III. Eliminating transmission line mismatch

Chapter 2

Part 1: Transmission Lines Basics

Definition: A transmission line is a mechanical structure that guides EM energy in a desired direction.

Basic properties of transmission lines:

TEM mode transmission lines: E and H are in the transverse plane, a plane that is perpendicular to the direction of the EM wave propagation.

Commonly used lines consisting a pair of parallel conductors usually belong to this class.

Higher-order transmission lines: One of the field components is in the direction of the EM wave propagation. Waveguide types consisting a hollow conductor usually belong to this class (next semester).

Dispersion in most commonly used transmission lines such as coaxial lines is negligible. However, the line loss is usually high especially at microwave frequencies.

On the other hand, waveguides suffer much lower losses at microwave frequencies but dispersion can be a problem.

The most popular TEM lines are (Fig. 2-4, P. 38):

Coaxial cable: Used mainly in the high-frequency regime (MHz and up) at

low- to medium -power levels.

Parallel-wire: Used mainly for lower frequency transmission (AC power line) at high-power levels.

Microstrip: Used mainly for microwave IC and PC board fabrications.

The most popular higher order transmission lines are (Fig. 2-4, P. 38):

Waveguide: Hollow conductors used at high frequencies and high-power.

Optical fiber: Concentric dielectric layers used at optical frequencies.

Differences and similarities between a transmission line and a waveguide:

They both are mechanical structure used to carry EM energy.

Transmission line has two parallel conductors; waveguide has only one, usually hollow, conductor.

Waves inside transmission line are TEM; waveguide waves are TE or TM.

Transmission line has higher loss, especially at high frequencies.

Waveguide waves may be distorted due to dispersion.

Transmission line has no low-frequency limit; waveguide acts like a highpass filter.

In general, the impact on the signal integrity is much severe from the effect of distortion than from the effect of losses.

Beside guiding EM energy, short sections of transmission line can sometimes be used as high-frequency discrete circuit components such as Z transformer, filter, …

Simplifications (Fig. 2-1, P. 35):

Source: A voltage source and a series resistor are used to represent the generator (Thevenin’s theorem)

Load: A resistance (impedance) is used to represent the load.

Transmission line: A two-port network is used to describe a general transmission line.

The effect of short

(transmission line effect):

Guideline: l > 0.01

(1% of the wavelength)

Phase shift: The voltage and current along a transmission line generally vary as a function of position.

Short

Long

Reflection: If the line is not terminated properly (with a match load) portion of the energy will be reflected back to the generator. This is usually bad because:

1) Reflected energy is wasted

2) Generator may be damaged if the reflection is significant.

Power loss: Energy is dissipated due to conduction loss and dielectric loss.

Distortion: A signal containing more than one frequency component may be distorted due to dispersion—different frequency components traveling at different speeds in a waveguide.

Lumped-element model

We will first consider the general properties of a TEM mode line.

Similar to your calculus classes, we are going to cut a thin slice

(differential section) of the line and examine its electrical properties.

Transmission line parameters (Formula table—P. 41):

Series L

’ and

R

’ per unit length

Parallel C

’ and

G

’ per unit length

Transmission line equations (Telegrapher’s equations): We can derive a set of circuit equations for a differential slice of the above model and from them a set differential equations can be developed to describe the voltage and current in a transmission line.

~

V

(

~

V

d V

~

)

I

~

( R '

j

L ' ) dz

d V

~

( R '

j

L ' ) I

~ dz

I

~

( I

~

d I

~

)

(

~

V

~ d V )( G '

j

C ' ) dz

d I

~

( G '

j

C ' )

~

V dz

Wave equations: Combining the two 1 st

order/2-unknown equations we have a pair of

2 nd d

2

~

V

~

V dz

2

order/1-unknown equations.

V

0

e

2

~

V z

0

V

0

e d

dz z

2

2

I

~

I

~

2 I

~

I

0

e

0 z

I

0

e

z

j

( R '

j

L ' )( G '

j

C ' )

V

I

0

0

V

0

I

0

Z

0

R '

G '

j

j

L '

C ' u p

f

– propagation constant

– attenuation constant = Re{

},

– phase constant = Im{

}, u p

– phase velocity, Z

0

– characteristic impedance = v/i for a single wave

The time domain solution to the voltage wave equation due to sinusoidal excitation is: v ( z , t )

V

e

Travels z cos(

in the t

z

z

direction

)

V

e

Travels z cos(

in the t

z

z

direction

)

Electrical length:

The electrical length of a line is the ratio of the physical length to the wavelength of the line signal. As a result, a physically long line may have a short electrical length if a low-frequency signal (long

) is being transmitted and vice versa.

Electrically short lines: For example, AC power lines less than 50 miles long are usually considered electrically short. For such cables we can consider them as discrete passive components.

R + j X

Medium-length lines: In general, power lines between 50 miles and 150 miles long are considered to be medium-length lines. We can also consider them as discrete passive components with a more complex structure.

Z /2

Y

Z /2

Short and medium lines are important in low-frequency applications such

as power transmission. They are handled with lumped-circuit theory.

Electrically long lines: A line is considered to be electrically long if its physical length is comparable to the wavelength. For example, a 15 cm coaxial cable would be considered electrically long at 3 GHz (

= c / f =

3E8 / 3E9 = 0.1 m = 10 cm).

Because at high frequencies the physical length of an electrically long line is often very short, the series resistance becomes negligible.

Since low-loss materials are usually required to fabricate high-frequency cables, the shunt conductance can also be neglected.

Lossless (ideal) line ( R

’ =

G

’ = 0

= 0): d

2

~

V

2

~

V

~

V dz

2

V

0

e

j

z

V

0

I

0

V

0

I

0

Z

0

0 d

2 dz

2

V

0

e

j

z

I

~

2

I

~

I

~

0

I

0

e

j

z

L ' C '

I

0

e

j

z

L '

C ' u p

f

For all TEM lines:

L ' C '

and

G '

C '

and u p

1

c

r

0

r where

0

f c

(free space wavelengt h)

Dispersion refers to the spreading of a signal due to the differences in speed between different frequency components. It is often detrimental to

digital communication since digital pulses contain multiple frequency components.

Since the phase velocity is independent of frequency, ideal TEM lines are nondispersive.

Terminating an ideal line

The characteristic impedance Z

0

of a transmission line is not a real resistance even though it has a unit of ohm. Z

0

of a line merely represents the ratio of the voltage and current of one traveling wave along the line. If more than one wave (for example, incident and reflected waves) are present in the line, the ratio of the total voltage and total current would not equal to Z

0

.

I

-

,V

-

I

+

,V

+ z

Z

0 l

Z

L

0

V

L

V

0

V

Z

L

L

V

0

V

0

Z

0

I

L

V

0

Z

0

I

0

I

0

V

0

Z

L

V

0

V

0

Z

0

V

0

e j

r

V

0

V

0

I

I

0

0

Z

L

Z

L

Z

0

Z

0

Z

L

1

Z

0

Z

L

1

Z

0

If a transmission line is terminated with a load resistance Z

L

equal to its characteristic impedance Z

0

there will be no energy reflected from the load. In other words, a matched load acts like an infinitely long line with the same Z

0

.

For a mismatch load, part of the energy will be reflected back to the generator. The amplitude of the reflected wave is according to the above formula.

The portion of power reflected back is

2

.

= 1 for o/c and

= -1 for s/c

|

| = 1 for purely reactive loads.

1.

Examples (P. 50-51)

More examples: Z

0

= 50

Z

L

= 55

= ( Z

L

– Z

0

) / ( Z

L

+ Z

0

) = (55 – 50) / (55 + 50) = 5/105 = 0.048

2

= 0.0482 =0.0023 = 0.23%

2.

Z

L

= 45

= ( Z

L

– Z

0

) / ( Z

L

+ Z

0

) = (45 – 50) / (45 + 50) = -5/95 = -0.053

2 = 0.0532 =0.0028 = 0.28%

3.

Z

L

= 5

= ( Z

L

– Z

0

) / ( Z

L

+ Z

0

) = (5 – 50) / (5 + 50) = -45/55 = -0.82

2 = 0.822 =0.67 = 67%

4.

Z

L

= 5 K

= ( Z

L

– Z

0

) / ( Z

L

+ Z

0

) = (5000 – 50) / (5000 + 50) =

4950/5050 = 0.98

2 = 0.982 =0.96 = 96%

5.

Z

L

= 75 + j25

Z

0

50

Z

L

Z

0

Z

L

Z

0

Z

L

75

25j

Z

L

Z

0

25

25i

Z

L

Z

0

125

25i

Z

L

L

Z

0

Z

0

35.355

45 deg

Z

L

L

Z

0

127.475

Z

0

11.31 deg

35.355

0.277

0.231

0.154i

45

11.31

33.69

127.475

arg

33.69 deg

0.277

2

7.692 %

Impedance transformation:

The input impedance is the ratio of the total line voltage to the total line

current. This ratio in general varies along the line and thus the input impedance is a function of the distance between the measurement point and the load.

For an ideal line (lossless) terminated with a match load the input impedance Z in

measured at any distance always equals to Z

0

.

On the other hand, if Z

L

Z

0

then Z in

will vary as a function of the distance away from the load.

Z in

Z

0 l

Z

L

The input impedance Z in

:

Z in

( z )

V

I

~

(

~

( z z

)

)

V

0

V

0

e e

j

j

z z

V

0

V

0

e

e

j

z j

z

Z

0

Let z

l

Z

0

e

e

j

z j

z

e

j

z

e

j

z

Z in

(

l )

Z

0

e e j

l j

l

e

j

l

e

j

l

Z

0

1

1

e

2

e

2 j

l j

l

The input impedance Z in

measured at any distance l from the load is:

Z in

(

l )

Z

0

Z

Z

L

0 cos cos

l l

jZ jZ

0

L sin sin

l l

Z

0

Z

Z

L

0

jZ jZ

0

L tan tan

l l

As a result, the input impedance of an unmatched line can vary drastically

as a function of l .

l

0

l

90

180

270

360

0

/4

/2

3

/4

Examples: Z

0

= 50

, f = 3 GHz

1) Z

L

= 0

and

= 3E8 / 3E9 = 10 cm Z in

Z in

= 0 for

l = 0

, 180

, 360

, …

= jZ

0

(sin

l / cos

l )

Z in

=

for

l = 90

, 270

, …

A shorted line 2.5 cm long sometimes looks like an open.

2) Z

L

=

and

= 3E8 / 3E9 = 10 cm Z

Z in

=

for

l = 0

, 180

, 360

, … in

= jZ

0

(cos

l / sin

l )

Z in

= 0 for

l = 90

, 270

, …

Z

0

l

l

Z in

50

360deg

Z

0

Z

L

Z

0

Z

L

3)

An open line 2.5 cm long sometimes looks like a short.

For Z

L

= 30

and v = 0.8 c, find Z in

for a 5.5 cm line

0.8 3

10

8 m

30 f

9

Hz l

2 m

f s

l

0.687

0.08 m cos cos

l

247.5 deg

j Z j Z

0

L

sin sin

Z

L

Z

L

cos

cos

11.481

j Z

0

sin

j Z

0

sin

11.481

46.194i

46.194i

Z

0

cos

Z

0

cos

19.134

j Z

L

sin

j Z

L

sin

27.716i

19.134

27.716i

11.481

46.194i

47.599

19.134

27.716i

33.679

arg (

11.481

Z

L

cos

Z

0

cos

L

2

f

24.935

46.194i

)

103.957

j Z

0

sin

deg

1.413

arg

j Z

L

sin

L

1.323

10

Z

L

cos

Z

0

cos

9

H Z in

arg (

19.134

j Z

0

sin

j Z

L

sin

70.665

27.716i

)

124.62

deg

20.663 deg

Z in

66.119

24.935i

20.663 deg

Z

0

50

4) For Z

L

= 30

and v = 0.8 c, find Z in

for a 2.2 cm line

Z

L

30 l

2

0.8 3

10

8

9

0.08

l

Z in

l

360deg

Z

0

Z

L

cos

Z

0

cos

l

99 deg j Z

0

sin

j Z

L

sin

Z

L

cos

4.693

j Z

0

sin

49.384i

Z

L

cos

j Z

0

sin

4.693

49.384i

11.481

46.194i

47.599

Z

0

cos

7.822

j Z

L

sin

29.631i

Z

0

cos

j Z

L

sin

7.822

29.631i

19.134

27.716i

33.679

arg (

11.481

46.194i

)

103.957

deg arg (

19.134

27.716i

)

124.62

deg

Z

L

cos

Z

0

cos

j Z

0

sin

j Z

L

sin

1.619

arg

Z

L

cos

Z

0

cos

j Z

0

sin

j Z

L

sin

9.359

deg

Z in

79.859

13.161i

Z in

80.936

9.359

deg

C

2

3

10

9

13.161

1

C

4.031

10

12

From the examples we conclude that a short section of transmission line can transform a short to an open and vice versa. It can also transform a

capacitance to an inductance and vice versa.

Properly terminating the output of microwave amplifiers and oscillators is important.

Tune circuits at microwave frequencies usually require L and C with extremely small values. Using small segments of transmission line is one way to accomplish this requirement.

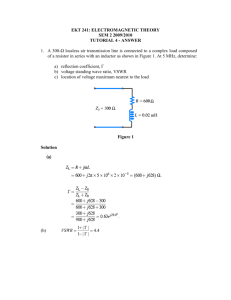

Complete solution of the wave equations (Example 2-5, P. 57-58):

V

0

g

Z

V

~ g g

Z

in

Z in

e j

l

1

e

j

l

Standing waves:

Transmission line waves (incident and reflected) are traveling waves in

opposite directions. It is usually difficult to observe them separately.

The combined wave displays an alternating pattern (repeats at every ½

) of constructive and destructive interference between the incident and

reflective waves.

The envelop of this pattern is called the standing wave.

The best way to visualize the standing wave pattern is to visit the following web site: http://graphics.cs.ucdavis.edu/~schussma/xl.html

In this transmission line simulation you can specify the magnitude and phase of the reflection coefficient. The program will then display the incident, reflective, and total wave along the line as well as the envelop of the total wave (standing wave pattern).

!!! Everybody should try this !!!

Match load: Since no reflection exists in the line, no standing wave pattern is observed (0 V swing between maximum and minimum).

Open-circuit (o/c) load: Since V + and V are the same at Z

L

, we expect the load voltage to be doubled at Z

L

and complete cancellation at ¼

away (2

V swing). This pattern repeats every ½

.

Short-circuited (s/c) load: Since V

+

and V

V swing). This pattern repeats every ½

.

-

are opposite at Z

L

, we expect complete cancellation at Z

L

and the voltage to be doubled at ¼

away (2

Larger load-100

: Similar to o/c with less voltage swing between maximum (0.667V) and minimum (0.333 V).

Smaller load-25

: Similar to s/c with less voltage swing between maximum (0.667V) and minimum (0.333 V).

In summary, voltage maxima are located at n

½

(1/2

, 1

, 1 1/2

,

…) for resistive loads larger than Z

0

and at ¼

+ n

½

(1/4

, 3/4

, 1

1/4

, …) for resistive loads smaller than Z

0

.

Minima are located at ¼

away from maxima.

The locations on the line corresponding to voltage maxima also correspond to current minima, and vice versa.

In general, voltage maxima occur at locations where the incident and reflective waves are in phase (constructive interference). For a complex load impedance, the locations of voltage maxima are given by:

~

V ( z )

V

0

( e

j

z e

j

z

)

V

0

( e

j

z e j

r e

j

z

)

z

r

z

r

2

z

0 ,

2 n

l max

r

2 n

2

4 r

n

2

n

1 , 2 , ...

if n

0 , 1 , 2 , ...

if

r

r

0

0

In general, voltage minima occur at locations where the incident and reflective waves are out of phase (destructive interference). For a complex load impedance, the locations of the first voltage maximum and minimum are given by: l max

r

4

r

4

l min

4

2

4

4

r

r

r r

2

2 r

2

l max l max

r

2

2

/ 4

/ 4 if if if if

r

r l max l max

0

0

/ 4

/ 4

If we measure the first maximum or minimum of the standing wave the phase angle of the reflective coefficient can be computed:

r

l

max l max

4

2

2

4

l max

2

2

l min

r

Summary of

r

calculations: l max

2

r if if l l max max

4 or 2

l max

4 or 2

l max

0

-

r

2

2

l min

0

2

2

l max

-

VSWR (Voltage Standing Wave Ratio): A quantity that can be measured easily. The reflective coefficient and input impedance can be computed from the VSWR and the locations of the first minimum or first maximum.

S

~

V max

~

V min

1

1

Z

L

S

1

S

Z

1

0

1

1

Example 2-5 (Slotted-line), P.54-55

Special cases:

Short-circuited line: A short-circuited line behaves like a discrete reactive component with:

SC

Z in

jZ

0 tan

l

For length between 0 and ¼

it is inductive with equivalent L:

L eq

Z

0 tan

l

l

1

tan

1

L eq

Z

0

For length between ¼

and ½

it is capacitive with equivalent C:

C eq

Z

0

1 tan

l

l

1

tan

1

C

1 eq

Z

0

The reactive type repeats beyond l > ½

following the same pattern (Fig.

2-15d, P. 59).

Open-circuited line: An open-circuited line behaves like a discrete reactive component with:

Z

OC in

jZ

0 cot

l

tan jZ

0

l

For length between 0 and ¼

it is capacitive with equivalent C:

C eq

tan

0

l

l

1

tan

1

C eq

Z

0

Z

For length between ¼

and ½

it is with inductive equivalent L:

L eq

Z tan

0

l

l

1

2

tan

1

Z

L

0 eq

The reactive type repeats beyond l > ½

following the same pattern (Fig.

2-17d, P. 61).

In microwave and high-speed circuits small C and L are often needed. It is

much easier to fabricate them using transmission lines segments.

Transmission parameters ( Z

0

and

) can be determined from the results of

OC and SC measurements (Example 2-8, P. 61).

Z

0

Z

SC in

Z

OC in

1 l tan

1

Z

Z in

SC in

OC

1/2 wave window: A 1/2

section of transmission line, regardless of characteristic impedance, can be inserted into an existing transmission line system without disturbing the electrical properties of the system.

Z in

Z

1

Z

Z

1

L cos cos

l l

jZ

1 jZ

L sin sin

l l

Z

1

Z

Z

L

1

( 1 )

( 1 )

jZ

1 jZ

L

( 0 )

( 0 )

Z

L

Z in

= Z

L

Z

0 l

Z

1

/2

Z

L

1/4 wave transformer: A 1/4

section of transmission line (Z

02

) can be inserted into used to match any Z

01

to Z

L

.

Z in

Z

02

Z

Z

L

02 cos cos

l l

jZ jZ

02

L sin sin

l l

Z

02

Z

Z

L

02

( 0 )

( 0 )

jZ

02

( 1 ) jZ

L

( 1 )

Z

02 jZ

02

( 1 ) jZ

L

( 1 )

Z

01

Z

02

Z

01

Z

L

Z in

= Z

01

Z

01

Z

02

Z

L l

/4

Example: match a 50-

line to a 200-

load at 100 MHz ( v = c/8).

/4 = (c/8) / f / 4 = 0.094 m

Z

1

= (50

200)

1/2

= 100

Summary of lossless transmission line properties (Table 2-3, P. 63):

Z in

is real at maxima and minima.

At voltage maxima: Z in

= Z

0

[(1 + |

|)/(1 – |

|)]

At voltage minima: Z in

= Z

0

[(1 – |

|)/(1 + |

|)]

Power flow in ideal lines

Instantaneous power:

P i

( t )

V

2

Z

0 cos

2

(

t

)

P r

( t )

2

V

Z

0

Average power:

2 cos

2

(

t

r

) i

P av

V

2

2 Z

0

P av r 2

V

2

2 Z

0

P av

V

2

2 Z

0

2

P av i

Chapter 2

Part 2: Smith chart

Introduction

The primary objective of the Smith chart is to graphically compute the input impedance at any position along a transmission line terminated with an arbitrarily load.

Powerful graphical tool for computing the complex impedance of transmission line circuits (Originally called transmission line calculator).

Useful CAD presentation tool for displaying the performance (noise, gain, stability, …) of microwave circuits.

Still a good way to design matching networks.

Useful for lossless or lossy lines.

Components of the chart

Polar plot for the reflection coefficient at the load (Fig. 2-20, P. 67).

Lines of a pair of parametric equations, one for the real (resistive) part and

the other for the imaginary (reactive) part, are plotted on the chart to indicate the normalized load impedance ( z

L

= Z

L

/ Z

0

) (Fig. 2-21, P. 69).

Three concentric scales are on the perimeter of the chart (Fig. 2-22, P. 70).

The innermost scale indicates the phase angle of the reflection coefficient.

The other two scales indicate the distance, in terms of electrical length (

), of the movement of the measurement plane. o The outermost scale WTG (

toward generator) indicates the movement of the measurement plane toward the generator (away from the load). o The middle scale WTL (

toward load) indicates the movement of the measurement plane toward the load (away from the generator).

Graphical calculations

The reflection coefficient

along the line: The magnitude of

is constant along the line. The only other unknown is the phase angle

r

.

1) Plot the normalized load impedance ( z

L

= Z

L

/ Z

0

) on the chart.

2) Draw a radial line through z

L

until it intersects the

r

scale.

3)

r

is at the position where the radial line intersects the

r

scale.

VSWR:

1) Plot the normalized load impedance ( z

L

= Z

L

/ Z

0

) on the chart.

2) Starting at z

L

, draw a complete circle centering at the origin. This is called the constant-|

| circle, or more commonly known as the SWR circle since S is a function of |

| only.

3) S equals to the value where the SWR circle intersects the

= 0

radial line.

The first voltage minimum equals to the angular displacement between z

L and the

= 180

radial line using the WTG scale (Fig. 2-24, P. 74).

The first voltage maximum equals to the angular displacement between z

L and the

= 0

radial line using the WTG scale. You can also use l min

¼

to obtain l max

.

The normalized input impedance ( z in

= Z in

/ Z

0

) along the line:

1) Plot the normalized load impedance ( z

L

= Z

L

/ Z

0

) on the chart.

2) Draw a radial line through z

L

until it intersects the WTG scale. This is the starting position WTG start

.

3) From the physical distance between the measurement plane and the load, compute the equivalent electrical length

(in

).

4) From the WTG scale compute the equivalent angular movement.

WTG final

= WTG start

+

5) Draw a radial line through WTG final

.

6) Starting at z

L

, draw a complete circle centering at the origin. This is called the constant-|

| circle, or more commonly known as the SWR circle since S is a function of |

| only.

7) z in

is at the position where the WTG final

radial line intersects the the

SWR circle.

Z in

is real at

= 0

and is maximum (= Z

0

S); Z in

is real at

= 180

and is minimum (= Z

0

/ S)

Z-Y conversion: It is often more convenient to work with Y since parallel

Examples 1-5

Impedance matching

components are easier to insert into a transmission line circuit (???) and the result can be obtained by simply adding the Y

’s.

In a Smith chart z (= Z / Z

0

) and y (= Y / Y

0

=

Example 2-10, P. 76-78 and 2-11, P. 78.

Y Z

0

) are 180

apart.

Whenever a transmission line is not terminated with a matched load ( Z

L

=

Z

0

, portion of the incident energy will be reflected back. This usually causes two problems: 1) energy is wasted; 2) the reflected energy could

upset/damage the transmitter.

Components are added between the generator and the load to achieve matching. This is called an impedance-matching network.

The match point in a Smith chart is at the origin where z in

= y in

= 1 + j 0

The single-stub matching technique:

1) Since the stub, which is a section of transmission line with a sliding short at the end, is connected in parallel to the line, it is more convenient to work with admittance than impedance. First transform z

L into y

L

by rotating the z

L

180

along the SWR circle.

2) Determine where to attach the stub by rotating y

L

in the CW (WTG) direction along the SWR circle until it intersects the real circle = 1. At this location the y in

has a real part = 1.

3) There will be two points on the chart that satisfy the above condition

(real{ y in

} = 1).

4) Measure the electrical length (in

) for the above rotation and convert it into physical distance d . This should be the distance between the load and the stub.

5) Determine the imaginary part (susceptance) of y in

(= j B ) from the chart.

6) Starting from the short circuit point (where and why), rotate in the CW

(WTG) direction along the SWR =

circle (outer rim) until it intersects the imaginary line = j B . At this location the y in

of the stub has a susceptance = j B .

7) Measure the electrical length (in

) for the above rotation and convert it into physical distance l . This should be the length of the stub.

Example 2-12, P. 80-84.

Example 6

Discrete conjugate matching: Handout

Chapter 2

Part 3: Transient (Pulse) Transmission Line Responses

Introduction

So far we have studied the high-frequency behavior of transmission lines

under harmonic excitations, in this part we are going to examine the pulse responses of transmission lines.

Because of reflections due to mismatch, an electrically long transmission

line may respond irregularly to pulsed signals.

Transient response of a line is a time record of the pulses bouncing between the transmitting and receiving end.

Transmission line responses

The steady-state response can be calculated using ordinary dc circuit

analysis techniques.

The transient response calculations must include the reflected waves between the generator and load.

The reflections may cause severe distortion to the wave shape of the signal.

They may even damage the receiver or transmitter because of EOS

(electric overstress) or polarity reversal.

Computing the transient response

The transient response is usually difficult to compute. To simplify the analysis, a rectangular pulse is decomposed into two step functions. The

step response is then computed and the pulse response is computed by adding the two step responses (Fig. 2-32, P. 84).

Bounce diagram (Fig. 2-35, P. 89): The bounce diagram is used to keep track of the multiple reflections along the line.

TDR: Measures the round-trip time as well as the shape of the reflected pulse to determine the distance and the type of discontinuity. Used for fault detection, location, and identification. It can also be used to measure the length of long transmission lines (Example 2-13, P. 89).

Computer simulation results:

R

G

= R

L

= 10

R

G

= R

L

= 100

R

G

= 10

R

L

= 100

R

G

= 100

R

L

= 10

Chapter 2

Appendix

I.

Transient Response

The response of a circuit can be extremely complex. To simplify the analysis we often separate the response into two parts:

Steady-state response: This response represents the behaviors of the circuit after a long period of time (until the effect of initial conditions has

diminished to a negligible level). The steady-state response can usually be computed using basic AC/DC circuit laws.

Transient response: This response represents the behaviors of the circuit

immediately after the input is applied. It is usually more difficult to solve since it involves both the input and the initial conditions.

There are other classifications of the circuit responses such as frequency response vs. time response, force response vs. natural response, and zerostate response vs. zero-input response.

Properties of transient response:

Preshoot: A change of amplitude in the opposite direction before the pulse.

Overshoot: The overshooting of the amplitude after the initial transition.

Rounding: The rounding of the amplitude after the initial transition.

Ringing: The peak-to-peak amplitude following the overshooting.

Note: The above parameters are expressed as % of the steady-state amplitude.

Period: The duration required for the waveform to repeat itself.

Pulse width: The time duration between the 50% point of the leading and trailing edges of the pulse.

Rise time: The duration between the 10 and 90% of the steady-state value.

Settling time: The duration required to reach the steady-state amplitude after the pulse has reached the 100% point.

Droop: The decrease of amplitude with time.

Nonlinearity: The deviation from the line between the 10 and 90% points.

II.

Electrical Component Parameters

Conductance ( G ) / resistance ( R ): The basic electrical property of a resistor is how well (poorly) it conducts electricity (AC and DC).

R – The resistance of a resistive component.

G – The conductance of a resistive component.

R = 1 / G

Reactance ( X ) / susceptance ( B ): The basic electrical property of a capacitor or an inductor (reactive component) is how much it shifts the phase angle of an AC signal at a particular frequency.

X – The reactance of a reactive component.

X

C

= -1/2

fC

X

L

= 2

fL

B – The susceptance of a reactive component.

B

C

= 2

fC

B

L

= -1/2

fL

X = 1 / B

Inductance ( L ) / capacitance ( C ):

L: X

L

> 0, B

L

< 0

C: X

C

< 0, B

C

> 0

Impedance ( Z ) / admittance ( Y ): The combined property of a component or circuit with both resistance and reactance.

Z = R + jX

Y

Z

Z – Y Conversion:

Z

Z

=

=

to

G

1 / Y

Y

R

+

:

jB jX

Y

1

Z

G

Y

Y cos

Y

G

jB

Y to Z :

Y

G

jB

1

R

2

X

2

Y

Z

B

Y

tan

1

sin

Y

X

R

tan

1

X

R

if R

0 if R

0

Z

1

Y

R

Z

Z cos

Z

R

jX

1

G

2

B

2

Z

X

Y

Z

tan

1

sin

Z

tan

B

G

1

B

G

if G

0 if G

0

III.

Eliminating transmission line mismatch

Reference: David Royle; Designer’s Guide to Transmission Lines and

Interconnections; EDN, June 1988.

Criteria:

Time domain: The time required to travel the length of the interconnection is greater than the 1/8th of the signal rise time.

Note: Rise time refers to the rise or fall time, whichever is smaller, and it corresponds to the

0% to 100% time duration. To convert from the 10% – 90% rise time to the 00% – 100% rise time multiply by 1.25.

Frequency: The length of the interconnection is greater than 1/15th of the wavelength of the highest frequency component of the signal.

Remedies: