Imperialism Primary Docs

advertisement

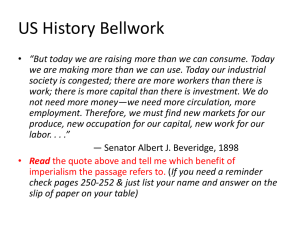

Name ____________________________________________ Date ________ Period _____ PRIMARY DOCUMENTS: IMPERIALISM Directions: Read the three documents related to imperialism and answer the questions on a separate sheet of paper. Stanley Searches for Livingstone in Africa – Henry M. Stanley (1871) 1. Traveling through Africa (often called “going on safari”) was often seen as a big adventure by Europeans. As Stanley’s journey was coming to an end and he marched toward the village in which he believed he would find Dr. Livingstone how did he seem to feel? Explain. 2. Why do you suppose Stanley made such a dramatic entrance as he approached the village? 3. Henry Stanley’s entire trip was paid for by the New York Herald. Why do you think the New York Herald was willing to fund Stanley’s trip? The White Man’s Burden – Rudyard Kipling (1899) 4. How does Kipling describe the people of the Philippines in the first stanza? 5. In the third stanza Kipling writes “Watch sloth and heathen folly bring all your hopes to nought.” What does this mean? How do you think the White Man’s Burden would remedy this situation? 6. The forth stanza outlines some of the difficulties that Europeans face when imperializing a nation; none of these problems were unknown to Europeans. How does this emphasize the importance of the White Man’s Burden in the eyes of Europeans? 7. Some people argue that Kipling and other Europeans during the Age of Imperialism believed that the people being colonized recognized that there were in fact benefits to colonization. How do the final stanzas of Kipling’s poem outline the benefits of colonization for the colonized? The Black Man’s Burden – Hubert Harrison (1920) 8. In his first stanza, what is Harrison describing? 9. In his second stanza, what institutions does Harrison say control the victims of colonization? 10. Later in the poem, after graphically describing the brutality of imperialism, Harrison refers to the “fraud of freedom” perpetrated by the imperialists to “cloak [their] greediness”. What does he mean? Comparing the Two Poems 11. How does the structure of the second poem reflect the first? 12. In “The White Man’s Burden” who does Kipling say will benefit from imperialism? How does that differ from Harrison’s “The Black Man’s Burden”? Who do you think is more accurate? 13. Choose a stanza from each poem to contrast creatively. You must use the same stanza from each poem in your product (this means that if you use the first stanza from Kipling you must also use the first stanza from Harrison) in order to maintain thematic uniformity. You can produce a drawing, a written analysis, rewrite a song…really, anything you would like…but make sure to clearly show the correlations and distinctions between the two poems. STANLEY SEARCHES FOR LIVINGSTONE IN AFRICA – HENRY M. STANLEY (1871) OVERVIEW One of the great newspaper stories of the late 1800s revolved around the disappearance of Scottish missionary David Livingstone while he was exploring Central Africa. Although much of Africa was still uncharted territory, the New York Herald sent a reporter, Henry Morton Stanley, to find Livingstone. Here is Stanley’s account of the final hours of his quest in 1871, including his now famous greeting, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" A couple of hours brought us to the base of a hill, from the top of which the Kirangozi said we could obtain a view of the great Tanganyika Lake. Heedless of a rough path or of the toilsome steep, spurred onward by the cheery promise, the ascent was performed in a short time. I was pleased at the sight; and, as we descended, it opened more and more into view until it was revealed at last as a grand inland sea, bounded westward by an appalling and black-blue range of mountains, and stretching north and south without bounds, a grey expanse of water. From the western base of the hill was a three hours’ march, though no march ever passed off so quickly. The hours seemed to have been quarters, we had seen so much that was novel and rare to us who had been travelling so long on the highlands. The mountains bounding the lake on the eastward receded and the lake advanced. We had crossed the Ruche, or Linche, and its thick belt of tall matted grass. We had plunged into a perfect forest of them and had entered into the cultivated fields which supply the port of Ujiji with vegetables, etc., and we stood at last on the summit of the last hill of the myriads we had crossed, and the port of Ujiji, embowered in palms, with the tiny waves of the silver waters of the Tanganyika rolling at its feet, was directly below us. We are now about descending—in a few minutes we shall have reached the spot where we imagine the object of our search—our fate will soon be decided. No one in that town knows we are coming; least of all do they know we are so close to them. If any of them ever heard of the white man at Unyanyembe they must believe we are there yet .… Well, we are but a mile from Ujiji now, and it is high time we should let them know a caravan is coming; so ’Commence firing’ is the word passed along the length of the column, and gladly do they begin. They have loaded their muskets half full, and they roar like the broadside of a line-of-battle ship. Down go the ramrods, sending huge charges home to the breech, and volley after volley is fired. The flags are fluttered; the banner of America is in front, waving joyfully; the guide is in the zenith of his glory. The former residents of Zanzita will know it directly and will wonder—as well they may—as to what it means. Never were the Stars and Stripes so beautiful to my mind—the breeze of the Tanganyika has such an effect on them. The guide blows his horn, and the shrill, wild clangour of it is far and near; and still the cannon muskets tell the noisy seconds. By this time the Arabs are fully alarmed; the natives of Ujiji, Waguha, Warundi, Wanguana, and I know not whom hurry up by the hundreds to ask what it all means—this fusillading, shouting, and blowing of horns and flag flying. There are Yambos shouted out to me by the dozen, and delighted Arabs have run up breathlessly to shake my hand and ask anxiously where I come from. But I have no patience with them. The expedition goes far too slow. I should like to settle the vexed question by one personal view. Where is he? Has he fled? Suddenly a man—a black man—at my elbow shouts in English, 'How do you do, sir?' 'Hello, who the deuce are you?' 'I am the servant of Dr Livingstone,' he says; and before I can ask any more questions he is running like a madman towards the town. We have at last entered the town. There are hundreds of people around me—I might say thousands without exaggeration, it seems to me. It is a grand triumphal procession. As we move, they move. All eyes are drawn towards us. The expedition at last comes to a halt; the journey is ended for a time; but I alone have a few more steps to make. There is a group of the most respectable Arabs, and as I come nearer I see the white face of an old man among them. He has a cap with a gold band around it, his dress is a short jacket of red blanket cloth, and his pants—well, I didn't observe. I am shaking hands with him. We raise our hats, and I say: 'Dr Livingstone, I presume?' And he says, 'Yes.' THE WHITE MAN’S BURDEN – RUDYARD KIPLING (1899) OVERVIEW This famous poem was a response to the American takeover of the Philippines after the Spanish-American War, though it reflects the general sentiments about imperialism held throughout the Western world at the time. Essentially, Kipling is urging the U.S. to continue to take on the “burden” of imperialism and bring “civilization to the savages” of the world. Some historians assert that Kipling wrote the piece as a satire, but many of his other works (including The Jungle Book) include pro-imperialist sentiments. Even if “The White Man’s Burden” was intended to be a satire, it is a valuable representation of the proimperialist attitudes of its time. Take up the White Man's burden-Send forth the best ye breed-Go bind your sons to exile To serve your captives' need; To wait in heavy harness, On fluttered folk and wild-Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child. Take up the White Man's burden-No tawdry rule of kings, But toil of serf and sweeper-The tale of common things. The ports ye shall not enter, The roads ye shall not tread, Go mark them with your living, And mark them with your dead. Take up the White Man's burden-In patience to abide, To veil the threat of terror And check the show of pride; By open speech and simple, An hundred times made plain To seek another's profit, And work another's gain. Take up the White Man's burden-And reap his old reward: The blame of those ye better, The hate of those ye guard-The cry of hosts ye humour (Ah, slowly!) toward the light:-"Why brought he us from bondage, Our loved Egyptian night?" Take up the White Man's burden-The savage wars of peace-Fill full the mouth of Famine And bid the sickness cease; And when your goal is nearest The end for others sought, Watch sloth and heathen Folly Bring all your hopes to nought. Take up the White Man's burden-Ye dare not stoop to less-Nor call too loud on Freedom To cloak your weariness; By all ye cry or whisper, By all ye leave or do, The silent, sullen peoples Shall weigh your gods and you. Take up the White Man's burden-Have done with childish days-The lightly proffered laurel, The easy, ungrudged praise. Comes now, to search your manhood Through all the thankless years Cold, edged with dear-bought wisdom, The judgment of your peers! THE BLACK MAN’S BURDEN – HUBERT HARRISON (1920) OVERVIEW Roughly 20 years after the publication of “The White Man’s Burden” an African-American from Harlem, NY wrote “The Black Man’s Burden” as a response to the ideology of European superiority and imperialist thought. In it he explains the dehumanizing impact of imperialism on non-Europeans. Though Harrison’s poem was focused on the struggles of blacks living in the U.S. the struggles he describes are generally true of peoples living under imperialism worldwide. Take up the Black Man’s burden--Send forth the worst ye breed, And bind our sons in shackles To serve your selfish greed; To wait in heavy harness Be-devilled and beguiled Until the Fates remove you From a world you have defiled. Take up the Black Man’s burden--Reduce their chiefs and kings To toil of serf and sweeper The lot of common things: Sodden their soil with slaughter, Ravish their lands with lead; Go, sign them with your living And seal them with your dead. Take up the black Man’s burden--Your lies may still abide To veil the threat of terror And check our racial pride; Your cannon, church and courthouse May still our sons constrain To seek the white man’s profit And work the white man’s gain. Take up the Black Man’s burden--And reap your old reward; The curse of those ye cozen, The hate of those ye barred From your Canadian cities And your Australian ports; And when they ask for meat and drink Go, girdle them with forts. Take up the Black Man’s burden--Reach out and hog the earth, And leave your workers hungry In the country of their birth; Then, when your goal is nearest, The end for which you fought Watch other’s trained efficiency Bring all your hope to naught. Take up the Black Man’s burden--Ye cannot stoop to less. Will not your fraud of "freedom" Still cloak your greediness? But, by the gods ye worship, And by the deeds ye do, These silent, sullen peoples Shall weigh your gods and you. Take up the Black Man’s burden--Until the tail is told, Until the balances of hate Bear down the beam of gold. And while ye wait remember The justice, though delayed Will hold you as her debtor Till the Black Man’s debt is paid.