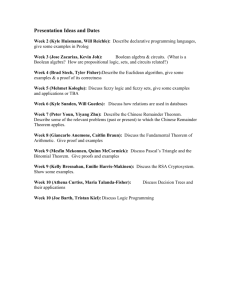

Filling in the Folk Theorem

advertisement

Filling in the Folk Theorem: The Role of Gradualism and Legalization in

International Cooperation to Combat Corruption

Kenneth W. Abbott

Northwestern University School of Law

k-abbott@northwestern.edu

Duncan Snidal

University of Chicago

snidal@uchicago.edu

DRAFT

Comments Appreciated

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

Filling in the Folk Theorem: The Role of Gradualism and Legalization in

International Cooperation to Combat Corruption

Cooperation theory tells us much about the possibility of cooperation, but surprisingly

little about how we actually get to cooperation.1 Given the circumstances of an issue, the

theory identifies the outcomes that can be sustained by the parties (i.e., possible

equilibria). Those that make the parties better off than alternative equilibria, especially

the status quo ante, represent “cooperative” outcomes. Cooperation theory further

analyzes how contextual or institutional changes — such as increasing time horizons and

issue linkage, or decreasing uncertainty and membership — create new cooperative

equilibria or make existing ones more stable. But the actual attainment or transition to

any particular cooperative outcome remains an article of faith that “If there is a

cooperative equilibrium, states will find it.” It is a “big bang” theory of cooperation

which presumes that cooperation will suddenly occur without offering any account of its

development.

This big bang approach does not correspond to what might be called the “natural history”

of cooperation. Most real international problems have persisted for a significant period of

time before cooperation occurs, sometimes including a period during which the

possibility of beneficial cooperation was not even recognized. Examples include the

development of various types of international economic cooperation in the twentieth

century, on-going efforts to promote cooperation on international health and human

rights, and the corruption problem we analyze below. Alternatively, even when a

problem emerges precipitously — perhaps due to a new technology like MIRV missiles

or a relatively sudden change in circumstances such as global warming — actors need to

time to determine cooperative solutions and resolve the host of difficult problems of

getting to them. Consequently, cooperation is more typically attained either through a

series of smaller steps and/or through on-going processes of negotiation rather than

through a big bang.

This paper develops an analysis of gradualism, and specifically gradualism through

legalization, as a way to understand the development of international cooperation.

Gradualism – by which we mean breaking cooperation into a series of steps — is

valuable because it addresses the series of problems that make big bang cooperation

difficult. It provides a means for actors to learn about an issue in both a technological and

normative respects, and to reduce uncertainty about the issue and the goals of the actors.

Gradualism further provides a setting to address the bargaining and distribution problems

that make cooperation difficult, and to select or develop a focal point for cooperation.

Equally important, it provides a way to counteract the significance of the status quo as a

compelling but noncooperative focal point. Finally, gradualism helps to create the

1

By “cooperation theory” we mean the body of results drawn from game theory that undergirds

“liberal institutionalist” international relations theory. These results were first used to

demonstrate the possibility of decentralized cooperation in anarchy and, more recently, to analyze

the role of institutions and norms in international politics.

1

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

common expectations need to overcome the Assurance problem which makes the

transition to an agreed equilibrium difficult. For these reasons, actors often can achieve a

gradual approach through legalization even when big bang cooperation would fail.

We focus on legalization because it is the prevalent form of gradualism in international

relations today.2 International legalization refers to a set of rules, norms, institutions and

practices that shape the expectations and interactions of international actors (Abbott et. al.

2000). As such, it provides a framework of accepted behaviors and procedures within

which actors are able to explore and establish new cooperative arrangements. However,

the legalized framework varies substantially across different areas — from “hard”

legalized arrangements with precise rules, high obligation and significant delegation to

“soft” arrangements that are relatively low on all these dimensions (Abbott and Snidal

2000) — and the success of gradualism in an issue may depend on the form of

legalization. Sometimes the applicable legalized arrangement is predetermined by prior

cooperative agreements for how certain problems will be handled (e.g., global trade

issues are handled through the WTO),but in many cases actors have some latitude in

choosing a legalized arrangement that will be more effective for the cooperation problem

they seek to solve (forum-shopping). Whether the choice of legalized process is

exogenous or endogenous, it plays an important role in determining whether actors will

achieve cooperative agreements.3

The process of legalized cooperation is often mixed with the creation of new rules that

change the legalization in an issue area. Any legalized solution to a cooperation problem

requires working out an agreement within the pre-existing rule and procedures, which

may strengthen or elaborate those rules. But since much of international relations is thinly

legalized, international cooperation sometimes takes the form of articulating new legal

arrangements, or substantial “hardening” of existing soft legalization. Here the gradual

aspects of cooperation are often reflected in slow, stepwise movements to higher levels of

legalization.4 We thus use legalization in an expansive sense to include both processes

of cooperation that operate within the prevailing level of legalization and cooperation that

creates new rules to augment existing ones.

To demonstrate the importance of gradualism and legalization we analyze international

efforts to combat corruption, with an emphasis on the development of the 1997 OECD

2

For a discussion of legalization see Abbott at. al.(2000). This concept of legalization is very

broad so that the interesting questions are not about whether particular international issues are

legalized but why various areas are legalized to different extents and in different ways (Abbott

and Snidal 2000). We do not discuss the details of legalization here, but build on that prior

analysis.

3

Thus we do not claim that gradual or legal processes will always succeed. See Abbott and

Snidal (2002a) for a discussion of why the WTO was unable to take effective action on bribery

because it was too legalized.

4

In a thin legal environment we are probably more likely to see increases in legalization to

promote cooperation, but “delegalization” may be more conducive to cooperation in other cases.

This corresponds to the general point that “more is not always better” with respect to international

legalization, and softer legalization may be preferable to harder legalization for solving some

problems.

2

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

“International Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in

International Business Transactions” (Anti-Bribery Convention). This Convention

emerged through a gradual and legalized process that overcame a number of difficulties

that had foiled earlier big bang efforts against foreign bribery by multinational firms. In

brief, a legalized process through the OECD offered a setting where states could learn

about the problem of corruption, reduce their uncertainty, change their positions, craft a

series of steps towards a cooperative agreement and resolve their assurance problems. It

established a new set of legal rules to govern international bribery and a fairly minimal

institutional apparatus that promoted the cooperative transition and is currently

overseeing the implementation of the agreement.

In summary, our analysis deepens the understanding of how international cooperation

occurs by marrying an analysis of gradualism through legalized processes to the existing,

more structural theory of cooperation. The next section discusses how the structural bias

in international relations theory makes it hard to understand processes of change and

cooperation. We focus on liberal institutionalist theory which uses the “folk theorem” to

establish the possibility of cooperation and to provide insight on its institutional and other

requisites. But the folk theorem offers no explanation of how cooperation occurs.

Indeed, we argue that its best prediction is that cooperation will not occur. Therefore we

“invert” the folk theorem to emphasize the inter-related problems of bargaining and

distribution, uncertainty and Assurance that make cooperation problematic. The third

section discusses how gradualism helps actors overcome these difficulties and in

particular, why legalization often provides a “focal process” through which states pursue

cooperative possibilities. The fourth section of the paper offers a detailed empirical

examination of how cooperation failures in the preventing transnational bribery were

overcome by shifting to a gradual legal approach.

I. The Limits of Cooperation Theory

Although our analysis focuses on the limits of liberal institutional explanations of the

transition to cooperation, this shortcoming is connected to the structural bias of

international relations theory. Our fundamental critique is that cooperation theory is too

structural in focusing on how the prevailing configuration (including preferences,

capabilities, ideas and institutions) determines equilibrium outcomes without paying

attention to the processes by which particular equilibria are attained. Before turning to

our critique liberal cooperation theory, it is worth briefly mentioning that this general

limitation is shared by the other major international relations theoretical approaches.5

Neorealism takes pride in being a structural theory, partly because it is a theory of stasis

that sees anarchy as enduring. To be sure neorealism includes mechanisms of adjustment

such as warfare and alliance formation, but these are means of adjusting to a structurally

determined outcome resulting from exogenous changes in the distribution of capability.

5

This critique applies to systemically-oriented theories. A number of approaches ranging from

decision-making to crisis bargaining to recent analysis of transnational movements are attentive

to processes, although they typically aren’t well-connected to systemic theory. The challenge we

address is that of connecting structural and process theories.

3

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

There is no sense of possibility whereby actors might choose alternative outcomes within

a given anarchic setting, but simply an argument that circumstances drive actors to a

particular outcome.

By contrast, constructivism strongly embraces the possibility of change -- anarchy, after

all, is what states make of it -- but it too has a structural side that severely limits change.

Although its view of outcomes as heavily shaped by ideas suggests a fluidity that is

amenable to change, ideas are not just enabling but also constraining. With respect to

collective outcomes, the distribution of ideas can be as significant a structural constraint

as is the distribution of capability or material interests. Moreover, many of the central

mechanisms invoked by constructivists — including habit, the logic of appropriateness

and socialization — are backward-looking; they therefore provide better explanations of

continuity than of change. Other mechanisms — including persuasion and deliberation

— are more amenable to explaining change but the literature remains at an early stage in

explaining how these work in international relations.

To address what we see as a shared problem in international relations theory, we draw

insights from both of these perspectives in studying the transition to cooperation. Realism

is valuable for its critique of cooperation and, especially, for its emphasis on the

Assurance problem that makes transition to cooperation difficult. Constructivism is

useful because of its emphasis on the possibility of change and the need to pay attention

to the processes and actors underlying structural theory. A special attraction of

examining legalization as a key process of cooperation is that legalization involves both

normative and rationalist elements and so builds on the complementarity of constructivist

and rationalist arguments. In this spirit, we move to a detailed analysis of the limits of

the liberal cooperation theory.

“Big Bang" Cooperation in the Folk Theorem

The folk theorem is the centerpiece game theoretic result underlying the contemporary

theory of international cooperation and institutions. It is actually a family of results

showing that any feasible cooperative outcome — that is, one that is technologically

possible and that benefits all parties over time — can be sustained as a decentralized

equilibrium provided the actors all care sufficiently about the future and have sufficiently

high-quality information about their circumstances.6 Its basic logic is that parties

conditionally cooperate with one another while being prepared to punish noncooperators

sufficiently to ensure that no one will be tempted to break out of the arrangement and free

ride on others’ cooperation. In terms of the familiar Prisoners’ Dilemma (PD) problem,

6 It is a folk theorem because the basic intuition has been long understood; it is a folk theorem

because it has been shown mathematically. The mathematics entail considerably more than

formalistic window-dressing and has opened up a much deeper understanding of the precise

conditions under which the arguments applies — and its limitations which we examine below.

The resulting family of folk theorems continues to grow as its application in specific

circumstances is refined. For example, Kandori (2002) examines the significant implications of

private versus public monitoring where the assumption of common information about actions

does not hold.

4

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

for example, the folk theorem asserts that outcomes that are preferred by both parties to

the mutual noncooperation outcome often can be maintained through reciprocal strategies

such as “Tit for Tat” or “Grim Trigger.”

Figure 1 shows the single-play “stage” game of PD with its unique equilibrium outcome

at the {2, 2} payoff, which is suboptimal compared to the {3, 3} payoff. Figure 2 shows

the folk theorem result for the corresponding repeated PD game where any outcome in

the shaded area can be supported by decentralized enforcement when actors care

sufficiently about the future. Importantly, the theorem is not restricted to repeated

Prisoners’ Dilemma or to bilateral interactions. It applies to any circumstance where

actors can realize joint cooperative gains over time.7

___________________

Insert Figures 1, 2 Here

___________________

The folk theorem is a possibility theorem. It does not demonstrate that some high or even

moderate level of cooperation will necessarily occur, but only that it is feasible. Indeed,

noncooperation (e.g., repeated play of the {2, 2} Nash equilibrium of the stage game)

always remains a possible equilibrium outcome. Moreover, as a comparative statics

result, the folk theorem neither explains how a move to a superior cooperative

equilibrium might come about nor provides any clear justification for the common

implication that it will come about. As we argue below, in international relations, where

actors often begin from the noncooperative outcome implied by international anarchy, the

best prediction from the folk theorem alone is a probably that they will stay there.

The basic folk theorem logic extends to more difficult circumstances that correspond

more closely to those of international politics. Even if actors cannot fully monitor each

others’ behavior, for example, cooperation can be maintained through appropriate

modifications of actor strategies, as by ignoring small deviations but punishing large ones

severely (Downs and Rocke, 1995). Similarly, escape clauses enable trade treaties to

sustain cooperative outcomes by granting parties temporary flexibility to respond to

potentially disruptive shocks such as domestic crises (Milner and Rosendorff, 2001),

while monitoring institutions can improve the performance of security arrangements

when the motivations of other actors are unclear (Kydd, 2001). Such adaptations

demonstrate that more complicated arrangements can support decentralized cooperation

under more difficult circumstances, but they do not explain how such arrangements can

be implemented in practice. Indeed, these increasingly complicated remedies suggest the

inadequacy of the strictly decentralized cooperation embodied in the folk theorem.

7

The shaded area in Figure 2 represents average undiscounted payoffs in the repeated game.

Uncertainty or diminished concern for the future reduces the range of equilibria that can be

supported until, at some point, the possibility of supporting any cooperative outcomes is

eliminated. Finally, we do not address important issues such as subgame perfection or

renegotiation since our interest is not in the refinements that game theory is capable of but rather

in the gaps that it contains.

5

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

Cooperation may need to be more institutionalized to address the actual conditions that

actors face in international relations, both to expand the range of feasible outcomes

(Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal, 2001) and to help states achieve them.

In sum, the folk theorem is a structural theory that describes the alternative possibilities

in a particular setting and suggests the arrangements needed to support them, but does not

directly address how actors can expand those possibilities or actually get to a cooperative

outcome. For our purposes, then, it is more fruitful to invert the folk theorem,

emphasizing its “limitations.” Here we identify a number of impediments to international

cooperation revealed by the theorem: problems of coordination, distribution and

bargaining posed by multiple equilibria, and several distinct problems of uncertainty. In

the following section, we consider how processes of cooperation allow actors to address

these impediments.

Multiple equilibria

One well-known problem illuminated by the Folk Theorem is that of multiple equilibria

— that is, a multitude of possible outcomes can be supported by decentralized strategies.

In Figure 2, for example, the shaded area offers an infinitude of equilibria, but the theory

offers no compelling analysis of how one particular equilibrium is selected or, especially,

how a “good” equilibrium might be attained. Economists sometimes assume that

outcomes will be restricted to efficient (Pareto optimal) points; but they provide no nontautologous warrant for an assertion that fails empirical scrutiny, at least in the domain of

international politics.8 Moreover, even the efficiency presumption leaves open all the

possible outcomes along the dark line in Figure 2 (the points on the Pareto frontier that

make both sides better off compared to the status quo ante). Additional criteria such as

“symmetry” or “fairness” might further narrow equilibrium selection in highly simplified

theoretical settings, but these offer little guidance in real world settings where symmetry

and fairness are neither well-defined nor necessarily compelling motivations to the actors.

More generally, the lessons of strictly formalistic attempts to determine “unique”

equilibria in strategic interactions — including both the Nash refinement program for

noncooperative games and the solution theory of cooperative games —indicate that more

precise and general predictions are unlikely to emerge from the game model alone.9

Rather than representing a shortcoming of the folk theorem, however, the presence of

multiple equilibria reveals a fundamental feature of the world and its politics. Without

multiple equilibria, there would be no politics, in the sense that outcomes would be

determined uniquely in terms of the technology of the problem and the interests, and

8

The efficiency view arises from the “market” presumption that if there are joint gains to be

made then actors will have an incentive to achieve them. This depends on having the appropriate

institutional and informational arrangements, which applies rarely in real economic problems and

less often in political ones. The efficiency view can be tautologously restored by treating

institutions and information as constraints and costs. Although that does not advance the analysis

per se, it may have some methodological purchase (Townsend 1988; Snidal 1996).

9

Schelling 1960. The theory of the core is probably the most compelling refinement program. In

special institutional circumstances such as the perfectly competitive market it produces a unique

equilibrium but, more generally, the core may contain a multitude of equilibria or none at all.

6

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

beliefs of the actors. In such a world, there would be no role for cooperation because

change would be driven solely by shifts in exogenous factors.10 With multiple equilibria,

however, there is room for contestation (including leadership, bargaining, coalitionbuilding and persuasion) and cooperation (including learning and deliberation), and for

possibilities of contingency and path dependency, that fundamentally change the nature

of international politics. Movement from anarchy to cooperation, or from one level of

cooperation to another, becomes possible. While the folk theorem does not directly

address these processes, it indirectly reveals their significance.

a. Coordination. The selection of a particular equilibrium among many is usually

explained in terms of the existence of a focal point — a particularly salient outcome that

somehow commands the attention of the players so that they coordinate their actions

around it. However, there is no good theory of focal points within game models

(Morrow, 1994), and analysts need to beware focal points that are artificially induced by

the model itself. In Figure 1, for example, the symmetry of the game and the

specification of a single dichotomous choice for each party —and therefore of a unique

point of bilateral cooperation — make coordination on the {3, 3} payoff seem compelling

if the game is repeated. This is carried over into the folk theorem representation of

Figure 2, where the corresponding kink in the Pareto frontier might suggest a compelling

point of cooperation. However, this focal point is an artifact of the model and disappears

when actors have more continuous choices, as in most real-world problems, so that

“cooperation” is not uniquely defined and the problem is not strictly symmetric.

Although game theory ultimately may provide a more systematic understanding of focal

points, at present we must rely on empirical knowledge of particular settings, combined

with auxiliary theories of behavior, for guidance.11

An even greater challenge to cooperation is that, in many real international problems, the

most compelling focal point is the status quo, in which actors are not cooperating.

Whereas the folk theorem adopts an Archimedean perspective, identifying possible

equilibria from outside the game, most cooperation problems occur among actors who are

already coexisting at a bad equilibrium. Players in such a game already have had their

expectations formed by a history of noncooperation. Transition to cooperation thus

requires not only creating a new focal point, but also eliminating the noncooperative

status quo focal point in both its psychological and material manifestations. In this

respect, the folk theorem significantly understates the difficulty of cooperation, and

especially of moving to greater cooperation, where patterns of behavior are already set.

10

This world corresponds fairly closely to the Realist view of anarchy as tragedy, where states

play out a script determined by the distribution of power but cannot change the plot. The liberal

(and constructivist) critiques of realism begin with the observation that the anarchy script does

not rule out multiple equilibria (different possibilities) and therefore allows the actors to change

the plot by finding paths (of different kinds) to new equilibria. Here we argue that, although

cooperation theory has identified the possibility of different endings to the story, it provides an

inadequate account of the plotlines.

11

For empirical work in an experimental mode see Crawford (2002). For a discussion of

auxiliary theories see Ferejohn and ***. Myerson (1991) has an interesting discussion of the

difficulties of modeling these processes

7

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

b. Distribution and Bargaining. Choosing among multiple equilibria further raises

issues of distribution and bargaining, which lie at the heart of politics. Actors who agree

on the desirability of getting to the Pareto frontier still have strongly opposed interests in

selecting a specific efficient point on the frontier (Krasner 1991). The resulting costs of

delay and bargaining also create inefficiencies. Indeed, Fearon (1998) makes the

compelling point that even as a lengthy shadow of the future enables decentralized

enforcement of cooperative outcomes, it simultaneously enhances ex ante incentives for

distributive bargaining that inhibit efficiency. Institutional solutions such as linkage

across issues (Mitchell and Keilbach, 2002) or periodic renegotiation of limited-duration

agreements (Koremenos, 2001) again may help reconcile these conflicting tendencies.

However, such considerations also suggest again that getting to cooperation will entail

intermediate steps of bargaining and institutionalization that the folk theorem does not

address.

The problem of choosing among equilibria may be more severe when large

numbers of states are involved. The collective action problem means that even if there

are joint gains to cooperation, there will incentives to free ride in the hope that others will

bear the costs of organizing cooperative arrangements. Conversely, whatever the

decisional mechanism for agreement, actors will have incentives to make strategic

proposals that create decisional cycles, which make reaching agreement all that more

difficult. Such difficulties suggest an important role for entrepreneurship and leadership

in guiding states towards an agreeable cooperative outcome.

Uncertainty Problems

Bargaining problems also point towards the strong assumptions about information (e.g.,

what the actors must know about their interaction and about each other) that underlie the

application of the folk theorem. While the theorem can be adapted to accommodate

various types of uncertainty, such considerations nevertheless impair the effectiveness of

decentralized cooperation and pose additional impediments to moving to higher levels of

cooperation.12

a. First, actors may have technological uncertainty because they do not know

enough about the state of the world and therefore about the full consequences of the

actions proposed. Indeed, actors may not understand the problem well enough to identify

all the actions that are possible. In these circumstances, even if all the parties see some

level of cooperation as beneficial, they may be unsure how far they can or wish to go in

the cooperative direction. In terms of Figure 2, there is uncertainty as to the location and

shape of the Pareto frontier. This complication can be accommodated formally by using

expected values in the folk theorem -- provided that the probability distribution of

possible outcomes for each combination of actions is known (Fudenberg and Maskin

12

Koremenos, Lipson and Snidal (2001) discuss how different types of uncertainty — over

behavior, over preferences and over the state of the world — impair cooperation and how these

can be overcome by appropriate institutional design. Their focus is on how uncertainty impairs

the operation of agreements whereas we focus here on the related but different issue of how

uncertainty inhibits actors from getting to agreements.

8

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

1986).13 But this approach is problematic for complex problems such as global warming

or issues involving technological change. In these cases, uncertainty cannot be reduced

to “risk” since actors cannot specify all the possible actions and their consequences, let

alone their probability distribution.14 This obviously makes selecting an equilibrium very

difficult. Moreover, such situations will be heavily contested politically because

ambiguity aggravates the impact of risk-aversion.15 Actors will raise the specter of “worst

case” scenarios (on either side of the issue) as a bargaining tactic, blurring the situation

further.

b. Second, preference uncertainty arises when actors are unsure of others’

incentives and/or capacities.16 Even if other states appear to support moves to more

cooperative equilibria, they may not be sincere, may not want to cooperate to the same

extent, or may be unable to cooperate. Actors with a low value for cooperation or with a

weak capacity (political or technological) to implement cooperative agreements might

nevertheless agree to a proposal for a high level of cooperation because it would offer

them an opportunity to free ride. Alternatively, actors with a high value for cooperation

might feign disinterest for reasons of bargaining. This type of uncertainty makes

selecting an efficient equilibrium extremely difficult. It is especially significant for

applications of the folk theorem to international relations, since states are not truly

unitary actors as typically assumed. Instead, a state’s “preferences” and capacities are

subject to the interplay and uncertainties of domestic politics, where supporters and

opponents of a proposed policy contest its acceptance and implementation in ways that

often are not transparent to other states.

A related type of uncertainty occurs when actors are unsure of their own preferences and

capacities, especially for new and unfamiliar problems. This type of uncertainty is

typically ruled out in rational models with unitary actors, although introspection suggests

that it may be significant, at least for fundamentally new problems like cloning.17

13

Alternatively, the probability distribution can be over different types of actors whose costs and

benefits are known. A state’s uncertainty about its own preferences could even be represented

this way where the different types correspond to (say) the types of electorate it is likely to face in

the next election. These cases correspond to different types of uncertainty discussed below. Note

that while the cases are formally similar, they differ sharply in terms of their substantive

interpretation and possible institutional remedies.

14

One way to analyze this problem within the standard framework is to specify it as a prior game

where actors decide how much search effort to expend to reduce this uncertainty. The difficulty

with this approach is that this prior game is itself difficult to specify — how much effort does it

take to discover what we don’t know is even there? — and effectively asks the actors to solve a

more difficult problem than the first one which they already cannot solve. For efforts to analyze

problems of “bounded rationality” in game frameworks see Fudenberg and Levine (1998).

15

Strictly speaking, this is not risk aversion in the economist’s sense since, as noted above, the

problem cannot be specified in terms of probability distributions. An emerging literature has

begun to analyze this problem in terms of “ambiguity-aversion.” See Ellsberg (1963) and ***.

16

Watson (1999).

17

This is especially true if we allow the possibility of preference change or are considering

preferences over new things. For example, if I don’t know if like a new food is it because I don’t

know what it tastes like or, never having tasted it, I don’t know my taste for it? Especially if

9

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

Regardless, uncertainty about one’s own preferences is of central importance when the

principal actors, like states, are composites whose “preferences” are complex

aggregations of the interests and values of underlying actors, and which can often

implement agreements only by coordinating the responses of domestic actors. In

principle, it may be desirable to handle this problem theoretically by modeling the

underlying actors directly — unfortunately, this requires a theory of domestic politics and

action. In practice, therefore, it may be more promising to analyze the problem

empirically in terms of aggregate actors partially engaged in discovering their preferences

and capacities (i.e., their domestic political constraints) through the process of

cooperation. When leaders do not know how an international policy will play

domestically, they take this uncertainty into account in negotiating and constructing

agreements.18

The uncertainties discussed above may operate somewhat differently when actors are

already in equilibrium. They feel no pressure to change their behavior (by definition) and

know that others feel no such pressure. Moreover, experience at equilibrium offers no

way to learn about alternative outcomes, about others’ preferences for change, or about

their own preference for change. Finally, insofar as equilibrium implies a certain type of

contentment, it is not conducive to promoting learning that a superior equilibrium exists

and pushing states to adopt the necessary changes. Uncertainty blends into ignorance.

c. The third and greatest challenge to the application of the folk theorem arises

from uncertainty over which equilibrium has been chosen and thus what actions everyone

will (and therefore should) take. A shared “common conjecture” about how everyone will

behave is necessary to support the realization of an equilibrium. Even when there is a

unique efficient equilibrium, it may be difficult to develop the necessary expectations to

ensure that it will come about. The most famous example is the Assurance Problem (or

Stag Hunt or Security Dilemma game) where cooperation is not guaranteed even with

communication among the players. Even a small amount of doubt as to whether the

others will cooperate will lead one not to cooperate; the possibility that one may hold

such doubt makes the others’ noncooperation reasonable; and so forth. The result is that

everyone chooses not to cooperate because of the difficulty in sustaining the expectations

necessary to support an outcome that all recognize as superior. (The small level of doubt

necessary to upset this conjecture is very plausible given the other uncertainties discussed

earlier.) Preplay communication cannot readily resolve these doubts because actors

always have an incentive to say they will cooperate even when they intend to defect or

lack the capacity to cooperate. So arriving at a common conjecture to support an

equilibrium is difficult even when the “best” equilibrium is “obvious.”

tastes relevant to new issues have to be acquired or discovered, at some point they must be

unknown. Thus policy debates over issues like cloning and ozone depletion involve not only

differences among preferences but also deliberations over what should be our preferences.

Finally, if the equilibrium chosen shapes preferences, then choosing equilibria is not separate

from choosing tastes over time.

18

A variation of this is that leaders may be forming domestic preferences – as when their

policies help define other states as enemies or friends.

10

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

The more general and difficult question concerns the source of the common conjecture in

the first place. Only in special cases can it emerge solely from the game itself, as when a

game is dominance solvable (by iterated deletion of dominated strategies), and even these

cases are subject to challenge. For example, dominance solvability becomes less

compelling (both theoretically and empirically) as more rounds of iteration are required,

because of the onerous requirements it puts on the actors. Similarly, a common

conjecture on a single efficient equilibrium is problematic when risk and efficiency

considerations point in different directions (as in Assurance). Of course, when interests

are identical or highly correlated, a minimal process of pregame communication (cheap

talk) may suffice to establish a common conjecture. But the folk theorem suggests that

there will often be a wide range of equilibria that create distributional differences and

assurance problems. In this more general case, although every outcome can be supported

by some set of beliefs, there are not purely theoretical grounds to suggest that actors will

be able to arrive at a common conjecture that support any particular equilibrium.

The alternative source for a common conjecture is empirical in terms of a focal point.

Here the obvious candidate must come from the history of prior play which, if we are

analyzing a cooperation problem, must correspond to the ex ante point of noncooperation.

This provides a powerful and long-standing common conjecture that is difficult to

surmount. Moreover, their lack of experience in cooperating on the issue makes it less

likely that a natural cooperative focal point will be obvious to the actors. Thus on neither

theoretical nor empirical grounds can the folk theorem provide an adequate account of

getting to cooperation.

In short, the folk theorem tells us which cooperative outcomes are possible, but it tells us

nothing about how cooperation comes about. Indeed, when actors are not cooperating, the

folk theorem probably predicts more of the same. In short, although it is fundamentally

about the importance of play over time in promoting cooperation, the theorem does not

address how actors can change equilibria within the model.19 Instead, the standard use of

the folk theorem is as a big bang theory of cooperation, in which cooperation is predicted

to emerge from nowhere and (hopefully) to settle on some attractive equilibrium on or

near the Pareto frontier. Where there is a pre-existing equilibrium, the equivalent big

bang prediction of direct movement from the status quo to a new, superior equilibrium is

especially unpersuasive. The possibility of cooperation is assumed to result in its

realization — without any explanation of how cooperation comes about, how a single

19

To be sure, a particular supergame equilibrium may include alternation between different

outcomes in the stage game but this is not the same as a change in the supergame equilibrium.

Evolutionary approaches (e.g., Axelrod 1984; Kandori et. al. 1993; Young, 1998) do provide an

account of change over time as the frequency of different types of actors changes – because actors

who follow certain strategies become less numerous, perhaps by learning about better ways to

play the game. This would predict some forms of gradualism (e.g., where successive states

adhere to big bang agreements) but not other types of gradualism considered below. Moreover,

we argue that this type of selection mechanism, even when interpreted more broadly as

“learning,” does not offer an accurate general account of the dynamics of international

gradualism.

11

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

equilibrium is selected and a common conjecture created, and without any account of the

actual history of the process.

The inadequacy of a big bang theory of cooperation is reflected in the actual experience

of international relations, where cooperative arrangements usually emerge in a series of

steps.20 The WTO has developed through a series of complex negotiating rounds over the

past fifty years, as has the European Union over forty; Law of the Sea Conferences have

been multiple and protracted. Major international agreements are often reached through

extensive series of technical meetings, negotiating sessions and diplomatic conferences.

International organizations such as the UN specialized agencies provide on-going sites

and agencies for developing cooperative arrangements. In other cases, negotiations are as

much tacit as explicit – as in the Cold War combination of détente and SALT talks – as

the parties move over time toward a mutually preferred outcome.

In order to apply the power of the folk theorem to real problems, the theorem must be

augmented by an analysis of the process through which actors reach cooperative

outcomes. Such an account should help us understand how actors select among the many

available equilibria, solve their bargaining problems, reduce various forms of uncertainty

and overcome the Assurance problem by developing an appropriately effective common

conjecture. In the next section we begin to develop such an account in terms of an

informal theory of international legalization as a “focal process” that allows states to

gradually overcome the impediments to cooperation identified by the folk theorem.21

II. Gradualism and Legalization as Processes of Cooperation

From Focal Point to Focal Process

Actors who face a multitude of possible outcomes, yet know neither the full range of

possibilities nor even their interests in detail will face serious difficulties in selecting a

focal point around which to establish an equilibrium. In this circumstance, it may be more

effective to agree on a procedure for determining a focal point. Such a focal process

allows actors to discover the feasible outcomes, evaluate these alternatives, bargain over

them and, ultimately, find or create a focal outcome. In domestic society, a wide variety

of focal processes — including collective bargaining, arbitration, legislation,

administrative regulation and litigation — determine outcomes. In international relations,

the rules and practices of diplomacy have historically provided general procedures for

20

Not all international agreements are gradual. Agreements about problems that are wellunderstood, relatively uncontested and relatively small scale might be expected to be “big bang.”

Moreover, crises surrounding major breakdown in the international system (and therefore destroy

preexisting focal points) may also promote big bang agreements. Examples might include

Westphalia, Congress of Vienna, League of Nations, and the United Nations. We postpone the

question of when we will get “big bangs” versus gradualism until we have a better understanding

of the advantages of gradualism.

21

See Roger Myerson Game Theory pp. 372-4 for a discussion of a related concept of focal

negotiation, noting that “developing a formal model of focal negotiation seems to be a very

difficult problem.”

12

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

negotiations, and these remain an important part of the infrastructure international

agreement. More recently, the negotiation of legally binding treaties or the creation of

some variety of “soft law,” have emerged as the principal ways of pursuing international

cooperation. International organizations have also become accepted forums for pursuing

mutual interests in many (but not all) substantive issue areas.

An important aspect of focal processes is that they create opportunities for the emergence

of leadership in organizing a group to move toward a better equilibrium. Individual

states often serve as “lead” states on an issue where they have a special stake and seek to

promote a transition to a better equilibrium. Other states will welcome this leadership

insofar as it promises to benefit them but they also will be wary of leadership that may be

more self-serving than in the common interest. The formal rules and informal norms of

procedure provide ways to both enable and constrain the exercise of leadership.

Leadership can also be created through delegation to a third party, such as an arbitrator or

expert group that is empowered to propose or even determine a solution. International

organizations are sometimes used in this way. Delegation is especially compelling when

the third party has an informational advantage — or can develop one — that allows it to

select a superior outcome for the parties. But acceptance of a third party also depends on

its being seen as neutral and independent.22 Because nation states are reluctant to delegate

significant authority — especially in highly uncertain circumstances or where they worry

that IOs will unduly expand their institutional power —states usually participate fairly

directly in focal processes at the international level. Typically, states further protect their

interests by reserving the right to not ratify agreements or to opt out of rules and

decisions (in contrast to binding domestic procedures like legislation, regulation and

adjudication). Nevertheless, some limited delegation to institutions and experts usually

serves to make information collection and bargaining more efficient.

Civil society groups have recently provided leadership on issues like human rights and

land mines, while business NGOs have long played an influential role in areas of

economic regulation. Since their own resources are limited, civil society efforts often

concentrate on pressuring and persuading IOs and states to take up their causes in

international forums. While states have been wary of many of the newer civil society

actors, they sometimes welcome the significant expertise that NGOs bring to bear on

problems. This can be valuable in promoting cooperation and some international

procedures have been adapted to provide an entry for NGO efforts.

Agreement establishing a new equilibrium is usually not reached in a single step, but

rather develops through a series of smaller agreements. Legalization often provides a

22

Flipping a fair coin or “splitting the difference” are examples of mechanisms for selecting a

focal point when parties know the best outcomes but need an independent and neutral device for

choosing among their differing preferences. In the cases of prime interest here, however, the

problem of equilibrium selection is complicated by a prior informational deficit regarding what

are the best outcomes. Sometimes the resolution of the informational deficit biases the selection

process — as is sometimes alleged by the South when Northern experts propose solutions to

problems of trade or environment. For a discussion of the importance of neutrality and

independence for international organizations see Abbott and Snidal (1998).

13

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

useful way to organize such moves towards cooperation. The legalized arrangements

known as framework conventions are designed to initiate a series of separate substantive

protocols en route to a final outcome, often with states allowed a range of à la carte

choices along the way. Similarly, the intent of many soft law arrangements is that the

parties will gradually tighten the precision and legally binding character of the

undertakings over time, perhaps adding substantive content as well (Abbott and Snidal

2001).

Before examining how legalization operates as a focal process, we discuss the general

advantages of gradualism as a way to develop international cooperation. We focus on the

ways gradual approaches help overcome the impediments to cooperation identified

through the folk theorem.

The Advantages of Gradualism

Gradualism is the division of a problem into smaller steps that can be acted upon

separately over time and ordered in such a way as to facilitate cooperation. Gradualism

refers to breaking cooperation into steps, not necessarily to the speed at which

cooperative outcomes are attained. Gradualism surely will be slower than “big bang”

cooperation when the latter is viable. But gradual processes vary widely in speed and

duration. And even a lengthy gradual process that succeeds is a faster route to

cooperation than a big bang approach that fails. Figure 3 depicts stylized gradual process

towards a cooperative outcome.

________________

Insert Figure3 Here

________________

In a gradual process, steps that are known to have high benefits and low costs can be

sequenced first —increasing the immediate incentives to cooperate. This logic is not

restricted to material considerations; normatively desirable and uncontroversial steps also

can be taken first. Similarly, steps that pose less risk (including distributive uncertainty)

can be sequenced before those that pose greater risks (including delegation to

international institutions). Membership can also be sequenced. States that will derive the

greatest benefit and can be relied on to participate and comply with the agreement can be

included first. States that do not see the benefits of cooperation can be excluded initially,

while states that lack the capacity to cooperate can be granted an affiliated status and

given technical assistance to prepare them for full membership later.

Of course, both the separation and the ordering of steps and members are subject to

technological and political constraints. Some steps cannot be separated or taken in any

sequence. Some affected parties cannot be isolated from the group, as with public goods

and externalities. Finally, political considerations make it hard to put some steps ahead

of others, while preexisting institutions may determine the membership groups available

for addressing specific problems.

14

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

Gradualism also replaces the uncertainty of a “leap in the dark” with opportunities for

learning through successive small steps. This learning can address the various forms of

uncertainty that undermine cooperation in the folk theorem. It can reduce technological

uncertainty about the issue, uncertainty about the preferences and capacities of others,

and uncertainty about oneself (including one’s domestic politics) that make it difficult to

know the set of cooperative possibilities. Deliberation and persuasion in the course of a

focal process also facilitate normative learning, important where accepted values and

beliefs must be rethought in the light of emerging problems or information. Furthermore,

the focal process provides a means to develop the common expectations necessary to

support a cooperative equilibrium. All these effects contribute to a mitigation of the

Assurance problem.

A key advantage of taking easier steps first is that it enables learning processes that

facilitate subsequent cooperation on more difficult steps — and may also identify steps

that are too costly or not desirable. By providing valuable information on the likely

benefits and costs of future steps, first steps reduce technological uncertainty. Early steps

also can be chosen because they provide the most information. Often, initial steps are not

substantive undertakings at all, but simply procedures for gathering, sharing and

enhancing the reliability of information. Agreements frequently include procedures to

evaluate the impact of early steps in order to improve understanding of possible future

steps. And potential members may be convinced to join the effort as they observe the

benefits of cooperation realized by the initiating group and learn about the technical

aspects of implementing an agreement.23

Early steps provide a means to determine whether other states can be counted on to

cooperate and to facilitate confidence-building through transparency and interaction

among governmental and societal actors. Cooperation on first steps makes commitments

to cooperate on future steps more believable; states that are unwilling or unable to

cooperate on easy steps can be excluded (or at least not counted on) for further steps.

Moreover, political reactions to early steps inside other states — especially the intensity

of preferences and interplay of domestic supporters and opponents — provide valuable

information regarding their political ability to carry through on subsequent steps.

Revelation of domestic political configurations in other states also enables transgovernmental and trans-societal strategies to rally supporters and respond to the

objections of opponents there, with the aim of modifying national preferences.24 States

whose capacity or interest in cooperation is initially in doubt can demonstrate their ability

and sincerity through participating in early steps.

23

States may also learn that cooperation is a bad idea — in which case small steps provide a

cheap lesson. Although we focus on the case where cooperation is beneficial, learning when not

to cooperate is equally valuable.

24

Of course, the same is true for opponents. Our use of the term "cooperation" implies that some

alternative is socially preferred "on net." One justification for this is that of efficiency

maximization (Becker, 1975) whereby the gainers are able to outweigh or compensate the losers

on the issue. A different (but not opposed) justification is that one normative position is more

compelling than another.

15

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

Gradual cooperation also provides an opportunity for actors to learn and even modify

their own preferences. States can gauge domestic reactions to small initial steps with less

political risk than from larger steps. These early stages of cooperation further provide an

opportunity to mobilize domestic coalitions in favor of further steps, to assuage potential

resistors or encourage them gradually to adjust their investments and activities in the

desired direction, and to enhance domestic capacities to implement cooperative measures.

Insofar as initial steps cause domestic opponents to change their behavior and invest in

new practices — for example, as firms become more export-oriented or adopt

international codes of conduct — these groups may even become supporters of further

cooperation. Normative learning can be an important aspect of this process, as domestic

actors are mobilized around values such as human rights or biological diversity that they

had not previously taken into account.

As these examples make clear, the potential for learning in gradualism goes beyond

simply resolving uncertainty about existing technologies and preferences to the

possibility of changing them, or finding the “right” technologies and preferences. In

terms of technology, early stages of international processes are often oriented towards

discovering the nature of a problem (e.g., Is there global warming and what will be its

consequences?) and developing feasible solutions (e.g., Will tradable emission rights help

address the problem?), especially in technical areas like environmental regulation. In

terms of preferences, early stages of cooperation are typically oriented towards

reconciling divergent preferences, often as governments and societal actors try to

persuade others, at home and abroad, of the importance of certain collective goals. Arms

control, trade liberalization, human rights and environmental protection are all areas

where much of the work of international negotiations has occurred at this prior level of

deliberation, aimed at understanding problems and technologies and accepting common

goals. Indeed, cooperation cannot proceed until states agree to some extent on the nature

of the problem and on what constitutes desirable or appropriate behavior.

The most important learning that occurs through a gradual process is with respect to the

evolving “focal point” for cooperation. Each step in the process potentially serves as an

interim focal point for action. As states see each other abiding by successive gradual

steps, the process itself becomes focal, generating common expectations for the behavior

of participating states. Public acceptance of agreement terms, together with actions and

pronouncements in associated forums and investments around successive steps by

governments and private actors, serve as hostages that reinforce each step and allow

states to update their expectations in a coordinated fashion as cooperation proceeds.

Insofar as the process and the intermediate agreements are seen as legitimate, these

expectations will be reinforced by the normative expectation that states should implement

an equilibrium to which they have agreed. These intermediate agreements also narrow

down the set of acceptable ultimate agreements as states move along the path to

cooperation (Figure 3).

Equally important, a successful gradual process progressively diminishes the original

noncooperative status quo as a compelling focal point. By demonstrating cooperation at

even a low level, states diminish expectations that the outcome must revert back to the

noncooperation point. Even if states are unable to proceed forward, none has an

incentive to go back. This potentially produces a “ratchet” effect, where each successive

16

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

level of cooperation provides a mutually agreeable focal point for an equilibrium that is

stable against downward moves while remaining open to further upward gains Although

limited or incomplete, each step can be structured substantively and institutionally to

function as a cooperation equilibrium, recognizing that the dynamic process may be

halted at any time. Downward stability is enhanced by the investments and pledges of

reputation that actors make around the agreement, while upward mobility is enhanced by

institutional arrangements developed as part of the focal process.

Gradualism is no panacea. Groups that oppose cooperation will use gradualism as a way

to organize opposition and to put off taking substantive action by substituting talk and

study for concrete steps. Even if opposition is not a problem, distributive problems

remain and bargaining will be intense. In selecting a focal process and in evaluating each

of the steps it produces, states and other concerned actors will be attentive to how even

early steps establish an overall direction to the negotiations and narrow the set of

potential ultimate equilibria. Thus the choice of a focal process will not be neutral but

contested — as indicated by past differences over locating specific issues in UNCTAD

versus GATT or in WIPO versus WTO. However, because the process can be sequenced

so that early steps emphasize efficiency gains over distributive issues, gradualism has

important advantages.

Most importantly, the combination of gradual, ordered steps with learning, confidencebuilding and adjustment significantly ameliorates the Assurance problem. Small steps

mean that states risk no major catastrophe should others fail to cooperate in the early

stages. Moreover, if a step turns out to be unfavorable to one or more parties, adjusting

the terms of cooperation in subsequent steps can provide a remedy. The normative

attractiveness and/or favorable benefit/cost ratio of initial steps further increase the

incentives to cooperate (and decrease the incentives to cheat) at the early stages where

states have their greatest doubts. The more difficult and riskier stages of cooperation are

postponed until they can be supported by the confidence established through successful

experience in cooperation. Above all, success in the early stages of cooperation and

the investments that states and domestic actors make around the process and in learning

about its benefits increase mutual confidence that others are truly engaged in the

cooperative process and will abide by the evolving terms of agreement.

Legalization as a Focal Process

Legalization is only one category of focal process, but it has properties that make it a

mainstay of international cooperation. First, legalization is easily adaptable to a strategy

of gradualism. Legal and quasi-legal arrangements are composed of distinct (though

interrelated) elements: the nature and force of the obligations imposed; the precision of

those obligations; and the delegation of authority to interpret, apply and supplement

them. Thus actors can determine at the outset whether to seek a “big bang,” moving

directly to commitments that are highly legalized as well as substantively deep and

17

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

widely accepted, or to separate the elements of legalization and develop them in stages

over time. 25

If the choice is made to proceed in steps, actors can order the elements of legalization,

choosing which to adopt at the outset and which to add or strengthen subsequently. For

example, if the actors choose to begin with a framework convention, they accept binding

legal obligations but limited substantive commitments; they may take on additional

commitments in later protocols. In a soft law approach, in contrast, the actors may begin

with fairly detailed normative commitments but no legal obligation; they may then

strengthen their obligation over time, as by adopting a treaty to replace a soft declaration

(Abbott & Snidal 2002). Because such choices are generally available, proponents and

opponents of cooperation actively assess the individual elements of legalization and

debate the order and rate at which to create them.

Second, legalization helps ensure that new arrangements will mesh with prevailing norms

and institutions. International law is the standard format and language for serious

international commitments, and is thus often the ultimate objective for successful efforts

at cooperation (see Abbott et al., 2001; Abbott & Snidal, 2001). A legalized process

provides an effective way to move toward such an endpoint. In turn, the likelihood of a

legal outcome shapes the process of legalization. Scholars have identified a variety of

characteristics that determine whether rules and norms are regarded as legitimate and

deserving of obedience (Fuller, 1964; Franck, 1990). Successful legalization will build

these traits in as the process proceeds.

Both interim and final equilibria will be more successful if they are integrated with

surrounding norms, agreements and institutions. Legalization facilitates this kind of fit.

Similarly, agreements and other actions can be found to have legal effects under the

general international system even if they were not thought to be legally binding when

adopted. For example, normative declarations can contribute to the emergence of

customary law and serve as the basis for authoritative decisions by courts and other

institutions. Legalization allows actors to anticipate and prepare for such possibilities.

International agreements must also mesh with national legal systems. Most international

undertakings require internal implementation by states to be effective. In some cases,

national legal rules constitute the problem that international cooperation is designed to

address. In other cases, domestic institutions may base authoritative decisions on

international instruments. And opponents of international cooperation frequently cite

domestic legal issues as reasons not to act. A legalized process helps produce agreements,

both interim and final, that respond to these demands. The need to mesh with domestic

25

It is important to note that all cooperative processes are in some sense “legal,” because all take

place within a general international legal system that, for example, recognizes certain actors as

legitimate participants, sets fundamental rules regarding diplomacy and the nature of international

agreements, and provides other important background rules, such as the obligation to settle

disputes by peaceful means and the rule of pacta sunt servanda, states must observe their

agreements. In addition, international law shapes the constitutions of international organizations

that serve as forums for negotiation and the centers of gravity of international regimes.

18

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

legal systems also shapes the process of legalization: actors must study the diverse

requirements of national systems and prepare agreements that accommodate them.

Third, legalization has practical benefits as a gradual strategy. Legalization offers an

established and generally applicable set of procedures that reduces the transactions costs

of negotiation, quite apart from the advantages of a legal agreement. Legalization

connects specific negotiations to broader institutional arrangements, and offers general

ways to handle classes of problems. Although imperfect in this regard, legalization offers

a relatively neutral set of arrangements for striking international bargains. At the same

time, legalization is highly flexible, easily adapted to particular issues — as in the design

of soft law processes. These advantages are amplified when the process is conducted in

an established institutional framework, such as an international organization.

Fourth, legalization facilitates the kinds of learning that are among the main advantages

of a gradualist strategy. Because legal undertakings – and to a lesser extent soft

arrangements that may lead to legal undertakings – require states to stake their general

reputations as law-respecting actors in international society, legalization provides an

effective screening device to reveal whether others are sincere about cooperation. Since

international law is the accepted language for significant commitments, refusing to use

that language, or at least quasi-legal normative language, suggests powerfully that one

cannot be counted on for cooperation.

Gradual legalization also helps states reveal and shape their own preferences. Processes

of norm development can be highly effective at activating supporters and opponents of

cooperation. Governments can mobilize latent supporters in the general public around

soft undertakings without incurring the political risks of firm commitments. Soft

undertakings also signal to domestic opponents the likely direction of policy

development, enabling them to adjust to the new reality over time, at a lower cost.

Normative deliberation and the development of legal rules also help participants learn

about the evolving focal point for cooperation and form a common conjecture.

Finally, legalization helps support the gradual “ratcheting-up” of cooperation. The

normative power of legal and quasi-legal commitments, their link to the broader legal

system and the pledges of reputation they entail all help even interim agreements

influence behavior in desired directions. The same characteristics, plus the ability of

supporters to invoke even quasi-legal commitments politically as standards of behavior,

provide stability against backsliding. At the same time, by reducing transactions costs,

legalization facilitates further movement toward enhanced cooperation.

To be effective in addressing a particular issue, of course, the process of legalization must

be more tightly specified. This is often done through the choice of a forum (e.g., WTO

vs. ILO) and a procedure within that forum (e.g., treaty negotiation vs. conference

declaration), and through prior agreement on the scope and objectives of the negotiation.

Ideally a legal process should be matched to the nature of the issue and the actors

involved. For example, an IO whose members share an interest in and capacity for

cooperation on an issue will be a more effective forum than one whose membership

includes strong opponents or likely laggards. Similarly, the process should be matched to

the expertise and competencies of the forum. Some IO’s may excel at certain types of

19

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

information production, while others may offer a superior setting for bargaining or

normative deliberation. An IO might even be “too competent” in certain respects, making

states reluctant to initiate a cooperative process for fear of being prematurely enmeshed,

or out of concern that their need to move slowly will undermine the organization (Abbott

& Snidal, 2002).

But the choice and specification of a process is not politically neutral. This is well

illustrated by the tendency of states and other actors to engage in “forum-shopping,”

seeking venues likely to produce desired outcomes. The choice among forums and

processes is likely to be contested, with the equilibrium selection problem reproduced as

an institutional selection problem.26 This problem will be simplified to the extent that the

menu of institutions and procedures capable of handling a problem is limited to a few

alternatives. More importantly, the problem may be attenuated insofar as the available

procedures limit the distributive range of potential outcomes. Gradualism helps to

accomplish this goal, as it allows actors to ensure that their interests and values are being

adequately accommodated before fully committing to an agreement.

In summary, the folk theorem shows that cooperation in international affairs may be

supported by the decentralized enforcement but says little about how we get to a new

cooperative equilibrium. Actual movement towards cooperation often require a gradual

process to addresses various factors that limit the applicability of the folk theorem.

Gradualism allows states to pursue cooperation in steps that make it easier and that

engage various types of learning — about the problem, about each other, about

themselves and about their joint cooperative equilibrium — that are essential to resolve

the Assurance problem. Finally, legalization has a set of properties that make it an

effective focal process and may explain why it is so widely used in international affairs.

The next section examines how a legal focal process works in practice.

II. The OECD Anti-Bribery Convention: Gradual Legalization as a Focal Process

In 1977, responding to revelations of foreign payoffs and corporate slush funds, the US

enacted the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), making it a crime for US firms to

bribe foreign government officials in order to obtain business. No other government

followed suit. The US sought international agreement on foreign bribery rules bilaterally

and in the UN and OECD, but these efforts came to naught. A decade later the US was

again rebuffed at the OECD.

In the early 1990s, however, the US succeeded in initiating a process of gradual

cooperation in the OECD. Led by political entrepreneurs in government, the OECD and

civil society, this process led member governments, over several years, to accept a series

26

See Riker (1980) for a discussion of how preferences over institutions depend on preferences

over the outcomes that they are expected to generate. This builds off the structure induced

equilibrium literature, which shows how institutional arrangements determine outcomes where

(voting) cycles might otherwise occur. Although we do not consider the problem of cycles here,

our underlying logic of institutional rules is similar with respect to the narrowing down of the

available outcomes found through the folk theorem.

20

Folk Theorem

Abbott & Snidal

of increasingly broad, substantive and detailed undertakings on bribery in the form of

non-legally-binding Recommendations. In December 1997, the process culminated in the

legally binding Anti-Bribery Convention requiring member governments to adopt

domestic legislation making it illegal for their multinational firms to bribe foreign public

officials. It further created an oversight arrangement through an OECD Working Group

to scrutinize proposed domestic legislation and monitor its implementation and

effectiveness.

This section of the paper explores the empirical puzzle of why the US was unable to

promote a cooperative agreement in earlier efforts but then was fully successful in the

OECD?27 We show how the use of gradualism through a legalized OECD process

enabled states to reach a cooperative outcome through a series of steps over a relatively

short time period. The section begins by outlining the political structure of the issue and

then presents the OECD process chronologically, analyzing each stage in light of the

theory of process presented earlier.

The method of this section is similar to that of the “analytic narrative” (Bates et. al, 1998)

which can itself be viewed as a theoretically refined version of process tracing (George).

Analytic narratives use a systematic deductive structure — in this case rational

cooperation theory — as a guide to interpreting and understanding historical

chronologies.28 Such narratives do not provide tight tests of the theory but rather use the

theory to constrain the allowable interpretations of the case. Here we take the approach

one step further by using the empirical account to illuminate the deficiencies of purely

structural theories of cooperation, as outlined in our account of the limitations of the folk

theorem. Thus our joint purpose is to understand how states achieved international

cooperation to combat transnational bribery and, more generally, to illuminate how

attention to legal and other processes can improve our theoretical understanding of the

transition to cooperation.

Structure of the Issue

The cooperation problem in international bribery can be viewed first from the perspective

of multinational firms competing for a contract to be decided by a foreign government

official who can be bribed. This has been a common situation for large construction and

aeronautical contracts, especially in the developing world. It places firms in a Prisoners’

Dilemma situation where each has an incentive to pay a bribe to be considered for the

contract, but all would be better off if all refrained (or were prevented) from bribing. The

home states of these firms are in a similar PD relation since if they unilaterally restricting

bribery will lead to a loss of exports and home country jobs, but states would be

collectively better off with effective international limitations. Unfortunately, the inherent

27

Our analysis is based primarily on interviews with twenty-eight of the key participants in the

development of the OECD Convention and related international arrangements, as well as archival

files and secondary sources. The interviews are listed in Abbott and Snidal 2002b.

28