The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins

advertisement

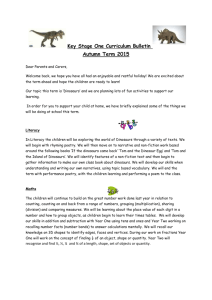

The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins By Barbara Kerley 1. Horse-drawn carriages clattered down the streets of London in 1853. 2. Gentlemen tipped their hats to ladies 1. _______ passing by. 3. Children ducked and dodged on their way to 2. _______ school. 3. _______ 4. But Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins had no time to be out and about. 5. Waterhouse, as he liked to call himself, 4. _______ hurried toward his workshop in a park south of town. 6. He 5. _______ was expecting some very important visitors. 7. He didn’t 6. _______ want to be late. 7. _______ 8. As he neared his workshop, Waterhouse thought of 1 the hours he’d spent outside as a boy. 9. Like many artists, 8. _______ he had grown up sketching the world around him. 10. By the 9. _______ time he was a young man, he’d found his true passion: animals. 10. ______ 11. He loved to draw and paint them. 12. But what he really 11. ______ loved was sculpting models of them. 13. Through his care and 12. ______ hard work, they seemed to come to life. 13. ______ 14. Now Waterhouse was busy with a most exciting project: He was building dinosaurs! 15. His creations would 14. ______ prowl the grounds of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s new art and science museum, the Crystal Palace. 15. ______ 16. Even though the English had found the first known dinosaur fossil many years before -- and the bones of more dinosaurs had been unearthed in England since 2 then—in 1853, most people had no idea what a dinosaur looked like. 16. ______ 17. Scientist weren’t sure either, for the only fossils were some bits and pieces—a tooth here, a bone there. 18. But 17. ______ they thought that if they studied a fossil and compared it to a living animal, they could fill in the blanks. 18. ______ 19. And so, with the help of scientist Richard Owen, who checked every muscle, bone, and spike, that’s exactly what Waterhouse was doing. 20. He wanted to create such 19. ______ perfect models that anyone—a crowd of curious children, England’s leading scientists, even the Queen herself!—could gaze at his dinosaurs and see into the past. 21. Waterhouse threw open the doors to his workshop. 20. ______ 21. ______ 3 22. Nervously, he tidied up here and there. 23. His assistants 22. ______ came, then Richard Owen. 23. ______ 24. At last, the visitors arrived: Queen Victoria and Prince Albert! 25. The Queen’s eyes grew wide in surprise. 24. ______ 25. ______ 26. Waterhouse’s creatures were extraordinary! 27. How on 26. ______ earth had he made them? 27. ______ 28. He was happy to explain: The iguanodon, for instance, had teeth that were quite similar to the teeth of an iguana. 29. The iguanodon, then, must surely have looked like 28. ______ a giant iguana. 30. Waterhouse pointed out that the few 29. ______ iguanodon bones helped determine the model’s size and proportion. 31. And another bone—almost a spike—most 30. ______ 4 likely sat on the nose, like a rhino’s horn. 32. Just so for the megalosaurus. 33. Start with its 31. ______ 32. ______ jawbone. 34. Compare it to the anatomy of a lizard. 35. Fill 33. ______ 34. ______ in the blanks. 36. And voila! 37. A dinosaur more than forty 35. ______ 36. ______ feet long. 37. ______ 38. Waterhouse was also making ancient reptiles and amphibians. 39. While Richard Owen could imagine their 38. ______ shapes, it took an artist to bring the animals to life. 39. ______ 40. Designing the creatures was only the first step. 41. There was still the monumental task of building them. 40. ______ 41. ______ 42. Waterhouse showed his guests the small models he’d made, correct in every detail, from scales on the nose to nails on the toes. 43. With the help of his assistants, he had 42. ______ 5 formed the life-size clay figures and created the molds from them. 44. Then he erected iron skeletons, built brick 43. ______ foundations, and covered the whole thing with cement casts from the dinosaur-shaped molds. 45. Designing the creatures was only the first step. 46. There was still the monumental task of building them. 44. ______ 45. ______ 46. ______ 47. Waterhouse showed his guests the small models he’d made, correct in every detail, from scales on the nose to nails on the toes. 48. With the help of his assistants, he had 47. ______ formed the life-size clay figures and created the molds from them. 49. Then he erected iron skeletons, built brick 48. ______ foundations, and covered the whole thing with cement casts from the dinosaur-shaped molds. 49. ______ 6 50. “It is no less,” Waterhouse concluded, “than building a house upon four columns.” 50. ______ 51. In the weeks to follow, Waterhouse basked in the glow of the Queen’s approval. 52. But he would soon face a 51. ______ much tougher set of critics: England’s leading scientists. 52. ______ 53. Waterhouse wanted to be accepted into this circle of eminent men. 54. What would they think of his dinosaurs? 55. There was only one way to find out. 53. ______ 54. ______ 55. ______ 56. Waterhouse would show them. 57. But why not do it with 56. ______ a little style? 58. A dinner party. 59. On New Year’s Eve, no less. 57. ______ 58. ______ 59. ______ 60. And not just any dinner party. 61. Waterhouse would stage 60. ______ an event that no one would ever forget! 61. ______ 7 62. He sketched twenty-one invitations to the top scientists and supporters of the day, the words inscribed on a drawing of a pterodactyl wing. 63. He pored over menus with 62. ______ the caterer. 64. The iguanodon mold was hauled outside. 65. A platform was built. 66. A tent erected. 63. ______ 64. ______ 65. ______ 66. ______ 67. As the hour drew near, the table was elegantly set, and names of famous scientists—the fathers of paleontology—were strung above the tent walls. 68. All was 67. ______ ready. 68. ______ 69. With great anticipation, Waterhouse dressed for the occasion in his finest attire. 70. He was ready to reveal his 69. ______ masterpiece! 70. ______ 8 71. When the guests arrived, they gasped with delight! 71. ______ 72. Waterhouse smiled as he signaled for dinner to begin. 73. With solemn formality, the footmen served course 72. ______ after course from silver platters. 74. Up and down the steps of 73. ______ the platform they carried the lavish feast: rabbit soup, fish, ham, and even pigeon pie. 75. For dessert, there were nuts, 74. ______ pastries, pudding, and plums. 76. Two footmen stayed busy 75. ______ simply pouring the wines. 76. ______ 77. For eight hours, the men rang in the New Year. 77. ______ 78. They laughed and shouted. 79. They made speech after 78. ______ speech, toasting Waterhouse Hawkins. 80. All the guests 79. ______ agreed: The iguanodon was a marvelous success. 81. By 80. ______ midnight they were belting out a song created especially for 9 the occasion: THE JOLLY OLD BEAST IS NOT DECEASED THERE’S LIFE IN HIM AGAIN! 81. ______ 82. The next months passed by in concrete, stone, and iron, as Waterhouse put the finishing touches on his dinosaurs. 82. ______ 83. Inside the iguanodon’s lower jaw he signed the work: B. HAWKIND, BUILDER, 1854. 84. The models were now 83. ______ ready for the grand opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham Park. 84. ______ 85. Forty thousand spectators attended the regal ceremony. 86. In the sun-filled center court, Waterhouse 85. ______ mingled with scientists and foreign dignitaries. 87. At last, 86. ______ the Queen arrived! 88. The crowd cheered, “Hurrah!” 87. ______ 88. ______ 10 89. Cannons boomed, music swelled, and a choir of one thousand voices sang. 90. Waterhouse bowed before the 89. ______ Queen. 91. Then she and Prince Albert invited the spectators 90. ______ to enjoy the amazing sights. 91. ______ 92. First two, then ten, then a dozen more…Gasped! Shrieked! Laughed and cried: So this was a dinosaur! 93. Waterhouse was thrilled. 94. For in addition to being an artist, he also saw himself as a teacher. 95. He was 92. ______ 93. ______ 94. ______ convinced that the best way for people to learn about something was to see it. 96. With this love of art and teaching, 95. ______ he knew he could do more. 97. Educational posters. 96. ______ 97. ______ 98. Small models anyone could buy. 99. Lectures. 98. ______ 99. ______ 100. Books to illustrate. 101. For the next fourteen years, 100. _____ 11 Waterhouse did it all. 102. News of his success had reached America. 101. _____ 102. _____ 103. In 1868, Waterhouse traveled to New York City, filling a lecture hall for talks about dinosaurs, evolution, even dragons. 104. As he spoke, he sketched such marvelous 103. _____ illustrations that the audience burst into applause. 104. _____ 105. And then, Waterhouse received a delightful surprise: a letter from the head of Central Park, inviting him to build American dinosaurs! 106. His models would inhabit a 105. _____ museum planned for the park’s southwest corner. 106. _____ 107. Waterhouse was excited. 108. America’s first two 107. _____ dinosaurs, Hadrosaurus and Laelaps, had only recently been discovered. 109. Here was his chance to bring these dinosaurs 108. _____ 12 to life for all to see. 110. Waterhouse set right to work. 111. He spent the 109. _____ 110. _____ next six months traveling to American museums to learn about American dinosaurs. 112. Again, he built something no one 111. _____ had ever seen before: the first model of a complete dinosaur skeleton. 112. _____ 113. He presented the Hadrosaurus to The Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, where it was a welcomed with great enthusiasm. 113. _____ 114. Now Waterhouse was ready to build his dinosaurs. 114. _____ 115. He returned to New York City to the workshop built for him in Central Park. 116. He hired an assistant, and the real 115. _____ work began. 117. Small models. 118. Life-size clay figures. 116. _____ 117. _____ 118. _____ 13 119. Iron skeletons. 120. Dinosaurs. 119. _____ 120. _____ 121. While he and his assistant toiled inside, workmen outside began building the museum. 122. Like the Crystal 121. _____ Palace, the Paleozoic Museum would be an enormous structure of iron and glass with a beautiful arched ceiling. 123. Day after day, workmen dug the foundation. 122. _____ 123. _____ 124. Then disaster struck. 125. William “Boss” Tweed, 124. _____ a corrupt politician who controlled much of New York City, said the museum was a waste of money. 126. At six tall and 125. _____ three hundred pounds, Boss Tweed was a big man, with an even bigger thirst for power. 127. He reorganized the Parks 126. _____ Department and put his own men in charge. 128. Waterhouse 127. _____ watched in dismay as work on the museum was stopped. 128. _____ 14 129. He began looking for a new home for his dinosaurs. 129. _____ 130. But he was frustrated that a thieving scoundrel could thwart almost two years of work. 130. _____ 131. In March of 1871, Waterhouse gave a speech at the New York Lyceum of Natural History. 132. He stressed the 131. _____ importance of science and art, then shared the troubles he’d had with the Boss. 132. _____ 133. “I trust, however,” Waterhouse concluded, “that in time the good sense of the people will awaken and that they will realize the vast importance of my work.” 134. The audience agreed. 135. One man called the 133. _____ 134. _____ Boss greedy. 136. Another said that the Boss was an “Enemy 135. _____ of Mankind.” 137. The New York Times printed it all. 136. _____ 137. _____ 15 138. Waterhouse carried on with his work, but on May 3, his dream was shattered. 138. _____ 139. Vandals broke into his workshop. 140. Wielding 139. _____ sledgehammers, they smashed the dinosaurs. 141. Then they 140. _____ carted the pieces outside and buried them in the park. 141. _____ 142. Waterhouse arrived to find chaos: chunks of rubble, mangled wire, plaster shards, and dust. 143. He 142. _____ simply couldn’t believe it. 143. _____ 144. Waterhouse stumbled outside, only to find mounds of dirt and dinosaur rubble. 145. Two years of his life, utterly 144. _____ ruined. 146. This could only be the work of Boss Tweed. 145. _____ 146. _____ 147. The more Waterhouse thought about, the angrier he 16 became. 148. He protested to the Parks Department. 149. The 147. _____ 148. _____ situation was outrageous! 150. Criminal! 151. Surely 149. _____ 150. _____ something could be done! 151. _____ 152. But Waterhouse was bluntly told not to waste his time with “dead animals” when there were so many living ones around. 153. Waterhouse staggered away. 154. His dinosaurs were broken, and so was his spirit. 152. _____ 153. _____ 154. _____ 155. But in spite of the Boss, Waterhouse would give America her dinosaurs. 155. _____ 156. He left New York to create towering hadrosaur skeletons for Princeton University in New Jersey and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. 157. He stayed 156. _____ 17 on at Princeton, yet again creating something that no one had ever seen before: the first series of paintings showing the development of life on Earth, including his beloved dinosaurs. 157. _____ 158. Waterhouse was now seventy-one years old. 159. It was time to go home. 158. _____ 159. _____ 160. Waterhouse returned to London and exciting news: Thirty iguanodon skeletons had been discovered in a coal mine in Belgium. 161. It now appeared that 160. _____ Waterhouse’s beloved iguanodon might have walked upright, on its hind feet. 162. And the spike on the nose—like a 161. _____ rhino’s horn—might actually be a thumb. Imagine that! 162. _____ 163. Waterhouse settled back into his cottage, Fossil Villa, near the Crystal Palace. 164. And on pleasant 163. _____ 18 afternoons, as he walked to the park and his marvelous creations, he wondered: What other surprises would scientists dig up as they searched the world for dinosaurs? 164. _____ 165. Just as he had hoped, his models were the start of something wonderful: the world’s first encounter with these ancient animals. 165. _____ 166. People still come to the Crystal Palace Park in England to see the dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins. 166. _____ 167. And while his American dinosaurs no longer stand, somewhere, buried in Central Park, pieces of his dinosaurs remain. 167. _____ 19