final thesis

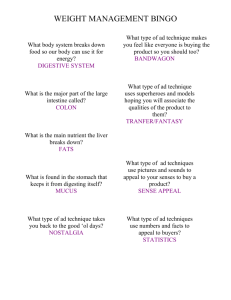

advertisement