Objectives 49

advertisement

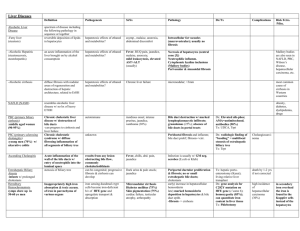

Pathology Lecture 49 Alcoholic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis of the Liver 1) Recognize that not all alcoholics get cirrhosis. More than 14 million Americans meet criteria for alcohol abuse and/or dependence (7.4% prevalence). Approximately 40% of deaths from cirrhosis are attributed to alcohol-induced liver disease. Cirrhosis develops in 10% of alcoholics. 2) Understand that not all cirrhotics are symptomatic. Cirrhosis may be clinically silent, discovered only at autopsy or when stress such as infection or trauma precipitates hepatic insufficiency. However, symptomatic cirrhosis may include malaise, weakness, weight-loss, a loss of appetite proceeding the appearance of jaundice, ascites, and peripheral edema (impaired albumin synthesis). Patients also commonly show signs of portal hypertension including vericeal hemorrhage. 3) Understand the pathologic changes of alcoholic liver disease. Changes in alcoholic liver disease include: Hepatic Steatosis (fatty liver) - a large, soft organ that is yellow and greasy. Microscopicly, macrovesicular lipid accumulation compressing the nucleus to the periphery of the hepatocyte. Alcoholic hepatitis - hepatocyte swelling and necrosis (accumulation of fat, proteins, and water), appearance of Mallory bodies (tangled cytokeratin and other proteins), neutrophil accumulation, and fibrosis. Alcoholic cirrhosis – initially cirrhotic liver is yellow-tan, fatty, and enlarged, over several years, it becomes a brown, shrunken, and non-fatty organ. Regenerative activity of entrapped parenchymal hepatocytes generates fairly uniform sized "micro nodules" creating a "hobnail" appearance on the surface of the liver 4) Recognize the histologic changes of cirrhosis. Histology: parenchymal necrosis severe enough to destroy the liver architecture with nodular rather than lobular regeneration accompanied by fibrosis. The vascular architecture is reorganized in the advanced state. 5) Vascular abnormalities in cirrhosis often control the clinical outcome of cirrhosis. In advanced cases, hepatorenal syndrome, kidney failure secondary severe vascular low flow and result in electrolyte abnormalities, are seen. Additionally, resulting portal hypertension can result in esophageal varices, splenomegaly, and ascites. 6) Understand the inflammatory changes and cirrhosis in hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease and in Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Hemochromatosis is iron accumulation in the body due to excess intestinal resorption. This results in heart damage (fetal arrhythmia), deposition of iron in endocrine cells, and stimulation of melanocyte stimulating hormone (bronze diabetes). Hemosiderosis may also occur from breakdown of RBCs and iron deposition in macrophages. Genetic mutation on chromosome 6 associated with HLA A3, 11% prevalence in US. Cirrhosis results from hepatocyte damage (inflammation and fibrosis) due to iron generation of superoxide radicals (Fenton reaction). Hemochromatosis cirrhotics develop hepatocellular carcinoma (25-30%). Wilson's disease is copper overload related liver injury due to defective biliary excretion. The genetic defect is a transmembrane copper-transporting ATPase. The increase copper in blood binds with ceruloplasmin but when this enzyme is exhausted, excess copper deposits in the iris and in neurons in basal ganglia in brain causing abnormal movement. In the liver, toxic copper levels form reactive oxygen species that may produce changes such as fatty liver, acute hepatitis (like viral hepatitis), chronic hepatitis, or massive liver necrosis (rare and indistinguishable from viral hepatitis) Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder marked abnormally low serum levels of this protease inhibitor. This gives rise to different proteins (M, N or Z types) with different severity of disease. Alpha-1 antitrypsin inhibits elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase 3, which are normally released from neutrophils at sites of inflammation. Lack of inhibition permits overactivity of these tissue-destructive enzymes. This tissue-destruction leads to emphysema and liver disease. 7) Distinguish the differences of primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis and secondary biliary cirrhosis. Disease Pathogenesis Primary biliary cirrhosis Autoimmune cholangiolytic hepatitis inflammatory injury of interlobular bile ducts, middle-aged females (9:1) Clinical presentation Insidious onset, pruritus, jaundice is late, death in 20-30 years, elevated serum cholesterol and alkaline phosphatase, abnormal MHC class I & II, T cell accumulation and B cell expansion with production of antimitochondrial antibody and polyclonal hyperglobulinemia. Duct lesions are granulomatous, late lesions include cirrhosis, intermediate changes include fibrosis in bile duct proliferation. Morphology Primary sclerosing cholangitis Inflammation and obliterative fibrosis with segmental dilation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. Associated with IBD (ulcerative colitis 70%) Male 2x >Female Does not have antimitochondrial antibody, elevated serum cholesterol and alkaline phosphatase like PBC, higher incidence of cholangiocarcinoma. Secondary biliary cirrhosis Extrahepatic bile duct obstruction, anatomic. Periductal fibrosis and segmental stenosis of extrahepatic biliary ducts Portal tract edema, inflammation in bile ducts and bile duct proliferation are seen Pruritus, jaundice, and dark urine. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.