505 submission document - Review of Food Labelling Law

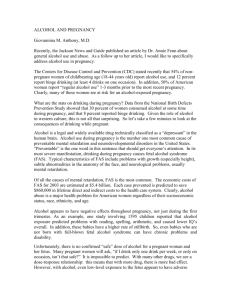

advertisement