1960). Modern debate: Its logic and strategy . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Musgrave, G.M. (1957). Competitive debate: Rules and procedures (3 rd ed.). New York:

Wilson.

Thomas, D.A., & Hart, J. (1987). Advanced debate: Readings in theory practice and teaching (2 nd

ed.). Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook.