Logic can be described as a way of thinking about

advertisement

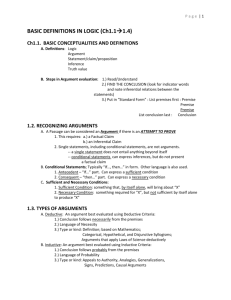

I-reading: Arguments: Induction vs. Deduction (Guttenplan, 1-10) You probably found that finding arguments and putting them into standard form is much easier than paraphrasing the structure of passages in the earlier sections. Now comes the hard part: discriminating the different kinds of arguments and evaluating them. We will begin the work of distinguishing the two main types of arguments in this section and will discuss how to evaluate them in subsequent sections. The main division in arguments is between formal (deductive) and informal (inductive) inference styles. This means that there are different ways that premises support a conclusion. And, yes, unfortunately, “styles” is the appropriate term. The difference between a deductive and inductive argument will not be apparent in their content, so do not think that deductive arguments are more factual than inductive ones. In fact, the very same content can often be treated as deductive or inductive with only slight differences in presentation. Explaining this will be much easier if we can look at some examples: Example 1: Inez finds that her car won't start. She remembers that when Jones's car failed to start, it was because the distributor was wet. She also recalls reading that distributor problems are common in the sort of car she has. She is aware of how damp it is today. She concludes, therefore, that a wet distributor is the cause of the trouble. Example 2: Dennis is planning his summer holiday. He knows that he can go by airplane or car. If he goes by airplane, he will get there faster, but will be unable to take much luggage. If he goes by car, he can take much more. He recognizes that the success of his holiday depends on his having the right sort of clothing for the unpredictable weather. He could not take the needed clothing on the airplane. He concludes that if the holiday is to be successful, he will have to go by car. The First Example: Inez’s Thoughts 1. My car doesn't start. 2. When Jones's car didn't start, the trouble was a wet distributor. 3. Cars like mine have this as a common problem. 4. It is very damp today. -------------------------------------------------------------------------Therefore, she concludes, the cause of my car trouble is a wet distributor. The Second Example: Dennis’ Thoughts Here is the standard form argument of Dennis' thoughts: 1. I can go on holiday by airplane or car. 2. If I go on holiday by airplane, then I shall get there faster, but cannot take much luggage. 3. If I go by car, I can take more luggage. 1 4. A successful holiday requires that I take the right clothing. 5. I couldn't take the right clothing on the airplane. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Therefore, he concludes, if my holiday is to be a success, I must go by car. The transition from the premises to the conclusion is what I want you to focus on. A first thing one might say is this: Inez’s conclusion followed from her premises in a way that made sense, but Dennis’ conclusion followed with more precision. We want to say that there is a logical relation between Dennis’ premises and his conclusion, whereas the relation between Inez’s premises and conclusion is closer to what one would call smart or reasonable as opposed to precise. Inez made a wise summation from her thoughts, but Dennis’ conclusion was produced by his prior thoughts. A Third Type of Argument Let’s look at Jeff’s nightly thought process: Example #3: There are leftovers in the frig. I forgot to eat lunch again. I really shouldn’t eat a lot right before bed. Aw, heck, who am I kidding, I can’t control myself, hand me an extra large fork... It is clear that the movement of thought in Jeff’s case is different from that in Inez’s case and radically different from that in Dennis’ case. There are many times when our thoughts move from one to another in a connected way, but we often see no need to justify our reasoning because it seems so obviously logical. It cannot be said that Jeff’s reasoning was logical, that is, we would not say that his conclusion was produced by his prior thoughts. This difference between Jeff’s argument and the other two is simply a matter of Jeff’s being illogical and the others being logical. Both Inez's and Dennis' thoughts involved transitions which could be defended. Yet there is a very important difference between these two cases: Dennis’ argument is easier to justify than Inez’s, that is, the movement from Dennis’ assumptions to his conclusion is more certain than Inez’s. This is the key distinction between deductive, or formal, arguments and inductive, or informal, ones: in a deductive argument the goal is to produce an argument in which it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false. In other words, the truth of the premises would guarantee the truth of the conclusion because the logical movement between them is so precise. Inez employed her thinking to discover why her car didn't start. At the end of her thought episode, she held the view that a wet distributor was the fault. Moreover, she came to this view by a route that she would defend as justified. What would you say of all this if it turned out that the fault in the car was not a wet distributor? Would Inez be forced to admit that some item in her inventory was false? The answer to this last question is surely “No”. Does this mean that there was something wrong with the way in which she arrived at her final thought? The answer here is again “No”. Inez's method of getting to her conclusion was perfectly reasonable, given what she believed in the first place. It is simply a feature of this sort of movement of thought that, on the one hand, we think it justifiable or reasonable, and, on the other hand, we are prepared to admit that the truth of the initial thoughts does not guarantee the truth of the concluding thought. In short, there can be movements of thought which are defensible but which do not lead to their conclusion with necessity. 2 This is in contrast to the case of Dennis. Suppose it turned out that Dennis took the airplane, and had a successful holiday. Here we would say that he must have been mistaken about one of the thoughts in his assumptions. If they were all true, then this would have guaranteed the truth of his final thought. Both sorts of thinking are defensible, but Dennis can offer a special ground for his defense. He can say: anyone's thoughts ought to move in the way that mine did because such movement guarantees the truth of the final thought given that the initial thoughts are true. Inez cannot say this - though, in contrast to Jeff, she can insist that the movement of her thought was defensible in some other way. The difference between the arguments of Inez and Dennis is crucial to understanding the subject matter of this section. Inez's argument has these features: the reasoning from premises to conclusion can be defended, yet, it could happen that her premises were all true, and her conclusion turned out to be false. This sort of argument is called inductive or probabilistic. We very often employ such arguments in our thinking. Dennis' argument can be defended too, but its defense has this feature: if all the premises are true, then the conclusion is bound to be true. It could not turn out that the premises were true and the conclusion was false. Arguments that are intended to have this feature are called deductive. But why did I say arguments that are intended to have this feature? Good and Bad Arguments It would be wonderful if all the deductive arguments that we used in our thinking were like Dennis': given that the premises of the argument are true, its conclusion is bound to be true. Unfortunately, this is not the case. It can, and often does, happen that we employ arguments which are intended to have this feature even though they don't. Here’s a tragically common example: 1. I am a person with rights and I have human DNA. 2. A fetus has human DNA. ------------------------------------------------Therefore, a fetus is a person with rights. We can see the mistake if we plug in another placeholder: 1. I am a person with rights and I have human DNA. 2. My fingernail clippings have human DNA. ---------------------------------------------------------------------Therefore, my fingernail clippings are humans with rights. It might not be obvious at first, but you can get a sense that the author has argued in the wrong direction. Using a bad deductive argument in one’s thinking should be distinguished from the case of using an inductive argument. Inez’s argument seemed justifiable, even though she would have readily admitted that her premises could be true and her conclusion false. She didn't expect the sort of argument she used to guarantee the truth of the conclusion. We would say that her intention was to produce a conclusion that was highly likely based on her evidence. On the other hand, the abortion argument seems quite clearly to be of the deductive sort - only faulty. It's just that genuine inductive arguments do not even pretend to meet those standards. 3