Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

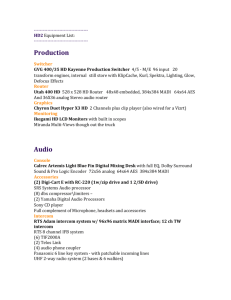

advertisement