Attachment 1 to OP 1749/04

advertisement

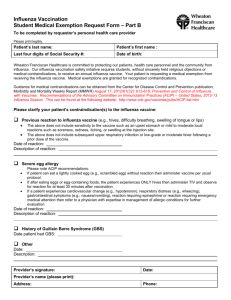

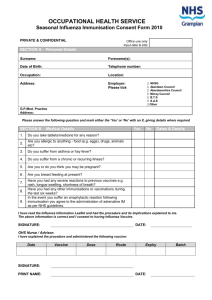

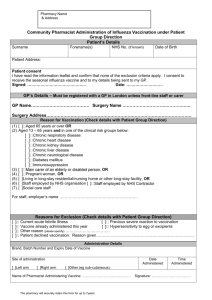

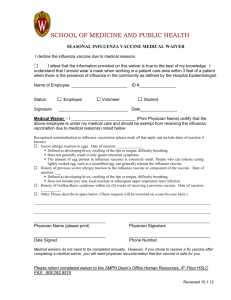

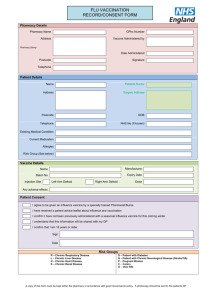

APPENDIX 1 Influenza and Influenza Vaccination Influenza is a highly contagious respiratory viral illness spread mainly by coughing and sneezing. The incubation period is about 1 to 4 days. Typical influenza is characterised by the sudden onset of fever, myalgia, headache, severe malaise, non-productive cough, sore throat, and rhinitis. Fever, cough, and fatigue are more specific indicators of influenza than other respiratory viral illnesses. People are infectious from about 1 day before to 5 days after the onset of symptoms. Typical influenza resolves after several days, although cough and malaise can persist for 2 weeks or more. Influenza can exacerbate underlying medical conditions (e.g. lung or heart disease) or lead to secondary bacterial pneumonia or primary influenza viral pneumonia. Influenza has also been associated with encephalopathy, transverse myelitis, Reye syndrome, myositis, myocarditis, and pericarditis. An estimated 100 to 300 West Australians die from influenza each year. Infection rates are highest in children, but rates of serious illness and death are highest in people 65 years of age or older and people of any age with high-risk medical conditions. Hospitalisation rates in children less than 1 year of age are similar to rates in people 65 years of age or older. Influenza vaccination is the best way to prevent influenza and its complications and is recommended for people 65 years of age or older, people of any age with high-risk medical conditions, and health care workers and household members who have frequent contact with these high-risk groups. Influenza vaccination has been associated with reductions in: hospitalisation and death in high-risk groups, respiratory illness and medical consultations in all age groups, work absenteeism in adults. In WA, about 80% of people 65 years of age or older had an influenza vaccination in 2003. Influenza vaccine usually contains two type A strains and one type B strain, representing the influenza viruses most likely to circulate each winter. The vaccine is made from highly purified, inactivated influenza viruses grown in embryonated hens’ eggs and may contain trace amounts of egg protein, preservatives, stabilisers, or antibiotics. Product information leaflets should be consulted for each vaccine to determine its exact composition. The influenza vaccine for the 2004 Australian season includes A/Fujian/411/2002 (H3N2)-like, A/New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1)-like, and B/Hong Kong/330/01-like strains. When the vaccine and circulating viruses are antigenically similar, influenza vaccine prevents influenza illness in approximately 70% to 90% of healthy adults less than 65 years of age. Vaccination of healthy adults has also resulted in decreased work absenteeism and decreased use of health-care resources, including the use of antibiotics. Among elderly persons living outside of nursing homes or similar chronic-care facilities, influenza vaccine is 30% to 70% effective in preventing hospitalisation for pneumonia and influenza. Among elderly persons residing in nursing homes the Attachment 1 to OP 1749/04 1 vaccine can be 30% to 40% effective in preventing illness, 50% to 60% effective in preventing hospitalisation or pneumonia and 80% effective in preventing death. Vaccination of health care workers has been associated with a decrease in deaths among nursing home residents. Women in their third trimester of pregnancy have a hospitalisation rate similar to non-pregnant women with high-risk medical conditions. Thus, 1-2 hospitalisations may be prevented for every 1,000 pregnant women vaccinated. Women who will be >14 weeks gestation during the influenza season should be vaccinated. Pregnant women with other high-risk medical conditions should be vaccinated before the influenza season, regardless of the stage of pregnancy. Although influenza vaccination of pregnant women has not been associated with adverse foetal effects, some experts prefer to vaccinate during the second trimester to avoid a coincidental association with spontaneous abortion, which is common in the first trimester. Reference Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza:recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2001;50 (No. RR-4). Patient Influenza & Pneumococcal Vaccination Programs Yearly influenza vaccination and five-yearly pneumococcal vaccination is recommended by the National Health and Medical Research Council for non-indigenous people 65 years of age or older, indigenous people 50 years of age or older, and indigenous people 15 to 49 years of age with a high-risk medical condition. The Australian Government funds free influenza vaccine for these high-risk groups and free pneumococcal vaccine only for the indigenous high-risk groups. A number of strategies can be adopted within hospitals to ensure that as many highrisk patients as possible are vaccinated against influenza or pneumococcal disease: Patients hospitalised with influenza have a significant risk of readmission during subsequent influenza seasons. High-risk patients should be vaccinated against influenza and pneumococcal disease, as appropriate, preferably before they are discharged from hospital. If it is not feasible to vaccinate high-risk patients before they are discharged from hospital, then they should be vaccinated during Outpatient or General Practitioner discharge follow-up appointments. Vaccination recommendations should be included in the patient’s notes and discharge letters. High-risk patients should be routinely assessed in Outpatients for influenza and pneumococcal vaccination and either vaccinated on site or referred to their General Practitioner for vaccination. Hospitals that have the capacity to do so should write to the General Practitioners of previously-admitted influenza high-risk patients each year reminding them to recall the identified patients for influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, as appropriate. Attachment 1 to OP 1749/04 2 Staff Influenza Vaccination Programs Many hospitals have established staff influenza vaccination programs to reduce nosocomial infections and staff sick leave. In general, at least 60% staff influenza vaccination coverage is required to reduce nosocomial infections and staff sick leave. Hospital influenza vaccination programs are best managed by designated infection control and/or occupational health staff. These programs require consistent administrative and collegiate support to maximise vaccine coverage. The objectives of these programs include: 1. Promoting staff influenza vaccination, 2. Offering free influenza vaccination to staff, and 3. Measuring the effectiveness and costs of the program 1. Promoting staff influenza vaccination Successful staff influenza vaccination programs require routine promotion activities including emails, letters, pamphlets, posters, vaccination stickers, broadcasts and direct support from team leaders. Some influenza vaccine companies routinely provide hospitals with staff influenza vaccination promotion materials. 2. Offering free influenza vaccination to staff The most successful staff influenza vaccination programs include the provision of free vaccine and a free, convenient, vaccination service. The most successful staff vaccination services usually utilise a mobile vaccination team visiting each ward or site, or an on-site staff vaccination clinic to maximise convenience. Some influenza vaccine companies subsidise the cost of influenza vaccine or vaccination services for staff vaccination programs. 3. Measuring the effectiveness and costs of the program Influenza vaccination programs should be evaluated each year with data including staff vaccine coverage, staff sick leave and costs, and vaccine and vaccination costs. Advice Expert advice on implementing and evaluating staff vaccination programs is available from staff immunisation coordinators of the major WA teaching hospitals or from vaccine consultants. In Western Australia, the following companies have influenza vaccine consultants: CSL Aventis Pasteur GlaxoSmithKline Attachment 1 to OP 1749/04 9328 7322 0404 467 807 0412 538 774 3 Staff Influenza Vaccination Consent Form Please read the following information about influenza vaccination and then complete and sign this form if you want to be vaccinated against influenza. CONTRAINDICATIONS TO INFLUENZA VACCINATION Inactivated influenza vaccine should not be administered to people known to have anaphylactic hypersensitivity to eggs or to other components of the influenza vaccine. Prophylactic use of antiviral agents is an option for preventing influenza among these people. However, people who have a history of anaphylactic hypersensitivity to influenza vaccine components but who are also at high risk for complications of influenza can benefit from vaccination after appropriate allergy evaluation and desensitisation. Information regarding vaccine components can be found in package inserts from each manufacturer. People with an acute febrile illness usually should not be vaccinated until their symptoms have abated. However, minor illnesses with or without fever do not contraindicate the use of influenza vaccine, particularly among children with mild upper respiratory tract infection or allergic rhinitis. SIDE EFFECTS AND ADVERSE REACTIONS Local Reactions The most frequent side effect of vaccination is soreness at the vaccination site (affecting 10% to 64% of patients) that lasts less than 2 days. These local reactions generally are mild and rarely interfere with the person’s usual daily activities. Systemic Reactions Fever, malaise, myalgia, and other systemic symptoms can occur following vaccination and most often affect people who have had no prior exposure to the influenza virus antigens in the vaccine (e.g. young children). These reactions begin 6 to 12 hours after vaccination and can persist for 1 to 2 days. Recent placebo-controlled trials demonstrate that among elderly people and healthy young adults, administration of split-virus influenza vaccine is not associated with higher rates of systemic symptoms (e.g. fever, malaise, myalgia, and headache) than with placebo injections. Immediate - presumably allergic - reactions (e.g., hives, angioedema, allergic asthma, and systemic anaphylaxis) rarely occur after influenza vaccination. These reactions probably result from hypersensitivity to some vaccine component, most likely residual egg protein. People who have developed hives, have had swelling of the lips or tongue, or have experienced acute respiratory distress or collapse after eating eggs should consult a physician for appropriate evaluation to help determine if vaccine should be administered. People who have documented immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated hypersensitivity to eggs — including those who have had occupational asthma or other allergic responses to egg protein — might also be at increased risk for allergic reactions to influenza vaccine, and consultation with a physician should be considered. Attachment 1 to OP 1749/04 4 Hypersensitivity reactions to any vaccine component can occur. Although exposure to vaccines containing thiomersal can lead to induction of hypersensitivity, most patients do not develop reactions to thiomersal when it is administered as a component of vaccines, even when patch or intradermal tests for thiomersal indicate hypersensitivity. When reported, hypersensitivity to thiomersal usually has consisted of local, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Guillain-Barré Syndrome The 1976 swine influenza vaccine was associated with an increased frequency of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). Among people who received the swine influenza vaccine in 1976, the rate of GBS that exceeded the background rate was less than 10 cases per 1,000,000 people vaccinated. Evidence for a causal relationship of GBS with subsequent vaccines prepared from other influenza viruses is unclear. Obtaining strong epidemiologic evidence for a possible small increase in risk is difficult for such a rare condition as GBS, which has an annual incidence of 10 to 20 cases per 1,000,000 adults, and stretches the limits of epidemiologic investigation. More definitive data probably will require the use of other methodologies (e.g., laboratory studies of the patho-physiology of GBS). During three of four influenza seasons studied during 1977 to 1991, the overall relative risk estimates for GBS after influenza vaccination were slightly elevated but were not statistically significant in any of these studies. However, in a study of the 1992 to 1993 and 1993 to 1994 seasons, the overall relative risk for GBS was 1.7 (95% confidence interval = 1.0–2.8; p = 0.04) during the 6 weeks after vaccination, representing approximately 1 additional case of GBS per 1,000,000 people vaccinated. The combined number of GBS cases peaked 2 weeks after vaccination. Thus, investigations to date indicate no substantial increase in GBS associated with influenza vaccines (other than the swine influenza vaccine in 1976) and that, if influenza vaccine does pose a risk, it is probably slightly more than one additional case per million people vaccinated. Cases of GBS after influenza infection have been reported, but no epidemiologic studies have documented such an association. Substantial evidence exists that several infectious illnesses, most notably Campylobacter jejuni and upper-respiratory tract infections in general, are associated with GBS. Even if GBS were a true side effect of vaccination in the years after 1976, the estimated risk for GBS of approximately 1 additional case per 1,000,000 people vaccinated is substantially less than the risk for severe influenza, which could be prevented by vaccination among all age groups, especially people aged >65 years and those who have medical indications for influenza vaccination. The potential benefits of influenza vaccination in preventing serious illness, hospitalisation, and death greatly outweigh the possible risks for developing vaccineassociated GBS. The average case-fatality ratio for GBS is 6% and increases with age. No evidence indicates that the case-fatality ratio for GBS differs among vaccinated people and those not vaccinated. The incidence of GBS among the general population is low, but people with a history of GBS have a substantially greater likelihood of subsequently developing GBS than people without such a history. Thus, the likelihood of coincidentally developing GBS after influenza vaccination is expected to be greater among people with a history of GBS than among people with no history of this syndrome. Whether influenza vaccination specifically might increase the risk for recurrence of GBS is not known; Attachment 1 to OP 1749/04 5 therefore, avoiding vaccinating people who are not at high risk for severe influenza complications and who are known to have developed GBS within 6 weeks after a previous influenza vaccination is prudent. As an alternative, physicians might consider the use of influenza antiviral chemoprophylaxis for these people. Although data are limited, for most people who have a history of GBS and who are at high risk for severe complications from influenza, the established benefits of influenza vaccination justify yearly vaccination. Source Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of influenza:recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2001;50 (No. RR-4). Attachment 1 to OP 1749/04 6