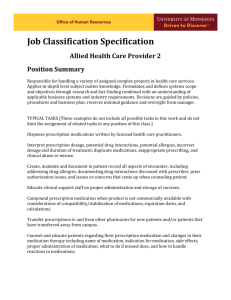

DOC - HCPro

advertisement