14. The War for Independence

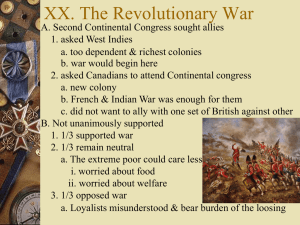

advertisement

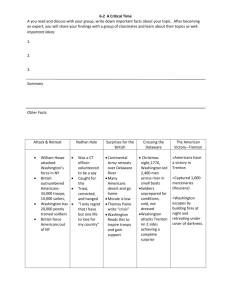

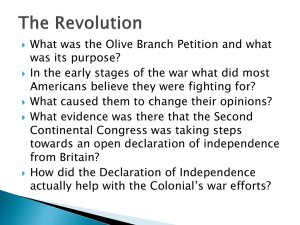

The War for Independence Ideas and protests were not sufficient to win independence soon enough to avoid war. India, in contrast, won independence from Britain merely through protests when the power of the photograph could provide “truer” propaganda. American colonists responded to the outrage of a standing army quartered in their midst by amassing weapons and supplies rather than by staging acts of civil disobedience. British awareness of colonial military preparations led to the battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill a year before the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Second Continental Congress. The War for Independence would last eight years, longer than any other American war save Viet Nam. This war proved to be a serious challenge to the supreme power of Great Britain in Europe; France nearly invaded England in 1779 as they allied with the fledgling United States of America to exact revenge for the loss of their North American empire. The early battles proved two things to the British. They were not fighting a mere mob, and the colonies were going to have to be conquered. England evacuated Boston, then, and transferred their main forces to New York. There were more loyalists in New York which also possessed the best harbor. In 1776, Sir William Howe replaced Gage as commander in chief over an army 30,000 strong. Howe’s goals were to cut off New England from the rest of the colonies and to defeat George Washington decisively in a battle. Before the shooting starts in earnest, the combatants should be compared and contrasted. The British had several advantages. Eleven million English squared off against only 2.5 million Americans. The Royal Navy was the largest in the world. England eventually fielded a well-trained army of 50,000 British troops and 30,000 German mercenaries. In contrast, the United States started from scratch in military preparation and never possessed a navy. Washington fielded as few as 5,000 “professional” soldiers, at times, and the rest of his forces were untrained militia with inexperienced officers. Great Britain won by far the majority of the roughly 83 battles of the war, but the US had two advantages. The 3,000-mile distance hampered British communication and supply. Furthermore, while the Continental Army was perhaps conquerable, the continent itself was too big to conquer, in the end. There was no vital center for England to crush. The disorganization of the rebel army actually helped prevent an all-out confrontation which would have been disastrous for the United States. Remember this aphorism for later reference—locals fighting for their homes over known terrain with popular support make a nearly indestructible force. An analysis of the miracle of an eventual American victory shows that independence meant more to Americans than keeping the colonies did to Great Britain. Independence was a simple and clear idea unlike imperial rule and mercantilism. Even if England did conquer the Continental Army there would not necessarily have been peace. Many British officers did not believe as Parliament did that outright conquest of brethren was a good goal. The first Generals kept offering peace to the Continental Congress and did not permit plundering, which hurt the morale of British soldiers. Fierce fighting broke out as Washington tried to harass the British in New York. At the Battle of the Brooklyn Heights, the British fired grape shot and chain into oncoming American troops. Grape shot consists of small iron balls and when used, turned cannon into giant shotguns. “Chain” refers to the practice of firing two cannon balls out of the same cannon with the balls are chained together. The result is a spinning saw designed to cut down masts of ships. It worked well on men, too. George Washington retreated south, and the British occupied all of New York and New Jersey. Five thousand New Jersey citizens took an oath of loyalty to the Crown, and some of the bitterest fighting of the war was touched off by patriot/loyalist clashes among Americans. Washington then proved his pluck and courage by mounting a surprise attack across the Delaware River. He moved 2,400 troops across the nearly-frozen river and captured Trenton on Dec. 26th, 1776 and Princeton on Jan. 3rd, 1777 with the loss of only five American casualties. These moves caused the British to withdraw and limited the extent of military occupation. The next big British initiative proved the British army’s capacity to do the wrong thing at the wrong time. In 1777, England mounted a three-pronged attack to crush resistance in New England. General John Burgoyne led the first prong of 8,000 troops south through Lake Champlain to Fort Ticonderoga. Colonel Barry St. Leger drove east from Lake Ontario, and General Howe came north from New York. This plan sounds like a devastating finishing blow that would forever bury the hopes of independence, but three-pronged attacks rarely go well. The only men who could consistently pull them off were Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and they weren’t born yet. Gen. Howe decided to act independently and capture the capital in Philadelphia in order to draw loyalist support. Washington tried twice to stop him but was defeated at Brandywine and Germantown. Congress fled. But Howe bogged down in Philadelphia and wound up spending the winter there. Meanwhile, St. Leger’s force was turned back at Oriskany, NY, by the American General (hero!) Benedict Arnold. These developments left Burgoyne alone. His supply line from Canada was thin, and his flanks were harassed by New England militia. 900 British were separated and defeated by John Stark and 2,000 Americans in Vermont. Burgoyne peeled off 900, himself, to garrison Fort Ticonderoga. Therefore, when he marched to Saratoga, he had only 6,200 men. When he had hoped to meet up with the other British armies, he met up with 10,000 American troops under General Horatio Gates. By October of 1777, Burgoyne surrendered his entire force to Gates after seeing the hopelessness of his situation. Saratoga is a major turning point in the war and one of the two battles you should memorize. Britain experienced the first hint that re-conquest might be impossible. Both sides thought France might join the war against Britain. The French wanted revenge so badly that they had secretly been supplying the Continental Army from the beginning. Benjamin Franklin had opened diplomatic talks with France from 1776-77. French officers joined Washington’s army, and France had the one thing America most needed, a navy. When France was thought to be entering the war, Great Britain offered to return colonists to their position before the Treaty of Paris, 1763, which would have granted everything the colonists originally wanted, minus independence, of course. Franklin deftly used this potential reunion of the colonies with England to bluff the French king, Louis XVI, to form a commercial alliance and then a military alliance in February of 1778. The balance of power in Europe kicked in and Spain allied with France to get back land it had lost to the British. By 1780, even Russia had formed an Anti-British European League. All of these events turned on the surprise victory at Saratoga. Howe was replaced by Sir Henry Clinton. Clinton redoubled England’s efforts at sea and moved the military focus south. British forces began bombarding American ports and raiding the countryside to break the support of the patriot cause. England thought it would find more loyalist support in the aristocratic South, then sweep north to meet forces from New York pushing south in a giant pincer movement. Clinton captured Savannah late in 1778. On May 12, 1780, he dealt America its greatest loss of the war with the surrender of 5,500 troops at the fall of Charleston. When Gates, the hero of Saratoga, was sent south to oppose the British advance, he was defeated at Camden, South Carolina. Through this fighting, the brutality of the British swayed many to support the patriots. Guerrilla warfare broke out. Lord Cornwallis, in charge of the march north, sought to make a big push into North Carolina. His forces were harassed by guerrilla fighters, then, the Battle of King’s Mountain happened on Oct. 7, 1780. The Overmountain Men were frontiersman from what would become Tennessee who mustered near Bristol and marched across the Appalachian Mountains to meet the British threat. These fighters were such accurate shooters that they defeated the British at King’s Mountain even though the British held the top of the mountain at the beginning of the battle. His left flank exposed, Cornwallis returned to South Carolina. Thomas Jefferson would later call this battle a key to winning the war. Go Vols! Nathaniel Greene, interestingly an ex-Quaker pacifist, led American forces in the south. He avoided confrontation but caused the British to divide their forces. On January 17, 1781, Daniel Morgan defeated Tarleton’s forces at Cowpens. Tarleton had been the British officer guilty of most of the atrocities on patriot families and supporters. Cornwallis tried to chase the American forces, but he wound up giving up South Carolina. Finding himself in Virginia, he tried to hold that. By August of 1781 Cornwallis was isolated and picked off by Washington with the help of the Marquis de Lafayette, a French aristocrat who had come to fight in America largely because he was bored. Washington’s force worked with a French force under the Comte de Rochambeau to corner Cornwallis at the other of the two battles you should memorize, Yorktown. Cornwallis’s 8,000 were surrounded by land with 17,000 American and French, and the French fleet under Admiral Degrasse cut off his escape by sea by September of 1781. On October 19, Cornwallis said, “The game is lost,” and surrendered his force after a prolonged bombardment. The war took a long while to wind down. Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay traveled to Paris for yet another Treaty of Paris, this time in 1783. This document is our real birth certificate, not the Declaration of Independence, in that it proves we had fought the most powerful military in the world and won. The treaty spelled out our boundaries: the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River in the West to Canada and down to Florida, which America returned to Spain (for now). The land contained on that map was more than any European nation thought possible, and we could hardly believe it, ourselves.