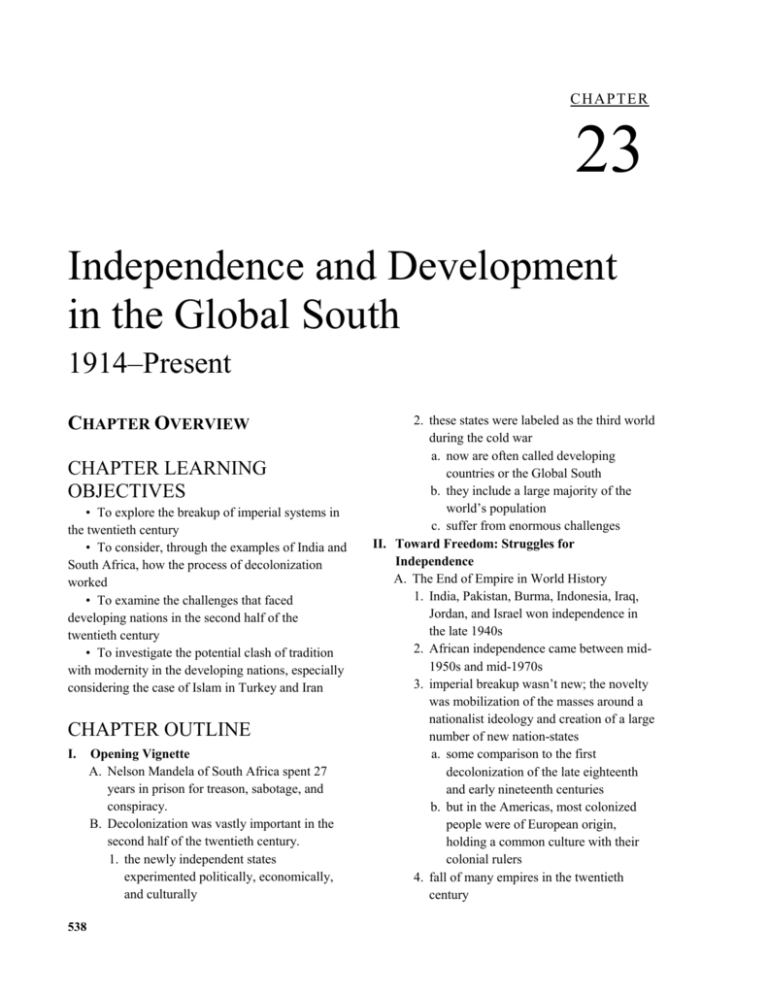

Chapter 23

advertisement