In our view, population aging will lead to profound changes in

advertisement

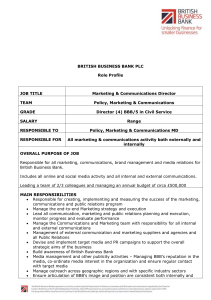

The Impact Of Population Ageing On Sovereign Ratings For Central And Eastern European Sovereigns1 Marko Mršnik2 Abstract In our view, population aging will lead to profound changes in economic growth prospects for countries around the world, alongside heightened budgetary pressures from greater age-related spending needs. In the absence of appropriate budgetary adjustment, additional reforms to pension and health-care systems, or structural measures to improve sovereigns' growth potential, our projections show the future fiscal burden will increase significantly across the board. We do not expect this burden to fall equally, though. The projected deterioration in public finances over the period 2010-2050 is particularly significant in Central and Eastern European (CEE) sovereigns, the latter also being the focus of this research. The relevant characteristics of this group of countries, in our view, a particularly rapid worsening in demographic profile, coupled with a relatively high level of existing social security coverage, although in some countries important steps have been made to contain the future budgetary pressures. However, the results of our study show the projected magnitude of the future fiscal burden will require additional measures. I. Introduction In the absence of further policy measures, we generally expect population aging will lead to increases in overall budgetary expenditures that are sensitive to demographic change, although according to our estimates the impact will differ significantly among the countries in our sample. The categories considered in this study are old-age pensions, health care, and, where data is available, long-term care for the frail and unemployment benefits. Education was not included as an age-related spending category. Although the number of pupils and students likely will decline in most countries, it is also likely that spending per student will rise to help ensure satisfactory productivity growth, given that the countries in this sample tend to be knowledge-based societies and economies. Child benefits were also excluded due to the lack of data. Although shrinking child-age cohorts could have a dampening effect on public spending through lower benefit outlays, comparable data is unavailable. Moreover, the cohort effect may be offset by more generous benefits to encourage the dual objectives of boosting labor market participation and fertility, as witnessed in several countries already. Overall, pensions remain the biggest spending item, followed by health-care and long-term care. The expected decline in unemployment benefits is typically very small and, we believe, will not produce significant relief for government spending. Based on Global Aging 2010: An Irreversible Truth, October 8, 2010 and prepared for an EBRD Conference: Pension Systems in Emerging Europe: Reform in the Age of Austerity, London, April 1, 2010. 2 Director, Standard & Poor’s Sovereign and International Public Finance Ratings. 1 Pensions (including early retirement, surviving relative, and disability pensions) are expected to remain the largest expenditure item in the future in several countries. Chart 1 shows the countries' expected increases in pension spending compared to changes in their demographic profiles, with old-age dependency ratios projected to increase. Intuitively, the more the demographic profile worsens, the higher the expected increase in age-related spending. This is, however, not always the case, as reforms can significantly cushion the expected budgetary impact of aging. For most sovereigns, the old-age dependency ratio (the number of over 65s relative to the population aged 15-64) is expected to double. In Eastern Europe, the demographic dynamics appear to be particularly affected in terms of changes in the old-age dependency ratio. However, the overall projected dynamics do not fully illustrate the variations in the level of the ratio, which for Eastern European sovereigns by 2050 is projected to be substantially higher than in other regions. In general, the strongest pressure on government budgets is expected in those sovereigns where reforms to payas-you-go (PAYG) pension systems are still pending. In Estonia and Poland, the projections of a significant fall in future pension costs may also appear to be optimistic and even possibly politically unsustainable if based on significant reductions in replacement rates, which would in turn increase the risk of poverty among the older population. In terms of health care, we expect age-related health-care spending to see the highest growth by 2050. The increase of public health-care represents in some countries a more substantial pressure on future budgetary situation, as elements related to technology and forms of service delivery are incorporated. To more completely capture the nondemographic factors, which for EU sovereigns had been the main driver of increases in health-care costs in the past, we apply the so-called technology scenario as opposed to the "AWG reference" (Aging Working Group) scenario, applied previously. (E.g. The projected health-care costs increase to GDP for the EU countries in the "AWG reference" scenario is around 1.5%, while the increase in the technology scenario is around 5.5%). Overall, this trend suggests that while there is sustained and visible ongoing progress in terms of pension system reforms, the challenge of containing future health-care costs is likely to have been underestimated and, in our opinion, needs to be addressed sooner rather than later. This challenge is compounded by the likely expansion of health-care coverage to a wider section of the population. During the same period, we project that the median cost of long-term care for the frail and elderly will also increase. Projections of long-term care dynamics are not available for emerging market sovereigns, apart for those that are part of the EU. In many CEE sovereigns, long-term care depends on informal family based networks, rather than formal assistance through social security frameworks. Still, in view of the future development of these economies, the increase in median long-term care costs for advanced countries constitutes an upside risk for their budgetary positions as demand for state-financed support will grow. Finally, potential savings on the shrinking younger end of the population pyramid are likely to be negligible, as argued above. The expected median fall in unemployment benefits in advanced economies as a consequence of tightening labor markets is projected to be only 0.1% of GDP by 2050, and we do not expect it to exceed 0.5% of GDP in any country over this period. Chart 1: Breakdown in projected increase in age-related spending in CEE and other selected sovereigns, 2010 – 2050 (in % of GDP) 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 PL EE CHN LV BG HU FR SK US JP LT WM CZ AM RO DE BRZ RU UKR SI 0 -2 Pension spending Health-care spending Long-term care Unemployment benefits Source: EPC and EC, IMF, OECD. Our spending projections for this study are based on national estimates, made available mostly through multilateral research projects conducted by the Economic Policy Council and the European Commission (2008, 2009), the OECD (2006), or the IMF (2010). When interpreting the data and the fiscal consequences simulated below, the limitations of their comparability must be kept in mind. Although these international organizations and Standard & Poor's aim to correct for undue optimism or pessimism in nationally compiled figures, the success of these harmonization attempts can only be partial (see "Standard&Poor’s: Methodological And Data Supplement" for further details). Thus, the quality of these official estimates may influence the projected fiscal and ratings trajectories. Nevertheless, we believe the methodologies underpinning the national and multilateral projections are sufficiently comparable for our analytical purposes, especially over longer timeframes. II. Results of long-term debt projections Under our base-case scenario, the government refrains from adjusting either its fiscal stance as described above or any policies governing age-related spending categories. In other words, the government takes no additional steps after 2012, which is the cut-off year for the exercise, except borrowing for any budget shortfall that may materialize. We selected 2012 as we believe that the size of current budget deficits in many countries will gradually improve and 2010 could in many cases imply a deficit bottom, which would overstate the magnitude of the long-term challenge. As age-related outlays creep upward, followed by the additional interest costs of rising national debt, total government expenditure gradually increases. Based on the assumptions of unchanged revenues and the dynamics in age-related spending above, a typical sovereign in the wider sample would likely maintain stable annual deficits until 2020. After 2020, deficits are projected to start rising gradually at first, and then, as interest payments increase due to higher debt levels (see Chart 2 and Chart 3). Chart 2: Long-term projections of CEE median general government deficit, 20102050 (in % of GDP) 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 0 -5 -10 -15 -20 -25 -30 Base case scenario "Balanced budget in 2016" scenario "No-ageing" scenario "Lower interest rate" scenario "Discriminating investors" scenario "Higher growth" scenario Source: Standard & Poor’s. Chart 3: Long-term projections of CEE median general government debt, 20102050 (in % of GDP) 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 Base case scenario "Balanced budget in 2016" scenario "No-ageing" scenario "Lower interest rate" scenario "Discriminating investors" scenario "Higher growth" scenario Source: Standard & Poor’s. Demographic projections show a particularly troubling outlook in the CEE. At present, most have relatively low fertility rates and lower, though increasing, life expectancy at birth than for example Western European sovereigns, and frequently also a negative migration balance. The age profile is typically more favourable, but the situation is expected to worsen much faster on average by the middle of the century. While the average old-age dependency ratio of the Western European sovereign is projected to double by 2050, it is expected to more than double in several CEE sovereigns (see Chart 4). Nevertheless, in some sovereigns, the dependency ratio is forecast to be closer to or even below the EU average. Nevertheless, this outlook also implies serious consequences for labour supply and economic growth unless a rise in total factor productivity compensates. The budgetary impact is a large increase in age-related spending in countries where oldage dependency ratios worsen most steeply, and in those that have not so far significantly reformed pension or healthcare systems. This is evident in the cases of countries depicted in the upper right-hand corner of the chart, like Slovenia. On the other hand, Estonia and Latvia appear to be relatively better containing the projected budgetary pressures in the long-term, despite the projected similar deterioration in demographic profile compared to other CEE peers. While the highest debt levels in 2050 (depicted by the width of the bubble) are projected in the Russia and Slovenia – mainly on the back of the unreformed social security system, the debt level in the two abovementioned Baltic sovereigns is, given the projected increase in age-related spending, relatively low. This is mainly due to the reform of the social security system and very low initial debt, especially in the case of Estonia, which combined, leads to a lower projected debt/GDP ratio. Comprehensive reform strategies to contain age-related spending are beneficial for both debt sustainability and growth — requiring lower primary balances than otherwise. In this context, several CEE sovereigns have made considerable headway. Some have introduced a three-pillar system, while others have adjusted parameters of their existing systems (see Part V on individual countries below). To fully contain budgetary risks, additional and simultaneous structural reforms, particularly in labour market policies, are required. Pension measures such as postponement of retirement and/or restrictions on early retirement require a setting of increasing employment and participation rates to absorb the labour force. Higher participation rates of older people, a particular problem in the CEE sovereigns, as well as lower unemployment, can also mitigate the challenges of ageing populations. Chart 4: Change in demographic profile and budgetary impact of population ageing in CEE sovereigns (2010 and 2050) 40 2050 2010 Slovenia 35 Age-related spending (in % of GDP) Ukraine 30 Russia Hungary Czech Republic 25 Romania 20 Slovenia Slovakia Lithuania Hungary Ukraine Bulgaria Poland 15 Czech Republic Russia Slovakia 10 Bulgaria Poland Estonia Lithuania Estonia Latvia Romania Latvia 5 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 Old-age de pe ndancy ratio (in %) Note: Bubble size depicts the size of net government debt. It varies between 2% of GDP for Estonia in 2010 and 585% of GDP in Russia in 2050. Source: Standard & Poor’s. III. Population ageing, its budgetary impact and implications for hypothetical sovereign ratings As described in the previous section, rising deficits would likely lead to downward pressure on the hypothetical sovereign ratings. This would be the case even if debt ratios remained at relatively low levels because of the sharp upward trajectory of fiscal deficits. When presented graphically for the 49 sovereigns, to get a more representative image of the rating dynamics, the collective deterioration in the hypothetical ratings becomes clearly evident (see Chart 5). The erosion in sovereign ratings would start in 2015, when hypothetical ratings on a number of highly rated sovereigns come under pressure (see "Methodological And Data Supplement" for explanations of the model). Although the downward drift is impressive by any standards, equally noteworthy is the nonlinearity of the change in theoretical ratings over time. Ratings would weaken somewhat in the second part of this decade, especially at the upper end of the rating scale, while the number of sovereigns with speculative grade ratings would fall until 2020. From that moment onward, as the full budgetary impact of population aging kicks in, the projected downward transition in sovereign ratings becomes predominant. Before then, in the real world beyond "fiscal autopilot," there could well be the risk of a mistaken sense of security taking hold that works against the changes necessary to manage the rising fiscal pressures in future years. The hypothetical ratings evolution shown here is derived by taking into account GDP per capita, general government balances, and net debt levels, and are not intended to serve as a prediction of actual outcomes. In practice, the hypothetical ratings may overstate the decline in creditworthiness. They are benchmarked against budget balances, net debt, and GDP per capita levels today, whereas it is of course possible that the medians themselves could worsen as an ever-larger number of rated sovereigns is squeezed by the costs of their aging populations. Moreover, Standard & Poor's may give more credence to mitigating credit strengths than assumed in the model. The hypothetical ratings should therefore be regarded more appropriately as an illustration of the credit dimension and profile of the demographic challenge that governments face and not as an indication of expected credit performance. Chart 5: Simulated hypothetical long-term sovereign ratings distribution (no-policy change scenario), 2010-2050 100% % of sovereigns 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 2010 AAA 2015 2020 AA 2025 2030 A 2035 BBB 2040 2045 2050 spec Source: Standard & Poor’s. Future evolution of sovereign ratings in Central and Eastern European sovereigns under the assumptions above would be similar to that of the whole sample (see Table 1), although in some cases the creditworthiness could still increase by 2040 or displays a significant volatility in this respect. The drivers behind such dynamics in the simulation of hypothetical ratings are economic growth, resulting in a higher GDP p.c. coupled by initially relatively low levels of budgetary imbalances in some cases (Duval, R. and C. de la Maisonneuve, 2009). Beyond 2040, however, the majority of sovereigns is projected to undergo a deterioration in creditworthiness with 7 sovereigns in the CEE sample ending in a speculative grade territory, while in the case of others – Poland, Estonia, and Bulgaria, no change is projected in the last decade before 2050. Table 1: Simulated hypothetical long-term sovereign ratings distribution for CEE sovereigns (no-policy change scenario), 2010-2050. Bulgaria Czech Republic Estonia Hungary Latvia Lithuania Poland Romania Russia Slovakia Slovenia Ukraine Source: Standard & Poor’s. 2010 BBB A A BBB Spec BBB A Spec BBB A AA Spec 2020 BBB A A A BBB A A BBB BBB A A Spec 2030 A A A A A A A Spec BBB A BBB Spec 2040 BBB BBB A A A BBB BBB BBB Spec BBB Spec Spec 2050 BBB Spec A BBB BBB Spec BBB Spec Spec Spec Spec Spec The "balanced budget" scenario In this scenario we assume that budgetary adjustments lead to a balanced budget in 2016 for all sovereigns. Once this is achieved, the government reverts to "fiscal autopilot" and takes no further additional action, except for borrowing to pay for the incremental agerelated (and interest) expenditures as they occur. Deficits and debt will be somewhat contained, but, in the majority of sovereigns, the containment is not sufficient to prevent unsustainable results later on. The improvement compared to the base-case scenario is particularly marked in those countries that currently have large general government imbalances, as the main assumption requires these sovereigns to take relatively larger budgetary steps by 2016. Overall, the scenario is illustrative of the power that budgetary consolidation has in offsetting the projected adverse dynamics in age-related spending. Chart 6: Simulated hypothetical long-term sovereign ratings distribution (balancedbudget scenario), 2010-2050. 100% % of sovereigns 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 2010 2015 AAA 2020 AA Source: Standard & Poor’s. 2025 2030 A 2035 BBB 2040 spec 2045 2050 Results of simulation of creditworthiness in CEE sovereigns under the assumptions above are in line with those of the overall sample (see Table 2). By balancing the budget by 2016, the situation significantly improves, as by 2040 most of the sovereigns under review have same or higher hypothetical rating as is the case currently. Nevertheless, in the last decade of the projection period, the budgetary pressure resulting from the projected increase in age-related costs is beyond the debt reducing impact of budgetary consolidation, leading to deterioration in hypothetical sovereign ratings in most cases. Nevertheless, among the 12 sovereigns covered in this exercise, only Slovenia and Ukraine end the period in the speculative grade territory. Despite this erosion in creditworthiness, the simulation displays that budgetary consolidation may be a powerful policy tool in containing the long-term challenges to public finance sustainability. Table 2: Simulated hypothetical long-term sovereign ratings distribution (balancedbudget scenario), 2010-2050 Bulgaria Czech Republic Estonia Hungary Latvia Lithuania Poland Romania Russia Slovakia Slovenia Ukraine Source: Standard & Poor’s. "No aging" scenario 2010 BBB A A BBB Spec BBB A Spec BBB A AA Spec 2020 BBB AA AA A A A A A A AA AA BBB 2030 A AA AA AA A A AA A AA AA A Spec 2040 BBB A A A A A AA A A A BBB Spec 2050 BBB BBB A A A BBB AA A BBB BBB Spec Spec In this scenario we assume that governments enact legislation to fully contain future increases in age-related spending over the projection period, illustrating the benefits of related reform measures. As such, the scenario captures in isolation the effect of the sovereigns' starting budgetary positions. Besides the impact of the current outstanding stock of government net debt on future budgetary evolution, the government balance is of particular relevance as it is assumed unchanged as of 2012 onward. Thus, while overall debt at the end of this scenario will be lower, sovereigns with relatively high expected government deficits in 2012 will see their debt burden grow faster than their peers with more balanced budget positions, despite having eliminated future increases in age-related spending. Chart 7: Simulated hypothetical long-term sovereign ratings distribution (no-aging scenario), 2010-2050. 100% % of sovereigns 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 2010 2015 2020 AAA 2025 AA 2030 A 2035 BBB 2040 2045 2050 spec Source: Standard & Poor’s. Results of simulation of creditworthiness in Central and Eastern European sovereigns under the assumptions above are in line with those of the overall sample. By balancing the budget by 2016, the situation significantly improves, as by 2040 most of the sovereigns under review have same or higher hypothetical rating as is the case currently. Nevertheless, in the last decade of the projection period, the budgetary pressure resulting from the projected increase in age-related costs is beyond the debt reducing impact of budgetary consolidation, leading to deterioration in hypothetical sovereign ratings in most cases. Nevertheless, among the 12 sovereigns covered in this exercise, only Slovenia and Ukraine end the period in the speculative grade territory. Despite this erosion in creditworthiness, the simulation displays that budgetary consolidation may be a powerful policy tool in containing the long-term challenges to public finance sustainability. Table 3: Simulated hypothetical long-term sovereign ratings distribution (no-aging scenario), 2010-2050. Bulgaria Czech Republic Estonia Hungary Latvia Lithuania Poland Romania Russia Slovakia Slovenia Ukraine Source: Standard & Poor’s. 2010 BBB A A BBB Spec BBB A Spec BBB A AA Spec 2020 BBB A A A A A A BBB BBB A AA BBB 2030 A A A AA BBB A A BBB A A A BBB 2040 A BBB A AA A A A BBB BBB BBB AA A 2050 A BBB A AA A A BBB BBB Spec BBB BBB BBB IV. Sustainability gaps and policy priorities for containing risks to long-term public finance sustainability in CEE sovereigns To better illustrate the budgetary adjustments that we believe are likely to keep public finances on sustainable footings, we analyzed what we term as sovereigns' "sustainability gap" indicators. More specifically, based on methodology published by the European Commission (2009; see "Methodological And Data Supplement" for details), the sustainability gap reveals the difference between the current structural primary balance and that which would lead to fulfilling intertemporal budgetary constraints over an infinite time horizon. In other words, it indicates the permanent budgetary adjustment required to make public finances sustainable. The gap thus represents the difference between the constant revenue ratio as a share of GDP that equates the actualized flow of revenues and expenses over an infinite horizon, and the current revenue ratio. To assess the potential impact of policy action on the future budgetary burden, we examined sustainability gaps assuming sovereigns balanced their budgets by 2016. Unsurprisingly, the results show a massive decline in sustainability gaps. The shrinkage of the gap affects sovereigns across the sample, as the initial budgetary position contributes favorably to this reduction. Thus, the narrowing of the gap is most significant in those sovereigns where this component contributes relatively more to the gap in the base-case scenario. Conversely, the balanced budget scenario affects least the sovereigns with large sustainability gaps due to the long-term change component, for example Slovenia and Ukraine. Chart 8: Sustainability gaps in CEE and other selected sovereigns, % of GDP 20 Base case scenario Balanced budget scenario 15 10 5 LV CHN HU BG PL WM LT SK CZ DE AM FR RO BRZ US SI UKR JP RU 0 Source: Standard & Poor’s. Having identified a range of potential gaps and what we believe to be their causes, we can consider the possible policy implications. Based on our framework, we believe that governments can deal with the future imbalances in three main ways: - Through structural reforms aimed at raising employment levels for older workers and raising potential economic growth; - By frontloading a sustained consolidation in budgetary positions; or - Through substantial reforms to social security and publicly-funded health care systems that go well beyond most governments' initiatives so far. Given the growing urgency of tackling the budgetary implications of population aging and the capacity of governments to influence the outcomes of policy, the latter two options appear most realistic. However, which of these two reform approaches, if any, governments decide to invest their political capital in to maximize the beneficial impact on fiscal solvency depends on the specific circumstances in each country. To assess the implied policy priorities, we relied on the scenario analyses presented above, including the base-case, "balanced budget," and "no-aging" scenarios. We estimated what percentage of the 2050 base-case net debt ratio is likely to be eradicated if the age-related spending-to-GDP ratio were to remain at 2012 levels; that is, if the radical structural measures of the "no-aging" scenario were to be implemented. At the same time, we ran the same model for the "balanced budget" scenario to assess what share of the 2050 base-case debt may disappear if the sovereign balances the structural budget by 2016. The ratio between the two suggests the balance of policy priorities. To show more clearly how the ratio indicates the permanent structural budgetary adjustment we believe is likely to ensure sustainability of public finances, we converted the obtained ratios into the sovereign-specific base-case sustainability gap indicators as reflected in Chart 9 below. Chart 9: Sovereign policy priorities – urgent budgetary consolidation or agerelated costs reform, % of GDP 10 -5 -10 Long-term policies -15 Source: Standard & Poor’s. Fiscal consolidation Policy balance JP RU PL FR US RO SK LV CHN CZ IN EE DE BG HU LT SI BRZ 0 UKR 5 V. Recent developments related to age-related spending in the CEE sovereigns 1. Bulgaria In 2009, Bulgaria's public pension bill increased sharply--by about 17%, according to estimates by Bulgaria's National Statistical Service--due, in addition to the indexation formula, to a 10% increase in the minimum pension and an approximate 40% increase in the maximum pension. Over 2009-2010, the government continued with its drive to reduce pension contributions, lowering the level of contributions to 16% from 22%. This, in turn, has led to a severe deterioration of the pension system's financial position, which, if unaddressed, could, in our opinion, lead to a much higher government debt burden throughout the projection period than we currently forecast. In reaction to this deterioration, the government that took office in 2009 has been drafting measures to reverse its growing pension deficit. Among other things, as of 2011, it has increased the pension contribution rate by 1.8 percentage points, to 17.8%. At the same time, it has come up with a pension reform extending the number of work experience years needed for full retirement benefits: If the reform is fully implemented, by 2020, men will need 40 years of work experience to retire, and women will need 37. In addition, the retirement age will rise to 63 for women and 65 for men beginning in 2020. In our view, these measures are a step in the right direction to contain future budgetary challenges, especially if accompanied by continuous budgetary consolidation. We also believe that the financial sustainability of Bulgaria's health care sector--in particular its hospitals--would improve as a result of further reform. The current health care system would benefit, in our opinion, from the downsizing of resources (in terms of the number of hospitals), streamlining of medical procedures, and elimination of incentives that lead to frequent abuses of the current health care framework. 2. Czech Republic The government is planning to introduce important changes to the pension scheme. Proposals call for a merging of the two rates of value-added tax (VAT) to offset a cut in social payroll tax and pension contributions ceilings. This would enable individuals under the age of 40 to redirect their contributions from the state-run pay-as-you-go (PAYG) scheme into individual funds (the PAYG system is financed from general revenue via a 28% social security payroll charge). Two reform options are currently being considered. Under the first, individuals would pay the bulk of the social security contribution to the PAYG scheme, with the remainder being directed to a second pillar. Under the second option, the entire social security charge would be directed to the PAYG scheme, but individuals could voluntarily contribute a further percentage of their gross wage to the second pillar, with this amount being matched by the state. A third pillar would be introduced under both options. An increase in the retirement age is also envisaged. We believe that the introduction of the individual accounts system is likely to reduce the demographic pressure on the long-term sustainability of public finances. However, given political infighting in the governing coalition, these proposed reforms may be watereddown during cabinet negotiations. 3. Hungary The current economic and budgetary outlook for Hungary presents risks about mediumto-long-term prospects for Hungary's public finances; the bulk of the fiscal adjustment has fallen on the revenue side (the most recent being the imposition of temporary "crisis taxes" on the energy, telecoms, banking, and retail sectors, which will remain in place from 2010 to 2012). The transient nature of some measures, and the absence of structural expenditure reforms, means that there is considerable uncertainty about the evolution of the fiscal balances in the medium to long term. Additional concern is the current government's proposal to roll back part of the 1997 pension reform. The 1990s reform saw the creation of mandatory private pension funds, which replaced the mandatory public pension scheme. In 2006 a fourth pillar was introduced--a pension pre-saving account that allows individuals to pay into funds that invest solely in domestic equities. These investments are eligible for the same tax breaks as the third pillar (the voluntary private pension fund). In late 2010 the current government approved changes allowing it to divert about one fifth of the Hungarian forint (Ft) 2.8 trillion in total savings in the second pillar into the state-run pay-as-you-go (PAYG) scheme. The funds will be used, in effect, to pay for current pensions and to retire state debt. These measures are envisaged to remain in effect until 2011. However, the authorities have approved additional legislation that allows individuals enrolled in private pension funds to move their private fund savings back to the PAYG scheme, in the hope of attracting up to 70% of private pension fund members (about 3 million) back to the state scheme. If this occurs, which appears likely, it would reduce public debt by the amount of the accumulated savings, helping to narrow the budget deficit and bring down public debt levels. However, while this would help reduce fiscal deficits in the short term, these measures could negatively affect public debt dynamics in the long term, not only directly through the fiscal channel but also via the real economy--the measures could deter foreign investment, reducing the productive capacity of the economy and, therefore, potential growth. 4. Latvia In our view, an aging population is likely to have important implications on economic growth and public finances. This projected increase in age-related spending of 3.7% of GDP is less than the expected 7.8-percentage-point increase for the median of the 49sovereign sample. The comparatively low increase in age-related government spending in Latvia can be explained by the existence of a second-pillar regime of mandatory individual pension accounts, which started operating in 2001. This was preceded by a reform on the first pillar pay-as-you-go pension system in 1996 and the introduction of a voluntary private pension scheme in 1998. In our view, the level of contributions to the second pillar is set to increase to 6% of personal income in 2013 from 2% in 2011-2012, although the total social contribution rate will remain unchanged at 20%. In our opinion, this is likely to limit government contingent liabilities related to pension payments. The long-term fiscal projections included in the present study do not reflect the most recent reforms to the Latvian social security system. According to the Ministry of Welfare, the special social security fund has reverted to a deficit in 2009 of around 1.5% of GDP, for the first time since 2001. We expect the fund to remain in a deficit position because of still-declining social contributions. In response, the Latvian government implemented a number of measures in 2010, including an increase in the minimum retirement age from 62 to 65 years by 2021, effective from 2016, and a pension indexation freeze up to 2013. In our view, these measures will help to contain the future demographic pressure on public finances, and will lead to a notable reduction in agerelated contingent liabilities, which we do not reflect in our estimates. 5. Poland The pension scheme was reformed in 1999 to help reduce demographic pressure on public finances. The first beneficiaries of the new system retired in 2009. It consists of two elements, both of which are mandatory and universal: The first pillar: a scaled-back PAYG notional defined contribution scheme, and The second pillar: a fully funded scheme of open pension funds--independent legal entities created and managed by private pension fund companies (OFEs), and supervised by the state. The mandatory accounts are currently funded through a 19.5% charge on salaries, of which 12.2% goes to the PAYG first pillar and 7.3% to the fully funded second pillar. In 2010, total savings under the second pillar stood at 14% of GDP. About two-thirds of these assets are invested in bonds (mainly domestic), and equities account for the rest. The 1999 reform of the pension scheme has resulted in high ongoing transition costs to the budget, as the government collects less money under the PAYG scheme and therefore must issue more debt to cover current PAYG pension obligations. In the long run, the scheme should become self-sustaining as it reduces unfunded liabilities stemming from unfavorable demographics (the old-age dependency ratio in Poland is projected to rise to 56% in 2050 from 19% in 2010). The authorities estimate that the cost of the second pillar reached a cumulative 16.5% of GDP by the end of 2010. In early March 2011, the Polish cabinet approved measures to divert 5 percentage points of the 7.3% of pension contributions that have been going to OFEs into the PAYG state-run pension scheme. The authorities estimate that this diversion of contributions will reduce the budget deficit by 0.7% of GDP in 2011 and 1.1% of GDP in 2012. The reduction in 2011 is lower than in 2012 because the adjustments have only come into effect on May 1, 2011. In our opinion, these measures represent a significant reversal of the progressive 1999 pension reform, implying that those currently employed will have to finance current pensions to a larger degree than during the past decade. We believe that the modification may have lasting effects on the accumulation of funded pensions. Between 2013 and 2017, the government is to redirect from the first toward the second pillar just over onefifth (1.2 percentage points) of the contribution rates that are scheduled to be taken away from the latter in 2011 (5 percentage points, see chart 3). The Polish pension amendments are not as drastic as those in Hungary, although the changes are similar. The Hungarian authorities have diverted over 90% of the stock of their second pillar savings (10.5% of 2010 GDP) into the first pillar PAYG scheme. That said, we believe that there is a risk that investors would not distinguish between the two countries when judging the reliability of their policies and their commitment to lasting improvement of the public accounts. In our opinion, this potential reputational association could be detrimental to Poland's funding costs, making a structural adjustment in the future more burdensome financially and politically more difficult. We consider the changes to Poland's pension system to be a symptom of the government's reluctance to engage in fundamental fiscal consolidation ahead of the general elections later this year. The pension proposals provide a short-term fix but, in our opinion, do nothing to strengthen public finances in the long term. 6. Romania Romania's rapid discretionary increase in public spending ahead of the economic and financial crisis in 2008 contributed, in our opinion, to the significant widening of the government deficit. Over 2005–2008, the Romanian government nearly doubled its spending on pensions and public wages, with growth in the latter outpacing that in private wages. Between 2007 and 2009, pension outlays rose by 3% of GDP. In 2008, Romania entered into an International Monetary Fund/EU standby arrangement concentrated on completely overhauling public spending. Among other measures, the arrangement required a substantial reform of Romania's pension system. The main elements of this comprehensive reform include: changes in the pension indexation mechanism, an increase in the tax base to include noncontributory tax segments of the public sector, an increase in the retirement age from 55 to 60 with a simultaneous extension of the length of the standard contribution period, and the elimination of special pension categories. Romania's Constitutional Court approved the reform in October 2010, but the approval was by no means simple, given the tense political environment. The present analysis factors in the full benefits of the reform in terms of pension cost reduction. According to government estimates, Romania's pension costs are set to increase by 4.8% of GDP by 2050 compared with their level in 2010, while total agerelated public expenditures will likely rise to 19.8% of GDP in 2050, from 12.3% in 2010. This increase of 7.5% of GDP is lower than the 7.8 percentage-point increase we forecast for the median of our 49-sovereign sample, reflecting the cost-saving impact of the adopted pension reform. On the basis of currently available data, we believe that the bulk of Romania's age-related spending will likely go toward pension outlays, followed by health expenditures. In our view, the increase in age-related spending will be moderate until the early 2030s, though spending will likely accelerate after this period as more people enter retirement age. In our opinion, the adopted pension reform mitigates, but does not eliminate, significant budget deterioration in the long term. If the Romanian government does not implement additional measures, we believe that the weight of general government spending-including social security--could rise significantly as age-related spending increases and as the interest bill rises in conjunction with mounting deficits and debt. 7. Russia In our opinion, the increase in age-related spending in Russia will be primarily the result of the increase in pension outlays, which are projected to increase from 9.4% of GDP in 2010 to 18.8% of GDP in 2050. At the same time, and despite moderate pension outlays compared to peers, the absolute size of individual pensions in Russia remains very low at around $100 per month, which forces pensioners to stay in the workforce and complement pension benefits with wages. The pension system in Russia has been significantly re-shaped over the past decade, developing from a pay-as-you-go system into a multi-pillar system. The first pillar is a pay-as-you-go system, with earnings-related benefits based on the contribution period. The contributions are indexed to inflation. The second-pillar regime of mandatory individual private pension accounts was introduced in 2002 and covers all contributors born in 1967 and later. The level of contributions to the second pillar is set at 6% of a payroll, while the total contribution rate to the pension system starting from 2011 accounts for 26% of a payroll, an increase from 20% in 2010. Despite the implementation of structural reforms over past years, the pension system in Russia continues to suffer from some structural weaknesses, such as relatively generous eligibility rules and low effective retirement rates. Currently, the legal retirement age is set at 60 years for men and 55 years for women, while the average life expectancy at birth for men is 62 years. However, early retirement exemptions have pushed the average retirement age below the legal retirement rate, which adds to financial pressures on the system. The additional problem is that most of the workers involved in the second-pillar system did not exercise their right to choose a private asset-manager to manage their individual pension accounts. By law, those accounts are managed by Vnesheconombank, which has been unsuccessful in providing adequate real returns to contributors, which is likely to result in low pension replacement rates in the future. The low returns are explained by the limited choice of financial instruments in which VEB has been permitted to invest. This should be partially resolved with the new law implemented in 2009, which widens VEB's investment alternatives. In our opinion, however, still-high inflation rates limit the possibility to generate moderate real returns without taking significant risks. 8. Slovenia Despite the fact that Slovenia's budgetary challenges related to its aging population have been well identified, the authorities have, in our opinion, been slow to deal with them in an effective manner. Furthermore, in 2005, the previous government actually reversed one of the earlier reform achievements by establishing a pension indexation mechanism based solely on wage growth, which has since been adding pressure to public finances. The government's policy regarding pension outlays is mainly two-pronged: · First, against a background of increasing pressure on public finances, it aims to limit the indexation of pension benefits in 2011 to a quarter of the prescribed increase. · Second, the government proposed a pension reform, which includes a number of parametric and structural changes, such as a change in the indexation formula, an extension of the retirement age to 65, an extension of the base period for calculating pension benefits, and a toughening of the conditions for early retirement. We believe that advances in these areas are significantly influenced by a difficult and particular political environment. Namely, the consecutive governing coalitions have included the DESUS political party—representing pensioners' interests--which is, together with trade unions opposing the proposed changes to the pension indexation and pension system reform. In this context, the government's resolve for a breakthrough in the pension system reform and the coalition's cohesion was tested in the national referendum on the pension reform in June 2011. The defeat of the government’s proposal indicates failing support for the minority center-left government, possibly complicating its prospects to meet budgetary targets through consolidation, while at the same time raising the probability of a no confidence vote or early elections. We believe the defeat is likely to lead to a stalemate in using changes to the pension system to address the budgetary challenges arising from Slovenia's aging population. It is likely that a new attempt at reforming the pension system may not take place before early 2013. This is due to a law that imposes a one-year moratorium on any subsequent, similar legislation to a referendum. Finally, in terms of the interaction of demographic and political dynamics, Slovenia presents a very interesting case from a broader geographical perspective. The effective opposition to the pension system reform is mainly being channeled through trade unions and a single political party, whose explicit aim is to represent the interests of pensioners. With the acceleration of the population's aging, this segment of the electorate will grow further--and not only in Slovenia--and could act as an important constraint on social system reform efforts in the future. 9. Ukraine In our view, the rise in age-related spending in Ukraine will be mostly the result of the increase in pension outlays. Despite the formal implementation of a three pillar pension system, Ukraine's pension regime continues to be a de facto one-pillar pay-as-you-go system. The second-pillar regime of mandatory individual pension accounts is not yet in operation, and the coverage of voluntary private pension schemes--the so-called third pillar--accounted for only 0.1% of GDP at the end of September 2010. In our opinion, the pay-as-you-go system in Ukraine suffers from some serious structural weaknesses, such as the low retirement age (which is set to increase as of 2014), a low minimum contribution period, and generous early retirement provisions. In addition, we believe there is a systemic compliance problem on the revenue side as a lot of employers prefer to pay 'gray' salaries to avoid paying social contribution tax. As a result, although the size of individual pensions is moderately low and the social contribution rate in Ukraine is high at 35.2%, the deficit of the pension fund continues to widen. The Ukrainian government is currently considering a pension reform as part of the Stand-By Arrangement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The reform includes a rise in the retirement age for women to 60 through biannual increases, cuts in the maximum pension size, and an increase in the qualifying period for a full pension. The reform also aims to implement the missing second-pillar regime of mandatory individual pension accounts. However, as a prerequisite to the implementation of the second-pillar, the pension fund must be in balance. In our view, this is unlikely to happen over the coming years. We think it likely that the reform will be partially diluted when passed through parliament, in response to public hostility to the intended changes. Savings in relation to pension liability could be achieved through the de-indexation of pension levels; however, we consider de-indexation to be unlikely at present. Note that the potential positive impact of the IMF-mandated pension reforms on public finances is not reflected in our projections. Nevertheless, even if the reform were to be implemented, we believe the government would have to take additional measures to put long-term public finances on a sustainable path and comply with its long-term contingent liabilities coming from the pension system. These measures would include the introduction of a working mandatory second-pillar system. The window of opportunities for the implementation of such measures, however, is now closing. IV. References Economic Policy Committee and European Commission (2008), "The 2009 Ageing Report: Underlying Assumptions and Projection Methodologies," European Economy, No. 7/2008. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication13782_en.pdf Economic Policy Committee and European Commission (2009), "The 2009 Ageing Report: Economic And Budgetary Projections For The EU-27 Member States (20082060)," European Economy, No. 2/2009. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication14992_en.pdf European Commission (2009), "Sustainability Report 2009," European Economy, No.9/2009. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication15998_en.pdf Duval, R. and C. de la Maisonneuve (2009), "Long-Run GDP Growth Framework And Scenarios For The World Economy", OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 663, OECD Publishing, Doi: 10.1787/227205684023. http://www.oecdilibrary.org/economics/long-run-gdp-growth-framework-and-scenarios-for-the-worldeconomy_227205684023 IMF (2010), "From Stimulus To Consolidation: Revenue And Expenditure Policies In Advanced And Emerging Economies," IMF Policy Paper. www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2010/043010a.pdf OECD (2006), "Projecting OECD Health And Long-Term Care Expenditures: What Are the Main Drivers?," OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 477, OECD Publishing, doi: 10.1787/736341548748. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/projecting-oecd-health-and-long-term-care expenditures_736341548748 Standard & Poor’s (2010): Global Aging 2010: An Irreversible Truth, October 8, 2010. Standard & Poor’s (2010): Global Aging 2010: An Irreversible Truth--Methodological And Data Supplement, October 8, 2010. Standard & Poor’s (2010, 2011): Global Aging 2010: Individual Country Reports.