Water Crisis in Central Asia: Key Challenges and

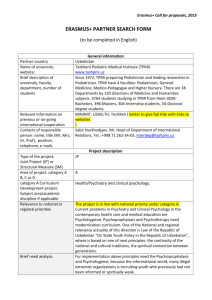

advertisement