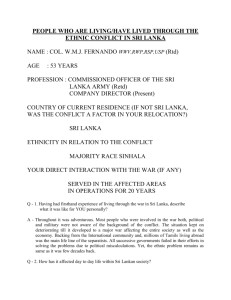

The Sri Lankan Peace Process

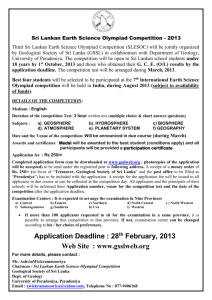

advertisement