Tax-Exempt Organizations - Office of General Counsel

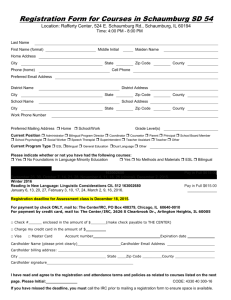

advertisement