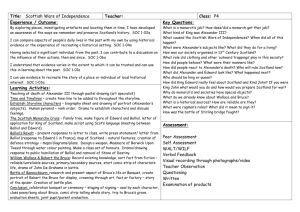

John Balliol and Edward I: Historical Debate:

advertisement

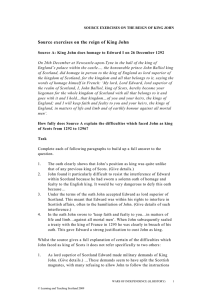

HISTORICAL DEBATE Historical debate The significance of King John’s oath to Edward The oath of homage between the King of Scots and Edward I of England changed the very nature of Scottish and English politics. The consequences of John’s oath could not have been more profo und. It not only reduced Scotland to a client status, but set the two kingdoms on the inevitable path towards war. For Edward, the oath was seen by some as the climax of several years of hard work to secure his position in the north of Britain. Certainly some chroniclers suggest this, but there is no evidence to completely back up this assertion. Yet when we look at the aggressive behaviour of Edward before, during and after the Great Cause, it is hard to see what else Edward had on his mind. King John’s oath to Edward was officially held at Norham a few weeks after his inauguration at Scone. Edward did not attend the inauguration, but he made sure that he travelled back north to Norham to hear John’s oath. The wording of the oath chosen for John by Edward spelled out the new status between Scotland and England. Edward had given the throne to King John and John was beholden to Edward for all the lands of Scotland. Not since William the Lion in 1174 had a Scottish king submitted so thoroughly. Now Edward could claim complete control over Scotland. He could claim the same rights to interfere as he was legally claim over his lands in England. In this respect the oath given by John proved to be extremely significant. Did the nobles sideline King John? Traditionally it has been assumed that the Council of Twelve had effectively taken leadership of Scotland away from King John. Historians such as Barrow have held firmly to this belief. Barrow states: ‘…their mistrust of Balliol had pushed them to the point of a sober constitutional reform…the government was taken out of Balliol’s hands’. However, there is another possibility: King John may not have been sidelined by the nobility of his realm. In fact the Scottish nobles had a long history of support and loyalty to their monarch. Could this be just another example of this? It is possible that at the Stirling parliament it was agreed by the nobility, the church and the king that all should be done to resist Edward’s demands for military service. As a show of suppor t, the nobility and church threw themselves into the ring with their king. By stepping forward, not only did they offer their support to their king, but they also put their own necks on the line along with his. WARS OF INDEPENDENCE (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 1 HISTORICAL DEBATE Why was Scotland so easily subjugated in 1296? The Battle of Dunbar, on 27 April 1296, marked the beginning of the subjugation of King John’s Scotland. On the face of it was an easy victory by Warenne, Earl of Surrey, against the common army of Scotland. The victory was a psychological defeat of the entire kingdom, and its leadership. Warenne’s forces at Dunbar were not overwhelming. However, it is to the leadership of the Scots forces that we must look for reasons for the failure of the Scots at Dunbar and the rest of the 1296 campaign. Put simply, they were found wanting. The leaders of the army at Dunbar mistook a simple reorganisation of the English forces as a retreat. They decided to abandon the strong position overlooking the English and break formation, charging the English knights as they were preparing to charge. The majority of the captured Scots taken after the battle were nobles, many of them the leaders of the Community of the Realm who had supported King John against Edward. They were the backbone of the resistance against England. With them in captivity the pressure and determination to stand against Edward was also gone. King John appeared to be unable or, some say, unwilling to take personal responsibility for the kingdom to lead the resistance after Dunbar. His Comyn-led factions were similarly weak in their leadership, retreating to their familial homes in the north east. The major castles in the south fell quickly. Although Roxburgh and Edinburgh put up something of a fight, they did not withstand Edward’s siege engines for long. Thus, without strong leadership to stiffen the morale of the Scots after the initial defeat, resistance was going to crumble quickly. It would appear that Edward was very well prepared for his 1296 invasion. He could and probably would have invaded a ye ar earlier, had it not been for the Welsh uprising. It is this that has led to historians suggesting that he was already preparing to invade Scotland before their defiance over troops serving in France. Indeed, historians also peculate that Edward may have been already aware of the treaty between the French and Scots . The Scots, on the other hand, were nowhere near ready for a war with England. The defences of Berwick had to be hastily shored up, and many of the important nobles of the Bruce faction chose to remain loyal to Edward. Added to this, the lack of experience the Scots actually had in fighting a war gave Edward’s men a considerable advantage. The common army of Scotland was summoned by their feudal lords; they had no formal military training 2 WARS OF INDEPENDENCE (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 HISTORICAL DEBATE other than a yearly ‘wappenshaw’, or weapon showing. The chain of command was somewhat blurred along family, clan and faction lines. The last time the Scots had summoned such a host had been over 30 years earlier for the Battle of Largs in 1263. Edward’s men, on the other hand, were stiffened by the presence of veterans of the Welsh wars, they had experience fighting and fighting alongside each other. WARS OF INDEPENDENCE (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2011 3