Essay Writing Tips - ENG 4UI with Ms. Kendall

advertisement

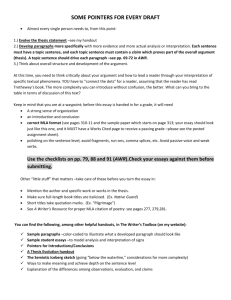

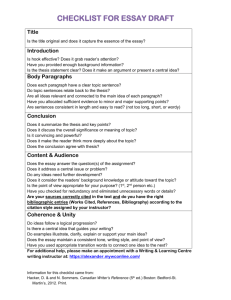

ENG4U: English, Grade 12, University Preparation Essay Writing Review Read the following review of essay writing tips. You have learned much of this content throughout your high school years, but it is always useful to brush up on your knowledge and understanding before embarking on the task of essay writing! Many students think writing an essay is a ‘by gosh and by golly’ exercise - or a ‘crap shoot’. Many people think the mark an essay receives lies in the hands of the teacher who evaluates it - whether they agree or disagree with the point of view. Nothing can be further from the truth. Most teachers have written and read a lot of essays. They know what a good essay looks like. Teachers are very well trained to assess essays objectively. In professional marking sessions, teachers who mark the same paper with the same rubric arrive at marks within a few percentage points of each other. This review is an attempt to de-mystify the essay process. It is hard to make it simple. There is no cut and dry recipe for essay success. Essays account for the largest part of marks earned in humanities courses. It is well worth your time to go through this guide and to use the strategies and tools provided in the resources package. Use the following tips to guide your essay composition in conjunction with the tools from the Orwell Unit. All information will support the successful completion of your Independent Study Essay, and all other essays in the term. What is an essay? An essay (the French: essayer = to try) is the ultimate self-directed academic exercise. Significant essay questions draw students into new understanding. That is what an essay is - a quest for new understanding; for insight through logical analysis; through the trial of an idea, concept, position (thesis). The logical analysis involves the application of the academic toolkit of the writer - knowledge, skills and concepts that the writer already has. Do Not Misunderstand: An ‘essay’ is not a repetition of information, or a research project. That would be a ‘research paper’ or sometimes a ‘report’. Literary essays are not papers on a topic. Essays lead to new understanding and insight - at least for the writer (and at higher levels, hopefully for the reader too). Therefore, let it be understood that essays are not written ‘on a topic’. Essays are written ‘on a question’. The classical inquiry questions always serve as handy tools to formulate the overall design and purpose of the essay. 1. 2. 3. 4. What (is being addressed)? How (is it being addressed / does it ‘work’)? Why (is it being addressed; to what end)? The over-riding question to be asking as you go is “So what?” Generating the Essay 1. Generate the essay questions to explore from the topic you were given. Essays are written ‘on a question’. When an essay ‘topic’ is presented as an assignment, the first very powerful, academic exercise is to establish the essay question. The question is the impetus for the essay and generates the thrust of the essay, which begins with the thesis. Introduction o o o o o The introduction states the thesis of the essay and its parameters (a narrowing in of when the thesis is true) The source of the question is alluded to (the topic / issue & its contexts) The introduction contains several sentences indicating what the path of argument will be. The introduction ends with a clear transition to the arguments of the essay. Writer’s Tip: Because a thesis subordinates itself to the parameters or conditions in which it is true, compound complex or at least complex sentences are most often used to express the thesis. Topic X generates questions, which results in an ‘answer’ that is a statement which can only be true within specific parameters. So: x = x (or x is true) when y and z are also true; furthermore, there is a relationship between x and y and z that will be demonstrated in a specific way (classification, cause and effect, compare and contrast etc.) So, if the topic is ‘symbolism in Golding’s Lord of the Flies’ there are various questions that can generate a thesis. For example: How does Golding systematically use symbolism in The Lord of the Flies to express or enhance the theme? (invites classification) OR How does Golding use symbolism to propel the plot and deliver the message of Lord of the Flies? (invites cause and effect) OR How can an appreciation of the sources of the symbolism Golding uses in Lord of the Flies help inform a reading of the novel? (invites compare and contrast) Checking the validity of your essay question: o The thesis that results does not merely restate the topic. o o o o The thesis that results does not merely state facts and summarize information. The thesis that results does not merely state a general opinion without stating supporting reasons. The thesis that results does not merely state the theme or thesis of the work being analyzed. The thesis that results is not stated in a confusing or pretentious way. Writer’s Tip: It may not be possible to judge on these criteria until the essay has been written once. 2. A pattern of argument should be selected and filled in, in response to the thesis question. The pattern of argument used must fit the thesis question. Sometimes a first draft has to be written using ‘free-writing’ (also called a ‘discovery’ or ‘writing to learn’ draft) before a structure can be decided on. Sometimes the structure is prescribed in the assignment. The following argument outline should be loosely adhered to regardless of the structure. Controlling Idea statement - state the purpose of the paragraph; the argument being used to support the thesis; Focusing statement - state what the parameters of this argument are; Major Support - the chief support of the controlling Idea Explain the argument and how it supports the thesis; Support Details - Proof, description or citation of evidence that this argument is true; Statement of how this proof proves the argument true; SO what? “So how does this all fit together and further my thesis?” Transition to next argument. A conclusion paragraph sums up the arguments; gives a persuasive push to the logic of the argument. The conclusion demonstrates explicitly how the thesis has been ‘unpacked’. The thesis question should be used by the writer to focus the conclusion. This is done by establishing a relationship between the thesis question and the arguments in the conclusion of the essay. Do Not Misunderstand: It is a misconception that the conclusion merely ‘restates’ the thesis. It is an oversimplification taught at the elementary stages of the essay writer’s education. This constitutes the basic structure and content of the essay. If the above criteria are met, if the essay indicates a thorough understanding of the material being regarded, and if a minimum of errors are made, the essay will warrant 50% of allotted marks. Do Not Misunderstand: When the essay is initially taught in Grade 9 and 10, students may be led to believe that each argument is limited to one paragraph. In more sophisticated essays this is not at all true. Any one of these stages of argument may take up one paragraph by themselves. Any combination is possible. Revising the Essay Do Not Misunderstand: Revision does not refer to ‘proof-reading’; it refers to a reconstruction, executed with reason and good judgment. The first draft is a ‘write to learn’ draft. The second, third and fourth revisions are the ‘crafting’ of the essay. 1. Correlate the thesis to the actual arguments. The thesis should contain, explicitly, the parameters of the arguments. Arguments should be arranged in ascending order from the most obvious, to the most complex. The most complex are usually those that require a thorough understanding of the most obvious arguments to be appreciated by the reader. 2. Revise and reinforce arguments and substantiation Writer’s Tip: At this point the writer may have gained some new insights (through writing) that make some of the statements in the essay too obvious or perhaps irrelevant. The insights gained through writing may have shifted some of the initial arguments, or even the thesis. Conversely, the writer may have made too many leaps. The concept of ‘unpacking’ complex arguments may help direct and clarify the arguments. Check that the citations and proofs are the most powerful possible. If it is difficult to substantiate arguments with powerful evidence, question the arguments; or break the arguments and evidence down (unpack them further) to build them logically for the reader. Check the escalation of arguments against recommended essay patterns (climactic order). Check transitions. Check for logical unity and flow. Revise the introduction and conclusion. Aim for clarity and a powerful persuasive voice. This constitutes the form of the essay. The essay will warrant 75-85% of allotted marks if there is a logical escalation of argument, the arguments are well substantiated, the essay indicates a thorough understanding of the material being regarded, and a minimum of rhetorical and structural mistakes have been made. Polishing the Essay up to 100% An ‘A’ essay has a definite, strong, persuasive VOICE and STYLE. What is VOICE? VOICE refers to both the inner ‘sound’ of the writing, and credibility. VOICE is best cultivated through copious reading. It is difficult to define, but easy to identify. Good writing is seamless. There would be no jerky, unnatural stumbles in reading aloud. There would be few confusions and pauses by the reader to pursue ‘gaps’; the essay ‘washes’ over the reader. Writer’s Tip: Read essay aloud (to a mirror, a friend, a tape); nothing improves voice more rapidly than reading aloud. With highlighter in hand, read. Whenever the tongue falters, highlight. Whenever you inner ear hears a shift in tone or credibility in voice, highlight. Plan to revise those parts. Best tangible checks: Level of language is uniform; (style) Purpose of language is uniform, but there is variety as well as unity; (style) Verb voice is consistent - active or passive; passive is better for persuasive essays; Point of view is clear and uniform; Variety of sentence structures, usually with a ‘run, walk, run walk’ rhythm; (style) Parallel structure: words, phrases, clauses should be parallel when strung together. Sentences and even paragraphs can be parallel to help create emphasis; (style) In an essay, the ‘subjective’ does not emerge as an independent voice or ‘critic’. VOICE constitutes the ‘WOW’ of an essay. To improve voice, READ. VOICE may be enhanced through the following strategies. Diction - keep language simple, direct and authentic (you have to write with your own ‘voice’ of conviction to create a strong voice - if you are uncertain, stop, work out your ‘problem’) Do not use ‘flowery’ language. This is the most common characteristic of ‘essay gone wrong’. Train you r inner ear. Read your work to the mirror. If it doesn’t sound like ‘you’ - ALERT. Rewrite your work until you can read it easily with your own authentic and recognizable voice. Syntax - syntax is the most important and least understood element of voice. In essays complex ideas are arranged so that one idea often is (needs top be) subordinated to another, or built upon another. It becomes difficult to knit ideas together in logical hierarchical order, and the connections and transitions become problematic. Clear thinking leads to clear syntax. Once again - the success of the voice lies in a sound and thorough grasp on the ideas of the essay. Syntax refers to things like transitive conjunctions and parallel structure between words and phrases. Essays that lack these are difficult to follow - and ‘voice’ is instantly compromised. Sentence Structure - Vary sentence structure in natural ways. The reader should be able to hear a voice with emphases and pauses in their inner ear as they read. Falls or rushes and pauses should be balanced so the essay flows; so the reader has opportunities to gather the thought and follow the argument. Essays with long words in complex arrangements are sometimes inevitable – in which cases writers should pay particular attention to the stylistic strategies that create flow. See the MLA style guide. Writer’s Tip: One quick fix tactic that may work, is to read some good essays, then dip back into the draft under construction, and emulate the voices and the strategies for transitioning between ideas you encounter. Use the rubric by which your essay will be marked to double check your essay before submitting it. See your “Kiss of Death” sheet to remind yourself of the errors that are unacceptable in a 4U paper. Repair Shop! Students who repeatedly have difficulty with, or fail at essay writing, read on. There are several reasons for failure. The major reasons are: Lack of understanding of cause and effect in real terms: ie: Lack of understanding of the cause and effect relationship between unclear thinking and unclear writing; or lack of understanding between the cause and effect relationship between procrastination and insufficient time to complete all the stages of revision once the process is actually begun. o Lack of clarity is a result of a lack of understanding of material/topic; o Lack of clarity is a result of the convoluted thinking which results from confusion o Lack of clarity is a result of an inability too read logically; SOLUTION: Study material thoroughly. 4. Communicate with others, ask/quest into the issues and source materials. 5. Use the inquiry model to systematically attack for understanding. 6. Leave plenty of time to research or reflect on questions that result from the recognition of confusion. 7. Leave lots of time for revision. Ignorance of grammar; o Ignorance of the basics - incorrect spelling; parts of speech; noun/verb agreement; punctuation o Ignorance of sentence structure - lack of parallelism in phrases, clauses; parallelism of argument etc; incorrect use of colons, semi-colons, commas (no CONTROL over writing) SOLUTION Learn grammar Dig up old essays or papers, investigate every error with the aid of a grammar manual. Use the error tracker if you lose out on marks repeatedly because of spelling and grammar errors. Some suggestions for overcoming Essay Writing weaknesses : 1. Do not procrastinate; process and revision are the key to success; 2. Begin by stating a thesis question, rather than by devising a thesis. Then shape a thesis in such a way that it will lead to an essay in a definite pattern of argument. 3. Make a rough outline for the essay, following the chosen pattern of argument. 4. Check your outline to see that you haven’t actually changed the parameters or thesis, even though you stayed on the right topic. If you have made this common error, select ONE of these outline theses and try to build a new outline around it alone. Experienced teachers agree weak essays are general and superficial discussions of a topic, rather than a quest for deep understanding. 5. NOW, establish an essay question and a thesis, and adjust the outline. 6. Follow one pattern of argument, and the paragraph structure suggested above verbatim. Create a template to be filled in point form. Work to fulfill each individual component of each paragraph. If you typically have difficulty writing fluidly include steps seven through ten. 7. Free write each paragraph. 8. Write each paragraph out in simple sentences. 9. Re-order arguments logically where necessary; arrange paragraphs so arguments escalate - unpack logically. 10. Join some of the sentence together to form complex, compound and compound complex sentences. 11. Check that each proof is interpreted correctly as logical proof of the argument. 12. Ensure all ‘so what?’ statements are well constructed and logical. 13. Work on transitions between paragraphs. 14. Read essay onto tape or into mirror. 15. Focus on voice. 16. Proofread essay