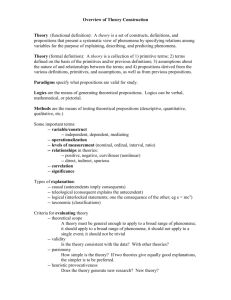

A piece of wisdom

advertisement

“A piece of wisdom about doubt”: Akeel Bilgrami on hinge propositions. The arena in which Akeel Bilgrami and Crispin Wright (1985) debate is epistemology, particularly the role granted to ‘hinge propositions’. First I will outline their approaches. Thereupon, I will put forward my thoughts regarding the propositions Wittgenstein explores in On Certainty. I. The sceptical challenge regarding the external world is the following: Perceptual knowledge depends (conceptually) on a more basic knowledge: the subject has to know and has to be able to justify that his perceptual experience is immune to any possible form of deception. On behalf of G. E. Moore, James Pryor responds: If I have a given perceptual experience that p is the case, I have prima facie an immediate justification that I know that p. Such immediacy counters one of the sceptical premises while the notion of prima facie concedes the other: p is defeasible only if positive empirical evidence proves that the subject is deceived. From a pragmatist approach, Bilgrami holds that it is possible to deal with the sceptic in another way, but previously makes three critical observations to the Pryor-Moore reading on the issue. First, to accept the terms of the challenge is to accept that there is a difference between the perceptual belief and the experience that justifies it. This enables questioning the transit from one to the other and, consequently, questioning all beliefs regarding the external world. Second, the reading does not account for the fact that the prima facie qualifier as used by Pryor in a fallibilist vein, implies a positive presumption in favour of p, which would only be defeated if there is positive empirical evidence that the person is being deceived. Third, the reading does not consider that the terms that have been conceded can actually be uncoupled from the more general idea (what is at stake is the class of beliefs concerning the external world) of positive presumption. Bilgrami, instead, rejects the distinction between experiences and perceptual beliefs, he focuses on the objective of the doubt (the perceptual beliefs themselves) and exploits Pryor’s insight of positive presumption in favour of an anti-Cartesian epistemology: (1) There is a positive presumption that our perceptual beliefs are true unless there is (positive) counter empirical evidence against them. Bilgrami talks neither of experiences nor of a justification on the basis of these experiences (at least not at the outset). Doing so would be engaging in the sceptic game. He only says that perceptual beliefs are true. He inverts the terms of the challenge. Rather than having the subject justify his beliefs, he has the challenger justify his doubts. Accordingly, Bilgrami derives a more general principle from (1): (2) We need positive empirical evidence to the contrary before we give up on something in the name of doubt. 1 Now, while not straying from the epistemological tradition, the principle admits an additional generalization. Rather than restricting it to perceptual beliefs, it can encompass all beliefs of which we are certain for the length of our inquiry. Once the distinction between true beliefs and beliefs we hold with some uncertainty (hypotheses) has been made, the idea is that nobody would doubt things like, for instance, that the Earth is round. Therefore: (3) A contemporary inquirer will refuse to doubt those beliefs of which he is certain unless someone produce specific positive evidence to the contrary. It so happens that (3) agrees with (or is derived from) the pragmatist slogan that confronts the philosophical tradition, i.e., “Nothing makes a difference to epistemology which does not make a difference to inquiry”. It falls together with it because although the slogan does not mention doubt, it certainly rejects the logical possibility of dream, deceit or radical illusion scenarios by denying that they would introduce change in the inquiry. But Pryor rejects it too; he stipulates that only empirical evidence can prima facie defeat the justification, hence precluding all a priori speculation. Thus , to all those who endorse that such scenarios “produce a difference” in epistemology, Bilgrami replies that principles (1), (2) and (3) reject, as does the slogan, that a speculation like those of the first two Cartesian Meditations should be understood as a form of inquiry. (I skip presenting Crispin Wright’s article.) Bilgrami’s interest lies in comparing Wittgenstein’s conclusions with the pragmatist proposal he intends to outline. If Wright is correct, the analogy with the elections would touch on the crux of Wittgenstein’s response to the sceptic: type (iii) propositions (There is an election going on) provide an institutional frame that enables seeing proposition (i) (Mark with an X) as evidence of (ii) (James has just voted). In the same manner, proposition (iii) (The material world exists) enables the passage of (i) (I experience my hand) to (ii) (I have a hand) and there emerges the conventional status of Wittgenstein’s response to the sceptic. Wright quotes Wittgenstein’s characterization of type (iii) propositions as follows: “That is to say, the questions that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which those turn.” “That is to say, it belongs to the logic of our scientific investigations that certain things are in deed not doubted.” “But it isn’t that the situation is like this: We just can’t investigate everything, and for that reason we are forced to rest content with assumption. If I want the door to turn, the hinges must stay put.” (oc: 341-344). Were the function of the so-called “hinge propositions” what is mentioned in the quotations above, then Bilgrami’s project of taking the Pryor-Moore strategy to a more general epistemological level includes something very close to it. In his proposal, there are propositions that we are certain of and that do not require any justification, and propositions (speculations, hypotheses) that scientific inquiry considers as to be investigated. It is only regarding the latter that the need for justification arises. While the inquiry takes place, we can not doubt the propositions of which we are certain. They provide the standard with regard to which the inquiry is carried out; they enable an evaluation of the consequences 2 of our inquiry. And it is natural that what function as a standard in an inquiry will not be subject to doubt, at least while the inquiry is ongoing. Now, on behalf of Wittgenstein, Wright claims that such propositions are not to be questioned even in the event of positive empirical evidence against them. They are not to be questioned because the evidence is not relevant, as he says, hinge propositions do not establish “facts”. Thus Wright insists that we can get rid of an institution or practice, but not because a doubt from a said source is able to eliminate them. For Bilgrami, on the contrary, the propositions that we are certain of are only immune to a priori scenarios (logical or metaphysical possibilities) but cease to be so when empirical evidence comes into play. Their institutional role does not exempt them. Unlike Wright, Bilgrami holds that hinge propositions are empirical and, as such, belong to the fact discourse. Unlike Wright, he understands that they are not restricted to expressions of the type “There’s a material world” (iii) or “This is my hand” (ii) but that they encompass “all beliefs we hold with certainty”. Again, unlike Wright, he rules out type (i) propositions from his epistemological outlook. This way, Bilgrami confronts both the relativist and the sceptic with principle (1), by denying that it is legitimate to say that we can never be certain of the truth of any given empirical belief. With principles (2) and (3), he rescues from On Certainty the idea that hinge propositions are not subject to doubt, at least while scientific inquiry is ongoing. With (1) and (3), he insists on something he has pointed out before: that truth is the goal of the inquiry. Meanwhile, principle (2), “a piece of wisdom about doubt”, enables him to invert the terms of the sceptical argument thus forcing the challenger to justify his doubts about perceptual beliefs. Bilgrami is only willing to consider experience if specific evidence of deception is submitted. Only then might type (i) propositions be introduced. Interestingly enough, his three principles enhance the pragmatist slogan making it more significant. II. In On Certainty Wittgenstein discusses those propositions whose truth Moore claims to know, i. e., that there are objects; that this is my hand; that the Earth exists since long before I was born. But, “When Moore says he knows such and such, he is really enumerating a lot of empirical propositions which we affirm without special testing; propositions, that is, which have a logical peculiar role in the system of our empirical propositions.” (136) (my underlining). What is their peculiar role? That we take them for granted without asking why we do so. We hold them to be unquestionable, literally ‘doubt-free’, although we do not have good reasons in their support. We do not test them nor mention the word “perhaps”. We do not learn them explicitly or arrive at them by means of an inquiry. No one ever taught us that our hands do not disappear when we sleep or that this mountain was right there years before our birth. The child brings in this information (he “swallows it down” says Wittgenstein more eloquently) along with the rest of the things he learns (143). “I do not explicitly learn the propositions that stand fast for me. I can discover them subsequently like the axis around which a body rotates. This axis is not 3 fixed in the sense that anything holds it fast, but the movement around it determines its immobility.” (152) Tacitly, implicitly, we bring in a web of propositions that is beyond all reasonable doubt, a system that gives us the certainty and confidence on which our linguistic and non-linguistic practice rests. The system allows us to act and also to think (411). It constitutes our world-picture, our frame of reference, our way of life. Yet that set of convictions or “fundamental attitudes” (238) –though it is beyond what is justified or unjustified (justification has an end 192)– is not, philosophically speaking, a legitimate epistemic base. Rather, “one might say almost that these foundation-walls are carried by the whole house” (248); (253; 166). “I should like to say: Moore dos not know what he asserts he knows, but it stands fast for him, as also for me; regarding it as absolutely solid is part of our method of doubt an enquiry. “ (151) Moore seems to have overlooked how highly specialised the use of the expression “I know” is. He does not distinguish the philosophical use from the everyday one (638), the distance from error to madness (155), the abyss between reasonable doubt and nonsense (115; 221). He fails to notice the difference in category between knowledge [Wissen] and certainty [Sicherheit or Gewiβheit]. Consequently, he uses the expression “I know” in a context in which it does not belong to. “For when Moore says ‘I know that that’s….’ I want to reply ‘you don’t know anything!’ –and yet I would not say that to anyone who was speaking without philosophical intention. That is, I feel (rightly?) that these two mean something different. (407) “I, L. W., believe, am sure, that my friend hasn’t sawdust in his body or his head, even though I have no direct evidence of my sense to the contrary. I am sure, by reason of what has been said to me, of what I have read, and of my experience. To have doubts about it would seem to me madness–of course, this is also in agreement with other people; but I agree with them. (281) “But why am I so certain that this is my hand? Doesn’t the whole languagegame rest on this kind of certainty [Sicherheit]? Or: isn’t this ‘certainty’ already presupposed in the language-game? Namely by virtue of the fact that one is not playing the game, or is playing wrong, if one does not recognize objects with certainty.” (446) What I know I do not tell myself. I can be certain [gewiβ] of what I say and do, I can be completely sure [Sicherheit], but both things are subjective (174; 245). To the contrary, “What is a telling ground for something is not anything I decide.” (271) “There are countless general empirical propositions that count as certain [gewiβ] for us.” “One such is that if someone’s arm is cut off it will not grow again. Another, if someone’s head is cut off he is dead and will never live again.” (273-4). [However], “’Knowledge’ [Wissen] and ‘certainty’ [Sicherheit] belong to different categories. [..] What interests us now is not being sure [Sichersein] but knowledge. That is, we are interested in the fact that about certain empirical propositions no doubt can exist if making judgments is to be possible at all. Or again: I am inclined to believe that not everything that has the form of an empirical proposition is one.” (308) 4 “It might be imagined that some propositions, of the form of empirical propositions, were hardened and functioned as channels for such empirical propositions as were not hardened but fluid; and that this relation altered with time, in that fluid propositions hardened, and hard ones became fluid.” (96) The traits of such propositions appear to be the following: i) the lack of doubt as the possibility condition of judgments –which implies that specific reasons are needed to doubt (458; 509); ii) the fact that no reasonable person would even dream to question; iii) that they function as norms of description rather than factual propositions (401-2) –even when the limits are not clear (319) and the relationship might be altered with the passage of time (336); iv) that they are the basis of our action and our thought: we act and think according to them (411; 476; 510-1). Now, those traits do not apply to knowledge, which is also a system (410). A system containing speculations and hypotheses and having its own rules. If I claim to know something, it makes sense that others ask me how I know it (550; 588) and then I reply because such and such. Since I can make a mistake, I have to give good reasons (333), grounds for my claim (484; 504; 574). I have to be able to show the evidence I have or as in mathematics to offer a proof. Those are, in my opinion, the criteria that justify saying that a person knows what he claims to know. However, “I cannot say that I have good grounds for the opinion that cats do not grow on trees or that I had a father and a mother” (281). There lies, I believe, the difference in category between knowledge and certainty, two differents language-games. “Certainty [Gewiβheit] is as it were a tone of voice in which one declares how things are, but one does not infer from the tone of voice that one is justified.” (30) Moore did not distinguish reasonable from unreasonable doubt, and likewise, he confused error and madness, which seems to have led him to seriously get engaged in the sceptic debate. (Something I understand Wittgenstein avoids doing in On Certainty.) If I doubt whether this is actually my hand, “how could I avoid doubting whether the word ‘hand’ has any meaning”? (370) “The argument ‘I may be dreaming’ is senseless for this reason: if I am dreaming, this remark is being dreamed as well –and indeed it is also being dreamed that these words have any meaning. “ (383) Let us suppose that I were sure that a given event took place on a certain year and then I realize, by reading a well-known book, that I was mistaken “I should alter my opinion, and this would not mean I lost all faith in judging” (66-7, my italics). But if I claim, with the same conviction, that my name is J.V., that I have three children, that I live in Buenos Aires, and it turns out that what I say is wrong… “I should not call this a mistake, but rather a mental disturbance, perhaps a transient one” (71). But then how could I trust any other judgment of mine? (490). The point here is that I cannot free myself from them “without toppling all other judgment with it” (419; 492; 494). “One says ‘I know’ when one is ready to give compelling grounds. ‘I know’ relates to a possibility of demonstrating the truth. [..] But if what he believes 5 is of such a kind that the grounds that he can give are no surer than his assertion, then he cannot say that he knows what he believes.” (243, my underlining) This, as I see it, is the reason why Wittgenstein rejects type i) experiential propositions in response to scepticism regarding the external world. Why should seeing my hands have to count as stronger evidence than saying I have them? (250) Why should I trust present evidence if I cannot trust any other one? (302). In my reading, unlike in Wright’s, Wittgenstein did not in the least admire Moore’s articles on the topic. “One might simply say ‘O, rubbish!’ to someone who wanted to make objections to the propositions that are beyond doubt. That is, not reply to him but admonish him“ (495). “The queer thing is that even though I find it quite correct for someone to say ‘Rubbish!’ and so brush aside the attempt to confuse him with doubts at bedrock, –nevertheless, I hold it to be incorrect if he seeks to defend himself (using, e.g., the words ‘I know’)”. (498); (521) Now for me the most problematic issue in On Certainty is the following: Are the hinge propositions true? If I say, for instance, “The standard meter in Paris is one meter long” (PI: §50), is it true? Doubtfully so, because if something acts as a rule or standard measure it seems pointless to attribute a truth value to it. However, had I said the Paris standard meter is ten meters long, wouldn’t I have made a false statement? On one hand Wittgenstein says: “But I did not get my picture of the world by satisfying myself of its correctness; nor do I have it because I am satisfied of its correctness. No: it is the inherited background against which I distinguish between true and false.” (94). “Giving grounds, however, justifying the evidence, comes to an end –but the end is not certain propositions’ striking us immediately as true, i.e. it is not a kind of seeing on our part; it is our acting, which lies at the bottom of the language-game. (204) “If the true is what is grounded, then the ground is not true, nor yet false. (205) But on the other hand, he also says: “The truth of certain empirical propositions belongs to our frame of reference.” (83) “If someone asked us ‘but is that true?’ we might say ‘yes’ to him; and if he demanded grounds we might say ‘I can’t give you any grounds, but if you learn more you too will think the same’. If this didn’t come about, that would mean that he couldn’t for example learn history.” (206) “In general I take as true what is found in text-books, of geography for example. Why? I say: All these facts have been confirmed a hundred times over. But how do I know that? What is my evidence for it? I have a worldpicture. Is it true of false? Above all it is the substratum of all my enquiring and asserting. The propositions describing it are not all equally subject to testing.” (162; my underlining). ”To say of a man, in Moore’s sense, that he knows something; that what he says is therefore unconditionally the truth, seems wrong to me. –It is the truth only inasmuch as it is an unmoving foundation of his language-games (403). 6 I hesitate between saying that hinge propositions (which are not part of our knowledge system) lack truth value and saying that we treat them as true while recognizing that “the same proposition may get treated at one time as something to test by experience, at another as a rule of testing.” (98). But I hesitate because, isn’t a proposition true or false when we consider it to be empirical and doesn’t it cease to have these values when we treat it as a rule or as a grammatical proposition? Everywhere Wittgenstein draws the grammatical-empirical division and offers keys to differentiate them: a proposition is grammatical when it is very difficult to imagine counter evidence for it or when the evidence we can get is not more steadfast than the proposition we wish to validate. On the contrary, when we deny an empirical proposition we give way to another empirical proposition, and we understand both of them. But what is the outcome of denying a hinge proposition? What would be like for it to be otherwise? Yet again, it makes sense to say that I know p when it also makes sense for somebody else to say he does not know p. Therefore, we talk of knowledge when doubt is an intelligible possibility. For this reason I do not see that the notion of “true belief” (which brings along analyticity issues) can easily be placed in the realm of certainties [Gewiβheit]. I am more inclined to say that we rather take them as true in our daily lives and during our inquiries. Finally, unlike Wright, I consider that the scope of our system of reference, our Weltbild, greatly exceeds examples of the type “This is my hand” or “There are objects.” I also believe that there are degrees among the propositions we take for granted or would find very hard to give up. At any rate, what is called the background or bedrock level includes, in my opinion, 1) the so called “avowals” (“My head aches”, “Mi name is J.V.”, “I’m waiting for X”); 2) propositions about colours (“This colour is green”), and 3) several propositions mentioned in On Certainty: “I have never been in the moon”, “My body has never disappeared and reappeared again after an interval”, “I have flown from America to England in the last few days”, “Now I am sitting at a table and writing”. And also, “The sun is not a hole in the vault of heaven”, “Water boils at circa 100° C” (though maybe at another level). The four traits attributed earlier to the hinge propositions apply to all the above cases. However, I’d like to add an additional feature. It makes no sense to doubt, to request for or give reasons for them. Faced with 1),2) and 3) no one in his right senses would ask “How do you know?”, “Are you sure?”, “Do you have evidence?”, “Can you prove it?“ I find it highly revealing that all of them are criterionless propositions. By this I mean the following: Wittgenstein makes use of such questions to shed light onto the piece of grammar he is interested in clarifying. And with them he manages to establish the criteria of correctness of an alleged (in this case) epistemic proposition. What is striking about hinges (as with avowals and propositions about colours) is that those questions are totally out of place. Actually, we would be puzzled if somebody posed them to us. No one has reasons to doubt, justify or give grounds for what is affirmed in this class of propositions. In other contexts he poses different questions. What are the criteria for saying that someone understands something or the criteria for saying that a proposition is true? Or even what are the criteria for saying he could have proceeded 7 otherwise, i.e., that he could be held responsible?, Was he in a position to choose? Had he options? Did it happen by chance? As a final comment, I would like to say that although I consider Bilgrami’s pragmatist project subtle and original I do not wish to delve into it now; rather I would like to outline some similarities and differences between his project and Wittgenstein’s On Certainty. According to Bilgrami’s hinge propositions, a certain class of our beliefs 1) are true and 2) amount to knowledge without 3) any need for justification, “since without positive evidence to the contrary which might raise certain specific doubts about them, there is no need to worry about justifying them”. If I’m not mistaken, Wittgenstein could have accepted 1), denied 2) in its philosophical use, reaffirmed 3) and agreed with Bilgrami to include type ii) propositions among hinge propositions, namely: “I will not doubt my perceptual beliefs that I have a hand, that I am sitting with a pad and a pen, that there is a window in front of me, that there are leafless trees outside, etc., unless someone gives me specific evidence of deception” ( Bilgrami, p. 7) I also believe that for both of them the core of such propositions is the absence of doubt. For Bilgrami, however, hinge propositions are empirical, concerning factual discourse while Wittgenstein, on the contrary, grants them a grammatical status –that of norms of description, standards or rules. It is true that when Wittgenstein refers to the grammatical-empirical relation with recourse to the metaphor of the river and the river-bed (97-99), he does not draw a sharp distinction, thus admitting that their roles could be interchanged. But not simultaneously. If we use a proposition in a grammatical manner, we do not use it empirically. This is made clear when he mentions the fluctuation between criteria and symptoms (PI: 354). The sentence “Acid turns litmus paper red” used to be considered a norm because that was the definition of being an acid but later on that definition changed. In cases such as this one, Wittgenstein talks of a “defining criterion” (he does so when he introduces the notion of criterion in the Blue Book, in relation to the term “angina”) as opposed to what would be an empirical concomitance, i.e. a symptom. But only in such cases when they function as a norm and scientific terms are their domain, I believe that criteria could be included in the sphere of hinge propositions. Wittgenstein appears to recognise levels of revisability in our Weltbild. On one hand, we have propositions that are almost impossible to give up without “toppling all other judgments with it”. Then an avowal like “My head aches” appears to be unshakeable. But I could feel pain in an arm that had just been cut off, thus cancelling the corresponding avowal. Or let’s take the case of “My name is X”. It is a constituent element of the language game of proper names that people will not question their given name. But if one day X finds out that she is a child of disappeared parents and discovers her real name, then her former belief, firm until then as the axis of her life, will have to be abandoned (not without having to throw away quite a few other ones). It is true that such an avowal is abandoned in the face of specific empirical evidence. However, believing that I am a woman, that there are colours or that the Earth exists since long before I was born, do not have the same degree of revisability. 8 Both Bilgrami and Wittgenstein revert the terms of the sceptic argument. Or rather, Bilgrami clearly does so while Wittgenstein, in my view, shows the sceptic’s complaints to be senseless and does not try to persuade him with any additional argumentation. (I do not endorse Kripke’s (1982) version and I do not support those who hold that Wittgenstein attempts to refute scepticism concerning other minds with the notion of criterion –in this case behavioural). In my understanding, he holds that our relation with other minds and with the external world is not a cognitive one. We do not have ‘opinions’ or ‘beliefs’ on these matters. Knowledge is not at stake. Rather, it has to do with a spontaneous “attitude” towards the world and other people (Zettel: 384). As I see it, the most contentious point between both approaches lies in that Bilgrami’s hinges are empirical, i.e., they belong to the fact-discourse, whereas Wittgenstein’s hinges –and here I agree with Crispin Wright –are grammatical norms. These different positions, I would suggest, might be explained by an underlying disagreement in their respective ideas about language. If that is so, a settlement between them might be very difficult to reach. Julia Vergara 9