Shelter and Infrastructure

Shelter and Infrastructure

Rehabilitation Project

Nagorno-Karabakh

Assessment

August 1998

Prepared by: Graham Saunders

On behalf of: CRS/Caucasus

3.

Contents

1. Introduction

2. General programme issues and technical resources

2.1 Staffing

2.2 Selection of target villages

2.3 Selection of beneficiaries

2.4 Building standards and the quality of construction

2.5 Contractors

2.6 Materials and suppliers

2.7 Labour

2.8 Statutory controls and regulation

2.9 Building design and construction assessments

2.10 Government investment in shelter and infrastructure rehabilitation

- Nagorno-Karabakh

2.11 Local initiatives

2.12 Scope of works - shelter and infrastructure rehabilitation to date

2.13 Property ownership

2.14 Local consultants

2.15 Use of asbestos sheeting

Programme methodology, construction procedures and administration

3.1 Community participation and self-help

3.1.1 Project oversight, the Community Working Group mechanism, and local contributions

3.1.2 Scope of works

3.1.3 Standard agreements

3.1.4 Selection of contractors and construction teams

3.1.5 Salaries and costs

3.1.6 Control of the works - site supervision

3.1.7 Quality of materials and workmanship

3.1.8 Payment procedures

3.1.9 Completion and handover

3.1.10 Defects liability, future making good and maintenance

3.2 Contracted supply of labour and materials

3.2.1 Project oversight

3.2.2 Scope of works

3.2.3 Standard contracts

3.2.4 Selection of contractors and subcontractors - tender process

3.2.5 Salaries and costs

3.2.6 Control of the works - site supervision

3.2.7 Quality of materials and workmanship

3.2.8 Payment procedures

3.2.9 Completion and handover

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 2

4.

5.

3.2.10 Defects liability, future making good and maintenance

Recommendations

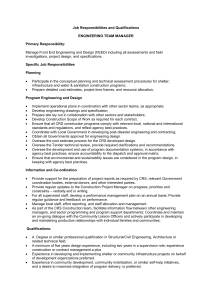

4.1 Scope of work

4.2 Selection of target villages - “cluster areas”

4.3 Phasing of the work

4.4 Establishment of Community Working Groups - CWG mechanism

4.5 Selection of beneficiaries

4.6 “Hybrid” self-help approach and local contributions

4.7 Preparation of construction assessments

4.8 Tripartite agreements

4.9 Selection of contractors

4.10 Subcontractors, local construction teams and contributory labour

4.11 Tender process

4.12 Materials and suppliers

4.13 Form of contract

4.14 Control of work - site supervision

4.15 Building standards

4.16 Payment procedures

4.17 Financial penalties

4.18 Defects liability

4.19 School rehabilitation works

4.20 Water system rehabilitation works

4.21 Disposal of asbestos sheeting

4.22 Staffing

Proposed implementation plan

5.1 Project activities

5.2 Project timetable

Appendix

A

Attachments

Summary of contacts and visits

#1

Community Working Group Protocol

#2

#3

#4

#5

#6

#7

Standard Tripartite Agreement

Contract for Construction Assessments

Standard Scope of Works

Standard Construction Assessment Form

Main Building Contract

Minor Works Contract

(Note: All the above documents may require further modification)

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 3

1. Introduction

This assessment has been carried out on behalf of CRS/Caucasus, to assist the implementation of the shelter and infrastructure rehabilitation programme entitled “Humanitarian Assistance for the

Victims of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict”.

The broad terms of reference are as follows:

To explore and advise on general programme issues and the available technical resources (staff, contractors, suppliers, local consultants, logistical support).

To develop appropriate construction administration mechanisms, with reference to the programme objectives and methodology.

To assist the overall programme refinement and initial implementation in the field.

This assessment has been carried out in Nagorno-Karabakh, complemented by background research in Armenia, with reference to both recent and current shelter and infrastructure projects.

This research is complemented, where relevant, by regional experience in appropriate methodologies and procedures.

The results of the site exploratory visits and meetings are summarised in Sections 2 & 3. Section 3 includes a particular emphasis on the relative possibilities and benefits of the utilisation of both community self-help and contracted labour and supplies. Section 4 draws on this analysis and other regional experience to provide a series of recommendations for the further development and implementation of this programme. Given the current timetable and the evident urgent level of need in the communities, Section 5 consists of a proposed timetable of activities.

2. General programme issues and technical resources

2.1 Staffing

Potential staff with appropriate engineering and construction backgrounds are available in

Nagorno-Karabakh. Based on the Soviet education system, students graduated from technical high schools and continued, with increasing specialisation, through further education. Initial work experiences varied from assisting site supervision, to overseeing the production of construction elements in pre-fabrication plants, to working in design and construction assessment offices.

Specialisation included civil engineering (roads, bridges), mine engineering, hydro-engineering

(dam and water course design), and large scale public buildings, including apartment construction.

Domestic house construction was typically undertaken on a self-help basis by the owner, with little engineering input. However, at district and village level, communal works were often undertaken by local construction teams, supervised by a local construction engineer. This has resulted in a broad division between what can be loosely described as major and minor construction projects: major public works projects, funded by the state, utilising the state design bureaux, state construction companies, and with structured site supervision and administrative procedures; and minor, village or private house-owner projects, with informal site supervision and minimal administrative procedures. Emergency repair works to houses and infrastructure works in the villages during and immediately after the conflict have resulted in a merging of these two approaches to construction, and hence many district- or village-based construction engineers now have substantial experience in terms of quantity and range of work. Extensive projects now underway funded by the military, including barracks, protective emplacements and supporting infrastructure, have also provided opportunities for rural engineers.

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 4

The experience of qualified engineers is based on Soviet construction administration procedures, last formally updated in 1984. These procedures can be readily modified, to incorporate developments in the construction industry in Western Europe and increasingly Eastern Europe, as well as the more stringent controls required by international donors and investors. This requires a fluency with construction as a process, and an aptitude to learn. The tightening of the control of the works also requires thorough project management and close site supervision. Staffing levels and the specific skill requirements thus required will be explored in 4.22.

2.2 Selection of target villages

According to the Nagorno-Karabakh Department of Social Development, a survey conducted following the 1994 cease-fire indicated that of a total of 221 settlements, 151 had been damaged.

Government-sponsored initiatives and self-help schemes had repaired approximately 3,000 private dwellings and 217 apartment buildings. By January 1998, the Department of Social Development records indicated that some 44 settlements in the districts of Askeran, Martakert, Martuni, Hadrut and Shushi were still a priority for further shelter rehabilitation. Both the Minister of Social

Welfare and the Director of the Department of Social Development had indicated that assistance should be primarily focused on villages that had been occupied by Azeri forces and where a majority of the houses had been burnt or destroyed by explosives. This included villages in

Martakert District, notably Talish and Mataghis, and in Askeran District, in particular Khramort.

The Minister of Social Welfare was also supportive of complementing the work already undertaken by the Government in a number of villages. This includes additional villages in Askeran District,

Martuni District and adjacent villages in Hadrut District. The impact of the government assistance to date is significant, aided by the rigorous criteria adopted to ensure that only priority war-victim families were included to maximise the spread of the programme. However, this has inevitably resulted in some inconsistencies, with smaller villages of less military significance failing to receive any assistance.

One practical consideration is the geographical spread of potential target villages, and access.

Although much of Askeran District is geographically close to Stepanakert, local roads are in a poor condition, and away from the asphalt roads journey times between villages are significant. Villages in the north of Hadrut District are accessed more easily from villages in Martuni District than from

Hadrut Town, which is separated by a mountain range. And Martakert District, and Martakert

Town itself, is accessed primarily by the main asphalt road through the occupied territory outside of

Nagorno-Karabakh.

2.3 Selection of beneficiaries

According to the Minister of Social Welfare, the government have accurate records of each inhabitant in each settlement, and this information is updated on a regular basis. Conversations with village mayors in several settlements indicate that in several areas, notably those villages of strategic military importance, the village mayors have good lines of communication to central government. However, it is also apparent that some shifting patterns of return, either of refugee families relocating or of individual family members returning to reoccupy damaged houses, are currently not being adequately monitored.

The government had established tight criteria for the use of its own funding for shelter rehabilitation, focusing on the families of war victims. Elderly couples, single individuals, and refugee families from territory still occupied by Azeri forces, have not been assisted to date. It should be noted, however, that most families have been consulted, and have been informed that if they have not yet been assisted they are on the list. Although village mayors have been consulted over the priority lists, the final decisions were taken centrally. In a number of villages, social cases, excluding those of families who have lost family members in the conflict, still remain unaided.

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 5

2.4 Building standards and the quality of construction

The impact of the pre-conflict Soviet construction methodology can be felt throughout

Nagorno-Karabakh, in public buildings and in other works undertaken by the state. In rural settlements, many dwellings were self-built by their owners or by local craftsmen, and although serviceable, lack good materials and thorough workmanship. The earthquake of 1988 in Armenia revealed the poor adherence to ostensibly sound construction guidelines, with substandard materials being found commonplace and negligent or fraudulent construction practices being rife.

Good raw materials can be found in both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, although poor production often results in a substandard product. The quarrying of limestone blocks and the production of mortar are two examples; the blocks used are often irregular and poorly finished, leading to over-sized and weakened joints, and many examples of mortar indicate poorly washed sand or minimal cement contents which results in insubstantial walling. A further example of the move towards expediency rather than quality is in the almost total decline in the production and use of lime in the mortar mix. Lime is a key ingredient in ensuring the mortar mix is flexible and water resistant. In Nagorno-Karabakh, limestone abounds, and up to 15 years ago lime kilns were active, both on an industrial scale and as a cottage industry in the rural areas. Mortar was traditionally made from sand and lime, with cement being a more recent additive to add strength. In many older, rural houses, earth strengthened with cut straw was used as mortar, and with well-cut stone this results in a good bond. One house visited in Nachijevanik, Askeran District, had been destroyed by fire on three occasions, reflecting previous conflicts with the Azeris and the Turks. The external, stone-built wall still remained; of the newer, block-and-mortar wall little remained. Other problems result from poor design, with timber ground floors being constructed below the level of the surrounding earth; no ventilation being provided for floor voids; inadequately calculated lintels and floor slabs, resulting in cracking in the plaster and poorly fitting joinery; and substandard detailing, which to roofs and gables could result in the loss or damage to roofs in high winds or heavy snow-falls. A further example of poor production can be seen in the variable standard of pre-fabricated reinforced concrete lintels. Problems include irregular shuttering; poor concrete mix, with oversized aggregate; lack of vibration, resulting in settlement of the aggregate; poorly formed reinforcement, and lack of spacing of reinforcement from the soffit shuttering during casting.

Indeed, the quality is so poor that rolled steel angles are often used in place of the lintels.

In general, the repair of damage due to the conflict has encouraged a virtual disregard of construction standards in the interest of speed, and as a result of inadequate skilled supervision. The

Head of the Reconstruction Department in the Ministry of Urban Redevelopment has confirmed this problem. This is exacerbated by a common problem throughout Eastern Europe and the NIS in that the government standards or “norms” are commonly quoted but rarely exist in documentary form for reference. When strictly adhered to, they result in perfectly adequate, appropriate standards of construction and finish. (This was established on a major construction project in

Albania).

In rural areas, the use of local construction teams, often without engineering supervision, has resulted in substandard work. The absence of an adequate control mechanism, with reference to the end users, has lead to dissatisfaction amongst beneficiary families. As in many cases these works have been funded by the government, the good will created by the investment has been eroded by the frustrations of having a house inferior to the previous building. This is heightened in the cases where the works were carried out by contractors from Stepanakert or Armenia, over which the families have no opportunity of redress.

However, there are notable examples of excellent work, in particular executed by a local construction team in Karmir Shuka(Krasni Bazar), Martuni District. This team had used good

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 6

quality materials, clearly used skilled craftsmen for each trade, and finished the work well to permit the owner to follow-on with plastering and other internal works. This would undoubtedly have taken more time, and required good supervision and co-ordination between the masonry and carpentry trades. Beneficiaries, village representatives and engineers consulted are clearly aware of what techniques and detailing are both technically appropriate and achievable. The challenge is to tap into this experience, and ensure that the process to both develop the scope of works and to oversee the works on site is truly accountable.

2.5 Contractors

Although the state construction companies in both Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia are still dominant, private contractors are being licensed and are beginning to compete for the small- and medium-sized contracts. Several of the private companies are in fact offshoots of state companies, with only the word “state” being omitted from the company name (for example,

“Haygyughshinnakhagits”). According to both state and private companies interviewed in both

Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, neither sector has any significant tax advantage, and that state companies are not underbidding through unrealistic overheads. For private companies, the current tax burden is in the region of 17-20% of turnover; at least one contractor in Nagorno-Karabakh indicated that he was pleased to be contributing to “his” state. The state companies do have the advantage of access to equipment, and to the government design and cost estimation offices.

Private companies, however, are able to find facilities in a market that has severely contracted since

1988, and there appears to be a healthy collaboration between the two sectors to ensure that every opportunity to create employment is taken. All companies still use the standard Soviet-era “norms” to put together tender offers, with appropriate coefficients for the respective districts to reflect their location and accessibility. However, the private companies are now responding to the competitive market, and are willing to negotiate according to market prices. Nominating contractors, amongst private contractors, is a fairly novel idea; for the larger, government-funded projects, a cross between nomination and invitation is utilised, with a government-appointed tender committee making the final selection.

In the 8-9 larger state companies in Nagorno-Karabakh, typical staffing levels are 100-120 total staff, with 7-10 qualified engineers per company. The recent yearly turnover for one medium-sized state company was $400,000. One private company interviewed, who had carried out some small but prestigious projects, had 5 qualified engineers and, until recently, had had 50 staff in total. The

Head of the Construction Department in the Ministry of Urban Development has provided a short-list of 44 companies for consideration for work in Nagorno-Karabakh, including contractors from several districts of Nagorno-Karabakh and some from Armenia. Approximately 30% of these companies are state, the remaining 70% private. Included in the private companies are some very small co-operatives, who have only recently become established.

It is reported that, in accordance with a government decree, by the end of September 1998, all state construction companies are to be privatised, with all employees being the first beneficiaries of share options. This has not been confirmed, and it is unclear what initial effect this would have on the operations of these companies.

2.6 Materials and suppliers

Basic raw construction materials, such as cement, sand, aggregate and masonry blocks (including limestone and “tufa”) can be sourced in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. During the Soviet era, other materials, notably steel, were supplied from Russia. Other materials were imported from elsewhere in Eastern Europe, with Czech ceramic tiles being one example. Electrical, water and sanitary fittings, as well as ceramic tiles, paint and other finishing materials, were produced locally to some degree, although of only average quality. Approximately 50% of the timber needs can

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 7

provided within Nagorno-Karabakh, although specific types of wood must be imported. With political issues limiting the number of traditional sources, newer sources are being explored. Iran is one example, with the road to Goris and hence south to the Iranian border being regularly trafficked by Iranian trucks. These vehicles are bringing in glass and sanitaryware, plastic piping and paint.

Materials are also being imported from Europe, with some Italian-made sanitaryware, ceramic tiles and fittings appearing in the market. Suppliers are also researching newer sources, with one importer developing contacts in Dubai as a collective point.

In both Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, pre-conflict production plants are no longer operational - the temporarily abandoned stone quarries of Askeran and Martakert in Nagorno-Karabakh being prime examples. Small-scale production of some building components is being carried out locally, for example a newly-created timber mill for the production of roofing, ceiling and flooring elements in Talish, Martakert District. However, in Nagorno-Karabakh the major issue to be addressed is the “recycling” of building materials from the abandoned Azeri settlements, particularly in the occupied territory outside of Nagorno-Karabakh. Investigation has revealed that not only are individuals looting the sites of finished materials such as cut stone blocks, roofing materials, fittings and furniture, but that the state construction companies are also sourcing their supplies of stone blocks from these settlements. Site inspection of any current construction project will reveal the use of irregular, second-hand stone blocks, often with the remnants of paint or plaster finishes. A visit to Agdam, an Azeri-majority town in occupied territory with a pre-conflict population of reputedly 110,000 people, reveals the extent of the looting. However, with such a policy being effectively condoned by the government by their inaction, and in the absence of functioning quarries, contractors and other builders have no other option.

2.7 Labour

In the currently depressed economy, there is no shortage of labour. Skilled labour is an issue, as indicated in 2.4, although this is focused on the need for skilled supervision. The leading contractors in Nagorno-Karabakh, both state and private, retain a core staff of experienced specialists, and for works within reach of their base will not recruit additional local labour. In rural areas, local construction teams have been used to carry out recent rehabilitation works, although the quality of works is thus dependent on the level of skills available locally. Typical salary levels in the leading companies are $50-60 per month for basic labouring, rising to around $80 for specialists. It should be noted that the limited salary differential reflects the quantity of work perceived to have been carried out, and the lack of emphasis on the need for higher standards of specialist works.

2.8 Statutory controls and regulation

The regulation of the construction industry still relies on the Soviet-era mechanisms and “norms”, and the efficiency of the government departments responsible for overseeing administrative procedures. As indicated in 2.4, the “norms’, when used and adhered to on site, do provide for reasonable regulation of the standards and quality of construction. Current procedures focus more on the distribution of construction projects and the tendering and selection processes. Completion and handover are, in theory, viewed as a key step at which regulations can be brought to bear, and a handover commission including representatives of all the utilities, the fire department, and the end-users, as well as the municipal engineers and architects, should provide final approval.

The Department of Construction in the Ministry of Urban Development is the primary body responsible for overseeing compliance with the regulations, with a team of 15 engineers based in

Stepanakert and individual engineers or architects based in each district. All new buildings, excluding private dwellings, should be approved by this Department. In theory, this Department, through the district engineers, should monitor works on site to ensure that the actual works

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 8

correspond with the scheme submitted for approval. However, this Department is under-resourced to face the current workload, and the approval and monitoring process is not being strictly adhered to.

2.9 Building design and construction assessments

Based on the Soviet-era state-controlled design and construction process, separate state departments were established to handle architectural and structural design and the provision of detailed cost estimates. These departments are still operational, and are handling the design work for the completion of the stalled apartment construction projects and some of the new municipal buildings. Cost estimations are being carried out for projects proceeding for state tender, and a limited number of private cost estimation services have been established for the increasing number of privately-funded projects.

2.10 Government investment in shelter and infrastructure rehabilitation - Nagorno-Karabakh

Since the cease-fire in 1994, the government have carried out the partial repair of 3,000 private dwellings and 217 apartment buildings. Preliminary assessments for this work were carried out rapidly to respond to the urgent need, and priority lists of beneficiaries were prepared in consultation with the village authorities. The construction works themselves were carried out in a variety of ways, from the use of Armenian building contractors, contractors based in Stepanakert, and locally-commissioned construction teams. As indicated above, many of the priority cases have been addressed, although with mixed results due to problems of poor workmanship. The government commission has visited the majority of the villages, and government ministers have themselves also paid visits to some of the militarily strategic villages.

2.11 Local initiatives

Although works directly engaged by the government represent by far the largest programme of investment in shelter and infrastructure rehabilitation in Nagorno-Karabakh to date, a number of other initiatives have also be undertaken. These include individual interventions by the diaspora, through to local initiatives by the beneficiaries themselves. In Khramort, Askeran District, funding from the Argentinian diaspora has resulted in the construction of 7 new dwellings and the reconstruction of 4 others. In Talish, Martakert District, 8 dwellings had been repaired by the government, and 70 through a private initiative by a US/Canadian diocesan group. This encouraged the local community to investigate its own resources, and from the limited profits of the agricultural co-operative, they have purchased materials to provide one-room temporary enclosures in a further

26 houses.

2.12 Scope of works - shelter and infrastructure rehabilitation to date

Due to the need to maximise the effect of the limited funds available, the government investment to date has concentrated on providing building enclosures only to the priority beneficiaries. This has included the making good or partial reconstruction of the main structural walls; the making good or renewal of the roof enclosure and supporting structure; the provision of a limited number of timber joinery components plus single glazing; and in a number of cases, the installation of timber floors.

Rehabilitation works have been concentrated on making good a minimum of two major rooms and the enclosed balcony. For a few families, for example in Nachijevanik and Sarnaghbyur, Askeran

District, this has also included the construction of new “starter” homes on new land either owned by the beneficiary of allocated by the village. For families who are now facing severe overcrowding as a result of changes in the family structure in the last 5/6 years, the government has also established a scheme whereby families construct the ground floor and the government will fund the construction of the upper floor. In Aranzamin, Askeran District, one family had taken up this offer,

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 9

but the government contribution to date had been minimal, insufficient to enclose the house and make it useable.

A major problem faced by all the beneficiaries of the government scheme has been the lack of personal resources to complete the works and enable the houses to be reoccupied. It is clear from the numerous inspections carried out in four districts that few families have been able to carry out any additional works except for a limited extent of ceiling enclosure and the installation of missing joinery. Government works to many of these houses have been completed for more than two years, but the families’ access to capital or in-kind contributions is clearly minimal. At best, families have resorted to looting the fittings required, such as joinery and floor-boarding, from abandoned Azeri settlements. Many of these families are therefore only temporarily occupying the houses

2.13 Property ownership

In the main towns, property rights are listed by individual occupier . In rural areas, land registries do record family title to land, but not on an individual basis. Furthermore, these records have yet to be updated, and in many cases have been destroyed during the conflict. At a local level, village mayors have assured that formal certification can be provided. Where new dwellings have been constructed to relocate families, this has either been onto land also owned by the families, or land owned collectively which has been designated for the village authorities.

2.14 Local consultants

The majority of construction specialists, either in the fields of design, cost estimation or site supervision, are currently employed in state companies or are attempting to mirror their state job in the private sector. The effects of the last ten years and the conflict have set back the transition, and few individuals have pioneered in free-lancing. However, it is clear that several of the state departments are not responsive enough, and this will lead to opportunities for those with initiative.

As indicated above, the carrying out of construction assessments is time-consuming and very labour-intensive. At least one individual has established a private service, and the carrying out of detailed assessments, to a tight brief and specific scope of work for each house, could be contracted out. Similarly, the design of new-build starter homes where required could be carried out in-house, but the use of a local architect could be considered. This could be through the state departments, or private.

2.15 Use of asbestos sheeting

Asbestos-cement corrugated sheeting has been used extensively throughout Armenia and to a certain extent in Nagorno-Karabakh. Using basic raw materials, easy to produce and simple to lay, substitutes such as corrugated galvanised metal sheeting are both more expensive and more restrictive to future modification or patch-replacement. The quality of cement used in the production was invariably of poor quality, resulting in frequent breakage. Although a known health hazard, many families continue to cut and fit new sheets to replace old.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, lapped metal roofs are also common, and the roofs of many new houses are being covered in this way. As opposed to corrugated, galvanised sheeting, the use of lapped metal is more user-friendly, permitting better jointing and better finishing at the ridge and eaves. It also is easier to work, as smaller sheets can be used, and it permits easy modification or future replacement. However, corrugated galvanised sheeting can be laid by a simple labourer, and many of the house repaired by the government have used this material. The re-use of asbestos sheeting is also very common, by both contractors and families alike. The move away from asbestos sheeting,

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 10

particularly for the partial repair of a roof, will require more investigation with the communities concerned.

3. Programme methodology, construction procedures and administration

3.1 Community participation and self-help

3.1.1 Project oversight, the Community Working Group mechanism, and local contributions

In Armenia, a sizeable number of self-help projects have been developed and overseen by local communities with a significant contribution from the community in the form of labour, materials or supporting services. These include the current UNHCR-funded programme being implemented by

CRS in Armenia to rehabilitate rural schools and water systems to benefit refugee families displaced from Azerbaijan. Oxfam have also implemented a self-help shelter programme in

Armenia for UNHCR. NRC, also on behalf of UNHCR in Armenia, have constructed new housing for refugees, which although using contracted labour did result in the participation of the families during the fitting out to shorten the construction period prior to the winter. In Nagorno-Karabakh, the involvement of the community in participating and contributing to rehabilitation projects has had mixed results. ICRC’s distribution of emergency shelter repair materials resulted in approximately 50% of the materials remaining unused, despite the urgent need for shelter enclosure. As indicated in 2.12 above, many of the beneficiaries of the government shelter scheme have only carried out limited additional works to the houses. Lack of capital and other resources short of looting from abandoned Azeri settlements is one reason given; the demands on the limited, able-bodied manpower available to both earn an income and carry out or fund repairworks is another. The temporary exodus to Russia in search of better paid employment has starved many villages of their key assets, and, invariably, better skilled workers. In terms of the development of local initiatives, there are examples of communities seeking better structured assistance than is available to suit local needs. In Talish, Martakert District, a local committee was formed to advise potential diaspora donors of the needs and the most appropriate form of assistance. This committee continued to oversee the works agreed, which included difficult decisions on the partial reconstruction of the school and how to prioritise investment in the water, electrical distribution network and shelter repair. The success of this committee is due to the vision and hard work of the village mayor, and is not necessarily a recipe for success in other villages.

The Community Working Groups established by CRS in Armenia, the local examples in

Nagorno-Karabakh as in Talish, and the substantial frustration expressed by many beneficiaries and village mayors are not being adequately involved in the government scheme to correct the errors and inconsistencies, suggest that local project development and oversight is essential.

Although local government structures at village level are overtly political, the size of the communities and the level of need does result in the engagement of all key individuals, political and non-political, in addressing the problems. School directors, long-time inhabitants, and those with acute needs, in particular mothers with children, all have a respected contribution to make, and this should be capitalised upon. It should be noted that in the absence of major assistance from outside of the village, adhoc self-help groups of neighbours and friends have already been carrying out these tasks with the limited resources at their disposal.

With regard to the type of local contribution that may be considered, it is clear that the opportunities are more limited than in Armenia as indicated above. Instead of seeing the community leading the project in terms of management and labour, including a considerable monetary contribution both financially and in-kind, perhaps it is more appropriate to consider the community participation in the construction works as a series of linked activities which also have the goal of creating other

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 11

opportunities beyond the immediate project. One idea explored in 4.12 is the establishment of specific building material production facilities. The formal establishment of the CWGs may also lead to generating ideas and resources for other projects, and the CWGs can immediately liase with the other organisations under the umbrella grant as appropriate.

3.1.2 Scope of works

Self-help, by its very nature, can be self-limiting. In terms of shelter and infrastructure rehabilitation, the costs, material resources and skills required are significant. As indicated above, all of these requirements are handicapped by the other demands on the beneficiaries and their lack of access to more than a minimum as a direct contribution. The supply of materials, excluding looted materials, is realistically limited to raw materials sourced locally (if transport is available), or materials stored prior to the conflict. In villages that were occupied by the Azeri forces, all materials were taken or destroyed. Local, specialist labour is also available in some villages, but is in demand to provide a cash income to the family or village concerned. However, individual schemes can be tailored around whatever limited contribution a family can make, either in labour, materials or other services; for rehabilitation works to schools and water systems, basic manual labour can be found as the projects are of communal benefit, and co-operatively owned machinery, if available, can be more readily adapted for such work. Furthermore, the scope of works should be strictly defined, with reference to the terms of reference and overall standards to be achieved, prior to the detailed negotiation on the donor versus local community contribution. This will prevent the temptation to trim standards of materials and agreed salary costs to expand the scope of works, often to the detriment of the project as a whole.

3.1.3 Standard agreements

Although the self-help approach usually consists of a loose arrangement of separate agreements, understandings, and contracts with key specialists or suppliers, it is essential that clear commitments are obtained for each of the elements of the programme. In the case of CRS’ rural school and water rehabilitation projects, this takes the form of an agreed list of local contributions, quantified and costed. The Community Working Group also needs to be formally constituted, with a clear definition of roles and responsibilities. These mechanisms are required to ensure that the same degree of control can be exercised by the project oversight team, in this case the Community

Working Group, as an investor would over a main contractor.

3.1.4 Selection of contractors and construction teams

The oversight by Community Working Groups in the nomination of potential contractors ensures local accountability and the inclusion of key local factors and knowledge where relevant. Similarly, the use of local construction teams in theory reduces transport overheads and capitalises on local experience and good will. It is essential that the Community Working Groups are aware that the responsibility of nominating local individuals and specialists also entails responsibility for addressing problems that arise during the construction process as well. This can lead to problems, where local favouritism, albeit supported by the use of competitive selection procedures, has relied on “understandings” outside of any written agreements. For example, in Aygut, Armenia, CRS are undertaking the partial refurbishment of the village school in partnership with the Community

Working Group(CWG). The CWG nominated local specialists to do the roofing workings, and negotiated very favourable costs. However, the CWG is reluctant to pressurise the specialists to shorten the construction period or to modify some of the work done as the costs are low and the specialists are therefore already contributing themselves to the project in the form of cut-price labour.

3.1.5 Salaries and costs

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 12

The local costs for the supply of both labour and materials is the primary area for economies through self-help and local contributions. However, as indicated in 3.1.4, this can cause overall management problems. Contributions in the form of labour should be clearly structured and costed viably. Material contributions should be similarly rigorously controlled - if a certain standard of material is required, this is what should be provided, either by direct purchase or by no-cost contribution. It is understandable that the Community Working Groups should view labour costs and the provision of lower standard materials as ways of stretching limited budgets to achieve a greater scope of works. This can be addressed through good pre-planning with the Community

Working Groups when this issues can be explored.

3.1.6 Control of the works - site supervision

The control of the works on site is key to the success of any construction project. The involvement of more than one “contractor”, whether it be through the provision of materials from one or more sources or the use of one or more independent specialist, requires adept project management and a clearly structured programme of work. There can also be a lack of clarity as to who is in overall charge of making day-to-day decisions, with the authority to make key management decisions as required. The Community Working Group effectively becomes a steering committee, assisting the resolution of off-site problems and providing guidance and instruction to the site supervisor. In

Armenia, on CRS projects to date, site supervision is undertaken by one member of the CWG, either an elected official or a local specialist. Overall programme management is provided by CRS, and administrative control over project expenditure remains with CRS. Drawing on another regional example, in Bosnia-Herzegovina, site supervision is undertaken by CRS, but under the guidance of the CWG of which CRS is a member. The local municipality also have technical representation, as well as political, in the CWG, to guide the CRS supervisor. CRS, through an agreement with the municipality, engage the municipality technical department to act as consultants during the implementation to capitalise on all the technical expertise available to the

CWG, and to ensure a balance between donor and local issues.

3.1.7 Quality of materials and workmanship

Control over the quality of workmanship and materials is dependent on the site supervisory mechanism. As previously indicated, there is a temptation to lower standards, and hence costs, to increase the scope of works. Inspection of self-help schemes in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh have indicated that standards of materials and in particular workmanship are lower than desirable.

This can be seen on schemes implemented by both non-governmental organisations and the government. This has resulted from weak or non-existent site control mechanisms, where either

CWG ambitions have compromised the works or local communities seek to achieve only what is feasible using what is available.

3.1.8 Payment procedures

Dependent on the nature of the various forms of contracts and agreements, payment procedures may take the form of bank transfers, cash payments and calculations of payment in kind. The frequency of these payments may also vary, from advance payments, to irregular payments for specific items of work, to deferred payments in kind. Examples from the CRS school and water rehabilitation project include advance payments through bank transfer for the purchase of materials, to the reconciliation of local community contributions as a paper exercise. In

Bosnia-Herzegovina, payment for some local labour contributions from beneficiary families is in the form of additional materials to the commercial value of the labour. In Albania, the community contribution of some materials was matched by bus fares to transport the materials using local public transport to the destination village. All the above approaches require sound accounting and record-keeping, and a good understanding by all involved of the overall balance sheet. This in turn

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 13

requires thorough project management by the implementing agency and the necessary resources to carry this out.

3.1.9 Completion and handover

Assuming the appropriate agreements have been used and good project management and site supervision has been exercised, completion and handover should be consistent with any approach using one main contractor. As by its nature the project has been more participatory, a final technical inspection and formal approval process should involve all involved in the construction process, end-users and those responsible for the future use and maintenance. It is also essential that to conform with relevant statutory legislation, the appropriate governmental authorities are involved in this procedure.

3.1.10 Defects liability, future making good and maintenance

Dependent on the specifics of the project, and appropriate defects liability period should have been agreed in any of the contracts and agreements entered into. It is customary for most specialists and suppliers to implicitly owe a “duty of care”, and hence to make good any defects that appear as a result of poor workmanship or materials. However, to prevent future acrimonious disputes and misunderstandings, these issues should be clarified, no matter how simply, prior to the commencement of the work. In the case of public works and utilities, this should include a mechanism for the long-term usage and maintenance of the building or system. This again should be addressed at pre-planning stage, to ensure that the funding for this, either directly or through an on-going local contribution, is clearly accounted for.

3.2 Contracted supply of materials and labour

3.2.1 Project oversight

Construction projects in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh were typically implemented through the various state departments. The brief was determined by the appropriate “investing” department - housing, education, health, state enterprise etc. The state design departments designed and engineered the scheme, and provided a costed scheme using the “norms” and the appropriate regional coefficients. These projects were in most cases projected several years in advance, so the various state construction companies were aware of the likely workload to enable them to structure yearly plans. Following handover to a state construction company, project oversight remained with the contractor. The disparate nature of the investor’s “team” meant that co-ordinated project team management would be too bureaucratic. Indeed, the administrative procedure was that the contractor was empowered to carry out detailed modifications as required - the costs were effectively fixed or accepted as being the final account according to the “norms”. Experience with

Albanian building contractors who had been part of the state system which was derived form the

Soviet model has confirmed that on completion the costs were amended to ensure that the projects came in under budget, but that the contractors could demonstrate that they had made a slight

“profit”. Overall this has therefore lead to a significant lack of accountability of the contractor, and in the current transition economy this “remeasurement” form of contract means a high degree of risk for the investor.

3.2.2 Scope of works

The use of contractors with access to specialised subcontractors permits the investor to consider a full range of works as required. It should be noted that prior to the conflict, certain state construction companies focused on particular sectors, and their management procedures and skills based were structured around these works. The construction of individual private dwellings was not

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 14

within the domain of state, and although the construction techniques are ostensibly little different from larger scale construction, the organisation, flexibility and approach to standards of finish do require modification. This is of particular importance when considering reconstruction and repair on multiple sites - partial demolition and clearance often result in new problems coming to light, and require significant, rapid, site decision-making. The problems experienced by some of the contractors who carried out previous repair works on behalf of the government confirms this.

3.2.3 Standard contracts

Most medium- and large-sized enterprises, both state and private, use a standard form of contract generated by the government and once again originating in the Soviet-era system. This document requires counter-signing by the Ministry for Urban Development. The contract briefly defines the obligations of the contractor and the investor, and the payment terms, and is common throughout

Eastern Europe. However, this form of contract lacks a detailed framework to define the methodology for dealing with the various events that are likely to occur in the life of a construction project. It is written on the understanding that the contractor has the right to determine all issues arising, from design changes, to patterns of work, to the frequency and extent of the payment, all to the cost of the investor. It is not perceived as a document to create a team or close partnership between the contractor and the investor, which is the approach taken in the US and Western Europe and now increasingly in Eastern Europe. Several private companies have expressed reservations at the simplicity of the contract and concern over a responsive legal system to support such agreements.

3.2.4 Selection of contractors and subcontractors - tender process

Contractors were typically nominated for specific projects dependent on their specialisation, or obliged to participate in government-supervised tender processes. Recent tender processes to complete buildings halted in 1988 have included state and private companies - one private contractor interviewed in Nagorno-Karabakh successfully won a contract through competitive tender against four state companies. Apparently, the private companies are in close communication, and as work is scarce and profit margins tight they attempt to avoid competing against one another. Tender evaluations are apparently carried out thoroughly, with the quality of the tender and the viability of the bid being taken into consideration as well as the tender offer and the contract period. This process is overseen by the Ministry for Urban Development.

Subcontractors are used, typically for specialised work such as water and sanitation works, heating installations, fitting out work where the volume of work is high (for example, installing large catering facilities). However, given the economic climate and the lack of major investment, many private companies are taking on this work themselves, expanding their skills base as necessary.

Other private companies consulted expressed a reluctance to use subcontractors due to the low profit margins and a lack of confidence in the forms of contracts currently used and the legal systems to support them.

3.2.5 Salaries and costs

Due to the depressed nature of the economy, salary levels in the construction sector are low.

Competition for the available jobs, and the increased number of people who now have experience from the recent investments in shelter rehabilitation, have also kept salary levels down. As indicated in 2.7, typical salaries in the private sector are $50-60 per month for basic labour, $60-80 for specialists. State and private costs are apparently similar, even including the levels of taxation.

However, this compares favourably with salary levels in other state sectors. Other costs are unrealistically low at present, as overhead costs fail to take into account the depreciation of machinery, vehicles and premises which are still perceived to belong to the state or on a long-term loan. Profit levels have been difficult to ascertain, although the Soviet-era guidelines set figures of

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 15

10-15% of the direct construction costs for profit. Private companies are also reinvesting income in new tools and equipment or orders for materials.

3.2.6 Control of the works - site supervision

Technical control of the works on site was in the hands of the contractor, in accordance with the scheme design. In theory, the investor had the right to oversee the works, but in practice this right was never exercised. Advance payments were lodged with the state bank as a guarantee, should the state company default on the contract and fail to undertake the works or continue with the works agreed. The Ministry of Urban Development, through the district engineers, also had the right to inspect the works during construction, although this right was also rarely exercised. This did lead to the common complaint that foundation works were rarely to the depth of specification require under the scheme designs, as the works were never supervised. This was tragically confirmed in

Gumri, during inspections carried out in the aftermath of the earthquake.

3.2.7 Quality of materials and workmanship

All works were to be carried out with reference to the “norms”, although evidence of numerous buildings, public and private, urban and rural, leave much to be desired. Poor detail design is also a problem, a factor that contractors were reluctant to put right if additional costs would be incurred.

One example is the absence of window cills, or the poor quality of folded metal of pre-cast elements used. The resulting water run-off has lead to the rapid deterioration of external rendered services, water penetration, and damp penetration to internal walls. No compliance with the

“norms” was enforced, with the result that poor quality construction has become accepted as being inevitable. According to a director of a leading state construction company in Nagorno-Karabakh, payment for works done was dependent on approval by the investor (see 3.2.8). Furthermore, in keeping with contemporary construction procedures, works that could not have been foreseen at the time the contract was signed were the financial responsibility of the investor, through written instruction. Works that could have been foreseen at the time the contract was signed were the financial responsibility of the contractor. Hence, any obvious errors or omissions in the original estimate were the responsibility of the contractor to check during the tender. One can only assume that the standards of work that can be seen were deemed acceptable to all. However, examples of good workmanship can be found, in urban and rural projects, and these standards should be used as yardsticks for future work until revised “norms” can be issued and upheld.

3.2.8 Payment procedures

The payment of advances was customary prior to the conflict, although the advance was effectively the transfer of funds from one state department to another. The payment of advances is still considered a necessity, to permit the purchase of materials. State construction companies have indicated advances in the order of 30%, whilst private companies have confirmed that they require advances of between 10-15% of the total project value. The primary reasons given are the lack of a capital base to commence works, the lack of readily available, affordable credit, and the common practice of the state to provide advances. Credit can be obtained, although a loan with a monthly interest rate of 4.6% was described by the private contractor who had taken the credit as being terms “better than most”. The advance payments were generally liquidated through regular deductions from further payments or, more commonly, never liquidated but subtracted from the final lump sum payment made on completion of the project.

Valuations of work done were in theory carried out jointly by the contractor and a representative of the investor using the ubiquitous “Form #2” on a trade by trade basis. As elsewhere in Eastern

Europe, contractors effectively dictated the pace of repayment with little reference to the actual

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 16

quantity of work done and certainly without reference to the quantity of work done in accordance with the standards required under the contract and the “norms”.

Regional experience has also indicated that the requirement for advances is common practice, with little reference to alternative business arrangements. An alternative approach that has been increasingly accepted elsewhere in the region is the avoidance of advances, but the assurances of regular interim payments in arrears, with an increased frequency in the first month of the project.

This is a useful indicator of the credit-worthiness of a contractor in the eyes of the local banks and the local suppliers.

3.2.9 Completion and handover

At completion, a formal commission was to be constituted to carry out a technical inspection, including representatives of the utilities, the government engineers, and the end-users of the building. It was expected that defects noted during this inspection were to be made good by the contractor.

3.2.10 Defects liability, future making good and maintenance

The construction methodology used did permit the witholding of a percentage of the balance due to a contractor, pending the final technical inspection. In some cases, this was extended to cover a period of time following completion, typically through the extremes of the weather pattern. This is standard practice in the US and Western Europe, but was rarely enforced in this region. Retention in the order of 5% was described as being reasonable, and all of the contractors discussed viewed this as both reasonable and professional. It is also customary for the contractor to owe a “duty of care” for defects arising, although few contractors are forced to meet this obligation. The future maintenance and further making good of defects was rarely planned. Indeed, in Albania, a separate project activity within an EU Phare-funded new-build housing project was the establishment of an appropriate housing association or condominium to take on this role in the absence of any official mechanism.

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 17

4. Recommendations

4.1 Scope of work

Site visits to villages in 4 districts have clarified the works carried out by the government and other donors, and the outstanding level of need. To meet these varying needs in terms of shelter rehabilitation, four typical scopes of work have been defined. Note that for each dwelling, a minimum level of accommodation of two rooms for families <4 persons, three rooms for families

>4 persons, a kitchen area and washing area is to be provided, with all necessary water, sanitary and electrical connections, as previously existed.

Type

Type A

Title

Finishing works

Detail

Internal plastering, additional joinery, additional glazing, ceiling and flooring works where required, water and electrical installations as required in the rooms to be repaired, internal painting in the repaired rooms

Type B Additional rebuilding works

Reconstruction of additional accommodation(kitchen or bathrooms), plus works as in Type A

Type C Major rebuilding works Reconstruction of main structural walls as necessary, new roof structure and enclosure, plus works as Type A

Type D New build Design and construction of a new house on a new site, to include the minimum space provision

Type A schemes, “Finishing works”, are to complement the works carried out by the government and other donors, and to make these houses fully habitable. This approach has been discussed and agreed with the Minister for Social Welfare.

Type B schemes, “Additional rebuilding works”, are also to complement previous works, primarily houses in more urbanised villages that had had internal kitchen and washing facilities.

Type C schemes, “Major rebuilding works”, are to focus on houses that have been burnt, shelled or damaged by explosive charges, but where a significant percentage of the main external walls are still structurally sound.

Type D schemes, “New build”, are for families whose homes are in occupied territory are deemed by the government to be refugees; families whose homes are damaged beyond repair and where relocation to a new site on their own land is economically more viable than repair; and families who have lost family members, are classified by the government as priority cases, and require new houses due to the changing family sizes and structures. For this latter case, only families who have been included by the government in its “one floor self build, one floor government build”, will be considered. For all Type D schemes, clarification of land ownership is required as well as the standard requirement for proof of property ownership.

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 18

4.2 Selection of target villages - “cluster areas”

Given the extensive geographical spread of the target villages identified by the government, potential villages have been grouped in “cluster areas”, loosely defined by the topography and the natural grouping dictated by access. Cluster Area 1 consists of the villages listed below in Askeran

District; Cluster Area 2 consists of the village of Karmir Shuka(Krasni Bazar) in Martuni District and the villages listed below in Hadrut District; Cluster Area 3 consists of the two villages listed below in Martakert District. The numbers of potential housing units eligible for repair are based on inspections of several typical houses in each type as appropriate, extrapolated according to local records. The totals in each village are subject to verification. Exact numbers of eligible beneficiaries in each village is are also subject to verification in accordance with the eligibility criteria as discussed in 4.5.

District

Askeran

Subtotal

Village

Nachijevanik

Aranzamin

Sarnaghbyur

Dharaz

Khramort

Type A & B Type C & D

10

7

15

75

105

6

11

13

30

Martuni

Subtotal

Hadrut

Subtotal

Martakert

Subtotal

TOTAL

Karmir Shuka (Krasni Bazar)

Drahtik

Azokh

Togh

Mataghis

Talish

6

6

1

1

14

16

45

26

71

198

3

3

4

4

50

50

114

4.3 Phasing of the works

With target villages and potential beneficiary lists still to be finally agreed, a newly-formed implementation team, and major issues over the supply and sourcing of materials to be addressed with the government, it is recommended that work is phased between each cluster area. Dependent on the approval of beneficiary lists and the availability of contracted teams to carry out construction assessments (see 4.7), works should initially commence in Cluster Area 1, with works in Cluster

Area 3 being commenced approximately four weeks later, and works in Cluster Area 2 four weeks later still. This will enable the experience gained in the start-up of Cluster Area 1 to be usefully deployed, perhaps even involving key CWG members from one area to advise the local community in a new area of the process. It will also ensure that project resources can be used more efficiently, and prevent overload and the inevitable problems and lowering of standards. This timetable would

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 19

ensure that the project was launched in all Cluster Areas prior to the onset of harshest months of winter, and permit the final assessments for the final Cluster Area to be completed in these months.

This is an optimum programme, and it may be more realistic to focus on only commencing work in one Cluster Area in 1998. It should also be noted that due to the local climate, the winter months in

Nagorno-Karabakh are not as extreme as in Armenia. Some high elevations In Nagorno-Karabakh, including Talish, failed to receive snow at village level at all during the winter of 1997-98.

Therefore, it is hoped that some site works, excluding the casting of concrete and mortar works, will continue during the winter months. Due to concerns over the quality of building materials and construction methods, it is not considered advisable to use additives and other techniques available for building in low temperatures.

4.4 Establishment of Community Working Groups - CWG mechanism

In each village, in each cluster area, Community Working Groups should be formed in accordance with CRS experience in Armenia. Discussions with village mayors indicate a high level of involvement in previous schemes, and this experience is invaluable. Other key individuals in the villages, in particular school directors, teachers and skilled craftsmen, could also valuably contribute to the process. Potential beneficiaries, especially those who have had poor experience with previous schemes, could also be involved in an informed way. And it should be noted that in many houses visited it was the women of the household who were most informed and most opinionated about the needs and the priorities. The CWGs should be formally constituted, with the roles of the local members and that of CRS being clearly defined. The CWG should be clearly empowered to oversee all aspects of the project in each respective village, including the following tasks: prioritising of the list of beneficiaries, and arranging for the signing of tripartite agreements and the provision of property and land ownership documents as required; advising on appropriate scopes of works for each house according to need; proposals for local contributions in labour and materials (with reference to eligible sources for those materials); advising on the availability of local labour, construction teams and contractors; overseeing the tender process, and sitting as a bid committee; informal monitoring on site during construction; liaison with beneficiaries during construction and the resolution of beneficiary-related issues. The CWG would also form the basis of the Commission that would undertake the final technical inspection, augmented by district governmental engineers. It should be stressed that CRS should be an integral part of the CWG, although the role of CRS includes monitoring compliance with donor agreements and the use of a veto where compliance with donor, CRS or other regulatory authorities becomes an issue.

4.5 Selection of beneficiaries

According to the Minister for Social Welfare, the government has a monthly-updated record of all priority cases throughout Nagorno-Karabakh. The provisional list prepared by the CWGs should be ratified by the Ministry, to prevent duplication of effort and to minimise discrepancies in criteria.

The Minister has confirmed that social cases should be assisted as well as “war hero/victim” families. Should the Ministry adopt a more critical and interventionist stance, a clear set of criteria should be established, with reference to the works carried out, the need to include social cases and to assist the reformation of community groups, and the pragmatic limitations that necessitate the

“cluster area” approach. The ratified list should then be prioritised by the CWGs, pending progress on detailed construction assessments and real costings through tender and local contributions.

Letters of Intent should be signed with the initial beneficiaries based on preliminary cost assessments, to determine which house should be assessed in detail.

4.6

“Hybrid” self-help approach and local contributions

The practical limitations on the possible community contributions have been addressed elsewhere in this assessment. This should be dealt with on a village by village basis, with the incentive being that the scope of works to the village could be increased commensurate with the extent of the local

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 20

contribution. On an individual basis, one approach that has had a degree of success as developed and implemented by CRS in Bosnia-Herzegovina is a direct self-build “incentive” scheme. This approach takes the fully contracted value of the minimum level of accommodation, and offers each beneficiary the opportunity to undertake one of more trades with materials provided by the contractor. An agreement specifying this work, the standards required and the time period is signed, and for this period, dependent on the work, the contractor temporarily leaves the site. If the beneficiary has successfully completed the work in time and to an acceptable standard, the contractor resumes work and the beneficiary receives additional building materials of his choice to the market value of the labour he/she has provided. If the beneficiary fails to undertake the work or to finish within the period agreed, the contractor resumes work, carries out the particular trade or trades, and the beneficiary does not receive any additional material. This approach guarantees that the minimum level of accommodation will be provided, but also allows beneficiaries who clearly do have building skills to actively participate in the reconstruction of their house. This does not result in any financial benefit to the donor, but does increase the level of local “ownership” in the project process. It should also be noted that any beneficiaries interested in participating in the self-build “incentive” scheme must be vetted by the CWG to prevent unnecessary disruption and inconvenience to the contractor. To summarise, this issue should rightly be decided by the CWG, with reference to CRS subgrant compliance issues.

4.7 Preparation of construction assessments

Following agreement on a provisional list of beneficiaries, detailed construction assessments can be carried out. A written scope of works plus a sketch plan indicating the rooms to be repaired should be agreed for each house, based on the house types, the situation on site, and the specific needs of each family. Each scope of works should be ratified by the CWG. Although the construction assessments should ideally be carried out in-house, given the workload it is recommended that this work is contracted out under tight supervision. An open tender process should therefore be held for the provision of this service; both state departments and private individuals or companies may be interested, but to maintain consistency and to minimise CRS management oversight it is recommended that one company be awarded the work per each Cluster

Area. A standard assessment form has been developed that requires only minor modification. This can be provided on disc to simplify the checking process by CRS and to permit the use of each assessment as part of the database for tracking work done and preparing valuations. These forms can be initially completed by hand, to await the establishment of the database and the appropriate staff.

4.8 Tripartite agreements

Following agreement on a provisional list of beneficiaries, and the completion of detailed construction assessments, tripartite agreements can be signed between the beneficiary, the local authority and CRS. This details the obligations of each party, including a clause regarding the release of any other temporary accommodation held and the immediate limitations on the sale or rent of the property within a defined period of time. It also obliges the municipality to ensure that there is no duplication between this scheme and the benefits of any other assistance programme.

4.9 Selection of contractors

The Ministry of Urban Development has provided a list of 44 potential contractors throughout

Nagorno-Karabakh, both state and private (see 2.5). Further potential contractors should be solicited through newspaper, radio and television adverts, and as nominated by the CWGs.

Background information should be obtained where possible from each of the contractors to enable short-lists for each Cluster Area to be determined. Structured interviews should then be carried out with each contractor, to ascertain the final tender list. Factors to be considered include: is the company legally registered, or in accordance with current legislation; has the company experience

Shelter and Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project Nagorno Karabakh

Assessment prepared by Graham Saunders on behalf of CRS/Caucasus August 1998 21

of traditional building construction; has the company directors with appropriate construction engineering qualifications and experience; does the company have the directorial capacity to manage a contract within this programme; does the company have the minimal equipment and vehicles to undertake such project; is the location of the project a problem given the main office base; readiness to accept modified construction administration procedures; access to capital or credit, and ability to work without an advance; readiness to work with local construction teams as appropriate and to accommodate contributory labour or the self-build incentive scheme; and good references.

4.10 Subcontractors, local construction teams and contributory labour

Smaller companies, local construction teams and contributory labour should be assessed as above, with a view to a role as a subcontractor. The professional requirements, experience and capacity are as 4.9. The subcontractors and local construction teams must also be prepared to enter into agreements with the main contractor, and accept working practices as structured within the main building contract. The final selection and appointment of subcontractors is the responsibility of the main contractor, although CRS has the right to nominate subcontractors and accept the responsibility of the potential impact of such an appointment on the overall works. This method would be used to include contributory labour, to be managed alongside the main building contracts.

It is preferable to have one main contractor responsible for overall progress, but through structuring the work the use of nominate subcontractors (smaller companies, local construction teams, contributory labour) can be utilised independently of the main contractor(s). See also 4.12 and the promotion of local producers of building materials and construction elements.

4.11 Tender process

Following agreement on a list of contractors for each tender, based on the Cluster Areas, tender packages can be prepared consisting of a formal letter of invitation, a tender declaration form, a copy of the scope of works and detailed construction assessments for each house as checked by

CRS, and a copy of the proposed form of contract. The tender declaration form commits the contractor to confirming that he/she has checked all of the quantities, has amended them accordingly, and is thereby confirming that the scope of works will be achieved for the price offered, irrespective of the final quantities. The contractor also has the opportunity of requesting clarification of any issues, particularly with regard to the form of contract and the control of the works. Any works that the contractor considers to have been omitted can also be submitted as a separate cost for discussion. A minimum period of two weeks should be allocated for tender preparation, and a fixed deadline strictly adhered to. Formal tender opening should be carried out in the presence of the CWG, although detailed analysis of the tender returns for errors, inconsistencies and omissions should be carried out by CRS. This analysis, in a tabular format, should then be re-presented to the CWG with a recommendation based on the interviews and the tender.

Dependent on the number of houses, each contract should ideally be restricted to a maximum of 30 houses. In any one Cluster Area, the allocation of houses should be based on a combination of proximity and the individual house cost.

4.12 Materials and suppliers