Mobilization and Medicalization: Electronic Support Groups and

advertisement

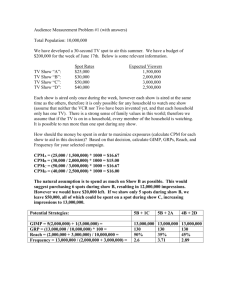

1 Mobilization and Medicalization: Electronic Support Groups and Contested Illness Kristin K. Barker Department of Sociology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; kristin.barker@oregonstate.edu. Abstract For millions of sufferers, living with a functional somatic syndrome means managing a constellation of chronic and often debilitating symptoms in the context of medical marginality. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that there has been a proliferation of electronic support groups (ESGs) run for and by sufferers of these contested illnesses. Anecdotal reports from participants suggest that ESGs provide invaluable information and support that can significantly alleviate the impacts of living with a contested illness. Sceptical clinicians, in contrast, accuse ESGs of contributing to the spread of these diagnoses by circulating misinformation and encouraging maladaptive illness behaviour. Beyond such anecdotes and polemics, however, we know very little about the functioning of these ESGs. This paper is based on a non-participant, ethnographic study of a year in the life of an ESG for sufferers of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS). The analysis focuses on how the dominant beliefs and routine practices of this electronic community, grounded in shared embodied suffering, represent challenges to biomedicine and the doctor-patient relationship at the same time that they encourage the expansion of biomedical authority. The paper, thus, provides a concrete example of how participants within a health movement ESG mobilize around a contested illness identity, challenge medicine’s authority as patient-consumers, and actively contribute to processes of medicalization. Introduction More than ten million Americans, most of them women, are diagnosed with a functional somatic syndrome, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, or multiple chemical sensitivity (Barsky & Borus, 1999; Manu, 1998; Wessley, Nimnuan, & Sharpe, 1999). These overlapping illnesses are characterized by a host of common symptoms including chronic pain, fatigue, headaches, sleep and bowel irregularities, and cognitive and mood 2 disorders. By definition, functional somatic syndromes are not linked to any known organic abnormality, and, as such, many physicians approach these diagnoses with a considerable degree of scepticism (Asbring and Narvanen 2003; Crofford and Clauw 2002). The fact that these syndromes respond poorly to established medical treatment only further fuels medical suspicions (Asbring and Narvanen 2002; Goldenberg et al. 2004). In simple terms, what is at issue in the minds of many clinicians is whether these syndromes are “real” (i.e., they have physical origins) or not (i.e., they are psychosomatic). For the millions of women sufferers, living with a functional somatic syndrome means managing a constellation of chronic and often debilitating symptoms in the context of medical marginality. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that there has been a proliferation of electronic support groups (ESGs) operated for and by sufferers of these syndromes. Accessed as bulletin boards, newsgroups, listserves, and chatrooms, ESGs take the form of electronic postings in which individuals — in real or delayed time — write, send, and read textual messages. Anecdotal reports from participants suggest that ESGs provide invaluable information and support that significantly alleviates the distressing symptoms and the self-discrediting impact of living with a contested illness (Barker, 2005; WebMD, 2005). In contrast, skeptical clinicians accuse ESGs of contributing to the spread of these diagnoses by circulating medical misinformation 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to the worried and anxious; reinforcing maladaptive illness behavior (e.g., individuals seeking to prove they are ill through solidarity with others); and encouraging sufferers to shop for “friendly” doctors who are predisposed to confirm the diagnosis (Bohr, 1996; Hadler, 1999). Beyond such anecdotes and polemics, 3 however, we know very little about the functioning and consequences of ESGs for sufferers of these syndromes. While sufferers and clinicians debate the merits of ESGs, medical sociologists are also raising questions about the influence these groups have on the illness experience (Hardey, 1999, 2001; Henwood, Wyatt, Hart, & Smith, 2003). The Internet in general, and ESGs in particular, provide individuals with unprecedented access to health information and have turned the process of understanding one’s embodied distress from an essentially private affair between doctor and patient to an increasingly public accomplishment among sufferers in cyberspace. On one hand, the democratizing impulse represented by increased access to medical information is to be applauded; challenges to professional hegemony and patient self-empowerment are rightly seen as positive outcomes (Clarke, Mamo, Fishman, Shim, & Fosket, 2003). On the other hand, the increased production and exchange of lay information via ESGs and other Internet communities have been identified as contributing to “medicalization,” or the process by which human experiences that are neither inherently nor fully medical in character come to be defined, experienced, and treated as medical conditions. Whereas physicians’ professional power and ambition was a principle force facilitating medicalization in the 20th century (Freidson, 1972; Illich, 1976), Conrad (2005) has recently called on sociologists to investigate the role played by “patient-consumers,” including those who form Internet support groups, in defining their own problems as medical and functioning as an important “engine of medicalization” in the 21st century. It would seem plausible that this trend would be particularly pronounced in the case of contested illnesses, where sufferers seek the very medical recognition that physicians are reticent to provide. 4 Although they did not focus on the Internet or ESGs, a group of medical sociologists have written a series of articles in which they portray the collective mobilization of sufferers of contested illnesses as an example of what they call “embodied health movements” (Brown & Zavestoski, 2004; Brown et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2004; Zavestoski, Morello-Frosch et al., 2004). Embodied health movements (EHMs) draw on the embodied experience of suffering to challenge orthodox medical practices and knowledge. In the case of groups run by contested illness sufferers, the principal goal of this challenge is to achieve medical recognition in the form of diagnosis, treatment, and research (Brown et al., 2004). This body of scholarship presents a provocative theoretical typology of embodied health movements, but, as a result of its empirical focus, it has not examined how sufferers of contested illnesses interact within social movement organizations to collectively frame and articulate their grievances. Moreover, this research has underemphasized the link between embodied health movements and medicalization; that is, it has not fully explored the role groups within these movements play in creating “patient-consumers” and expanding the jurisdiction of medicine.1 In sum, there is a need to understand the role of contested illness ESGs on the illness experience, including their potential contribution to processes of medicalization; and, there is a need to understand the actual mechanism by which individuals mobilize around contested illness identities to challenge medical authority, in hopes, ironically, of broadening the sphere of medical authority. This paper is based on a study of a year in the life of a fibromyalgia syndrome ESG. More specifically, the analysis presented in this paper is based on a non- 5 participant, ethnographic study of all postings to a bulletin board group given the pseudonym Fibro Spot from February 2004 to February 2005. Fibro Spot is a cybercommunity with its own elaborate and distinctive cultural practices, but this paper will focus specifically the role that these kinds of groups and this new technology play in the medicalization process. In sum, this paper provides a concrete illustration of how the routine, everyday practices of individuals in an embodied health movement organization – an illness-based ESG for sufferers of fibromyalgia – mobilize around a contested illness identity, challenge medicine’s authority as patient-consumers, and actively contribute to processes of medicalization. Fibro Spot: An Electronic Ethnography Fibro Spot is an open bulletin board system that has been in existence for nearly ten years. It was maintained on a server owned by one of the original group members until 2000, at which time several members collectively purchased the group’s current domain name and site. The group’s history as a lay created and maintained ESGs is typical of the many ESGs for sufferers of functional somatic syndromes that have emerged during the last decade. All textual materials posted to Fibro Spot during the twelve-month period under observation were downloaded for analysis using computer assisted text analysis software. Insofar as they capture all the activities of a group, downloaded electronic communications can be thought of as nearly perfect field notes (Stone, 1995). Nevertheless, using such data does raise a host of methodological and ethical concerns. With regard to the former, some electronic ethnographers claim that “ethnographic” analysis must be derived from the researcher’s interactions with on-line participants. 6 Researchers who lurk, it is argued, “relinquish claims to the kind of ethnographic authority that comes from exposing emergent analysis to challenge through interaction” (Hine, 2000: 48). This claim fails to stand up to rigorous scrutiny, as have a host of similar claims regarding heretofore-sacred features of the ethnographic approach (i.e., necessity of travel to distant places, the notion of the “field” as a bounded social space, the imperative of face-to-face interaction, and the marginal importance of “texts” to the understanding of deep culture). Ironically, electronic ethnographers are among those individuals responsible for successfully challenging these other sacrosanct ethnographic imperatives. Ethnography is the description of human social phenomena derived from raw data collected during fieldwork, which is a term used to describe a prolonged period during which researchers submerge themselves in the routines of a particular social environment. Even though specific ideas about how and where authentic ethnographic research can be conducted have shifted dramatically over the last several decades (Clifford & Marcus, 1986; Denzin, 1987), these general claims about the essence of ethnography remain widely shared (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1995). By these standards, the essence of ethnography can be realized even when researchers are non-participants in electronic forums. In fact, it possible for the electronic researcher to observe more fully the routine practices of a given social environment than is possible with conventional ethnography, where researchers are limited to what can be observed in real time, in a fixed space. Likewise, the natural practices and interactions of a social environment remain undisturbed by non-participant researchers (Dickerson, Flaig, & Kennedy, 2001), 7 allowing them to observe minute and intimate everyday social practices at a level of detail rarely, if ever, achievable by conventional methods. However, unlike conventional ethnography, which privileges more “traditional” modes of human communication (e.g., performed rituals, the spoken word, and face-toface interaction); electronic ethnography is necessarily a text-based endeavor. ESGs exist as text. But electronic postings are not simply texts; they are also interactions. Consequently, in addition to coding Fibro Spot postings for thematic content of the group’s everyday practices, particular attention is paid to the interactive threads that tie individual postings, and, therefore individual participants, to one another in a network of social interaction. There are also ethical concerns when it comes to using downloaded communications as ethnographic data. Fibro Spot was selected for a variety of reasons that showcase the current debate among researchers within numerous academic disciplines and professional fields about what privacy ESG participants should expect given the public nature of Internet exchanges. First, the group is an open bulletin board, which means that it does not require users to register or subscribe. When an ESG requires registration, the group is less public. Second, Fibro Spot is a large group. With well over two hundred participants, individuals are far less likely to feel their postings are intimate than would individuals in a group with only a small handful of participants. This is even more likely to be the case given that the group archives its exchanges on its home page. By providing a full electronic history of its postings, Fibro Spot intentionally increases its public visibility beyond its current and active participants. Finally, there is nothing posted on Fibro Spot’s webpage outlining “netiquette” restrictions concerning who is free 8 to use the materials, who owns or has copyright to the posted materials, and the like. In contrast, WebMD, the largest e-health site, operates ESGs that contain the postings of thousands of persons, but, legally, they claim ownership over all the material that appears on their website. For all of these reasons, outlined by leading ESG researchers (Eysenbach & Till, 2001), we can say that Fibro Spot is significantly more public than private.2 Between February 2004 and February 2005 there were 249 participants of Fibro Spot who collectively contributed a total of 1,814 postings. The frequency with which these individuals participated during the year varied considerably (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Of the 249 participants, 113 persons (roughly 45%) posted only one entry during the entire year. An additional 56 persons (roughly 22%) posted 2 or 3 entries. Consequently, the overwhelming majority of participants (nearly 70%) quickly dropped in and then out of Fibro Spot. In contrast, there were some individuals who contributed postings with more regularity, including some who were highly active participants. For example, 16% of individuals posted between 4 and 10 entries, slightly more than 8% posted between 11 and 20 entries, and slightly less than 8% posted more than 21 entries during the course of the year. Only three individuals posted at least one entry a month, and the most active participant contributed a total of 145 postings. As seen in Figure 1, together nineteen individuals contributed 1,012 of the postings during the year observed, or more than 50% of all postings. Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that, in all likelihood, the most common “participants” of Fibro Spot are lurkers, that is, individuals who never post a single message, but observe the participation of others. In a study that monitored an ESG for smoking cessation, lurkers constituted 95% of those who logged onto the group’s site 9 (Schneider, Walter, & O'Donnell, 1990). Although we can only speak in general terms in the absence of data, it is safe to assume that lurkers are common and frequent visitors at Fibro Spot. 10 Table 1: Number of Postings (NOP) to Fibro Spot ______________________________________________________________________ Number of Number of Pct of people Cum pct Total Pct of total postings by people w/ with this of people NOP postings individual this NOP NOP w/ this NOP ______________________________________________________________________ 1 2 3 4-10 11-20 21+ 113 40 16 40 21 19 45.4 16.1 6.4 16.1 8.4 7.6 45.4 61.5 67.9 84.0 92.4 100.0 113 80 48 242 319 1012 6.2 4.4 2.6 13.3 17.6 56.0 Total 249 100.0 100.0 1814 100.0 ______________________________________________________________________ Note — Mean = 7.28; Median = 2; Mode = 1; Maximum = 145. Figure 1: Number of Postings (NOP) to Fibro Spot 1200 1000 800 600 People (249) Total NOP (1814) 400 200 0 1 2 3 4-10 11-20 21+ post posts posts posts posts posts 11 Electronic Support Groups and Contested Illness: Mobilization for Medicalization According to Conrad (2005:3), medicalization happens when some problem gets defined in medical terms, “usually as an illness or disorder, or using a medical intervention to treat it.” ESGs like Fibro Spot provide individuals — active participants and lurkers alike — with the opportunity to come together to make sense of their suffering. By writing and/or reading about their distress, ESG participants collectively define their problem and its remedy. Participants at Fibro Spot consistently and emphatically define their problem as a discrete medical illness (i.e., ‘fibromyalgia’), one that they share with many others. Moreover, participants bemoan the fact that, even though fibromyalgia requires medical intervention, many physicians consider it to be a psychosomatic condition. Accordingly, many physicians will not diagnosis fibromyalgia, recognize the fibromyalgia diagnosis, or treat fibromyalgia patients (Asbring & Narvanen, 2003; Crofford & Clauw, 2002). It is this tension that underlies the everyday routines and practices of Fibro Spot that produce patient-consumers who simultaneously challenge medical authority and facilitate medicalization. What follows are examples of these routines and practices. Example 1: Doctors Don’t Have a Clue Sarah: Hello Family! […]3 my new doctor appointment was today. Was not good!! First of all she is 4 months out of medical school. She looked over my chart and immediately wanted to change all medications that I am taking. … I said no, the ones I am taking now are just fine. She wasn’t pleased about that. Now about your fibromyalgia, I will not prescribe pain killers for fibro. I sat there with my mouth open. She went on to tell me that fresh out of med school approach to fibro is excercise, diet. I said what about the pain. She preceeded to tell me the pain was “ALL IN MY HEAD, THERE IS NO PAIN, YOU JUST IMAGINE THERE IS.” My first thought was jump up out of this chair and slap the B----!! Instead I said you are an idiot!! Then I walked out. [...] She is a doctor at a large clinic in [city where she lives]. So I …called their patient advocacy phone line to report 12 the way I was treated. So if anyone … knows a doctor in my town … please, please, please e-mail me. I cannot even count the number of doctors I have been to, to just get diagnosed. Gini: Good Evening FM’ily- Sarah- I am so sorry that you were treated that way. It’s scary that some doctor’s have so much ego and ignorance about this disease. I hope you have luck finding a new doctor. Vivian: Sarah -- I’m sorry you had to go through that ordeal with your new doctor who truly is ignorant on the subject of fibromyalgia ... I hope you find a new one soon who is knowledgeable about fibro instead. I went through the same thing with 2 of my doctors telling me that most doctors did not believe fibromyalgia exists.… I really didn’t have time to waste with this kind of nonsense. I told one of the docs that he didn’t have a clue. Marilyn: Oh, Sarah, I’m so sorry about your appointment. That has to be one of the worst nightmares of Fibro. It’s like having a car that won’t start, and standing in front of a mechanic who says, “There's nothing wrong with it.” You CAN’T fix it yourself, and now you have to find someone else. […] I think your doc has not seen enough pain in school to be compassionate and willing to deal with pain. You can’t truly learn about dis-ease in a book or a school. You should have kicked her in the shins and asked if it felt like it was in her head! This is a highly typical exchange on Fibro Spot,4 and, in it, we see a number of ways participants confront medical expertise by demanding that their embodied distress be recognized and treated in medical terms. Sarah describes challenging her doctor’s refusal to prescribe pain medications. The reluctance of physicians to prescribe pain medications to women patients is well documented (Calderone, 1990; Hoffmann & Tarzian, 2001), and is a perennial compliant of fibromyalgia sufferers (Barker, 2005). Sarah also rejects her doctor’s advice to treat fibromyalgia with diet and exercise, and is incensed by the interpretation that her pain is a psychosomatic symptom over which she has control. Sarah, in short, is outraged. In response, she calls her doctor an idiot, storms out of the doctor’s office, reports being ill-treated to the clinic where her doctor is employed, chronicles her experience to her fibromyalgia “family,” and begins the search for a more sympathetic provider. 13 Several Fibro Spot participants respond with supportive indignation. Gini and Vivian assure Sarah that her doctor displayed profound ignorance and wish her well in her search for a competent replacement. Vivian describes how she, too, confronted inept physicians who questioned the existence of fibromyalgia, telling one of them “he didn’t have clue.” Marilyn echoes these sympathetic comments, but she also highlights their dependency on the equivalent of a medical “mechanic” to fix them. Unfortunately, the mechanic can’t find anything wrong; these patients appear to be in working order. Their apparent well being is troubling, or in Marilyn’s words, “one of the worst nightmares of fibromyalgia.” The “dis-ease” of pain isn’t visible, neither is it something that one can learn about in medical school. The best way to understand pain, Marilyn remarks, is to experience pain. She cleverly drives home the point by suggesting that a kick in the shins would convince the doctor that pain is real and not merely in one’s head. In this way, Marilyn’s comment highlights another persistent theme found in the routine exchanges at Fibro Spot; namely, the inherent validity of embodied experience. Example 2: The Validity of Embodied Experience A defining feature of embodied health movements is that they “use the body as a counter-authority to challenge science in its epistemological processes and its institutional forms” (Zavestoski, Morello-Frosch et al., 2004: 254). The postings from Fibro Spot participants convey in no uncertain terms a belief that their shared embodied experience trumps the objective or expert knowledge of doctors. The following exchange is exemplar of this sentiment. Angela: One of my doctors warned me about places like this [online groups], telling me I would read what others wrote and then have the same symptoms myself. ... I can’t believe that this is true but while I read some 14 of the old posts, I remember saying to myself, “I have that, or yes that is what I feel.” Yolanda: Don’t let doctors treat you like some type of idiot. That’s how they deal with not dealing with FMS. It’s too big of a pain for some of them to acknowledge they don’t know enough about it and can’t fix it. What I find in reading others’ symptoms, etc. is that i’m not nuts, and this really is happening to me. Find a different doctor; … take control of your management of your life and the fibro. Susie: Angela, Don’t let your doctor tell you that you will “feel” what you read ... you will finally find out what you feel is real!! They don’t usually like that because then you come back to them saying “HEY! This is wrong and I want us to work on it!” Hang in there dear one ... find a new doctor. In the above exchange, Yolanda and Susie both encourage Angela to disregard what her doctor has told her about the contaminating influences of ESG participation. Further, they explain to Angela that reading the posts of others merely confirms the reality of their collective experience, and, therefore, the reality of fibromyalgia. It is inconceivable that their suffering and fibromyalgia are not real, given that they all experience such similar symptoms. When doctors fail to acknowledge this reality, participants attribute it to ignorance, arrogance, or both. According to participants, doctors are in no position to tell sufferers what they feel. When a doctor does so, it’s time to find a new doctor. Through their social interactions, sufferers affirm the reality of their shared illness and embolden one another to move on in search of a doctor willing to confirm that reality. In other words, Fibro Spot participants use the experienced body as a counter-authority to defy biomedicine’s epistemological assumptions and institutional hierarchy. Example 3: Doctors are not God The next exchange further underscores how participants at Fibro Spot defy biomedicine’s institutional hierarchy when doctors discredit their embodied experience. 15 Becky: I know that several of you have had problems with doctors. I wanted to share my recent experience with a new primary care doctor. […] She had told me that I could control the pain with my head…She had said to me, “The pain is not killing you. You are not dying from it”. She also told me to get a job and that she didn’t like couch potatoes. … Anyways, I decided to go back to her one last time, but this time was going to be different. This time I was in charge. I told her that I strongly believe that doctors don’t realize what an impact they can have on their patients. I told her how she put me on the verge of suicide and that I felt that she wasn’t really listening to me. I explained all about my new diagnosis and my difficulty in showering, dressing, lifting a glass of water, and walking. I explained my pain to her in detail. After all was said and done she said, “I don’t believe you are disabled”. I replied, “Then this conversation is over”!!! ... My reason for sharing is that we can not let doctors intimate (sic) us anymore. When we go to them we aren’t feeling well, we’re in alot of pain, and we are feeling very vulnerable. From now on I will not let this happen. If when I get a new primary he or she isn’t listening or treats me in a way that I don’t want to be treated then I will tell him or her and I will find a new doctor… I feel that this is important…. Instead of letting doctors get us down let us take control of the situation. Afterall, we choose them and pay them not the other way around. They are not God and we are not at their mercy. Gretchen: Thanks Becky for your inspirational words. The hard thing about being sick is that you don’t feel good. When you don't feel good it is harder to fight for what you need. It’s kind of ironic. The ones that need the most help have the softest voices. God willing, I am going to do something to get FM on the national map. I’ll start with here. […] People in chronic pain need chronic pain medicine. […] Just give us what we need and we'll go away. That is what I would like to say to someone. I don't know who yet. I'll figure it out. Becky’s posting chronicles a single patient’s willingness to dispute professional authority. When Becky angrily returns to meet with her primary care physician, she tells the physician the diagnosis for her condition. She also explains the functional limitations of her illness, which her doctor rejects. Becky ends the encounter with a confrontation and then uses the experience as a call to action. She encourages others at Fibro Spot to confront doubting physicians and take control of the situation. They need to find doctors that are willing to listen to them, believe in what they say, and treat them the way they 16 want to be treated. After all, Becky reminds her fellow sufferers, doctors are not God. Rather, patients pay them, and the customer is always right. Gretchen thanks Becky for her inspiring call to action at the same time she describes the difficulties associated with fighting back when one is exhausted by illness, and when one’s calls for help go routinely unheeded. Despite her soft voice, Gretchen vows to bring national attention to their shared plight. Although she is uncertain whom to tell, she wants someone to hear her: “Just give us what we need and we'll go away.” Patient-Consumers and Doctor Compliance All three of the above examples reveal routine exchanges through which participants at Fibro Spot construct a contested illness identity (i.e., a shared sense of embodied suffering and medical marginalization). Participants mobilize around this identity to confront medical authority and demand medical reconition and services. All three of the above examples, therefore, reveal patient-consumers’ unwavering demand for what I call “doctor compliance.” Physicians and health researchers have long been interested in improving patient complaince. Accordingly, they study ways to increase the likelihood that patients will follow doctors’ orders. Medical sociologists critique much of this research on grounds that it conceptualizes the ideal patient as an “obedient and unquestioning recipient of medical instructions” and attributes non-compliance to patient irrationalities (Stimson, 1974: 97). In effect, the sociological critique of this research is that the very notion of patient compliance represents a form of social control premised on unquestioning acceptance of medical authority. What is frequently at issue in the case of contested illness is doctor compliance. Through their routine social exchanges, Fibro Spot participants define the ideal doctor as 17 an obedient and unquestioning recipient of the patient’s instructions and attribute noncompliance to doctor irrationalities. Doctors must, that is, accept patients’ definition of the situation (i.e., they have a discrete physical illness) and the definition of the solution (i.e., they need a fibromyalgia diagnosis and access to the host of medical treatments, and social and economic resources used by fellow sufferers). Of course, it is important not to overstate the power patients have within the doctor-patient relationship. Physicians remain powerful gatekeepers to medical and social resources upon which patients are frequently dependent. Indeed, it is precisely this dependency that fuels the existence of groups like Fibro Spot. Nevertheless, as seen in these typical exchanges, demands for doctor compliance premised on an unquestioning acceptance of embodied experiential authority, do represent a significant challenge to the beliefs and practices of biomedicine. At the same time, however, the challenge advanced by patient-consumers calls for the intrusion of medicine into terrain that it does not currently recognize as part of its jurisdiction. In this way, challenges to medical authority and demands for medicalization become one. Fibro Spot, Medicalization, and Health Movements The collective life of Fibro Spot contributes to medicalization, not because the symptoms described as fibromyalgia are not real or all in the heads of sufferers. The core symptoms of fibromyalgia (e.g., pain, fatigue, headaches, sleep and bowel irregularities, and cognitive and mood disorders) are regrettably common in the general (healthy) public (especially among women). Nevertheless, through routine social interaction on the basis of these very real and, yet, very common symptoms, the notion of a disease entity becomes reified, even in the absence of orthodox biomedical evidence. From the perspective of Fibro Spot participants fibromyalgia must be real. Otherwise, why would 18 they all experience such similar symptoms? Accordingly, patients enter into a clinical encounter armed with the indisputable authority of their shared illness and a concomitant demand for doctor compliance. If such compliance is not forthcoming, patient-consumers continue shopping for what they really want. Unfortunately, what they really want — the medicalization of a vast constellation of women’s common somatic complaints under the rubric of fibromyalgia — offers very little remedy. In one of the exchanges presented earlier, Marilyn draws attention to the dependency of sufferers on a medical “mechanic” to fix them. This metaphor is not without limitations. Although, like Marilyn, most sufferers believe you can’t fix fibromyalgia yourself, they are also acutely aware that no medical therapy is particularly effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia (Barker, 2005). For example, recall Yolanda’s remark: “It’s too big of a pain for some of them to acknowledge they don’t know enough about it [fibromyalgia] and can’t fix it.” Although participants at Fibro Spot call for medicine to intervene into women’s routine bodies and lives, they do so with an understanding that this intervention brings few obvious therapeutic benefits. Overall, there is scant evidence that being diagnosed with and treated for fibromyalgia translates into any long-term improvement in health status (Goldenberg, Burckhardt, & Crofford, 2004; Wolfe et al., 1997). Our understanding of the demands of Fibro Spot participants is advanced by recognizing that health movements have created dramatic changes in the health care landscape and cultural ideas about health care delivery (Brown & Zavestoski, 2004). For example, some of the demands made by Fibro Spot participants are an extension of those made by activists from the women’s health movement of the 1970s. At the same time, 19 however, many of their stated grievances are peculiarly at odds with the ethos of that movement. The spirit of the 1970s women’s health movement, captured in the book title, Our Bodies, Ourselves, was a call for laywomen to take control of their own bodies; for women to take their health care “into their own hands” (Morgen, 2002). This book was the joint project of a small group of women who felt a bewildering lack of knowledge about their own bodies and questioned how and why male doctors controlled this knowledge. In response, the women studied and taught each other about different aspects of women’s bodies and their mimeographed notes served as the basis for the first edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves, published in 1970. The women’s health movement originally focused on the medical control of women’s reproductive bodies, but ultimately it advanced a more general and systematic critique of medicine as an institution that both reflected and reproduced patriarchical gender relations (Ehrenreich & English, 1972, 1973). For example, one reason women lacked knowledge about their bodies is that physicians in patriarchial societies treat women like children, thereby denying them information necessary to make decisions and sometimes taking decision-making power away from them altogether. Similarly, medicine too often dismisses women’s complaints as hysterical and commonly defines women’s bodies (and, by extension, their nature) as inherently unstable and volatile (Martin, 1987). Key goals of the women’s health movement, therefore, were to empower women to become active agents in their own health-care decision-making, and develop a consciousness about the patriarchal bias embedded in the doctor-patient relationship and medical knowledge claims. 20 The women of Fibro Spot are the beneficiaries of these specific victories of the women’s health movement. For example, they are actively hostile to physicians who trivialize their suffering, suggest they are hysterical, treat them in a condescending manner, or refuse to provide them with needed information and resources. But not only did the early women’s health movement challenge medical authority and demand that women be allowed to take an active role in their own medical decision making, it also demanded the demedicalization of women’s routine health care. Importantly, the movement fought against medical control of women’s routine bodies. The legalization of lay midwifery, for example, was a key demand of the movement. Likewise, self-help, as outlined in Our Bodies, Ourselves, was a principle way for women to resist medical control of their bodies. In her appraisal of the women’s health movement, Sheryl Burt Ruzek (1978: 14) notes that a goal of the movement was to deinstitutionalize and deprofessionalize women’s routine care so that it could be returned to the jurisdiction of female culture and women could care for themselves and for one another. These were necessary goals because medicine had long been overzealous in its tendency to see women’s bodies as inherently pathological, thereby sanctioning unnecessary, and sometimes harmful, medical surveillance and treatment. These radical impulses of the early women’s health movement are seemingly absent from the exchanges at Fibro Spot. Instead, they advocate for an expansion of medical authority over their own bodies, even as they find themselves critiquing medical authority. The lack of a radical agenda on the part of Fibro Spot participants is by no means a local phenomenon; it is not attributable to the actions of Fibro Spot participants in isolation of the larger political context. The political culture in 2005 is markedly less 21 radicalized than that of 1969 when the women’s health movement was born. Moreover, some aspects of the women’s health movement have been co-opted by profit-oriented medicine; for example, women’s health services are now big business and the medical provider industry sells “women’s-centered” health services, sans the radical impulses (Satel, 2000). The disjuncture between the goals of the women’s health movement and those of Fibro Spot also confirm what medical sociologists have predicted about contested illness movements, namely that they are not likely to develop politicized illness identities. “With illness characterized by diffuse symptoms, a politicized collective illness identity is more difficult to develop. … Activists are compelled to focus their energy and resources on gaining medical recognition” (Zavestoski, Morello-Frosch et al., 2004: 273). And so it is that we end with a paradox: participants at Fibro Spot mobilize to challenge medical orthodoxy only to demand that it frame their shared embodied experiences in strictly orthodox biomedical terms. Fibro Spot, like orthodox modern medicine, vigorously defends a conceptualization of illness and its origins as located within the individual, biological body. By mobilizing for medicalization, therefore, Fibro Spot participants obscure the ways in which fibromyalgia symptoms might be more than isolated biological entities. Neither the complex and overdetermined nature of women’s broadly felt distress, nor the social circumstances in which that distress is grounded and experienced, receive much attention at Fibro Spot. Whether or not we choose to label this “maladaptive illness behavior,” it is certainly a narrow and limited strategy for understanding and addressing women’s everyday suffering and its embodiment in symptoms of distress. 22 Asbring, P., & Narvanen, A.-L. (2003). Ideal versus reality: Physicians' perspectives on patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and fibromyalgia. Social Science and Medicine, 57(4), 711-720. Barker, K. (2005). The Fibromyalgia Story: Medical Authority and Women's Worlds of Pain. Philadelphia: Temple University Press (forthcoming). Barsky, A., & Borus, J. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 130(11), 910-921. Bohr, T. (1996). Problems with myofascial pain syndrome and fibromyalgia syndrome. Neurology, 46(3), 593-597. Brown, P., & Zavestoski, S. (2004). Social movements in health: an introduction. Sociology of Health and Illness, 26(6), 679-694. Brown, P., Zavestoski, S., McCormick, S., Linder, M., Mandelbaum, J., & Luebke, T. (2000). A gulf of difference: Disputes over Gulf War-related illnesses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(September), 235-257. Brown, P., Zavestoski, S., McCormick, S., Mayer, B., Morello-Frosch, R., & Altman, R. G. (2004). Embodied health movements: New approaches to social movements in health. Sociology of Health and Illness, 26(1), 50-80. Calderone, K. (1990). The influence of gender on the frequency of pain and sedative medication administered to postoperative patients. Sex Roles, 23, 713-725. Clarke, A., Mamo, L., Fishman, J. R., Shim, J. K., & Fosket, J. R. (2003). Biomedicalization: Technoscientific transformations of health, illness, and U.S. biomedicine. American Sociological Review, 68(2), 161-194. Clifford, J., & Marcus, G. E. (1986). Writing Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press. Conrad, P. (2005). The shifting engines of medicalization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 3-14. Crofford, L., & Clauw, D. (2002). Fibromyalgia: Where are we a decade after the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria were developed? Arthritis and Rheumatism, 46(5), 1136-1138. Denzin, N. (1987). Interpretative Ethnography: Ethnographic Practices for the 21st Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Dickerson, S. S., Flaig, D. M., & Kennedy, M. C. (2001). Therapeutic connection: help seeking on the Internet for persons with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Heart Lung, 55(2), 205-217. Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (1972). Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers. Old Westbury, NY: Feminist Press. Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (1973). Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness. New York: Feminist Press. 23 Eysenbach, G., & Till, J. E. (2001). Ethical issues in qualitative research on internet communities. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition), 323(7321), 1103-1105. Freidson, E. (1972). Professional Dominance. Chicago: Aldine. Goldenberg, D., Burckhardt, C., & Crofford, L. (2004). Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA, 292(19), 2388-2395. Hadler, N. M. (1999). Fibromyalgia: Could it Be In Your Mind? Rheuma21st. Retrieved February 15, 2001, from the World Wide Web: http://www.rheuma21st.com/archives/cutting_edge_fibromyalgia.html Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (1995). Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 2nd Edition. London: Routledge. Hardey, M. (1999). Doctor in the house: The Internet as a source of lay health knowledge and the challenge to expertise. Sociology of Health and Illness, 21(6), 820-835. Hardey, M. (2001). 'E-health': The Internet and the transformation of patients into consumers and producers of health knowledge. Information, Communication and Society, 4(3), 388-405. Henwood, F., Wyatt, S., Hart, A., & Smith, J. (2003). 'Ignorance is bliss sometimes': Constrains on the emergence of the 'informed patient' in the changing landscapes of health information. Sociology of Health and Illness, 25(6), 589-607. Hine, C. (2000). Virtual Ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Hoffmann, D. E., & Tarzian, A. J. (2001). The girl who cried pain: A bias against women in the treatment of pain. The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 29(1), 13-27. Illich, I. (1976). Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health. New York: Pantheon. Manu, P. (1998). Functional Somatic Syndromes: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Cembridge: Cambridge University Press. Martin, E. (1987). The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction. Boston: Beacon Press, 1987. Morgen, S. (2002). Into Our Own Hands: The Women's Health Movement in the United States, 1969-1990. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Ruzek, S. B. (1978). The Women's Health Movement: Feminist Alternatives to Medical Control. New York: Praeger Publishers. Satel, S. (2000). PC, M.D.: How Political Correctness is Corrupting Medicine. New York: Basic Books. Schneider, S. J., Walter, R., & O'Donnell, R. (1990). Computerized communications as a medium for behavioral smoking cessation treatment: Controlled evaluation. Computers in Human Behavior, 6, 141-151. Stimson, G. V. (1974). Obeying Doctor's Orders: A View from the Other Side. Social Science and Medicine, 8(2), 97-104. Stone, A. R. (1995). Sex and death among the disembodied. In S. L. Star (Ed.), The Cultures of Computing (pp. 243-255). Oxford: Blackwell. 24 WebMD. (2005). Fibromyalgia Support Group. WebMD. Retrieved July 1, 2005, 2005, from the World Wide Web: http://boards.webmd.com/topic.asp?topic_id=13 Wessley, S., Nimnuan, C., & Sharpe, M. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes: One or many? The Lancet, 354(9182), 936-939. Wolfe, F., Anderson, J., Harkness, D., Bennett, R., Caro, X., Goldenberg, D., Russell, I. J., & Yunus, M. (1997). Health status and disease severity in fibromyalgia: Results of a six-center longitudinal study. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 40(9), 15711579. Zavestoski, S., Brown, P., McCormick, S., Mayer, B., D'Ottavi, M., & Lucove, J. C. (2004). Patient activism and the struggle for diagonsis: Gulf War illnesses and other medically unexplained physical symptoms in the US. Social Science and Medicine, 58(1), 161-175. Zavestoski, S., Morello-Frosch, R., Brown, P., Mayer, B., McCormick, S., & Altman, R. G. (2004). Embodied health movements and challenges to the dominant epidemiological paradigm. Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change, 25, 253-278. 1 The research conducted by this collection of scholars primarily focuses on contested environmental illnesses, including accepted illnesses that have a contested environmental cause (Brown et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2004; Zavestoski, Brown et al., 2004; Zavestoski, Morello-Frosch et al., 2004). For example, one article (Brown et al., 2004) is based on interviews with activists in the environmental breast cancer movement, and is supplemented with observations at a research institute for the study of environmental causes of breast cancer. Although the environmental component of breast cancer is contested, breast cancer is not. As such, these activists don’t need to prove they are ill. Instead their grievances focus on medicine’s etiological accounts, treatment, and prevention of breast cancer. I question the usefulness of collapsing contested illnesses movements and movements for recognized diseases with contested environmental components into a shared category (i.e., “embodied health movements”) even though both types of movements use the body to challenge medical orthodoxy. While the latter may challenge medicalization in favour of politicizing the causes of their disease, the former is steadfastly committed to framing their suffering in strictly orthodox biomedical terms. In another paper these scholars themselves note that sufferers of contested illnesses are not likely to develop what they call “politicised collective illness identity” (Zavestoski, Morello-Frosch et al., 2004: 273) precisely because these “activists are compelled to focus their energy and resources on gaining medical recognition.” 2 Even with these safeguards, however, Eysenbach & Till (2001) claim that researchers should always seek informed consent from ESG participants. 3 Postings are presented verbatim. Because Fibro Spot participants frequently use ellipses in their postings, I use ‘[…]’ to denote places where I have omitted a section of 25 text from the original posting. Any text placed in ‘[ ]’ is text that I have altered from the original posting. 4 The postings used in this paper are examples of social threads. All the postings that connect to a particular thread of social interaction constitute a social thread. As such, the chain of postings is not necessarily presented as it appears on Fibro Spot. For example, there can be a message or messages between the postings as presented in this paper that are not a part of this particular social thread.