Bibliography on R&D Collaborations

advertisement

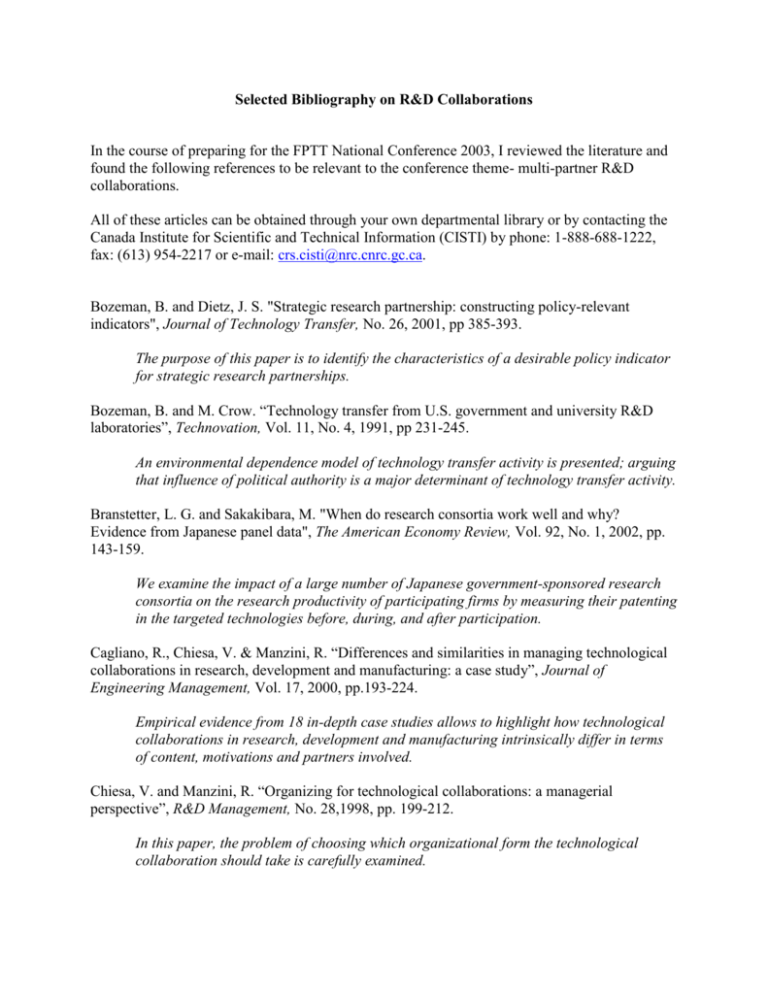

Selected Bibliography on R&D Collaborations In the course of preparing for the FPTT National Conference 2003, I reviewed the literature and found the following references to be relevant to the conference theme- multi-partner R&D collaborations. All of these articles can be obtained through your own departmental library or by contacting the Canada Institute for Scientific and Technical Information (CISTI) by phone: 1-888-688-1222, fax: (613) 954-2217 or e-mail: crs.cisti@nrc.cnrc.gc.ca. Bozeman, B. and Dietz, J. S. "Strategic research partnership: constructing policy-relevant indicators", Journal of Technology Transfer, No. 26, 2001, pp 385-393. The purpose of this paper is to identify the characteristics of a desirable policy indicator for strategic research partnerships. Bozeman, B. and M. Crow. “Technology transfer from U.S. government and university R&D laboratories”, Technovation, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1991, pp 231-245. An environmental dependence model of technology transfer activity is presented; arguing that influence of political authority is a major determinant of technology transfer activity. Branstetter, L. G. and Sakakibara, M. "When do research consortia work well and why? Evidence from Japanese panel data", The American Economy Review, Vol. 92, No. 1, 2002, pp. 143-159. We examine the impact of a large number of Japanese government-sponsored research consortia on the research productivity of participating firms by measuring their patenting in the targeted technologies before, during, and after participation. Cagliano, R., Chiesa, V. & Manzini, R. “Differences and similarities in managing technological collaborations in research, development and manufacturing: a case study”, Journal of Engineering Management, Vol. 17, 2000, pp.193-224. Empirical evidence from 18 in-depth case studies allows to highlight how technological collaborations in research, development and manufacturing intrinsically differ in terms of content, motivations and partners involved. Chiesa, V. and Manzini, R. “Organizing for technological collaborations: a managerial perspective”, R&D Management, No. 28,1998, pp. 199-212. In this paper, the problem of choosing which organizational form the technological collaboration should take is carefully examined. Cyert, R.M. and Goodman, P. S. “Creating effective university-industry alliances: an organizational learning Perspective”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 25, No. 4, 1997, pp. 45-57. A new way of thinking about research partnerships can ease the conflicts inherent in these relationships and produce long-term benefits for everyone. Dodgson, M. “Technological collaboration: problems and pitfalls”, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1992, pp 83-88. Analysts have struggled with the question of what collaboration means for public policy, for the innovation process and, indeed, what it means for our understanding of what firms actually are. Others have posed the question of how they can help firms profitably use collaboration as a strategic tool. Dodgson, M. “The strategic management of R&D collaboration”, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, Vol. 4, No. 3, 1992, pp. 227-244. Because of the high management cost s of collaboration, the length of time needed to build effective communications paths between different organizations, and the specific technological nature of these forms of inter-firm linkage, R&D collaboration should be a strategic concern. Dreyfuss, R. C. “Collaborative research: conflicts on authorship, ownership, and accountability”, Vanderbilt Law Review, Vol. 53, 2000, p. 1161. This article proposes a series of legal rules that utilize both intellectual property laws’ concepts of authorship and inventorship and Coasian ideas of transactional freedom. These rules provide a benchmark for collaborative parties, thereby assisting them in identifying issues and structuring workable arrangements. Elton, J. J., Shah B. R. and Voyzey, J. N. “Intellectual property: partnering for profit”, The McKinsey Quarterly, No. 4., 2002, pp. 60-67. Companies could earn up to 10 percent of their operating income from the sale of patents and proprietary processes. But how? Etzkowitz, H. “The entrepreneurial university”, Technology Access Report, 1998, pp. 8-10. An entrepreneurial academic dynamic is based on a pubic/private partnership that connects the patent system to the intellectual output of the university research group, on the one hand, and integrates the research group into an organizational network of transfer offices, incubator facilities and venture capital firms, on the other. The cycle is completed by support received directly from government R&D funds and production contracts. Etzkowitz, H. and Leydesdorff, L. “The dynamics of innovation: from national systems and "mode 2" to a triple helix of university-industry-government relations”, Research Policy, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2000, pp.109-123. The Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations is compared with alternative models for explaining the current research system in its social contexts. Finn, T. M. and McCamey, D. A. “P&G’s guide to successful partnerships”, Pharmaceutical Executive, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2002, pp. 54-60. “You never listen to me” … Those comments sound like complaints from people in a troubled marriage, but the partners in this relationship are companies, and it’s their corporate alliance that is failing. With strategic alliances becoming the US pharma industry’s “mode of operation.” Geisler, E. and Rubenstein, A.H. “University-industry relationships: a review of major issues”, in A.N.Link and G.Tassey (Editors), “Cooperative research and development: the industryuniversity-government relationship”, Kluwer Academic Press, Boston 1989, pp.43-64. In review of current literature, we have identified six major issues or categories of key factors impinging upon the following questions: Why do universities and industry cooperate? What are the more effective mechanisms for such cooperation? What are the main barriers to such cooperation? Golota, M. “Inventorship is different from authorship”, University Intellectual Property Review, Spring 1993, Vol. 1 (2). The academic culture which led to the old cliché "publish or perish" is still prevalent in many universities. One aspect of the "publish or perish" mentality is the practice of awarding recognition to all members of a research project team. Papers and articles disclosing the results of university sponsored research projects often give authorship credit to everyone involved with the project. In many cases, this mentality of giving credit to all involved in a project carries over to U.S. and foreign patents. However, inventorship is not analogous to authorship. The two are not interchangeable. The following discussion will focus on the avoidance of incorrect inventorship determinations which could jeopardize the validity of issued patents and hamper the ability to patent a faculty member's subsequent developments. Graff, G., Heiman A. and Zilberman D. “University research and offices of technology transfer”, California Management Review, Vol. 45, No. 4, 2002, pp. 88-115. Offices of technology transfer are a recent institutional innovation created by universities to provide a new marketing channel and to improve this flow of trade between university research and industry. OTTs are uniquely charged with coordinating the legal protection of university research results in the form of intellectual property in order to make them more transactable and valuable in industry. Hagedoorn, J. “Inter-firm R&D partnership: an overview of major trends and patterns since 1960”, Research Policy Vol. 31, 2002, pp.477-491. This paper presents an initial analysis of some major trends and patterns in inter-firm R&D partnering since the early 1960s. The paper focuses on collaboration between independent companies through formal agreements, such as contractual agreements and joint ventures. Hagedoorn, J., Link, A. N. and Vonortas, N. S. “Research partnerships”, Research Policy, Vol. 29, 2000, pp.567-586. This paper synthesizes the academic, professional, and policy litrature on research partnership with an eye towardstechnology policy. Hall, B. H., Link, A. N. and Scott, J. T. “Barriers inhibiting industry from partnering with universities: evidence from the advanced technology program", Journal of Technology Transfer, No. 26, 2001, pp 87-98. A small sample of 38 Advanced Technology Projects funded between 1993 and 1996 are surveyed to explore the reasons for industry non-participation, or, in the cases where they did participate, whether the partnerships encountered any difficulties from their participation. Ham, R. M. and Mowery, D. C. “Improving the effectiveness of public-private R&D collaboration: case studies at US weapons laboratory”, Research Policy, No. 26, 1998, pp. 661-675. This paper presents the results of the first systematic case studies of Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs) between private firms and one of the large US weapons laboratories, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL. These cases cover a diverse array of technologies, and include firms with very different characteristics. Harding, R. “Competition and collaboration in German technology transfer”, European Management Journal, Vol. 20, No. 5, 2002, pp.470-485. What is remarkable about the German system is its capacity to anticipate and pre-empt changes and to adapt appropriately when the need arises. The material presented here suggests no reason to doubt that this trend will continue. Howells, J. and Nedeva M. “The international dimension to industry-academic links”, International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 25, Nos. 1/2, 2003, pp.5-17. This paper reviews the growth in industry-academic relations and the widening international dimension of higher education research systems. It addresses two questions: the function of the university in today’s knowledge based economy and the relationship of universities and other higher education colleges to their domestic base. Jap, S. D. "Pie-sharing in complex collaboration contexts", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 38, No. 1, 2001, pp 86-99. Sharing principles can have a positive or negative effect on the relationship depending on the type of sharing principle used, and the characteristics of the resources and organizations. In particular, sharing processes should be responsive to the goals of the collaboration. Katila, R. and Mang, P. “Exploiting technological opportunities: the timing of collaborations”, Research Policy, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2003, pp 317-332. High-technology companies that discover new technological opportunities face two critical decisions: whether and when to collaborate in exploiting these opportunities. Kotnour, T. and Buckingham, G. “University partnership help aerospace firms”, Reasearch Technology Management, Vol. 44, No. 3, 2001, pp.5-7. Based on a study on partnerships between Florida’s universities and aerospace industries, “university and technology companies need to do a better job communicating their perspective needs and the services they can provide each other.” Link, A.N., Paton, D. and Siegel, D.S. “An analysis of policy initiatives to promote strategic research partnerships”, Research Policy, Vol. 31, No. 8, 2002, pp. 1459-1466. “A major change in the US National Innovation System has been the rapid increase in Strategic Research Partnerships (SRPs) involving American firms, universities, nonprofit organizations, federal research laboratories, and public agencies.” This paper examines the antecedents and consequences of centerpiece legislation designed to stimulate the formation of SRPs. Mowery, D. C. “Collaborative R&D: how effective is it?”, Issues in Science and Technology, Vol. 15, 1998, pp.37-44. A single-minded industry "vision" can conserve resources, but it may be ill advised in the earliest stages of development. Newberg, J. A. and Dunn, R. L. “Keeping secrets in the campus lab: law, values and rules of engagement for industry-university R&D partnership”, American Business Law Journal, Vol. 39, 2002, pp.187-240. Referenced in a US Supreme court case, this paper examines “rules and organizational forms for structuring industry-university partnerships, with a focus on the problem of protecting confidential information in the context of industry research collaboration (IURC)”. Norman, P. "Are your secrets safe? Knowledge protection in strategic alliances", Business Horizons, Vol. 44, No. 6, 2001, pp. 51-60. Certain structures and processes can be used to prevent partners from observing, understanding, acquiring, or imitating a firm’s critical knowledge and capabilities. Parry, R. and Fitchett, E. “Collaborating to create IP? Identify your aims first”, Managing Intellectual Property, No. 96, 2000. Collaborations can be the most effective way to exploit new technologies. Santoro, M. D. and Betts, S. C. "Making industry-university partnerships work", ResearchTechnology Management, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2002, pp 42-46. A study of relationships between industrial firms and university research centers shows how to form partnerships that benefit both parties. Santoro, M. D. and Gopalakrishnan, S. “Relationship dynamics between university research centers and industrial firms: their impact on technology transfer activities”, Journal of Technology Transfer, Vol. 26, Nos. 1/2, 2001, pp.163-171. Data collected from 189 industrial firms working with 21 research centers affiliated with prominent research-oriented universities in the US “showed that trust, geographic proximity, and flexible university policies for IPR, patents, and licenses were strongly associated with greater technology transfer activities.” Smith, R. and Ahmed, M. “Dance with your collaborators”, Research Technology Management, Vol. 43, No. 5, 2000, pp.58-60. Based on our studies of 13 Japanese and Canadian firms and their partners, it seems clear that when dissimilar organizations work together, they need concrete collaboration skills to guide their actions. Starbuck, E. “Optimizing university research collaborations”, Research Technology Management, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2001, pp.40-44. Collaborative effectively means doing the right thing, doing it well, rewarding success, and feeding back knowledge from the experience. Stone, A. “Allocation of ownership of inventions in joint development agreements – the Australian perspective”, Les Nouvelles, March 2003, pp. 23-26. Collaborations and joint developments offer many benefits to their participants, in particular, the ability to access technology and IP developed by the other participants. However, it is important to consider how any resulting inventions or improvements to technology will be owned. Thursby, J. G., Jensen, R., and Thursby, M. C. “Objectives, characteristics and outcomes of university licensing: a survey of major U.S. universities”, No. 26, 2001, pp.59-72. Based a survey of licensing at 62 research universities, “patent applications grow oneto-one with disclosures, while sponsored research grows similarly with licenses executed. Royalties are typically larger the higher the quality of the faculty and the higher the fraction of licenses that are executed at latter stages of development.” Williams, K. “Creating partnerships with power”, Environmental Design and Construction, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2002, pp 42-45. A great deal can be gained from successful university/industry partnerships, but a number of changes are needed in the way such partnerships are approached and maintained.