PL Object Labels - Contemporary Jewish Museum

advertisement

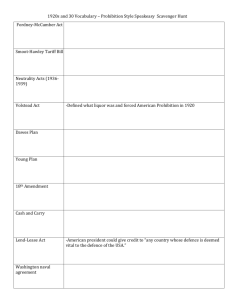

Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Introduction The Haggadah is the guiding text used during the ritual Passover meal, the seder (Hebrew for “order”). It outlines the fifteen established ceremonies that provide structure to the evening. This exhibition places The Szyk Haggadah in the context of important historic Haggadot made in diverse international communities over the last three hundred years. The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European Haggadot with their engraved illustrations, the hand-assembled kibbutz Haggadot, the contemporary Lesbian Haggadah, and a seder for Ramadan all reflect the unique circumstances of their creation and the communities in which they were used. The Szyk Haggadah, created by artist and political satirist Arthur Szyk between 1934 and 1936, draws striking parallels between the ancient Passover narrative of the exodus from Egypt and the developments in Nazi Germany in Szyk’s own time. Szyk’s illustrations and images often focused on issues of freedom and oppression, and he used The Szyk Haggadah to warn his readers of the dangers of inactivity and apathy in moments of tyranny. What unites these variations is the story they tell of the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt, and of humanity’s ongoing struggle to end oppression. During the seder it is read that “in every generation” (b’chol dor vador) participants must see themselves as if they personally came out of Egypt, in order to understand how these feelings remain relevant to us today. While each Haggadah interprets the notions of enslavement and freedom differently, together these texts ask us to recognize how these experiences persist and how, through this understanding, we can continue to pursue freedom and justice. Please note: In exhibition text the “ḥ” is pronounced with a soft “ch” in back of your throat as in chutzpah. The forty-eight original paintings for The Szyk Haggadah are presented here in the order they appeared in the 1940 edition of The Szyk Haggadah. Unless otherwise noted, all works are: Watercolor and gouache on paper Courtesy The Robbins Family Collection 1 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Arthur Szyk Arthur Szyk (pronounced “Shick”) was born in 1894 in Łódź, Poland, to a business-owning middle-class family. During his childhood, Szyk was well aware of the massacre and persecution of his fellow Jews, known as the pogroms, throughout the Russian Empire. In 1909 Szyk left Poland to study at the Académie Julien in Paris. While in France, Szyk began identifying as a “Jewish artist,” in reference to the Jewish School of Paris, which included Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, and Chaim Soutine (although Szyk likely never personally encountered these artists). At this time, Szyk became interested in the growing Zionist movement and the development of an authentic Jewish artistic style. Incorporating aspects of popular Orientalist and Eastern European folkloric imagery into his work along with the realism of nineteenth-century monumental history paintings that he would have seen growing up in Poland, Szyk most closely associated his art with illuminated manuscripts and the clear messages they carried. The result was a unique style distanced from the genres of surrealism and abstraction that were emerging in the first decades of the twentieth century. In 1913 Szyk moved back to Poland, after participating in a trip through Palestine and the Middle East organized by the Jewish cultural association Hazamir. His homecoming was cut short by his forced inscription to the Russian army in 1914. This experience encouraged his belief in the necessity of a Jewish homeland and greater protection for the Jews of Europe. In 1921, Szyk moved, along with his new family, back to Paris. At this time, Szyk began sketching out ideas for the illustration of a Haggadah, although it would be another ten years before he was able to concentrate fully on the undertaking. Szyk re-commenced work on The Szyk Haggadah in 1934. With rising tensions in Europe, Szyk was deeply concerned by Hitler’s ascendancy in Germany and its potential repercussions for the Jews. With this in mind, Szyk completed the illustrations for The Szyk Haggadah in 1936, filling them with allusions to present-day circumstances. While waiting for the book’s publication, he focused his work on propagandistic cartoons and caricatures, which were published in newspapers and magazines across Europe and the United States. In the summer of 1940, just months before the first copies of The Szyk Haggadah were available, Szyk and his family immigrated to the United States, where his cartoons were enthusiastically received. The Szyk Haggadah was finally published in England in October 1940 and distributed in a limited edition in England and the United States. Believing it his duty to fight injustice in the world, Szyk was an incredibly prolific artist and continued to produce political cartoons even after the war. Still, the Haggadah remains one of his most significant and lasting works. In a 1938 letter to his friend Cecil Roth, an eminent Jewish historian and author of the commentary in the 1940 edition of The Szyk Haggadah, Szyk wrote: “The Haggadah is the work of my life.” 2 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Dedication to King George VI, 1936 French Dedication Page, 1935 Frontispiece, 1935 The Family at the Seder, 1936 Preparations for Passover, 1935 The Seder Plate, 1935 The Order of the Seder, 1935 Kiddush—Sanctification, 1935 She-heḥiyanu, 1935 The She-hehiyanu is a traditional Jewish blessing used to express thanks on special occasions and to celebrate new experiences; it is recited at the beginning of the seder. Evident in this illustration, Szyk designed each page in The Szyk Haggadah to balance word and image. Throughout the text, passages are color-coded to reflect variations in the type of language being presented, such as prayers, instructions, and descriptions of ritual; the She-hehiyanu begins with the elaborate Hebrew lettering a quarter of the way down the page. The illustrations at the bottom of the page depict the four rituals in the Passover seder— washing the hands, dipping a green vegetable into salt water, dividing the central matzah into two, and displaying the matzot at the beginning of the seder. Just above this Szyk shows a group of individuals being blessed by an elder. The dress and farm implements of these figures help to identify them as chalutzim (Hebrew for “pioneers”)—early Zionist settlers in Palestine. The reference is reinforced by the star of David with the Hebrew word for Zion inscribed in the center. Chalutzim also appear in the illustrations for “Halleil,” “The Bread of Affliction,” and “The Seder Plate,” reinforcing Szyk’s personal belief in the establishment of a Jewish state. The Bread of Affliction, 1935 This page illustrates the beginning of the telling of the story of Passover with an invitation: “All who are hungry, enter and eat. . . . Now, we are enslaved. Next year, we shall be free.” Szyk shows Jewish slaves in the bottom left corner of the page wearing shackles and carrying a spade. On the right side, the men are free to do their own work as chalutzim, or Zionist pioneers (see also the She-hehiyanu). One of the chalutzim has a tattoo of the Star of David with the Hebrew letter Tzadi, to indicate Zion, on his forearm. Tattoos are traditionally 3 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text forbidden in Judaism; by showing one on the arm of a modern Jewish man in this illustration (which pre-dates any association with the tattoos given to Jews in Nazi concentration camps), Szyk identifies him as both secular and progressive. Baby Moses, 1936 The Four Questions, 1935 Moses Strikes the Egyptian, 1936 We Were Slaves to Pharoah, 1935 The Rabbis at Bnai B’rak, 1935 The Haggadah tells the story of five sage rabbis whose discussion of the Exodus from Egypt overtakes them for the course of an entire night. Three students in the window have come to tell the rabbis that day has come and their discussion must come to a close in time for the morning prayer. The illustration of the rabbis in discussion at the top of this page very closely resembles the composition of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (painted in the late fifteenth century). Rabbi Akiva, shown at center, is associated with Bar Kokhba, the leader of the second revolt against the Romans (132–35 CE); during the rebellion, Akiva was martyred at the hands of the Romans. Szyk shows him in the same position as Christ in Leonardo’s famed fresco, drawing a daring comparison for his readers. It is often suggested that the Last Supper was a Passover seder. The Four Sons, 1934 Szyk’s depiction of the Four Sons is notable for its treatment of archetypal Jewish characters, who appear in contemporary dress. The traditional concept of the Four Sons suggests a way to explain Passover to four different children—wise, wicked, simple, and unable to ask. Most striking is the representation of the Wicked Son. According to the tradition of the Middle Ages, the Wicked Son is portrayed as an historic persecutor of the Jews. Here, Szyk depicts this son with a whip under his arm and a mustache reminiscent of that worn by Adolf Hitler. The Four Sons (with text), 1934 God’s Promise, 1935 The passage on this page discusses the enemies who wished to destroy the Jews in every generation. To illustrate this passage Szyk chose sinister imagery, mixing skulls and modern weaponry with symbols of historic powers that have oppressed the Jews—a Roman helmet, a shield with the emblem of the Spanish kings of Castile and Leon representing the Inquisition, and the double-headed eagle of Czarist Russia, among others. Central to this image is the red snake. In Szyk’s political cartoons, snakes—which historically, in anti4 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Semitic art, symbolized the “wicked” Jews—were often depicted with swastikas running along their backs, reversing the traditional understanding of the serpent icon as an act of refusal and empowerment. With Meager Numbers, 1935 With a Mighty Hand, 1935 The Ten Plagues, 1934 Three Rabbis of Old/Dayeinu, 1935 The Exodus from Egypt, 1935 Aaron, the High Priest, 1935 Matzah and Maror, 1935 The Sea of Reeds, 1934 Le-fikḥakh—Therefore, 1935 Halleluyah!, 1935 Blessings before the Meal, 1935 Rituals with the Meal, 1935 Grace after Meals, 1935 Meeting the Messiah, 1935 Build Jerusalem, 1935 The Cup of Elijah, 1935 Other than the matzah, or unleavened bread, Elijah’s cup is one of the symbols most associated with the Passover holiday. Elijah is the prophet known for being the forerunner to the Messiah. A cup is placed on the seder table and filled for Elijah, in the hope that he may appear. Szyk’s cup depicts Elijah scorning the evil, idol-worshipping King Ahab, a king of Israel whom Elijah is said to have encountered and denounced. Pour Out Your Wrath, 1935 5 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Halleil, 1935 The First Battle with Amalek, 1935 The Great Halleil, 1935 Nishmat Kol Ḥai, 1935 Addendum Prayers, 1935 Naomi and Her Two Daughters-in-Law, 1935 This page concludes the formal part of the Haggadah with the saying, “Next year in Jerusalem.” Naomi, a Jewish woman native to Bethlehem, is shown with her two daughtersin-law, Ruth and Orpah, who are both from Moab. The husbands of all three women have died. Orpah decides to return to Moab, yet Ruth remains with Naomi and returns with her to Bethlehem. Szyk likely depicted this biblical passage because of the words that Ruth shared with Naomi at this moment: “Where you go, I will go, and where you stay, I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God.” Ruth ultimately became the greatgrandmother of King David. These women are never mentioned in the text of the Haggadah, and are rarely if ever found in other Haggadah illustrations. Szyk’s decision to include them in his book demonstrates his dedication to including Jewish heroes and activists, both men and women, in his Haggadah. King Belshazzar, 1935 Hymns and Songs, 1935 Eḥad Mi Yodeia—One, Who Knows?, 1935 Eḥad Mi Yodeia with Psalms 35:3, 1935 Ḥad Gadya, 1934 “Had Gadya” (Aramaic for “one little goat [kid]”) is a children’s song used to culminate the seder. In this allegory for the historical struggles of the Jews, the goat is often believed to represent the Jewish people, with the other featured animals, which overtake one another in turn, symbolizing persecuting nations. Here, Szyk has dedicated an entire page to the song depicting each of the ten verses. Szyk included an illustration of the David and Goliath tale in the foreground where David is represented as the ultimate hero beheading Goliath. Victorious Lions and Kids, 1935 6 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text King David, 1935 Szyk Cases Vorsatz [pastedown], 1937 Pen and ink on paper King David, late 1930s Pen and ink on paper Dedication Page to the Jews of Germany and Austria, 1938 Watercolor and gouache on paper This dedication page, along with that for the Jews of Germany, and the Jews of Lwów, was not published in the 1940 edition of The Szyk Haggadah but serves as an additional reminder of Szyk’s strong connection to his people and his intent to honor them with the masterpiece that he had completed. In order to identify himself as an advocate for these parties, he included a self-portrait in the illustration for this page, and the Dedication Page to the Jews of Lwów. Dedication Page to the Jews of Germany, 1939 Watercolor and gouache on paper Dedication Page to the Jews of Lwów, 1936 Inkjet print facsimile Moses Strikes the Egyptian, 1923-4 Watercolor, ink, and colored pencil on paper The detailed border on this work includes symbols that represent the twelve tribes of Israel, descendants of Jacob who is given the name of Israel in the Bible after wrestling all night with an angel. Szyk slightly altered two of the symbols to reflect his telling of the Passover story, emphasizing the forced labor of the Israelites. The symbol for Gad, usually a tent, is instead represented by the pyramids, which were possibly built by the Israelites in Egypt; Issachar, usually represented by a donkey carrying a burden, is instead a Hebrew slave carrying a great load on his back. Moses Tuant L’Egyptien [Moses Strikes the Egyptian], 1933 Watercolor and gouache on paper These two illustrations of Moses striking the Egyptian suggest that Szyk was considering illuminating a Haggadah as early as the 1920s. They also illustrate changes in the artist’s thinking about how he would tell his story. In the earliest painting from 1923–24, Szyk depicted Moses’ encounter with the Egyptian just before striking him; in this later version, the Egyptian is bleeding which suggests that a powerful blow has already been delivered. As 7 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text in the final version published in the Haggadah, Szyk included in the background the two Israelites who were victim to abuses by the Egyptian. Moses is shown as a hero and a savior of the mistreated Israelites in Egypt. Exodus, 1924 Watercolor, gouache, and colored pencil L’Exode [Exodus], 1933 Watercolor and gouache on paper Like Moses Tuant L’Egyptien of the same year, Szyk captioned this painting of the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt in French. The Haggadah was ultimately published in Hebrew and English, but the use of French at this time could be due to Szyk’s desire to reach a broad audience; French was the most widely spoken language up until the end of World War II. It is notable that in this painting, Szyk emphasized Moses, who can be identified by the rays of light surrounding his head, amongst the crowd of fleeing Israelites. Historically, Moses is intentionally absent from the Haggadah texts, but Szyk used Moses throughout his Haggadah as an icon of heroism. The Four Questions proof page, 1936 Print Private Collection This early printing proof of The Four Questions shows that Szyk originally painted this serpent attacking the Israelites on their march to freedom with Nazi swastikas running down its back, emphasizing the correlation the artist saw between the Israelites’ plight in Egypt and Jews’ current struggles across Europe. It is not known why the swastikas do not appear in the final printed version of the painting, but a recent X-ray of the Pharoah’s breastplate in We Were Slaves to Pharoah exposed a painted-over swastika. Frontispiece for Beaconsfield Press, ca. 1937 Pen, ink, and pencil on paper Beaconsfield Press was established by a group of Polish patrons, some of who had relocated to England specifically to facilitate the printing of the Szyk Haggadah for initial distribution in England and Israel. This version of the identity was never adopted by the press but demonstrates the importance of the press in the production of The Szyk Haggadah with the words Haggadah Shel Pesach. The inclusion of the crowned Star of David here and the image of Kind David in the drawing that also appears in this case reiterate Szyk’s interest in the image of the hero—referring to the story of David and Goliath in which the small David overcame the giant Goliath against all odds. As the second King of Israel, David conquered the fortress in Jerusalem to establish his capital at the site. David’s image appears in the final version of the Haggadah three times, although he is never mentioned in the text. 8 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Hitler as Pharoah, early 1930s Pencil on Paper The Szyk Haggadah, 1940 First edition The Szyk Haggadah, 1940 First edition Courtesy Irvin Ungar, Burlingame, California The Szyk Haggadah, 2008 Historicana Deluxe Edition Courtesy Irvin Ungar, Burlingame, California The Szyk Haggadah, 1956 Courtesy Irvin Ungar, Burlingame, California The Szyk Haggadah, 1965 Courtesy Irvin Ungar, Burlingame, California The Szyk Haggadah, 2011 Abrams Trade edition Museum Purchase Letter from Arthur Szyk to Cecil Roth, 1938 Translated from the original French My Dear Cecil, You have been asked to attend the meeting of “Beaconsfield Press” which I was not invited to. This meeting will take place tomorrow. Since my attempts to see the President for many months have been in vain, I am asking you, and I authorize you, to declare to these gentlemen the following: The “Haggada” is the work of my life. I sacrificed many years of my work as well as all my fortune (which has been very small since the war) in order to do it. I even contracted debts to complete it. My work is not finished yet, since I will have to follow step by step the excellent reproduction of the “Sun Engraving Company” until the book is published. The amount of £500, which “Beaconsfield Press” gave me, was used to pay the most urgent debts. Many months have passed since then. Today, I am completely financially ruined. As I am not well known in this country, and as there has not been any publicity of my work, I am completely unable to earn my living. My situation has become completely impossible and I am writing to the President of Beaconsfield Press in order to ask him urgently to help me, 9 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text and to immediately give me £150 in advance, as well as, the sum of £50 on the 12 th of each month until the book is published. Without this immediate help I cannot survive. It is very difficult for me to be obliged to ask these gentlemen, but as this is an urgent matter, I do not have any other choice. Obviously, the amount which I am asking for, and which I need, must be given to me in advance to be deducted from my part of the book profits, and must be given back to the Beasconfield Press profits. The original of the “Haggada,” being my property, will be the warranty of the complete amount given to me. I do not doubt that Mister Greenhill’s compassion as well as our President’s artistic qualities will push him to help me in my horrible situation and I thank them in advance with all my heart. Sincerely Arthur Szyk P.S.: If new amounts of money were [sic] Letter from Arthur Szyk to Cecil Roth, 1941 Translated from the original French My Dear Cecil, Thanks for your letter. If we haven’t written you until now, it’s not because we’re not thinking of you. By habit, I write little, and especially since my arrival in Canada and the US, I am still absorbed in my propaganda work for our war that I am not really able to write much. The pleasure that her Majesty expressed on the subject of my Haggadah gives immense pleasure. I am infinitely proud and touched. Explain to me the details, my dear Cecil. Indirectly, I had your news by the sad letter that you wrote to Doctor Rosenbach of the “Jewish Historical Society.” Our son, George, is an officer in De Gaulle’s army, in Africa at the moment, we rarely have news of him. With regards to the sale of the Hagaddah here, sadly we are unable to do anything because The Beaconsfield Press gave Dr. Rosenbach ridiculous conditions, such that it is out of the question that he is entrusted with it. He needs to have at least 50% commission at his disposal for the costs relating to the organization, which would be too great. We are very happy to know that all goes well with you. Here, all is well and the American sympathies for our cause are great. We are sure of a victory here, and in England as well. We give hugs to you and Irene. With all our hearts, 10 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Julia, Alice and Arthur Szyk P.S. My gratitude and much respect for the Binkele illustration This is the St. George Stamp by Arthur Szyk (see the envelope) Haggadot Intro The Haggadah is an ancient book of prayers, songs, biblical, Talmudic, and midrashic passages that structure the Passover seder, offering fifteen ritual steps through which the symbolic foods and traditions, as well as the story of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt are shared. Many Haggadot (plural of Haggadah) are celebrated for their beautiful and intricate illustrations, and also for their expression of the artistic, theological, political, and linguistic texture of the communities in which Jews live. The selection on view here represents a wide spectrum of historical and contemporary Haggadot, roughly grouped into three sections: illuminated, non-traditional, and popular trade editions. The selection of illuminated Haggadot includes books from the fourteenth through twentieth centuries. The Sarajevo Haggadah and Barcelona Haggadah show the emphasis on illumination in the Sephardi tradition while the Metz Haggadah and Amsterdam Haggadah reflect the dominant styles following the invention of the printing press. Trade versions of illuminated Haggadot from the twentieth century demonstrate the continued interest in the potential of illustration to deepen the meaning of the seder and to celebrate the importance of the Haggadah in Jewish ritual. Non-traditional Haggadot from kibbutzim (plural of kibbutz) and the Bay Area show distinct trends in the book’s long history of reinvention. Early kibbutzniks (Hebrew for “members of a kibbutz”) secularized the celebration of Passover, and developed new interpretations of the Haggadah appropriate for this context where the seder’s refrain of “next year in Jerusalem” was a reality. The open and inclusive nature of the Bay Area can be seen in the examples here, which reflect the growing social consciousness that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s causing a greater focus on the political aspects of Passover. The range of Haggadot commercially available today can be seen in the central vitrine in this gallery. Notable is the Maxwell House Haggadah, of which there are over a million copies in print and which is also one of the longest running sales promotions in history. Recently significant is the New American Haggadah, which was edited by contemporary writer Jonathan Safran Foer and translated by Nathan Englander. The provocative commentary depicts four voices and acknowledges the complexity of the holiday in modern life. Viewed together these Haggadot represent the diversity and continuity of Jewish expression and the continued resonance of the Passover holiday. 11 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Please continue to the reading area near the windows to read examples of the Haggadot on view here. Illuminated Haggadot Cecil Roth, trans.; Ben Shahn, ill. Haggadah for Passover, 1966 Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1965 Cecil Roth; Albert Rutherson, ill. The Haggadah: A New Critical Edition London: The Soncino Press, 1930 Barcelona Haggadah 14th century (facsimile edition, 1992) Zeev Raban The Pessach Haggadah Tel Aviv: Sinai, 1961, originally published 1955 David Geffen, ed.; Moshe Kohn, trans. American Heritage Haggadah: The Passover Experience New York: Gefen, 1992 Rothschild Haggadah 1479 (facsimile edition, n.d.) Ma’aleh bet ḥorin: ve-hu Seder Hagadah shel Pesaḥ Amsterdam, 1781 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Hagadah Metz, France: Joseph Antoine, 1767 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Hagadah shel Pesaḥ Livorno, n.d. Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Trade Edition Haggadot 12 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Sue Levi Elwell, ed.; Ruth Weisberg, ill. The Open Door: A Passover Haggadah New York: Central Conference of American Rabbis, 2002 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Rabbi Joy Levitt, Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, eds.; Jeffrey Schrier, ill. A Night of Questions: A Passover Haggadah Elkins Park, PA: The Reconstructionist Press, 2000, originally published 1999 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Maxwell House Passover Haggadah New York: Joseph Jacobs Publishing, 1991, originally published 1932 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich A. Regelson, trans.; S. Forst, ill. The Haggadah of Passover New York: Shuslinger Bros., 1944 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Rabbi Nathan Goldberg Passover Haggadah New York: Ktav Publishing House, Inc., 1966 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Shoshana Silberman; Katherine Janus Kahn, ill. A Family Haggadah Minneapolis: Kar-Ben Publishing, Inc., 2003, originally published 1997 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Rachel Anne Rabinowicz, ed.; Dan Reisinger, ill. Passover Haggadah: The Feast of Freedom New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1982 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Karen G. R. Roekard; Nina Paley, ill. The Santa Cruz Haggadah Berkeley, CA: The Hineni Consciousness Press, 1991 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Sylvia A. Rouss; Katherine Janus Kahn, ill. Sammy Spider’s First Haggadah Minneapolis: Kar-Ben Publishing, 2007 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich 13 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Yaakov Agam; Moshe Kohn, trans. The Agam Passover Haggadah New York: Gefen Publishing House, 1993 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Arthur I. Waskow The Freedom Seder: A New Haggadah for Passover New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970 Museum purchase Herbert Bronstein, ed.; Leonard Baskin, ill. A Passover Haggadah New York: Central Conference of American Rabbis, 1974 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Rabbis for Human Rights In Every Generation: Let Each of Us Look upon Ourselves As If We Came Forth out of Egypt, 2003 Philadelphia: Rabbis for Human Rights, 2003 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Chagall’s Passover Haggadah New York: Leon Amiel Publisher, 1987 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Mordecai M. Kaplan, Eugene Kohn, and Ira Eisenstein, eds.; Leonard Weisgard, ill. Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation The New Haggadah for the Passover Seder New York: Behrman House, Inc., 1953, originally published 1941 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Passover Haggadah Tel Aviv: Matan Arts Publishers Ltd., 2001 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Gérard Garouste and Marc-Alain Ouaknin Haggadah: The Passover Story New York: Assouline Publishing Inc., 2001 Courtesy of Elizheva Hurvich Haggadah for the Israeli Army 1960 Courtesy Irvin Ungar, Burlingame, California 14 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text Non-Traditional Haggadot Susie Kisber, Pat Cohn, Judith Sachs, Ray Schnitzler Haggadah shel Pesach Berkeley, 1955 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Passover Ramadan Liberation Haggadah 1991 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Judith Stein A New Haggadah: A Jewish Lesbian Seder Cambridge, MA: Bobbeh Meisens Press, 1984 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Rabbi Yoel Kahn Let Us Begin: Sha’ar Zahav’s Haggadah San Francisco: Sha’ar Zahav, 1988 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Dov ben Khayyim, ed. The Telling: A Loving Haggadah for Passover, Non-sexist, Yet Traditional Oakland: Rakhamim Publications, 1983 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Rabbi Pamela Freedman Baugh Freedom from Diety Language, A Renewal Haggadah Which Omits Words of Deification San Francisco: Or Shalom Jewish Community, n.d. Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections M. Amittai; Shraga Weill, Ill. Hashomer Hatzair Kibbutz Haggadah 1956 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Source unknown Haggadah from an Israeli Kibbutz 1947 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections 15 Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah February 13–June 29, 2014 Complete Wall Text P. Bencheim Haggadah from an Israeli Kibbutz n.d. Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Source unknown Haggadah from an Israeli Kibbutz 1946 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections K. Amir Haggadah from an Israeli Kibbutz 1976 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections Kibbutz Nahal-Oz Haggadah After 1951 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections M. Brand Kibbutz Givat-Brenner Haggadah 1955 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections M. Amitai; Moshe Profes, Ill. Hashomer Hatzair Kibbutz Haggadah ca. 1958 Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections 16