From Wired Magazine Nov 2000: The Truth, The Whole Truth, and

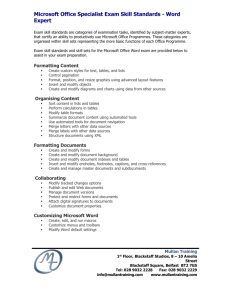

advertisement