achieving justice: the case for legislative reform

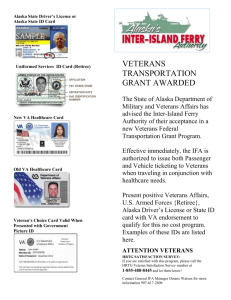

advertisement