Charity Begins at Home

Corporations should stick to earning profits, so their

owners have wealth to give away

By THOMAS G. DONLAN

Sign of Hope

If it's more blessed to give than to receive, what should we say

about the charitable gifts of corporations? Although many

corporations claim to have cultures, values and philosophies, few

if any claim to have souls. Since being blessed is not the same as

receiving a return on investment, a blessing is worthless to a

corporation.

And "soulless," indeed, is a word frequently used to describe

corporations in the rhetoric of those who would like to make the

world a better place.

Yet American corporations distribute about $9 billion a year with

roughly the same intent, sometimes to the same people. Although

corporations make their gifts without hoping for the blessing of

grace, they almost always give while making sure that a Higher

Authority is watching. That Power, however, is the United States

Internal Revenue Service.

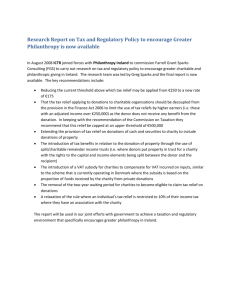

The government ignores a limited amount of corporate income

when it's given to charitable institutions. It seems simple justice to

deduct from taxable income such sums that the earner does not

keep or use for his own purposes. Also, the deduction is intended

to increase the sums people grant to charities.

But these reasons apply better to private donations than to

corporate charity. And with three-quarters of a million

philanthropic institutions in the U.S. receiving private donations

totaling more than $140 billion a year from individuals, we can

afford to question the wisdom of the corporate charity deduction.

A Matter of Property

Corporate contributions to charity are wrong, for the same

reasons that forced political contributions from employees and

union members are wrong. Corporate wealth does not belong to

management, it belongs to shareholders. Choosing a charity or a

candidate is a personal action, and a soulless group such as a

corporation or union should not take that choice away from its

owners or members.

Many companies that say they do understand whose money it is

still do not shy from making large charity donations -- they just file

them under advertising and promotion, and brag about them

under the heading "strategic philanthropy." Charities are noticing

that their corporate donors are more aggressive about splattering

their names on anything the cause has in public view, and vice

versa, putting the charity's name on corporate ads as a sort of

endorsement. It makes no difference that toiletries have nothing

to do with endangered species. Everybody likes animals and

maybe the toiletry company can use that to help people like their

products. So a toiletry company might pay to put the World

Wildlife Fund in its ads.

(Defending corporate interests also seems to require strategic

philanthropy. Beleaguered pharmaceutical companies scramble

to figure out ways to give drugs to African AIDS victims rather

than be labeled soulless killers for wanting to concentrate on

selling their products at higher prices in rich nations.)

But such expenditures do not need to be counted as charity. If

they are wise uses of the shareholders' money, then they will be

tax deductible as ordinary business expenses.

Charity is something different; it's an expenditure on which the

giver expects no real return. And that's what a corporation should

never do intentionally.

Empowerment for Extortion

Tax deductions for charitable contributions also empower

extortion rackets like the Wall Street Project, run by the Rev.

Jesse Jackson. In recent weeks, enterprising newspapers have

reported that his Citizenship Education Fund and its affiliates on

Wall Street, LaSalle Street and in Silicon Valley have taken large

contributions from corporations they criticized, then went silent on

opposition to hiring and merger plans they had opposed.

Sounding like a U.S. Senator defending campaign contributions,

Jackson last week told one newspaper that "The same people

that you challenge one day, once they come around and honor

the law, then we build relationships with them. Of course that's

what we do. It is legal, appropriate and effective." He added, with

the sonorous wisdom of a Godfather, "Those who benefit,

contribute."

The difference between this operation and a protection racket lies

mainly in the style of the threat. Instead of receiving visits from

leg-breakers, those who defy Jackson's shakedown operation are

punished by the sight of their corporate headquarters on the

evening news, surrounded by angry demonstrators who charge

that the company is the embodiment of evil.

Jackson, of course, wishes to advance the fortunes of minorities,

a worthy goal and one for which the tactics of demonstrating

public indignation were honed in the days of the civil rights

struggle in the 'Sixties and 'Seventies. The Wall Street Project, he

has said, is "a matured version" of Operation Breadbasket, which

he ran in Chicago 30 years ago to open jobs to blacks.

But the tactics applied successfully to governments and small

businesses for the benefit of needy individuals are too easily

perverted when they are applied to large corporations -- as with

the fortunes of Jackson, his family and his friends.

For example, Jackson put Anheuser-Busch into his spotlight a few

years ago, noting with appropriate disdain that there were no

African-American distributors of Budweiser beer. Thanks to his

efforts, there now are several African-Americans enjoying the

regional monopolies that the company has created. Unfortunately

for Jackson's reputation as an idealist, two of his sons received a

lucrative distributorship in Chicago, though they lacked previous

experience in the beer business.

The Citizenship Education Fund and other affiliated groups

opposed the merger of Ameritech and SBC Communications

(claiming it was detrimental to low-income customers), until a

Jackson friend's investment partnership was invited to join a

group buying part of Ameritech's mobile phone franchise. SBC

also became one of the largest contributors to Jackson

organizations.

Such gifts are not always tax deductible, and even without a tax

break corporations are likely to conclude that danegeld is cheaper

than war. But the tax deduction for corporate contributions puts

the government on the side of extortionists when it should at least

be neutral.

The Bush administration, unfortunately, is headed in the wrong

direction. The new budget proposes raising the limit on

deductions for corporate contributions.

The best way for corporations to give to charity is to pay profits to

their owners and employees. And the best way for the

government to encourage corporate philanthropy is to eliminate

the corporate deduction while permitting deductions for dividends

and bonuses that recipients use for their own charitable purposes.

Failing such legislative reform, there's a substitute mechanism for

corporate giving that is simple and already widely used.

Corporations that wish to make altruistic donations from earnings

should not make their own choices. They should match the

private donations of employees and shareholders. Such a policy

would be more blessed than direct gifts.

Sign of Hope

California makes progress by raising electric rates

Several weeks ago, California Gov. Gray Davis declared that he

could solve his state's electricity crisis in a matter of minutes if he

were willing to let rates rise. Although we had previously

considered the governor to be an "economic idiot," it now

appeared that he was more obstinate than stupid. That was a real

improvement, for stubborn people occasionally change their

minds, while idiots generally have very little of a mind to change.

Last week, the governor did not exactly change his mind, but at

least he started using it a little. He did not oppose the California

Public Utilities Commission's approval of a rate increase and

hinted that he might endorse it eventually. Even better, the rate

increase was designed for conservation, by letting the highest

rates fall on those who use the most electricity.

Not everyone appreciates the rate increase, however. "This is like

giving crack to an addict," said Harvey Rosenfield, president of

the Foundation for Taxpayer and Consumer Rights in the

People's Republic of Santa Monica. He meant that raising rates

would stimulate out-of-state power generators to gouge more of

the people's money, but he had it exactly backward: California

politicians have been pushing cheap electricity, and higher prices

should reduce demand for the drug.

Editorial Page Editor Thomas G. Donlan receives e-mail at

tg.donlan@barrons.com

Return to top of page | Format for printing

Copyright © 2001 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright and reprint information.