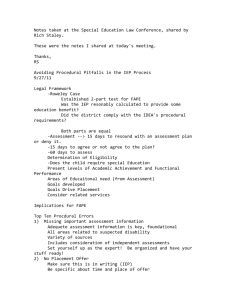

Decision in MS Word

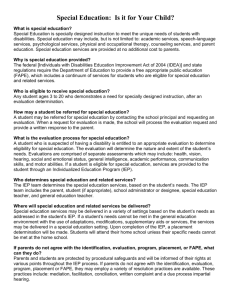

advertisement