doc - Stanford University

advertisement

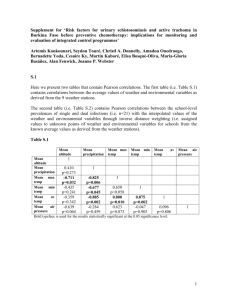

Melina Lopez 3/9/12 Humbio 153: Parasites & Pestilence Trachoma: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention Learning Objectives: -Understand and differentiate the different stages of Trachoma in the context of the WHO grading system - Understand the faults of the WHO grading system and advocate development of easy & accurate point-of-care tests -Understand pros/cons of common treatments: azithromycin and tetracycline -Understand possible surgical interventions and other solutions for trichiasis -Understand importance of administering treatment as a from of prevention as well as addressing environmental factors -Understand the prominence of human transmission and stress hygiene -Understand the importance of surveying communities and implementing the SAFE strategy -Understand ability to eliminate Trachoma with continued efforts and SAFE implementation DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATION (Slides 3-11) As part of the World Health Organization’s guidelines to treat and prevent complications of Trachoma, a grading system for clinical presentation is employed. Based upon prevalence of certain stages of trachoma in a given community, public health workers choose different courses of action. For this reason, understanding the clinical manifestations of Trachoma is crucial in order for rapid management to commence in hopes of interrupting the transmission of Trachoma. Later in this presentation the WHO Trachoma Grading System will be discussed. First, however, it is necessary to review and recognize the different stages of Trachoma progression. In examining clinical effects of Trachoma, the conjunctiva is the focal point. Looking at the anatomy of the eye, we are most concerned in examining the tarsal conjunctiva on the inner surface of the eyelid and the bulbar conjunctiva over the sclera, (See slide 3). The conjunctiva is essentially a thin mucous membrane covering the outer surface of the eye that becomes inflamed with repeated infection. The disease progresses over years as repeated infections cause scarring on the inside of the eyelid, earning it the name of the “quiet diseasei” Those living in endemic areas for a significant amount of time are most prone to Trachoma due to continual repeated infections that ultimately lead to later cicatricial disease progression. It is important to note that Trachoma is a chronic infection that begins with Active Trachoma and later develops into Cicatricial Disease. Active Trachoma is generally present in the at risk population of children <10 years oldii. Continual reinfection then leads to Cicatrical, or “scarring” disease, present in late childhood and adulthood. It follows that adult bacterial loads are usually lower than those of children, and the duration of infection and disease also declines with age, presumably as the result of an acquired immune responseiii,iv. This is in contrast to the scarring features of trachoma, the prevalence of which increase with age, reflecting the cumulative nature of the damagev. The principal signs and symptoms in the early stages of trachoma include mild itching and irritation of the eyes and eyelids, and discharge from the eyes containing mucus or pusvi, in addition to TF (Trachomatous inflammation follicular) and TI (Trachomatous inflammation intense), which will be discussed later. As the disease progresses, later trachoma symptoms include: marked light sensitivity (photophobia), blurred vision, and eye pain, in addition to complications caused by scarring6. Specifically, the WHO grading system calls for clinical diagnosis of active trachoma by everting the upper eyelid to look for the presence of 5 or more lymphoid follicles within the grading region, (see slide 6). Lymphoid follicles present as yellow-white colored dots/sacs on the conjunctiva of the everted upper eyelid. Follicles are sub epithelial collections of lymphoid cells5. Also, one can discern the presence of “Herbert’s pits,” which are circular depressions at the limbus (the conjunctiva-cornea junction) and are (due to) earlier follicles that resolved with scarringvii. Initial follicle inflammation will turn to more intense inflammation, called TI (Trachomatous inflammation intense), resulting in the appearance of intense velvety thickeningviii. This thickening makes it very hard to see blood vessels underneath mass inflammation. Then, the severity and duration of active trachoma infection predicts the likelihood of progression to Cicatricial disease in adulthood1. This leads specifically to presence of TS (Trachomatous conjunctival scarring) and TT (Trachomatous Trichiasis). Scarring initially appears as thin discrete white lines that transverse the conjunctiva. Then, as scarring progresses, conjunctival tissue coalesces, forming a thick white band near the lid margin known as Arlt's line, (see slide 8)1. Eventually, eyelid scar tissue contracts and can distort the lid margin leading to entropion (inward rolling of the eyelid) and subsequent trichiasis (ingrown eyelashes)1. Trichiasis is staged as minor (one to five eyelashes touching the globe) or major (more than five eyelashes touching the globe). Inwardly turned eyelashes scratch the corneal surface and cause repeated mechanical irritation to the eye. This presents a huge risk to developing blindness and the finding of trichiasis should prompt surgical intervention. Trichiasis can result in pannus then corneal opacification (CO). Pannus is the growth of vascular tissue over the cornea as a result of edema and ulceration due to eyelash abrasion on the cornea. It is a hallmark of trachoma but is not actually assessed in the current grading system. Later development of CO is classified by evidence of corneal opacity blurring part of the pupil margin1. Overall the gradual progression of Trachoma can be depicted in the simplified flow below: Follicle InflammationScarred eyelidseyes turn inward trichiasiseyelashes scratch surface of cornea inflammation and scarring of corneablindness Follow the WHO grading system as shown on slide 11 to classify clinical presentation of the patient’s stage of Trachoma. Later guidelines will advise what steps should be taken based upon measuring community prevalence of trachoma. WHO GRADING SYSTEM AND OTHER METHODS OF DIAGNOSIS (12-14) The current reliance on clinical signs of Trachoma can present some problems. For one, the system is very susceptible to error by medical officials who may over- or under- diagnosis Trachoma. Also, the kinetics of the disease, with a short latent phase (infection before clinical signs with the incubation period for disease), a patent phase (infection and clinical signs) and a recovery phase (infection cleared but clinical signs persist, which can last for many months) may result in misdiagnosesix,x. Moreover, Dr. Keenan of UCSF stresses the point that it is hard to differentiate active trachoma present in an individual before treatment and after treatment. Many articles confirm this difficulty in clinical diagnosis in those communities that have already received mass treatment. One may still see a few follicles and not realize that treatment has been administered already and that the patient’s condition is actually steadily improving. Instead they may call for more treatment, which could lead to a great waste of antibiotics and potentially other bacterial infections’ resistance to azithromycin (even though C. trachomatis hasn’t proven resistance to azithromycin yet). Overall, the difficulties with clinical diagnosis give inaccurate percentages of the community prevalence and affects decisions for subsequent public health implementation strategies. Perhaps some of the bigger issues, however, have to do with the fact that C. trachomatis cannot be detected in all cases of active disease, even in those cases where laboratory testing use nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) and PCR in addition to clinical diagnosis. Again, much of this is due to “kinetics” of the disease. Due to the various issues that a solely clinical diagnosis presents, other forms of testing Trachoma have been implemented. For example, laboratory assays are used for research studies and areas with low prevalence. Specifically, Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAAT) have been implemented in research studies conducted by UCSF. NAATs are highly specific and are generally used in areas with low prevalence to give a more accurate measure of Trachoma presence. However, they are not necessary in areas with higher prevalence because of higher correlation between disease and infectionxi. The benefits of NAAT tests have been praised and it has been noted that as the positive predictive value of clinical diagnosis for trachoma falls with decreasing prevalence, microbiologic diagnosis may become a more important tool1. At the same time, resources required for most laboratory tests are incredibly expensive including PCR machines generally used with NAATs. As a result, clinical grading has remained the most common form of diagnosis. There is one promising area of development for another way to diagnosis Trachoma, however: easy point-of-care tests2. A simple point of care test for C. trachomatis showed promise when evaluated in trachoma-endemic communities in Tanzaniaxii but it is not yet commercially available. This test is overall based on the same principle of tests used for Chlamydia urogenital infections. In their study, the University of Cambridge research team explained that the (point of care) assay is a dipstick immunoassay that detects chlamydial lipopolysaccharidexiii By initially taking swab samples then performing the dipstick immunoassay this test eliminates the need for expensive machinery including PCR that NAAT tests require. Also, the test is very easy to use and does not take long to train local community health workers on how to administer it. Unfortunately, later research studies have concluded that the sensitivity and specificity of this test were lower when evaluated in subsequent, larger studies in The Gambia and Senegal5. Overall, however, the research into point-of-care tests has still made great strides and can be further developed. Use of such a test is easy and accurate and can significantly help measure trachoma prevalence. TREATMENT (15-17) WHO recommends azithromycin (single oral dose) or topical tetracycline (1 percent eye ointment twice a day for six weeks) for community-wide distribution. Azithromycin is preferred because it is given as a single oral dose, although it is expensive. Pfizer has donated 135 million doses to control programs through the International Trachoma Initiative. Overall, it has been shown that a single dose of oral azithromycin is as effective as a long course of topical tetracycline for the treatment of active trachomaxiv. The call for mass treatment of azithromycin specifically has brought up questions of antibiotic resistance. However, Chlamydial resistance to azithromycin has not been documented, (although it is possible that this may be due to difficulties associated with culturing the bacterium)1. The main worry of mass treatment with azithromycin is development of resistance from other bacterial infections that azithromycin is also meant to treat. For example, strains of streptococcus have shown resistance to azithromycin2 as well as S. pneumonia, which was observed following mass azithromycin treatment for trachoma in Nepal and in an Australian Aboriginal community1. Overall, however, proven benefits of Azithromycin may outweigh potential risks. For instance, Azithromycin has proven to reduce mortality in children due to other infections, (including respiratory infections, diarrhea, and malaria). This was illustrated in a cohort including 5507 children in Ethiopia aged one to five years of age who received azithromycin for mass treatment of trachoma1. Finally, other treatments of Trachoma may target later progression of the disease, specifically at the onset of trichiasis. The aim of surgery for trichiasis is to reduce the progression to corneal opacity and blindness as a result of lashes abrading the cornea. Specifically, bilamellar tarsal rotation is used to direct the lashes away from the eye. For these surgical interventions to be employed, the WHO recommends regular surgical sessions at fixed sites once a week, with periodic outreach stations held in trachoma-endemic communities5. For areas without a surgical intervention program, epilation (eyelash removal) has been used to treat trichiasis. This may limit development of corneal opacity in patients who present with moderate to severe entropion1. Similarly, eyelid taping has been proposed as a non-surgical intervention, but this is generally a short-term measure prior to surgery5. IDENTIFYING NEED FOR INTERVENTION (slides 18-20) Currently, the WHO recommends Population-based prevalence surveys (PBPS), which provide comprehensive prevalence data and are considered the gold standard for trachoma surveys5. This method includes collecting previous surveys, written reports, hospital eye surgery records and interviewing people with local experience. Also, identification of water access and latrines in the community must be performed, in addition to other tasks outlined by WHO guidelines. PBPS can be time consuming and costly so other methods of assessing communities are being employed: TRA and ASTRA. In the mean time, population based prevalence surveys are still considered the (most) reliable source of prevalence data for trachoma, and have generally been used to prepare national control plans, and to forecast ultimate intervention goals for surgery and antibiotic treatment5 . An important component of theses surveys is clinical screening for TF (Trachomatous follicular inflammation) in children 1-9 years old. WHO criteria for mass antibiotic treatment distribution depending on prevalence rates is depicted in the table on slide 20. When mass treatment is declared necessary, the WHO recommends that treatment coverage should be between 80% and 90%xv. Mathematical modeling assuming 80% treatment coverage and 3 years of annual treatment demonstrated elimination of infection in 95% of communities5. It is imperative to note that several years of annual mass treatment is considered necessary to eliminate trachoma as noted by WHO protocol to continue annual treatment for 3 years. INTERVENTION (slides 21-24) When considering intervention and treatment, it is important to always consider the most “at-risk” group, children <10 years old. Indeed, it has been noted that frequent mass antibiotic treatment of children may confer “herd protection” to the entire community. This was illustrated in a cluster-randomized trial of over 10,000 children in Ethiopia. Results after 12 months proved the mean prevalence of infection among treated children less than 10 years old went from 48%-->3% and among individuals older than 10 in communities where the children received treatment, the mean prevalence was reduced 47% from baseline2. Furthermore, in addition to intervention in Trachoma-endemic areas by treating infection, one must also consider environmental risk factors that perpetuate infection. Specifically, one must recall the 6 D’s and the 5 F’sxvi. 6 D’s: Dryness, dust, dirt, dung, discharge, density (overcrowding) 5 F’s: flies, feces, faces, fingers, and fomites. In addition to considering environmental factors, many debate about control of humans’ transmission and control of the mechanical fly vector. Some locations have seen reduction in active trachoma by targeting the fly population. However, in other locations, the density of eye-seeking flies is insignificant and does not appear to contribute towards transmission5. Increasingly, physicians and researchers have been calling for more attention to the human transmission factor in Trachoma infection. With that, facial cleanliness, especially of children, is extremely important. In an interview with Dr. Keenan of UCSF, sanitation was stressed above targeting the fly vector. PREVENTION IN HUMANITARIAN CRISES (SLIDE 25) In terms of humanitarian crises where individuals are in close contact with each other, human-human transmission poses a huge risk factor. At the same time, women and children who may stay at refugee camps while men go to fight or to seek work are immediately at a higher risk for getting Trachoma. General sanitation is crucial for these situations so building makeshift latrines to separate human feces and to contain mechanical fly vectors is beneficial. Similarly, advocating and raising funds for a “medical cocktail” with azithromycin can help prevent many infections including Trachoma2. As noted previously, azithromycin can easily help prevent other bacterial infections. For this reason, including this antibiotic in a medical regimen administered in humanitarian crises situations with many people in close contact could prove extremely beneficial. THE SAFE STRATEGY (Slide 26) This strategy is currently the number one comprehensive recommended strategy that the WHO recommends to combat Trachoma in communities. OUTLINED FROM HOTEZ, CHAPTER 5 (source 2 in references) S: simple surgery to create a slit in the eyelid and peel back a portion to prevent further corneal scarring. This is a relatively simple procedure for which health professionals and nurses can be trained. A: antibiotics. Single dose of generic drug, azithromycin, marketed under the title, Zithromax. Zithromax can also be replaced by tetracycline, which requires topical administration for 4-6 weeks. However, the ability of just one dose of azithromycin to penetrate inside infected human cells so efficiently makes this the more attractive option. In 1998, Pfizer donated $60 million of Zithromax. F: facial hygiene. Face washing, especially among children who may be outdoors playing with many other kids, is a great step in interrupting transmission. E: environmental empowerment. Improve access to clean water, improve sanitation and latrines to reduce fly populations. Educational empowerment for community members also lends them the ability to prevent human-human transmission by better hygiene. MOROCCO 1999: Management and Prevention Success Story! Multifaceted approach to stop the infliction and impact of Trachoma -5 government ministries partnered, including health and education, local NGOs and international organizations such as UNICEF and WHO -Mobile surgery units -Administer Zithromax -Build wells and latrines -Provide education The widespread implementation of the SAFE strategy and single dose Zithromax administration made Morocco, in 2005, the first developing country to successfully interrupt the transmission of Trachoma! ITI: (International Trachoma Initiative) is sponsoring Trachoma control programs in 11 other countries including: 9 African nations (Tanzania, Ghana, Niger, Mali, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal) 2 Asian nations (Nepal and Vietnam) TRACHOMA ELIMINATION There is currently a lot of work and research surrounding Trachoma and there is a great possibly that the WHO goal to eliminate endemic Trachoma by 2020 may be reached if we continue: -SAFE implementation -Including mass drug administration (Evidence that this works is seen in the effectiveness of the Tanzanian study: “high coverage single-dose azithromycin treatment reduced the prevalence of PCR positivity among clinically active people from 58 (33%) of 174 before antibiotics to one (2%) of 49 people 2 years later,” (Solomon et al., 2004). -Develop Point of care tests for better diagnosis and regulation -Continue education to improve sanitation References: Taylor, Hugh R. and Wright, Heathcote R. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Trachoma. In: UpToDate, Basow, DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2012. i ii Keenan, J. Telephone interview. 6 Mar. 2012. Bailey R, Duong T, Carpenter R, Whittle H & Mabey D (1999) The duration of human ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection is age dependent. Epidemiology and Infection 123, 479–486. iii Grassly NC, Ward ME, Ferris S, Mabey DC & Bailey RL (2008). The natural history of trachoma infection and disease in a Gambian cohort with frequent follow-up. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2, e341 iv Hu, Victor H & Harding-Esch, Emma M & Burton, Matthew J & Bailey, Robin L & Kadimpeul, Julbert & Mabey, David C W. Epidemiology and control of trachoma: systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2010. n.p. <http://www.biomedsearch.com/nih/Epidemiology-control-trachoma-systematicreview/20374566.html>. v vi Trachoma [Internet]. [MayoClinic]: c1998-2012[cited 2012 Mar 6]. Available from: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/trachoma/DS00776. The Carter Center. Trachoma Control Program. Available at: http://www.cartercenter.org/health/trachoma/index.html. Accessed on March 8, 2012. vii The Centre for Eye Research, Australia. Trachoma Grading: Self-Directed Learning. Available at: http://www.iehu1.unimelb.edu.au/trachoma/. Accessed on March 1, 2012. viii ix Bailey RL, Hampton TJ, Hayes LJ, Ward ME, Whittle HC & Mabey DC (1994) Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of ocular chlamydial infection in trachoma-endemic communi- ties. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 170, 709– 712. x Wright HR, Turner A & Taylor HR (2008) Trachoma. Lancet 371, 1945–1954. xi Lansingh VC & Carter MJ (2007) Trachoma surveys 2000–2005: results, recent advances in methodology, and factors affecting the determination of prevalence. Survey of Ophthalmology 52, 535–546. Michel CE, Solomon AW, Magbanua JP et al. (2006) Field evaluation of a rapid point-of-care assay for targeting antibiotic treatment for trachoma control: a comparative study. Lancet 367, 1585–1590. xii Schuler, Devon. (2006). New Dipstick Speeds Trachoma Diagnosis in the Field. Special Focus-Global Opthamology. xiv Dawson CR, Schachter J, Sallam S, et al. A comparison of oral azithromycin with topical oxytetracycline/polymyxin for the treatment of trachoma in children. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 24:363. xiii xv WHO (1997) Planning for the Global Elimination of Trachoma (GET). World Health Organization, Geneva. Hotez, Peter J.. Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases : The Neglected Tropical Diseases and Their Impact on Global Health and Development. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press, 2008. p 98-99 xvi