A Quick Guide to Understanding Parliamentary Debate

advertisement

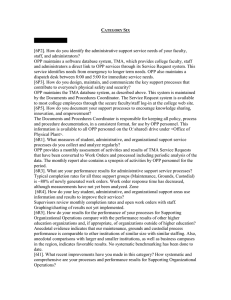

A Quick Guide to Understanding Parliamentary Debate Part 3: the Opposition OPP responsibilities When a resolution is assigned and the teams shuffle off to prepare their case, there is only so much that OPP is able to do. Since the responsibility of defining and setting the criteria lies with GOV, all OPP can do is anticipate what the case may or may not be and prepare potential lines of refutation. Once the debate begins and the PM has laid out the parameters of the debate, the OPP is faced with the choice of accepting the terms of the debate (i.e. definitions and criteria) or rejecting them. In general OPP should only take issue and reject a part (or all) of GOV’s parameter’s if they believe that one or more of the following has happened. 1) That the definitions put forth by GOV are too narrow or too vague and skew argumentative ground in favor of the GOV. 2) That GOV’s interpretation of the resolution is in no way related to its original meaning (topicality violation) 3) That the criteria is unfair, confusing, or maybe there’s just an easier way to decide the debate If OPP rejects any or all of GOV’s initial parameters, then it is imperative that they offer counter-parameters then (i.e. counter definition, counter-criteria etc.) In order to successfully reject OPP must argue as to WHY the original definition/criteria/etc is bad and their counter definition/criteria/etc is better for all. Typically this line of argumentation leads to dull semantic debates and is not very productive, drains time from other, more pressing issues, and will make your audience cranky. Avoid this if you can, but if you do then stick to your guns. THE PRIMARY GOAL OF THE OPPOSITION TEAM is to disprove GOV’s case. Their sole objective is to poke as many holes in the logic of GOV’s case until it is too weak and wobbly to stand. However, relying on this one task may not be enough when faced with a solid GOV’s case. Therefore OPP has the privilege to create a set of unique and distinct arguments designed to prove how the resolution is not true. This is called OFF-CASE. Off-Case Off-Case arguments are designed to disprove the resolution and are separate from the refutational arguments against the GOV’s case. For example if the resolution is “THB it is better to give than to receive” then OPP’s off-case arguments focus on proving how/why it is NOT better to give than receive. These arguments are different than the refutation of GOV’s case. It will then become the responsibility of the GOV to not only address lines of refutation to their original case, but then also attack and refute the OPP’s off-case arguments.